Apart from the fact that Lviv was the center of three metropolitanates (Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic and Armenian), important elements of the city’s religious mosaic included a large Jewish community, as well as a notable Protestant community. When it comes to purposeful political representation with the use of religious instruments, the main actors were the Roman Catholic Poles and the Greek Catholic Ukrainians. For them, this presence in the city was part of the struggle for Lviv as a center of their "national revival." In this situation, the Armenian Church acted and looked like a part of the "Polish project."

Mostly the mass events taking place in Habsburg Lviv contained religious elements. These were solemn or mourning services (ceremonies) in churches, timed to certain dates, or prayers before processions or rallies, various consecrations, etc. In addition, purely religious events were also held, on whose example one can see not the sacralization of the political (such as the blessing of a rally or procession), but the politicization of the religious (when a purely church event acquired a national or political character).

Religious rituals probably became the basis for the later practices of mass events in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. After the suppression of the Spring of Nations, virtually all permitted mass events in the city were of a purely religious nature. Any other events were merely not allowed (though regularly "made up" by special religious services dedicated to the life of the royal family).

Actually, religious events, as well as celebrations related to the emperor, were the basis for all other rituals in Lviv during the period of autonomy (if we do not take into account direct borrowings from the European political fashion of the time, such as rallies, assemblies or gatherings). Solemn processions were transformed into marches, sermons into speeches, and there was also an evolution of the tradition of joint singing of anthems and the like.

In Eastern Galicia, denominational affiliation almost always determined the national affiliation as well. National-denominational differences were additionally emphasized by calendar differences as religious holidays celebrated according to "one’s own" — "Polish" (Gregorian) and "Ruthenian" (Julian) — calendar automatically became "national." This applied both to Christmas and Easter and other holidays common to all Christians. It is also about participation in the ceremonies dedicated to the beginning and end of the academic year, as well as about the tradition of the first communion for schoolchildren, which was conducted by Greek Catholic priests in Ruthenian institutions and by Roman Catholic priests in Polish ones.

Some holidays were specific to "their" denomination and accompanied by specific ways of celebration. In particular, it is worth mentioning the celebration of Epiphany by Greek Catholics and Corpus Christi by Roman Catholics in Lviv.

The situation in which national affiliation was identified with that religious meant an additional opportunity for national groups to manifest their existence in the city under a religious pretext. In the 1890s, the fairs near St. George's Cathedral, which traditionally took place on St. George's Day on May 6 and on the Feast of the Protection of the Virgin on October 14, no longer played the same role as before. However, many Ruthenian peasants from the surrounding villages still kept coming to these fairs, which made it possible to demonstrate the "presence" of Ruthenians in Lviv at least twice a year. There were also traditional processions at the cemetery: during the Pentecost, also known as the Green Holidays (according to the Julian calendar), memorial services for Mykhailo Kachkovsky, a patron of writers and publicists, as well as various consecrations, etc.

For the Ruthenians, who had no aristocracy of their own, almost no representation in the city self-government bodies and just a small number of nationally active citizens, the church hierarchs were their chief (if not the only) representatives in Lviv. They were considered "fathers of the nation" and represented it at the highest level as an elite. Therefore, it was the church that often took over the organization of events, which at first glance did not have a religious character, but were important for its congregation, in particular, in a national sense. For example, the anniversary of the abolition of corvee labour.

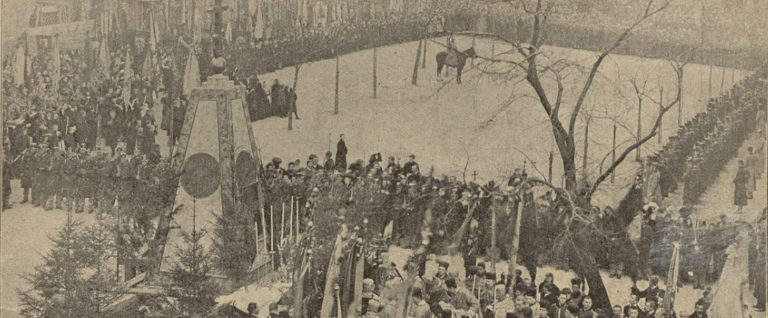

For the hierarchs of both denominations lavish enthronements, were organized, being perhaps the most solemn religious ceremonies in the city. These events were usually accompanied by processions through the city and solemn church celebrations; gauging by the number of people or the involvement of the military, loyalty of the "people" and the authorities to the new hierarch could be determined.

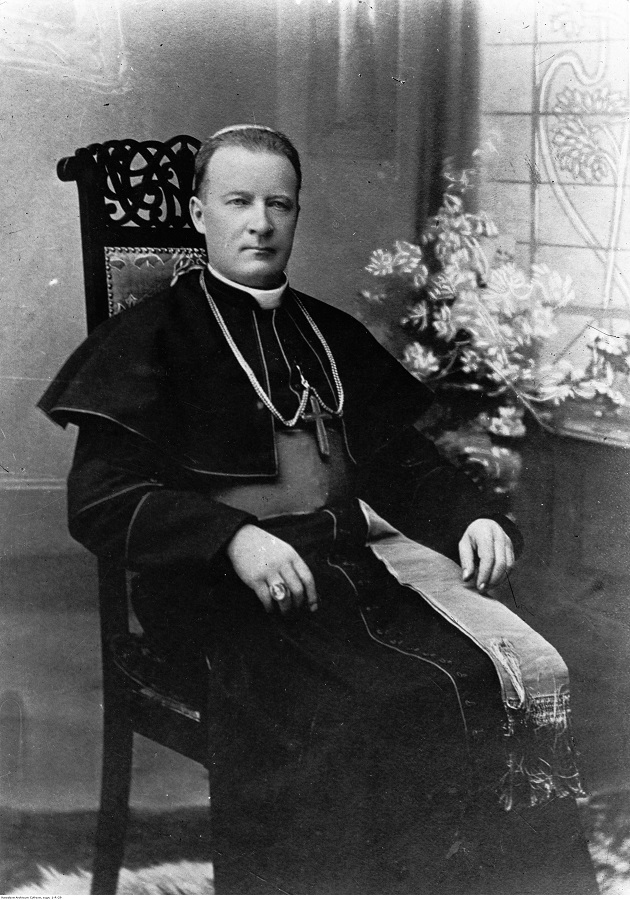

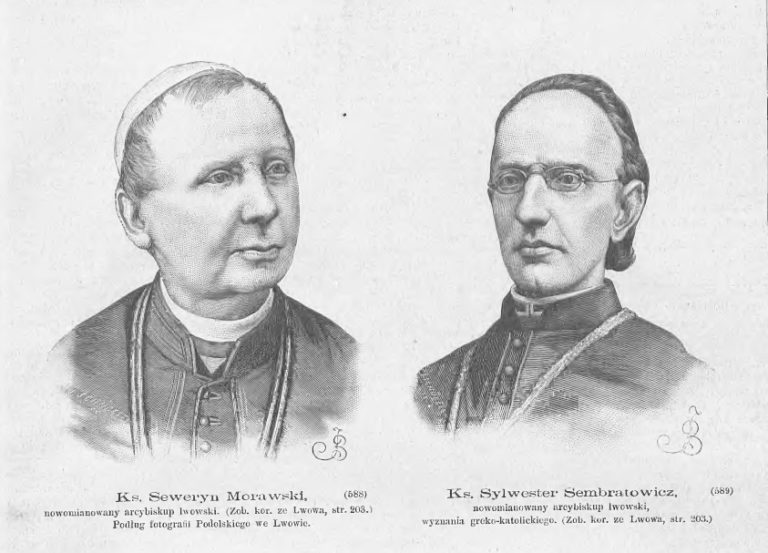

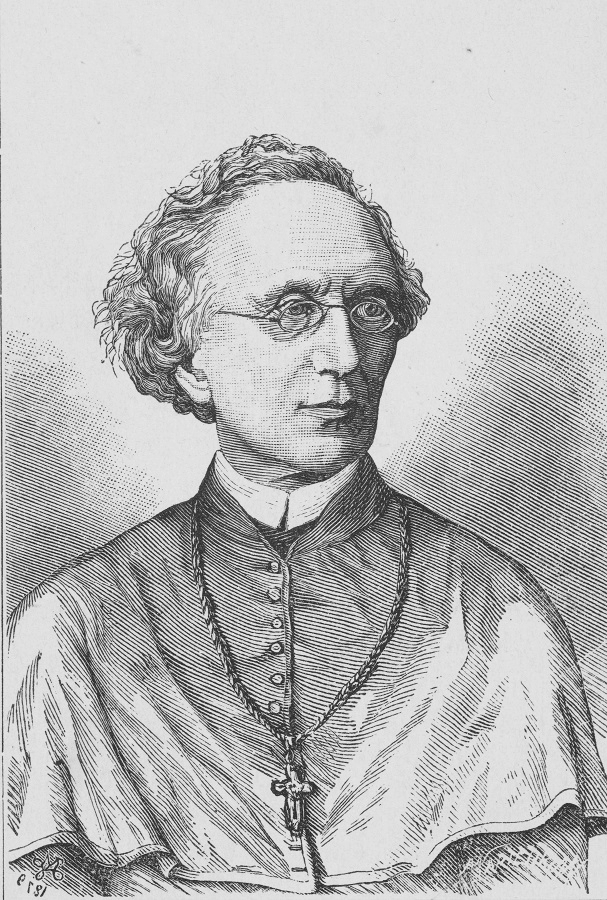

Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovich

Considering the importance of the Greek Catholic clergy for the Ukrainians, these enthronements were to demonstrate the role of the metropolitan in the life of Galician Ukrainians, and the role of the Ukrainians themselves in the life of the province. For instance, the enthronements of Andrey Sheptytsky on the episcopal throne in 1898 and on the metrohttps://lviv-center.maps.arcgis.com/home/index.html?sortField=modified&sortOrder=desc&view=table#mypolitan throne in 1901 can be mentioned. These celebrations did not always have to be large-scale, as evidenced by, for example, the modest enthronement ceremony of Metropolitan Yulian Sas-Kuilovsky in 1899.

Over time, the rituals, which at first glance had a purely religious character, acquired an increasingly distinct national colour. For example, the funerals of famous figures which by default should have been a purely spiritual rite, turned into large-scale national manifestations, such as the reburial of Markiyan Shashkevych, which became truly massive and "national."

"National" religious calendars were formed. It was also about such annual commemorative dates as "Polish" memorial days and "Ruthenian" Green Holidays (Pentecost), as well as about the "invention" of national anniversaries with a religious context, such as the anniversaries of Jan Casimir’s “vows”, the anniversaries of the baptism of Rus in 1888 or the Union of Brest in 1896, in the celebration of which the church took an active part. This process was accompanied by a confrontation between Russophiles and Ukrainophiles within the Ukrainian national movement, as well as a competition between the clerical and secular parts of the intelligentsia.

In the late 19th century, the Greek Catholic Church under the leadership of Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych took steps to get closer to Rome. On the one hand, this ensured the support of the authorities; on the other hand, however, this meant also ignoring or opposition on the part of the majority of Ruthenian politicians.

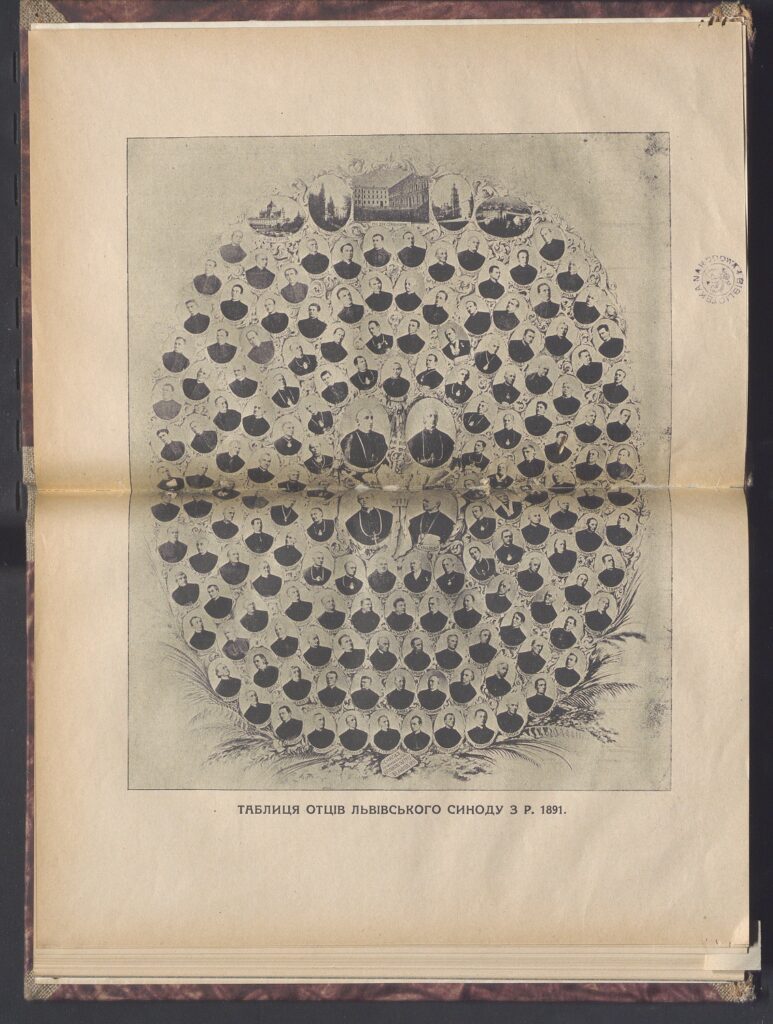

For example, the celebrations on the occasion of the Lviv Provincial Synod in 1891 were appropriate to the clergy’s leading role in Ruthenian society. There were meetings and farewells at the railway station, decorating buildings, and ringing bells in the city churches. Instead, the small number of participants in the procession testified to the tension in the society, concerned about "the metropolitan's intentions to polonize the church."

Tables of the 1891 Lviv Synod fathers

Similarly, when in 1893 the Catholic Church celebrated the 50th anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s episcopacy, it became an opportunity for Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych to demonstrate the loyalty of the Ruthenians to the Apostolic See. The governor, the provincial marshal, Latin and Armenian archbishops were present at the celebration, musical accompaniment was provided by a choir of 200 singers. Russophiles were removed from the organization of the celebration, which was supposed to take place in the People's House. However, the event turned into a disgrace for the organizers and a loss of reputation for the metropolitan as he was met at the People's House with shouts of "Go away!", while in the hall some shouted the name of the village of Tuchapy, whose residents had recently converted from Greek Catholicism to Roman Catholicism.

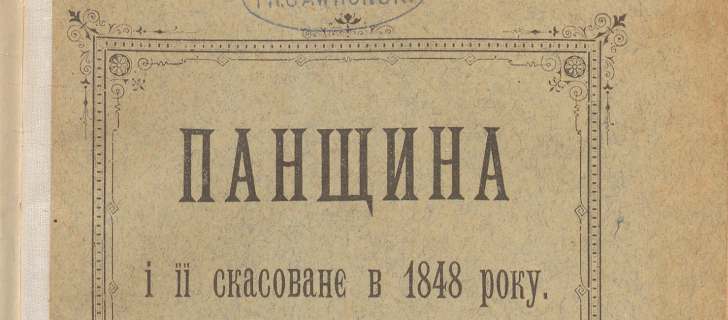

Due to the distinct conflict between the hierarchy and secular politicians, the 50-year anniversary of the abolition of corvee labour on May 3 (15), 1898, was marked not only by concerts and religious services or a wide list of locations, but also by the competition of two organizational committees, a secular one and a church one, and, consequently, holding two parallel events.

Under Sheptytsky, in the following years and up to the First World War, the Greek Catholic Church in Lviv, which in Sembratovych's time was in a certain opposition to the populists, did not show excessive political activity during the organization of mass events, but left this matter to the politicians themselves, providing them with full support at the same time.

For the Roman Catholic Church in Lviv, the issue of "national representation" was not as acute as for the Greek Catholic Church. Polish secular elites, including at various levels of government, coped with this role quite well. The Roman Catholic clergy joined various political actions organized by Polish activists, for example, during the celebration of national anniversaries; however, the clergy began to energetically act in the "national-political field" as late as the early 20th century.

As socialism grew in popularity, the church responded to new challenges by using (and thereby reinforcing) national narratives. This happened, in particular, with the holding of the mentioned Catholic assembly in 1896. The stronger the ideological pressure of the left wing, the more active the position of the hierarchy was. An example of this is Archbishop Józef Bilczewski’s activity.

Archbishop Bilczewski believed that the mere fulfilling of pastoral duties was not enough, that priests had to work on improving the educational and material level of their parishioners. Guided by the ideas of Catholic corporativism (as a counterweight to left-wing ideas), he supported the Polish Professional Union of Christian Workers (Polskie Zjednoczenie Zawodowe Chrześcijan Robotników) and the Catholic-Social Union (Związek Katolicko-Społeczny), and also initiated the construction of the Catholic House in Lviv.

For the Greek Catholics, the situation was more complicated, because the national issue was closely intertwined with the social issue. It was impossible to pursue a tough policy against the left wing without exposing oneself to criticism and accusations of betraying national interests.

Simultaneously with anti-socialist policy, Bilczewski enthusiastically acted "at the national frontline", for example, he introduced a new cult honouring the Mother of God Częstochowa — the Queen of the Polish Crown. From 1911, the celebration was held on the first Sunday of May. The celebrations in the Latin Cathedral were not marked by originality, as was the list of participants (which included the entire Polish elite of the city and the province, members of societies, organizations, guilds, etc.).

The celebrations on the occasion of the coronation of the icon of the Mother of God, which took place in Lviv on May 27, 1905, had a similar ideological stress. The press emphasized that the last similar event was held in Lviv in 1751, even before the division of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The coronation was initiated by the Jesuits, who returned to Lviv in 1836 (before that, in 1773, the order was abolished by the Austrian authorities). This was enough to talk about the "revival of the city’s Polish character." The picture was complemented by the actual decoration of the icon, made in the form of the "Casimir" and "Jagiellonian" crowns of Poland.

The coronation of the icon of the Virgin Mary in 1905

The celebrations took place on the plac Mariacki with the participation of representatives of the authorities, members of societies, organizations, etc. Festive salutes were organized by the members of the Rifle Association, not the military, as was customary during more "official" events. The main religious services were held in the Jesuit church, from where the solemn procession went through the central streets of the city.

Simultaneously, with the growing popularity of nationalism and socialism, the mass actions of supporters of these ideologies became more and more radical, and the churches had to somehow respond to this. They were faced with a triple challenge: to maintain fidelity to the church canons, to retain the sympathy of patriotic believers and to demonstrate loyalty to the authorities at the same time.

On the eve of the 50th anniversary of the January Uprising, for example, Polish clerics had to draw a distinction between the heroic insurgents of that time and today's "socialist terrorists" who are "fighting against their own people." This, logically, caused a flurry of criticism from nationalists, similar to the later accusations of Ukrainian politicians towards Bishop Hryhoriy Khomyshyn for his alleged servility and "betrayal" of national interests. The uprising itself, as a way of achieving independence, according to the Polish hierarchs, lost to the strategy of "organic labour", because it involved destruction and violence, entailed numerous risks (which was confirmed by the results of the January Uprising itself). In their opinion, the best tribute to the "martyrs" of the January Uprising would be a joint prayer and recognition of their mistakes, which, however, took place against the background of the general glorification of the Polish national movement.

In the interwar period, the Greek Catholic Church found itself in a similar situation, when it was necessary to give a public moral assessment to its revolutionaries. At the same time, when the confrontation with supporters of integral nationalism reached its maximum level, the GCC returned to holding its own religious events with political overtones, organizing the action "Ukrainian Youth to Christ."