On 1 July 1912, a Ukrainian mourning demonstration took place in Lviv, organized in memory of Adam Kotsko, a Ukrainian student at Lviv University killed during Ukrainian-Polish student clashes two years earlier. This event is a rare example of Ukrainian national demonstrations in Lviv in the early 20th century that turned into a conflict with the police. Ukrainians in Lviv mostly held their events in prearranged locations; if they tried to do something "off-plan" (as during the commemoration of the anniversary of the siege of Lviv by Khmelnytsky), the police's reaction was immediate and harsh. The Poles, as the experience of 1905 or the demonstrations over the Kholm/Chełm Land showed, often clashed with law enforcement agencies.

It is important to note that the Ukrainians held the rally against the backdrop of another deterioration in Ukrainian-Polish relations: a month earlier, Lviv celebrated the 250th anniversary of Jan Kazimierz University. This anniversary was an element in the struggle for the university in Lviv — as an argument against the opening of a Ukrainian university or the "Ukrainization" of the existing one. A month and a half before the Ukrainian demonstration, Lviv also saw riots and clashes between Polish youth and the police over the separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land from the Kingdom of Poland. This background was not conducive to mutual understanding and a peaceful course of any Ukrainian events.

The main idea — to show that Lviv is "from time immemorial / originally" Ukrainian, as regularly reported in the Ukrainian press — remained unchanged. However, the course of the event — with a march to the city center, with speeches from the balcony of the Prosvita Society building despite opposition from the police and Polish nationalists — was unusual for Ukrainian demonstrations. Actually, Ukrainians adopted the Polish experience of street politics, using all the techniques that Polish activists had previously used in Lviv, in particular in 1905 or during the riots near the Russian and German consulates. The 1912 demonstration can be considered a truly modern political action when Ukrainians "went beyond" the boundaries of their societies or "allocated" areas and dared not only to confront the police but also to continue the rally afterward.

The day before: blackmail with blood on the streets

The level of tension in relations between the Ukrainians and Poles can be revealed by the following episode: the Polish press reported that Ukrainians were allegedly preparing an assembly and a demonstration in mid-May, just before the Polish anniversary of the Jan Kazimierz University, and called on the police to ban the Ukrainian events. The police responded by saying that no Ukrainian demonstrations were planned, so there was nothing to ban. The Ukrainian event was supposed to be dedicated to the anniversary of the corvée labour abolition.

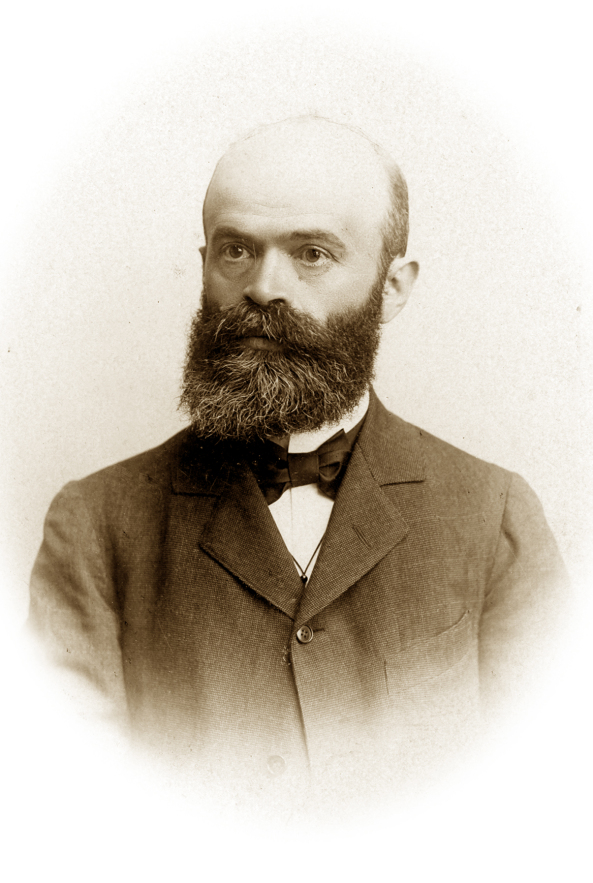

The Ukrainian newspaper Dilo published a front-page polemical article on this issue. It stated, in a somewhat veiled way, that clashes between the Ukrainians and Poles in Lviv would necessarily lead to a similar conflict in the province, where, as it was known, the Poles did not always have a numerical advantage. Therefore, it was not appropriate for the president of Lviv to host delegations demanding that Ukrainian citizens be banned from expressing their position on the street, because other citizens, the Poles, threatened them with violence. In general, the Dilo said, Ukrainians supported peace and mutual understanding, but no one was going to "turn the other cheek" when it came to national affairs. Later, a Ukrainian delegation led by Yevhen Olesnytskyi, a member of parliament, even had a conversation with the governor about this.

Although the police commissioner informed both the president of Lviv and "numerous interested parties" that there would be no actions by Ukrainians, the Polish press continued to call for the "defence of Lviv's Polishness" and threatened "bloodshed in the streets if the authorities did not ban the Ruthenian assembly." Polish youth, influenced by these rumours and publications, decided to "be on the alert" on 16 May. Having failed to find any Ukrainians who would rally on that day, Polish students themselves organized a march through the city in the evening.

Assembly in the People's House

On 30 June 1912, as Ukrainians were not allowed to hold events in the streets, an assembly "on the establishment of a Ukrainian university" was held in the People's House. According to Ukrainian press reports, about 3000 people attended, in particular, representatives of various Ukrainian political environments: Volodymyr Bachynskyi, Volodymyr Okhrymovych, Mykhailo Pavlyk, Yulian Bachynskyi, Yaroslav Veselovskyi, Lev Bachynskyi, Mykola Hankevych, Kost Levytskyi and others. They talked about the Emperor Franz University of Lviv and the struggle for the Ukrainian university as an example of the struggle for national rights in general. They also talked about the importance of the university for the whole of "united Ukraine" and about the importance of Lviv for the cause of "liberating the whole of Ukraine from the Carpathians to the Don", mentioning Adam Kotsko, a student, who was killed two years before, and the students convicted after the riots. In the end, as the march through the city was banned, the participants were invited to the unveiling of a monument to Adam Kotsko at the Lychakiv Cemetery. Even after that, some people did not leave ul. Teatralna for a long time, but there were no conflicts with the police.

The course of the event: a march, clashes, a speech from the balcony

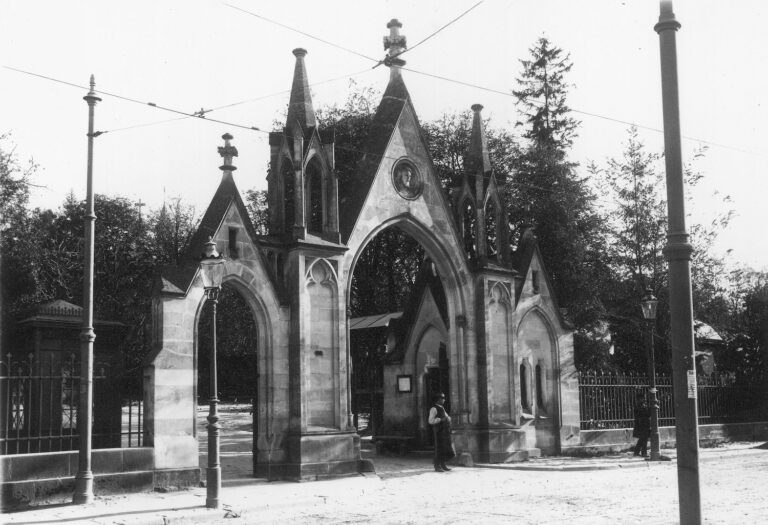

On 1 July, in the evening, a mourning service was held at the grave of Adam Kotsko at the Lychakiv Cemetery. On the second anniversary of his death, a monument was erected there with the eloquent inscription "He died at the university." According to the government-run newspaper Gazeta Lwowska, about 600 people gathered. This is quite a lot, given that the same newspaper estimated the number of Polish demonstrators during the "Kholm/Chełm Land riots" at 1000 people.

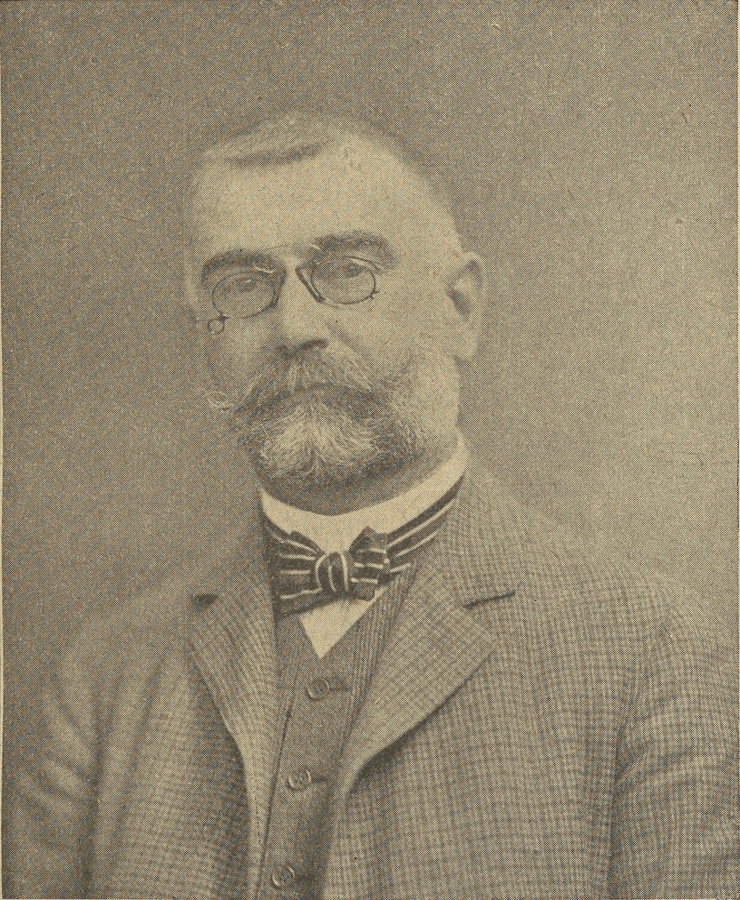

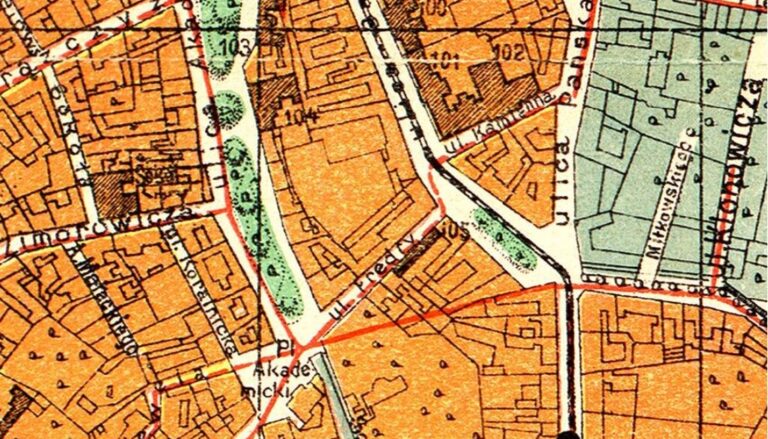

After the speeches were delivered, the participants of the event, singing songs, marched down ul. Piekarska towards the city center. At the beginning of ul. Piekarska (i.e. in the area of its current intersection with vul. Ivana Franka), the demonstrators were blocked by the police. Therefore, some people dispersed, while others managed to reach the Rynok Square in small groups, where they gathered again near the Prosvita building. Here, the editor of the Dilo newspaper, Yaroslav Veselovsky, spoke to them from the balcony about the Ukrainian university case. In the end, he, like the police officers present, called on people to disperse. That was the end of the rally near Prosvita.

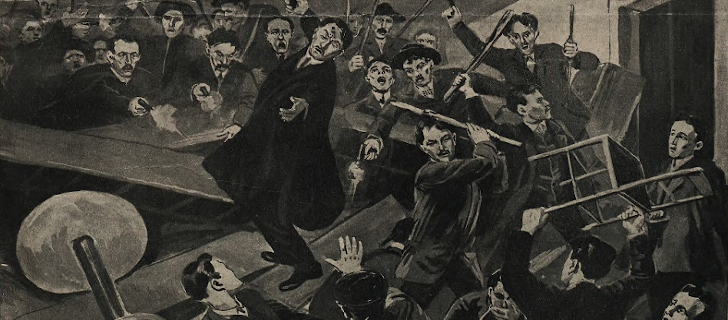

Half an hour later, however, about 100 Ukrainian students gathered near the university, where they started a new rally. Seeing that a police detachment had already arrived and was approaching, the students moved to ul. Akademicka. Polish students came out of the University and the Polish Academic House to meet them, and after a short verbal confrontation, a fight broke out and stones were thrown. It did not escalate to anything more serious, as the police managed to separate the two groups of students. Then the Polish students went to the University, where they sang several patriotic songs (here an analogy with the "battlefield", which seems to have remained under control of one of the "armies", is suggested). The Ukrainians walked down ul. Fredra to ul. Batorego. Only then did the police manage to calm them down and force them to disperse.

A version of the events, somewhat different from that presented by the Ukrainian Dilo and the government-run Gazeta Lwowska, whose information was not fundamentally different, can be found in the Polish democratic periodical Kurjer Lwowski. Firstly, the police allegedly used a common but ineffective method of dealing with demonstrators and ordered them to disperse. Apparently, the demonstrators dispersed from ul. Piekarska only to gather elsewhere — on the Rynok Square. Secondly, the University was already closed in the evening, so the Ukrainians did not run away from the police, but simply turned around in front of the closed doors. The Polish students, accordingly, came out only of the Academic House, and it was only when the fight near the Chamber of Commerce on ul. Akademicka was in full swing that the police appeared.

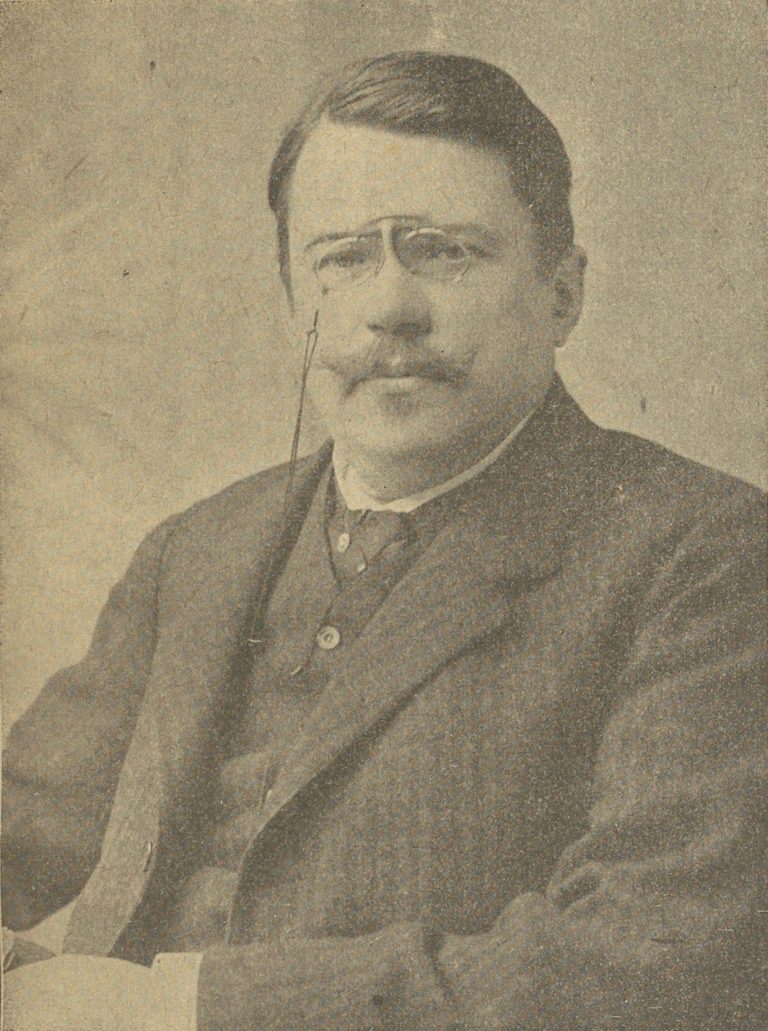

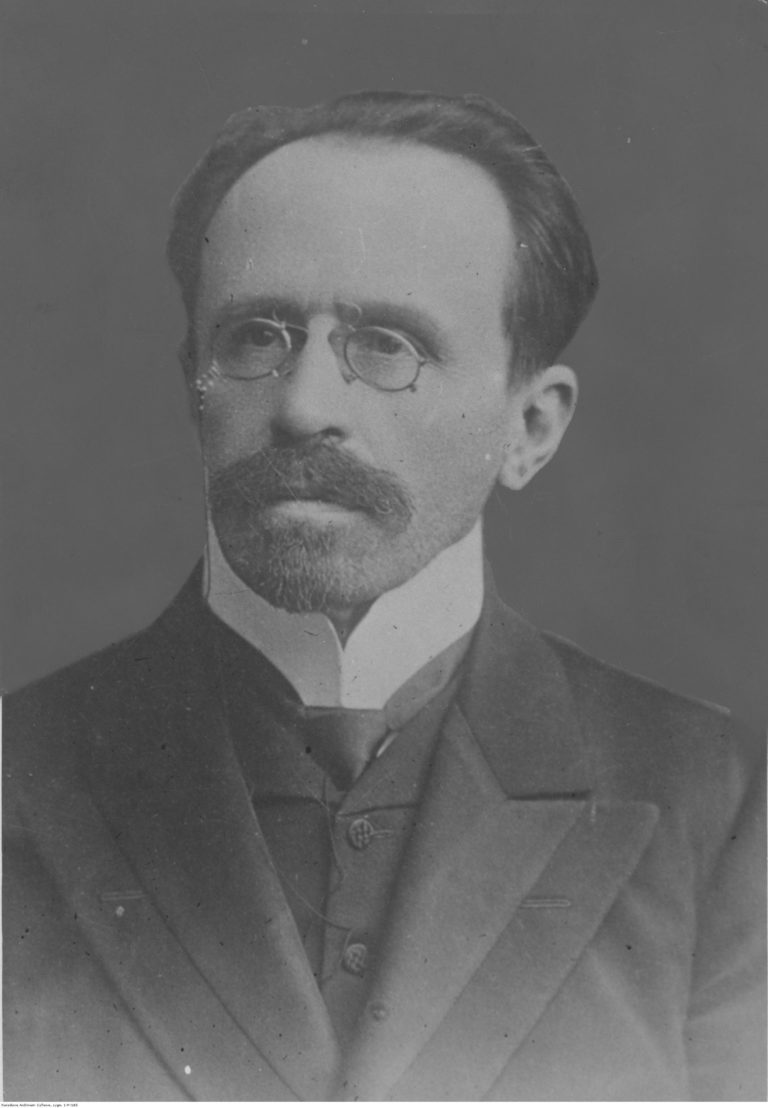

Another interesting detail in this description is that, after the fight with the Ukrainians, the Polish students allegedly tried to break through the police cordon to the University. They suspected that there were more Ukrainians hiding somewhere. It was only when the rector, Ludwik Finkel, came out to them and promised that the University would always be Polish that the students dispersed, singing the "Hymn of the Legions" in the end.

On 1 July, the province held events in memory of Adam Kotsko too. These were mainly memorial services in local Greek Catholic churches, and the press also reported on the laying of flowers at the symbolic grave "made by school children." The general mood of the time was summed up during one sermon with the following phrase: "Our child is being taken out of the school supported by our taxes, with a bullet in his head."

Epilogue

The Ukrainian press wrote that the peaceful demonstration of Ukrainian students, who had merely decided to sing the national anthem in front of the university, was spoilt by aggressive Poles, the police watching inertly the beating of the unarmed Ukrainians. However, and this is the key difference from the Polish press, the Ukrainian press accused the Ukrainian students of recklessness and arbitrariness. After all, according to senior politicians, the march to the university was not necessary for the national cause and was not approved by the "leadership." Therefore, it was allegedly used by provocateurs. This shows that the Ukrainian political elite was not only unprepared for the new challenges posed by the street confrontations but also perceived the students' activity as a threat to its status as the "national leadership."