The Great War intensified political processes that seemed to have died down due to the limitations imposed by military administrations. Local politicians, however, continued to look for ways to express themselves in the urban space; some rituals had to be abandoned, indeed, but new ones appeared instead. The war accelerated and crystallized all political processes, events began to develop very rapidly, the rhetoric of politicians became more inclined toward militarism and "true satisfaction" of national demands. Due to this crystallization, it is possible to see what Polish and Ukrainian national movements achieved in the public sphere during the times of Galicia’s autonomy within the Austro-Hungarian empire. We can also see what these processes were leading to, ending in a bloody clash in November 1918. The Poles and Ukrainians had been trying to imitate power through rituals and ceremonies for so long that eventually they decided they were really becoming it. The problem was that there were two new contenders for power but the city was only one.

Those who wanted to have power had to behave like power. For example, national heroes had to be welcomed in the same way as the emperor was welcomed: with a "civil guard" instead of an honour guard of infantrymen and grenadiers, with solemn receptions, torchlight marches and other attributes of power.

Governor's Palace in Lviv. During the Russian occupation, the palace became the residence of the Russian General-Governor

In the meantime, the city itself greatly lost its status. Lviv was no longer perceived as "the capital of the freest region of Poland" or as the center of Ukrainian political life. All the most important things were happening in Warsaw or Kyiv so the eyes of politically engaged citizens were directed towards them.

The war caused censorship to be increased. During the times of autonomy, the press, as is well known, was not only a way of communicating with the audience. It was a way to present oneself "in the world", for example, to convey one’s position to the government. Therefore, if something was written about in Lviv newspapers, it was done not only for readers in Lviv but also for Austrian government officials and politicians in Warsaw, Berlin or St. Petersburg. Consequently, the description of manifestations in Lviv was also aimed at an external audience.

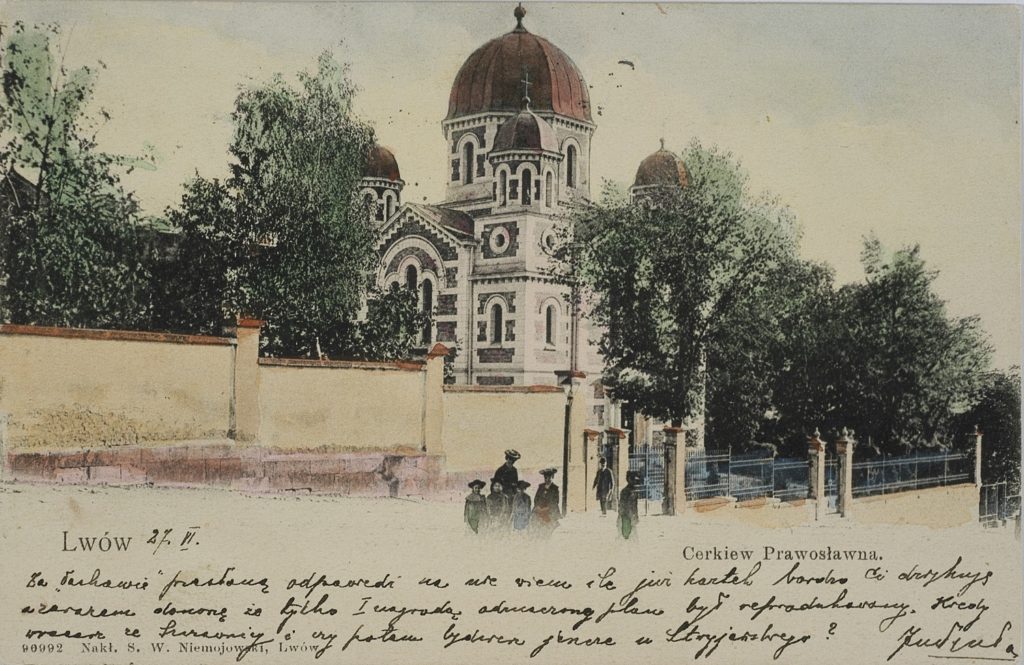

Self-representation through a denomination, which, with the development of modern ideologies, should theoretically lose its importance, got a "second wind" during the Great War. Firstly, it was so because of the occupation of Lviv by the Russians, who emphasized Orthodoxy making the religious issue relevant. Secondly, sometimes religious rituals were becoming the only legal way of self-representation, as it was in the times after the suppression of the Spring of Nations in the mid-19th century.

- Латинська катедра

- Православна церква св. Юрія

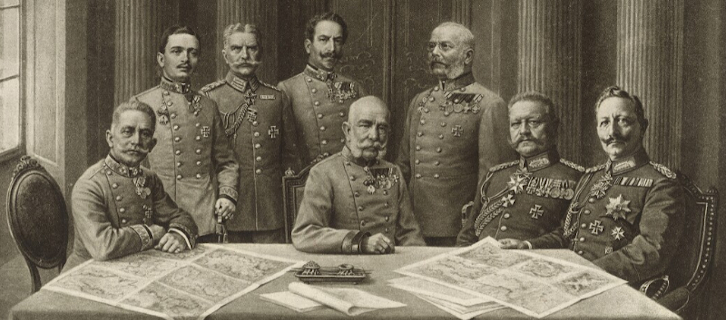

Discussing mass street politics carried out by Polish and Ukrainian activists in Lviv (Jewish activists who supported assimilation can often be added to Polish activists), it is also worth remembering the third side of the "triangle": the Austrian administration. During the war, the Austrians and their allies, the Germans, were in general considered as one political entity. It was not easy for Polish politicians since, not long before, Polish students vandalized the German consulate, the leaders criticized the German policy of assimilating the Poles in what is now Western Poland, while attempts to restore the government's relations with the Ukrainians were branded as a "Prussian intrigue." The Ukrainians traditionally tried to oppose the Poles through complaints to Vienna, hoping for the support from the Austrians and appealing to legality. The experience of the Great War showed how shaky this position was. After all, Vienna traditionally maneuvered between the Poles and Ukrainians, pursuing its own policy of "local loyalty" in relation to the monarchy.

* * *

For Lviv, the period of the Great War consisted of several successive stages.

At the very beginning of hostilities, when propaganda promised a quick defeat of enemy armies, everyone believed that national ambitions would be realized at the expense of defeated Russia. An unprecedented consolidation of society was observed: Ukrainian and Polish paramilitary organizations held joint rallies, the jubilees of Emperor Francis Joseph became extremely popular and massive again, demonstrations in support of "Austrian weapons" were organized regularly. However, all this, in the end, did not prevent Polish politicians from pulling the blanket over themselves — for instance, allocating budget funds to the "Polish legions" while bypassing the Ukrainian ones. Ukrainian politicians, quite traditionally again, complained about the Poles to the governor and directly to Vienna.

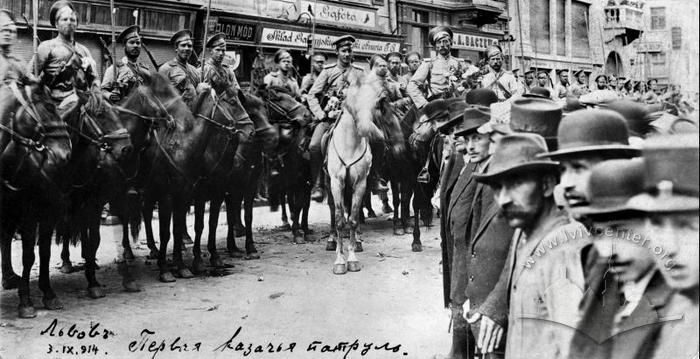

During the Russian occupation of Lviv (September 3, 1914 — June 22, 1915), along with the logical and predictable change in the political course, a "renaissance" of religious life took place. Catholic feasts, which were now celebrated not according to the official calendar, became almost the only legal way for Polish national representation. Commemorating the anniversaries of the Polish uprisings against Russia was certainly out of the question. The Julian calendar became official in the church, this not meaning, however, that the Ukrainians began to dominate. On the contrary, they were seen as a misunderstanding, as a kind of “irregular” Russians, so even the blessing of water on Epiphany was held simultaneously in two places, on pl. Rynok for Greek Catholics and separately on pl. Francyskański for the Orthodox: soldiers, officials, local Russophiles. An event that could become a mass manifestation was the arrival of Tsar Nicholas II in Lviv, but both the organization of the event and the response of the local population were at a significantly lower level than when welcoming Emperor Francis Joseph.

After the liberation of Lviv by the Austrian troops, it seemed that everything would quickly return to the usual schedule. Indeed, Polish traditional "tours" were restored, all imperial celebrations were observed again. The successes at the frontline, however, were not impressive, a large part of Galicia being still occupied by the Russian army, problems of food supply worsening, epidemics of infectious diseases alternating. In addition, the city lost many of its active citizens due to the war, evacuation and deportations. The political activists remaining in Lviv clearly could not maintain the pre-war level of political activity. After all, the city residents often were in no mood for any demonstrations.

In these conditions, national contradictions intensified. The funeral of Ivan Franko on May 31, 1916 was not only a national manifestation but also a demonstration of the mobilization capabilities of the Ukrainians in Lviv. What was vital, however, was the understanding of the inevitability of changes. No one hoped for the restoration of the pre-war status quo, everyone understood that national issues would be resolved on the battlefields. Therefore, while the Austrians invented new ways to make the population more loyal like installing a statue of the Iron Knight and holding an exhibition of trophy military equipment on the anniversary of the liberation of Lviv, national politicians were more concerned with the fate of "their soldiers" in the Austrian army.

Apart from that, the role of Lviv as the center of the political life of "the whole of Poland" was finally eliminated. Considering the Austrian part, it was safer in Krakow, while the main hopes were connected with Warsaw. Something similar happened in the Ukrainian movement, as Ukrainian activists became more and more actively involved in the affairs of Dnieper Ukraine.

In the late 1916, information appeared about the "restoration of independent Poland." This caused quite an upsurge in the Polish political community of Lviv: traditional aristocratic kuntusz garments reappeared in the public space, "hejnals" (bugle calls) were again played from the city hall tower, images of the white eagle were again printed on illumination cards. The square in front of the Union of Lublin mound at the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) hill regained its status as a place for holding patriotic rallies. And most importantly, everyone talked about the Polish legions as the new Polish army. Nevertheless, the main celebrations were held in Krakow and Warsaw.

In 1917, the leaders of the pre-war national life in Lviv came back to the city after being taken away by the Russians during their retreat: the city president Tadeusz Rutowski and the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky. The way they were welcomed can be compared to the visits of the emperor, so great were the desires for self-representation and demonstration of national political ambitions.

The situation changed briefly in 1918, when amid a growing crisis a peace treaty was signed between the Central Powers and the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Peace of Brest meant the consolidation of Chełm Land and Podlasie (which the Poles considered their own) for Ukraine, as well as a growing role of the Ukrainians in the Habsburg Empire with the further division of Galicia into Eastern (Ukrainian) and Western (Polish) parts. On this occasion, the Ukrainians held a massive "feast of peace and Ukrainian statehood", which was the largest event of 1918.

All this, however, did not last long, as in the autumn of 1918 the situation changed again not in favour of the Ukrainians, when the government decided not to stake on Ukraine and once again refocused on the Poles; after the October manifesto of Emperor Charles I, it generally became clear that now everyone was fighting for oneself. Ironically, both the Ukrainians and Poles held their first rallies in an "almost independent" status near their archbishopric cathedrals, that is, allegedly returning to the starting point of "national-denominational identification" — this time with the experience of street political confrontation during the Habsburg autonomy, though, as well as with faith in "their own armies", which were supposed to decide the destiny of the city. After all, that was precisely what the events of November 1918 showed.