A developed literature was essential to the national project in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It indicated a kind of completeness of the people and legitimized their right to exist. Writers and poets who shaped literature were considered national prophets who "spoke with the voice of the people," honored as saints, bearers of truth, and seers of the future. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Ukrainians in Galicia fought for the "rights of their mother tongue". Of course, the defense of these rights required a literature in addition to the language.

As in the case of the Polish poet-prophets, the Ukrainians in the late 19th and early 20th centuries began to actively form their "national pantheon". And as with the Poles, there was a conflict in the Ukrainian environment between the secular intelligentsia and the Catholic Church.

There were also significant differences from the Polish situation, such as the starting points or their influence on the authorities (e.g. in the naming of streets in honor of Polish poets). The Greek Catholic clergy was more actively involved in political life and had a greater influence on it, so that the process of society's perception of "national saints" was often determined first and foremost by priests. Another important nuance was that Ukrainian "prophets" did not always belong to the Catholic Church. For example, the most important one, Taras Shevchenko, was Orthodox. His poetry is often anti-clerical, anti-Catholic, and far from the principles of forgiveness and understanding. However, this did not prevent Galician Ukrainians (Greek Catholics) from celebrating his birth since the 1860s.

Poles were apparently unsparing in their negative epithets for this practice. "Dull poetry about haidamaks, priests and Jesuits, as well as revenge on the Lyakhs (Poles)", in their opinion, had a negative influence on Ukrainian youth and made them incapable of dialogue. Even the tragic events at Lviv University were explained by the Polish press as influenced by Shevchenko's works. Polish magazines treated the poem Maria as an outright blasphemy. In the end, it did not take long for the conclusion to be drawn that reading Kobzar turned Ruthenians into anarcho-socialists who murdered governors.

The perception of the Shevchenko cult was also problematic in the Ruthenian camp itself. Russophiles accused Ukrainophiles of spreading the cult of the "blasphemer Shevchenko". The clergy tried to criticize Shevchenko's interpreters and popularizers rather than the "prophet" himself, avoiding complicated issues such as the poems of Maria or Jan Hus. The radicals had it easiest: they glorified Shevchenko and criticized the church hierarchy for imposing censorship.

The Ukrainians, like the Poles, deliberately ignored the existing state borders, which they considered unjust, in building their "national pantheon. Ivan Kotliarevskyi, Taras Shevchenko, and Markiyan Shashkevych, in their view, were the "awakeners" and "founders" of a language and literature that were not limited to administrative borders. However, the objective reality made its own corrections, so when organizing the celebrations, the positions of the Greek-Catholic clergy, the Polish administration of the region, and Austrian officials had to be taken into account. It turned out that the figure of Markiyan Shashkevych was the least controversial, while Shevchenko or the living classic Ivan Franko were subject to questions from both the church and the authorities.

Ukrainian Patriotic Calendar and the Efforts to Mark the Urban Space

Objectively, Ukrainians had fewer opportunities (economic, political, organizational, and even human) than Poles to manifest the presence of their literature in Lviv. Celebrations dedicated to the birth or death of poets or to the anniversaries of books were, as a rule, rather intimate. They were held inside, in the premises of societies or reading rooms, etc. These were mainly the Shevchenko Days, celebrated in March.

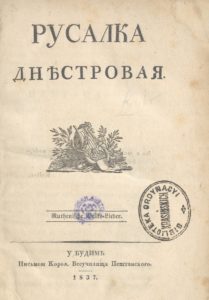

In 1888 the 50th anniversary of the publication of the almanac Rusalka Dnistrova was celebrated in the National House. According to the periodical Dilo, this festivity did not become a celebration of Slavic solidarity because of "national egoism" (apparently Polish). Nevertheless, numerous delegates from the province came to Lviv, the meeting in the National House concluded with a concert, and the celebration continued in a restaurant.

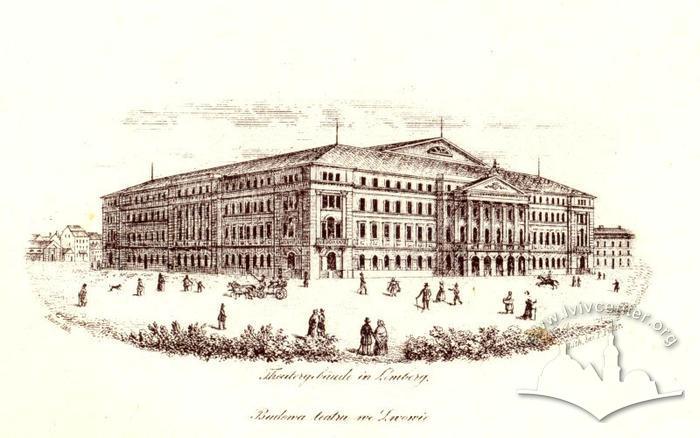

In 1898 the Shevchenko Scientific Society, headed by Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, organized a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the publication of Ivan Kotliarevskyi's Aeneid. 1898 was a year of anniversaries: 25 years of Ivan Franko's creative activity, 50 years of the abolition of corvee labor, 50 years of the Council (Sobor) of Ruthenian Scholars, 60 years of Ivan Kotliarevskyi's death, 250 years of the beginning of the Khmelnytskyi Uprising. The main event, however, was the 100th anniversary of the publication of the Aeneid, the first literary work in the modern Ukrainian language. Various public organizations and representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia, including those from the Russian-occupied part of Ukraine, were invited to participate in the celebration of the 100th anniversary of the Aeneid. The author of Natalka Poltavka, Mykola Lysenko, came, and the opera itself was performed on October 31, 1898, at the Skarbek Theater On November 1, a "scientific meeting" was held in the National House, and in the evening a festive dinner for 200 guests was held in the Postal Club Hall in the George Hotel. During the two days, the police made sure that there was no excessive criticism of the Russian Empire, that no anti-state ideas were spread, and that no mention was made of Khmelnytskyi's uprising. However, there were no objections to the performance of the anthem "Shche ne vmerla Ukraina." As in the case of the Polish anniversary of Mickiewicz, Lviv was not the center of the celebrations on a national level: Poltava was.

In 1911, the Prosvita Society participated in the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the death of Taras Shevchenko. In the Russian Empire, commemorations of the anniversary were forbidden, so Galicia (as in the case of the Polish "poet-prophets") was responsible for the all-national level. Church services, meetings, concerts, monuments and publications were held in the region for a long time, but the political reality of the time did not allow for a large-scale event in Lviv.

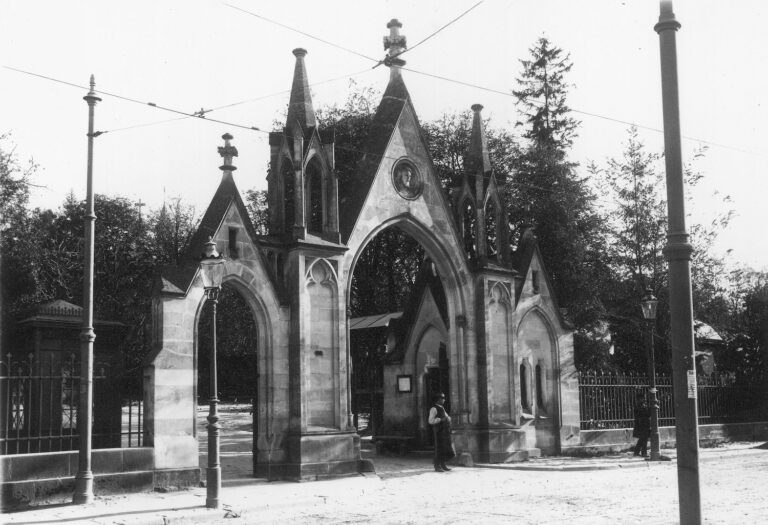

However, the most important and massive (up to 10,000 participants) Ukrainian event in Lviv in 1911, again organized by Prosvita, was the 100th anniversary of Markiyan Shashkevych. Actually, only this event can be considered as one in which Ukrainians "came out" into the public space of the city of Lviv, beyond the walls of societies and churches. Obviously, this did not happen because the Galicians venerated Shashkevych more than Shevchenko, but because several factors came together. The figure of the Greek-Catholic priest and Romantic poet did not provoke as much resistance from the elites as the figure of the "Orthodox revolutionary" Shevchenko. By that time, Shashkevych had already been George Hotel, which meant that a legal pilgrimage site had been established. In fact, in the absence of monuments in the city center (which only the Poles could afford), the monument at the Lychakiv cemetery fulfilled the same role. Besides, Markiyan Shashkevych was a local.

The Polish democratic newspaper Kurjer Lwowski devoted a large article to Shashkevych, calling the poet "the glory and pride of Rus" and "the first to write in the vernacular, which others despised." The editorial board was complimentary about Markiyan Shashkevych because he fit into the democratic idea that the oppressed peoples of Austria had the right to have a voice in contemporary literature, not because he was a pioneer of Ukrainian literature in Galicia.

On Sunday, November 5, delegates from all over the province gathered in St. George's Square. After a solemn service they unveiled a memorial plaque on the wall of the cathedral and at noon they marched to the Lychakiv cemetery to visit Shashkevych's grave.

The march was led by members of the Sich Society on horseback, followed by a peasant choir, members of the Sokil Society, university students, schoolchildren from Lviv and the province, representatives of political parties and organizations, and clergymen. At the cemetery, the members of the Sokil lined up in a square with clergymen, leaders of organizations and guests of honor. Then wreaths were laid and Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi delivered a speech from a specially erected platform. The ceremony at the cemetery ended with the singing of the national anthem.

In the afternoon Ukrainians gave lectures in the reading rooms, and in the evening there was a concert in the National House and a theatrical performance in the hall of the Yad Haruzim Society. On the following Monday there were no classes in all the people's schools and in the Ruthenian gymnasium. A memorial service was held at the Greek Catholic Theological Seminary and another memorial plaque was unveiled. On two evenings, Monday and Tuesday, special concerts were held at the Philharmonic.

An even bigger event was the Shevchenko Sokil rally of 1914, but one may wonder how much of it was a desire to honor Taras Shevchenko and how much was a desire to demonstrate the organizational and coercive capabilities of the Ukrainian movement under this pretext.

* * *

Thus the Ukrainians, following the Poles, began to build their own "national pantheon" with the necessary attributes. And while there were no problems with the calendar — there were anniversaries and annual Shevchenko Days — there were problems with the memorial sites. Only the grave of Markiyan Shashkevych, a non-controversial figure, was declared a place of pilgrimage. A monument to Taras Shevchenko in Lviv was out of the question for the foreseeable future. Despite the initiative of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, the Polish elites would not allow it, and both some clergy and Russophiles would have definitely opposed it.

As with other mass events, it was also desirable to enlist the support of the church and to organize the arrival of activists from the province to Lviv. Therefore, it is natural that the real entry of Ukrainians into the public space of Lviv, even with its marking with memorial plaques, took place in 1911 and was timed to coincide with the 100th anniversary of the village priest Markiyan Shashkevych.