The 1869 events are mainly associated with the beginning of raising the mound at the Vysokyi Zamok Hill. However, there was also another important aspect of the anniversary, namely, holding, or rather an attempt at holding a mass commemoration.

* * *

The 1867 constitutional compromise and the beginnings of democratization affected public political life in Lviv as well. Local authorities were given (rather theoretically at the beginning) the right to organize illumination, salutes and fireworks, to decorate buildings with flags and to hold music programs. It was possible to issue orders to close shops for the time of festivities, to create a municipal guard, to hold theatrical performances and solemn church services. The 300th anniversary of the Lublin Union, organized by Franciszek Smolka in 1869, could have become the first example of such a new kind of celebration.

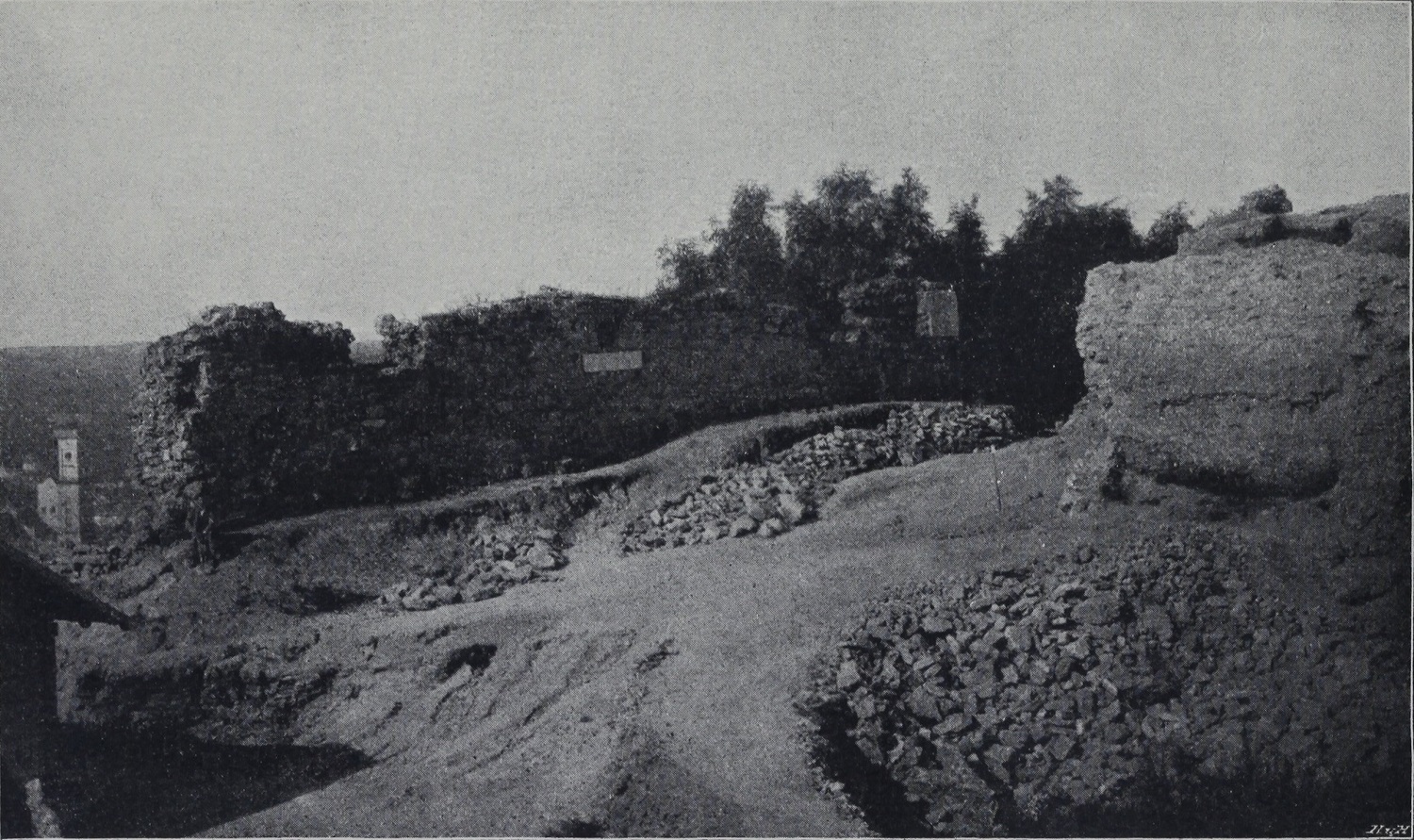

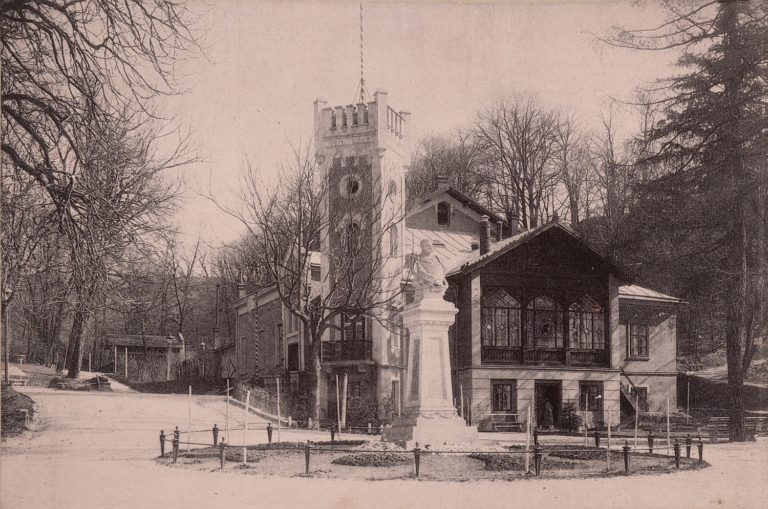

The celebration was accompanied by an initiative to raise a mound at the Vysokyi Zamok Hill. This is the first time that the monument was created on the initiative of some part of society and not on that of government officials. On the one hand, the organizers were inspired by the Kosciuszko Mound in Krakow. On the other hand, the Austrians believed that there was room for imperial symbols in public space, particularly considering the fact that the hill itself was named after Francis Joseph and there were plans to erect a monument in honor of his visit there. Therefore, it is not surprising that the idea of a mound (which symbolized not the Austrian imperial project, but the previous one, with Poland in the lead role) was initially perceived as a radical one.

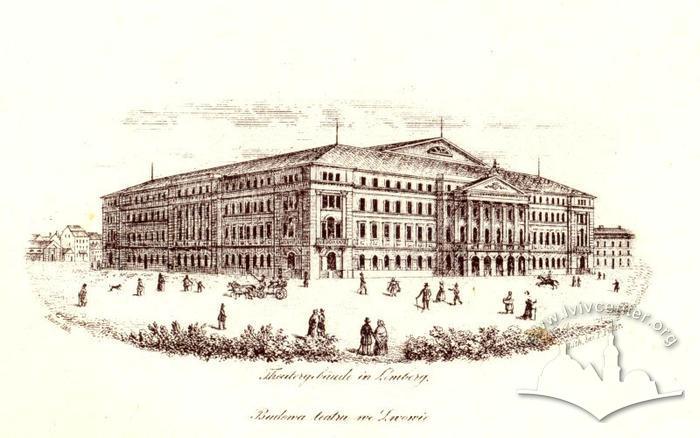

Smolka's proposal for the celebrations of August 10-11, 1869, contained many interesting things. There were to be delegations from the "Slavic peoples," as the event itself was treated as international. Performances at the Skarbek Theater and on a big open-air stage were planned. August 11 was to become an official day off; the day was to begin with 100 cannon volleys and festive divine services in all churches of the city. Residents and guests of Lviv were to gather on the Rynok Square (in national costumes and with national flags) and to go to the Vysokyi Zamok with music. Franciszek Smolka even provided for a civil guard (pol. straż obywatelska). In fact, he wanted to make the entire Austrian imperial ritual serve the national movement.

A civil guard was needed so that no offense would cause the police to interrupt the ceremony. The more global idea was that Poles could control the order in the city themselves, and this could be demonstrated during the celebration. It is even more important that acting in the symbolic field as a government, the Polish democrats seemed to become a government themselves.

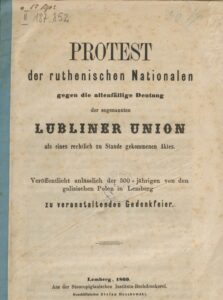

Under the pretext that some Ruthenian politicians opposed Smolka's ideas, the authorities (in order not to provoke conflicts) banned many of what the organizers suggested: a day off, illumination, a solemn march through the city. Actually, participants could attend church services privately and then gather privately in small groups at the Vysokyi Zamok. Anyway, there were some conflicts nevertheless. The brochures "with the Ruthenians' protest against the celebration" were sold "at every corner," causing clashes all day long.

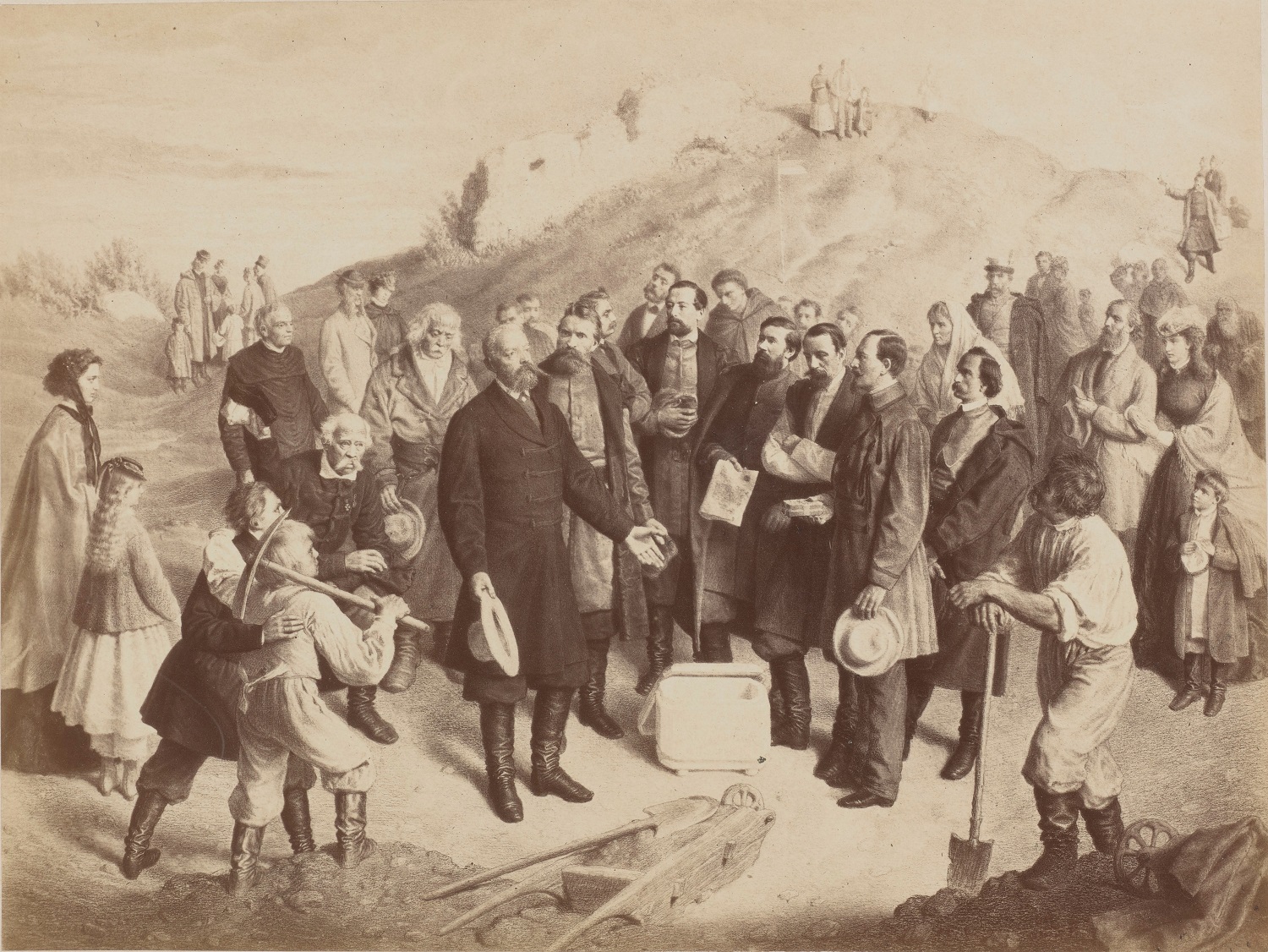

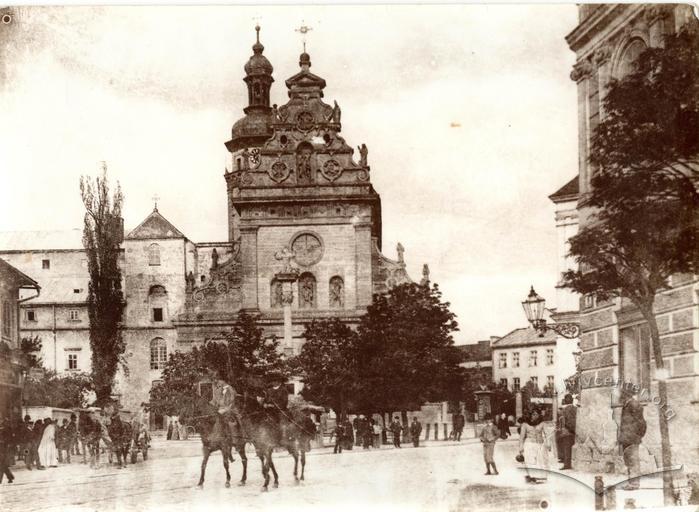

In fact, despite the ambitious plans, the celebrations turned out to be quite modest. The participants gathered in the Dominican and Bernardine churches in small groups only. There were hardly any national costumes, neither aristocrats nor peasants present. In the churches, the priests said cautiously that the Union was an example of brotherhood and love, now embodied in the Habsburg Empire. After that, the audience sang Boże, coś Polskę and Z dymem pożarów and then in small groups proceeded to the Vysokyi Zamok, where about 500 people gathered. A cornerstone was opened there with an inscription reading as follows: "Free among the free and equal among the equal, Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia united by the Union of Lublin on August 11, 1569" and the coats of arms of Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia.

In his speech at the cornerstone, Franciszek Smolka declared that if it were not possible to erect an adequate marble and bronze monument, it should be erected using earth "from all over Poland." This was partly true, as the earth in this case had indeed been transported from Grunwald as well as from the graves of poets and insurgents, etc. But still it was the dismantled walls of a medieval castle that constituted the mound's main part. Later in his speech, Smolka combined God, homeland and democratic principles (this became later the usual for Polish nationalism), and threw the first handful of earth. Representatives of the City Council and guests present at the celebration repeated his action, thus symbolically starting to raise the mound.

Later there was a reception at a restaurant at the Vysokyi Zamok. In the evening, there also was a patriotic program in the theater (though limited by censorship), which included, in addition to Polish, some Lithuanian and Ruthenian elements. In the evening, a number of private apartments in the city center joined the illumination, however both government and Ruthenian institutions did not participate in this.

Smolka's idea of a large national assembly was implemented two years later. On August 13, 1871, the authorities no longer banned but rather co-organized the celebrations, and the City Council became an active participant. Delegates from different parts of Poland arrived. There were national costumes, Polish eagles on flags, and a solemn march to the Vysokyi Zamok. There was a celebration for the guests at the Strzelnica, as well as refreshments in a large tent in the City Park. It was a huge change: the Polish celebrations transformed from private to public format. Although the rituals were similar in both cases (churches, the location at the Vysokyi Zamok, the theater involved), in 1871 it was all consecrated at the highest level, in the Latin cathedral (the main church of the city), and legitimized by a mass march through the city center.