During the period of autonomy, numerous patriotic events were regularly held in Lviv to mark various historical events. These were often all-Polish anniversaries or anniversaries of the January or November Uprisings, the 3rd May Constitution Day, etc. Sometimes these were Ruthenian/Ukrainian ecclesiastical or social anniversaries like the Union of Brest, the baptism of Rus, or the abolition of the corvee labour. However, there were also examples of truly local dates dedicated to events from Lviv's past.

The rituals themselves were not original. One way or another, it was either an imitation of what was already happening in the city during the emperor's visits and religious practices, or borrowing Western progressive models of modern political life. Therefore, when analyzing these events, the interpretation, arguments and explanations of "why this was being done" have more weight than anything else; more precisely, it is important to see how local history was woven into the national narrative and used in the political struggle.

Quite logically, the City Council played a key role here, justifying their self-assigned title of "the most patriotic and democratic center of Polish life in the three parts of divided Poland." In general, in the triangle formed by the governor's office, the Diet (Sejm) and the City Council, each side could be considered patriotic. However, it was the City Council that was the most active in the manifestations of this patriotism, probably due to the fact that it could concentrate exclusively on Lviv, "the capital of the freest region of Poland", instead of scattering efforts in outlying areas, as well as due to less attention from Vienna compared to the attention paid by the capital to the provincial authorities.

To confirm the status of the "most patriotic center", examples were sought in the past illustrating the participation of Lviv "burghers", "guilds", or "associations" in national history. It was due to this policy that two types of "presence in the city" could be discussed at the same time.

The first one was the presence in the past, when the events from the times of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth were used, which substantiated the position of the contemporary City Council that was focused on the "revival of the Motherland." In particular, this category includes the 550th anniversary of the shoemakers' guild and the 350th anniversary of the Rifle Association as examples of the "revival and vitality of the ancient Polish tradition." In the period of Habsburg autonomy, the guilds actually had nothing to do with the medieval regulation of economic relations. These were rather professional clubs or patriotic associations that continued to use the name "guild." For example, every year on December 8 (the feast of the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary according to the Gregorian calendar), the "Feast of the Polish Merchants / Day of the Lviv Merchants' Guild" was celebrated. The association under this name traced its history back to the 1670s, which should testify to the ancient traditions of Polish trade in Lviv. Among other things, the connection to a religious feast enabled a celebration with a clearly Polish patriotic bias even during the Russian occupation of Lviv.

- Ювілей цеху шевців 1907 року / Anniversary of the Shoemakers’ Guild in 1907

- Стрілецьке товариство / Rifle Association (1913)

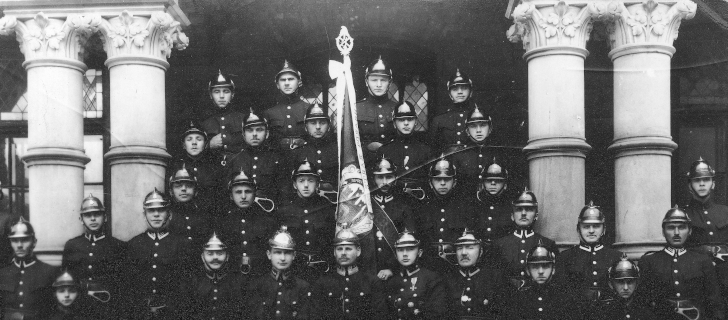

The second type is when the successes of local self-government or merely self-organization were celebrated during the Austrian period. The celebration of the Sokół volunteer fire association anniversary is an example of recent history, which became an argument in the discussion about the province's belonging. This celebration very well illustrates the combination of local and national politics, when the capacity for self-organization implies the capacity for self-governance, and, therefore, in the long run, for statehood. Apart from that, it also illustrates the militarization of national movements and their readiness to resolve conflicts by force.

So, both the "pre-Austrian" history of the "good old days" of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the recent past were used, capable of illustrating the Polish ability to governance and statehood here and now or at least the ability to national revival and "building up society"; the centenary of Franciszek Smolka in 1910 can be cited as the latter's example.

- Ювілей пожежного товариства "Сокіл" / Sokół volunteer fire association anniversary

- Ювілей Францішека Смольки / The centenary of Franciszek Smolka

Discussions about the national affiliation of Lviv between the Poles and Ukrainians, who also used the "past" as a political argument, led to the development of the corresponding infrastructure. For example, it was at that time that, in addition to organizations like the Polish Historical Society, thanks to the efforts of historians such as Aleksander Czołowski and the support of the local political elite, the Historical Museum of the City of Lviv and the King Jan III National Museum were opened in Lviv. Apart from that, the anniversary of the siege of Lviv by the troops of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and the celebration of the founding date of Lviv University are excellent illustrations of how conflict-prone historical memory was in the conditions of the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation.

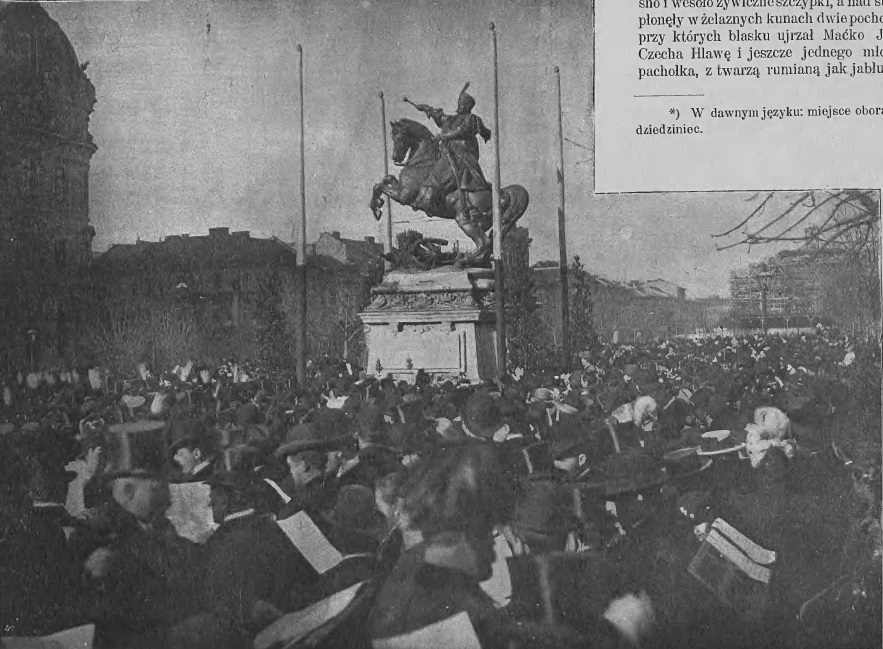

However, local history was not always easily reconciled with Vienna's politics. The honouring of Jan Sobieski, the Polish king and the "saviour of Vienna", was rather an exception in this regard. Sometimes these things were quite controversial. In this case, commemorations were held as purely non-political events, as mourning services without any speeches or rallies, or merely as the installation of rather neutral memorial signs. If doing this did not result in any reprisals from the empire, if it was clear that Vienna was not against it and the autonomy allowed it, then over time, several years later, the commemoration developed into a national manifestation. This was the case, for example, with the rallies on the Hill of Executions in honour of Wiśniowski and Kapuściński, who were rebels against the empire executed by the Austrians in Lviv.

- Встановлення пам'ятника Яну ІІІ Собєському (1898) / The erection of the monument to Jan III Sobieski (1898)

- Роковини Вішньовського і Капусцінського / Anniversaries of Wiśniowski and Kapuściński

Instead, the idea of celebrating the anniversary of the shelling of Lviv by Austrian troops on November 1, 1848, during the suppression of the Spring of Nations, did not take root. Perhaps, it was due to the fact that the uprising did not bring success to the Poles, and in the end the idea of "organic labour" won in Galicia, or there just was no hero to personalize this event. It is also possible that the Polish political activists did not want to remind one more time of the historic event, which Ukrainians interpreted as their release "from the Polish captivity", i.e. the abolition of the corvee labour, and as the time of their national movement’s birth. Apart from that, the reason coulds be trivial pressure on the part of the central government.