It took place after a crushing defeat in the elections to the Galician Diet (Sejm), when the Ruthenians won 9 out of 142 seats, although theoretically they could have won more than 40.

The event and its context

The curial electoral system provided for the election of deputies to the Diet from the curia of the large landowners, the curia of the bourgeoisie and the curia of the peasants. About half of the Diet deputies were to be elected from the curia of small landowners — peasants. The Ruthenians, having no nobility and without a sufficient number of burghers, could participate in the elections only in the latter curia, and only in the eastern part of the province.

However, instead of the expected 30-40 deputies to the Diet, they won only 9 seats, the fact forcing the Ruthenian elites to make adjustments to their political plans. The viche was supposed to be a turning point in working with the masses, working outside the main representative body of the province. While not rejecting legal methods of parliamentarism, the organizers of the viche spoke of "working with the people, working from below."

The main task set by the organizers was to demonstrate massive popular support for Ruthenian politicians despite their recent electoral defeat. Therefore, the press called on "Ruthenians of all classes to come to Lviv in large numbers" so that the viche "would have more weight in the eyes of the opponents and the government." Lviv, as the center of the province, was a place where the attention of the central government could be drawn. However, realizing that the scale of the Lviv event could only be ensured by the arrival of peasants from the province, Ruthenian politicians distributed announcements through newspapers as follows: "All intelligent Ruthenians of the capital Lviv welcome the numerous citizens and peasants from all over the province who have come to the viche." In fact, the gathering of Galician Ruthenians in Lviv was a kind of "voting with their feet" — a demonstration of mobilization and political influence. Only by using the number of peasants could the Ruthenian politicians somewhat equalize their chances in confronting the landowners, who had better starting opportunities, electing their deputies in the first electoral curia, and influencing the elections in the peasant and city curia. This policy coincided with the emergence of non-aristocratic governance in Austria, where governments began to include representatives of the bourgeoisie. Ultimately, it was in line with the general trend toward emancipation.

The organizers, who included representatives of both Ukrainophile and Russophile organizations, were inspired by the traditional Polish and German party meetings of the time. However, given the specific conditions — the absence of a structured party, the participation of Russophiles and populists — it was decided to interpret the viche as a "public" meeting. Another difference from Western party meetings was the large number of peasants. This factor led to a controversy with the Polish press, which did not perceive the peasantry as a subject of political life. Accordingly, as the national populist periodical Dilo noted, the slogan was not the Polish "for your freedom and ours," but the demand for equality.

As a result, the assembly of 1883 was not a classic viche in the sense of those times, which included the election of delegates, voting, discussions, debates, etc. The essence of the 1883 viche was not about discussions and decisions, but about demonstrating the power of the political movement. Thus, it was another indication of the transition to a new type of politics, where the form and mass character of the event were now valued no less than the content. For example, the Dilo newspaper reported that the Second Ruthenian National Viche was attended by "all strata and all counties of Austrian Ruthenia, mostly peasants and townspeople, as well as priests and secular intellectuals," about 6,000 people in total, and added that "Lviv had never seen such a large congregation of Ruthenian peasants within its walls."

The position of the Greek Catholic Church, the leading Ukrainian institution, was complicated. The hierarchy was still recovering from a high-profile trial of Russophiles, the so-called Olha Hrabar and comrades trial of 1882, which took place after the parish in the village of Hnylychky converted to Orthodoxy as a result of Russophile propaganda, which was prohibited by Austrian law. Participation in another event alongside them as "traitors" and "agents of Moscow" was, to put it mildly, undesirable. In addition, there was social resistance to the reform of the Basilian monasteries carried out by the Jesuits and supported by the Vatican and the central government, the so-called Dobromyl reform, "Polonization" and "Catholicization" from the point of view of the then Ruthenian press. That is why Metropolitan Sylvestr Sembratovych simply left Lviv on the eve of the event for an unscheduled inspection of a deanery. That is, fears or hopes that he would attend the viche were dispelled before it even began.

One of the items on the program of the public meeting was a memorial service for the Greek-Catholic Metropolitan Hryhoriy Yakhymovych in the Church of the Assumption. The Metropolitan had died on April 29, 1863; two months had passed since the 20th anniversary of his death. Hryhoriy Yakhymovych, the head of the Supreme Ruthenian Council in 1848 and an opponent of the introduction of the Latin alphabet, was a unifying figure for Ukrainophiles and Russophiles. Both movements saw something different in his personality. For example, the Academic Circle (Академическій кружокъ) invited "the whole Orthodox world" to attend services in Lviv.

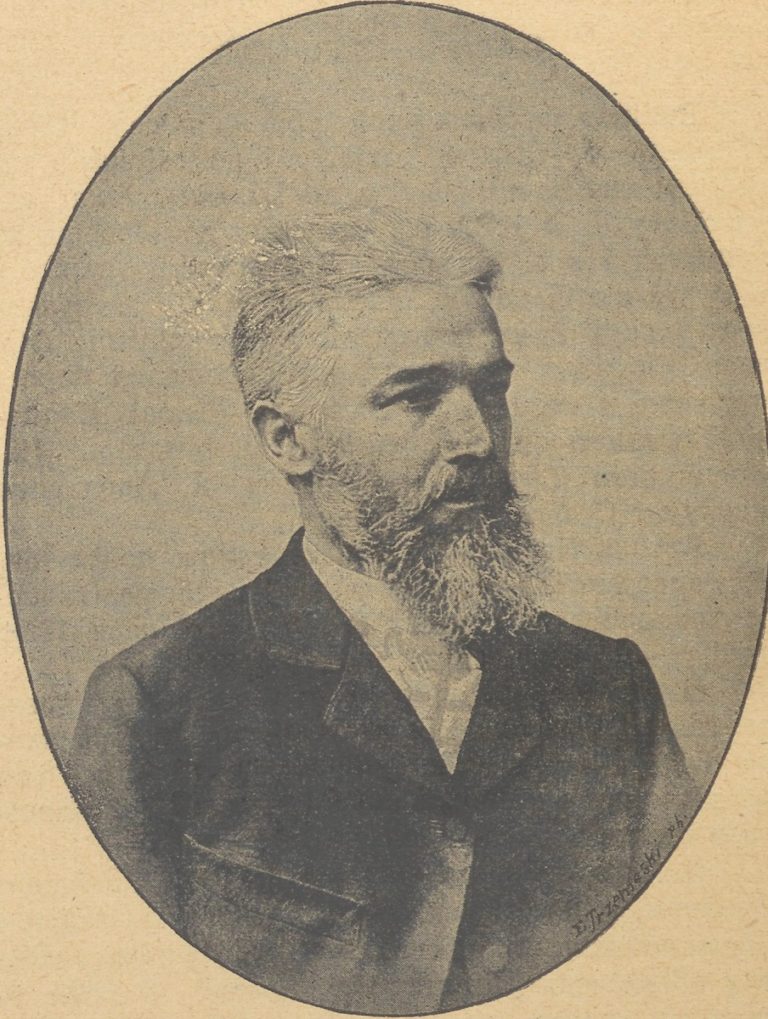

- Григорій Яхимович / Hryhoriy Yakhymovych

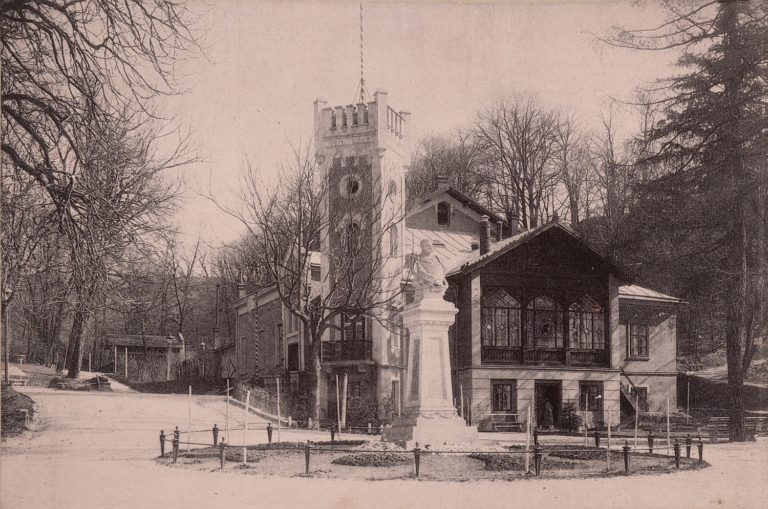

- Успенська церква / Assumption Church

Another important date associated with the day of the Second General National Viche was the anniversary of the death of Emperor Ferdinand I, who had signed the document abolishing corvee labor 35 years earlier, in 1848.

The memorial service was to be followed by the actual meeting, which was to be held in the People's House from 10 a.m. until the evening. Later, in the same hall, there was to be an "evening of music and recitation" in memory of Markiyan Shashkevych, organized by the national populist academic association.

At noon on Thursday, June 28, it turned out that the apartments rented for the delegates were full. Therefore, the "Lviv Ruthenians, mostly students," who met the newcomers at the train station, immediately led them "singing" to the National House and the Ruska Besida building.

The course of the event

So many people gathered for the service in the Church of the Assumption that they could not fit into the church itself and filled the surrounding streets and square. A portrait of Metropolitan Hryhoriy Yakhymovych, decorated with flowers and a blue, yellow and red ribbon with the inscription "To Metropolitan Hryhoriy from the Ruthenian Youth" was placed in the church. This combination of colors could indicate a desire to combine the national colors (blue and yellow) and the colors of the province (blue and red). Otherwise, it could have been a desire to impose an association with "Red Ruthenia", to demonstrate understanding between the populists and the Russophiles. The students kept order.

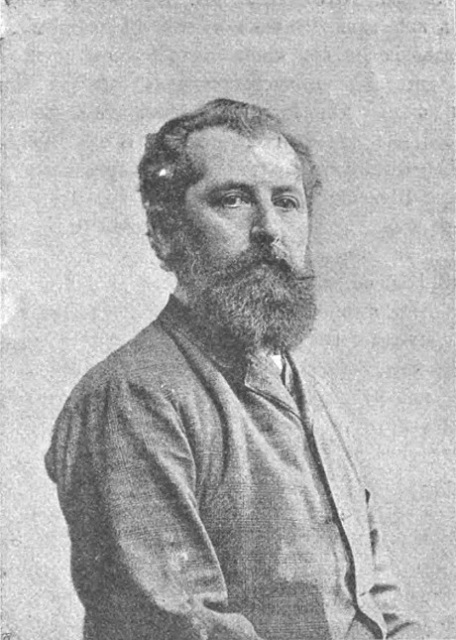

The National House was also crowded: the delegates sat not only in the hall, but also in the corridors, on the stairs and in the courtyard. The viche was chaired by the leaders of Russophile public organizations: Ivan Dobrianskyi and Mykola Antonevych. Populists Vasyl Nahirnyi, Kornylo Ustyianovych, Orest Avdykovskyi and Anatol Vakhnianyn read reports on the economy, education, the Dobromyl reform of the Basilian monasteries and political issues. However, it was the impromptu speeches of the peasant delegates that were most warmly received by the audience.

The authorities were represented by Marynovskyi, the police adviser, and Soboliak, the police commissioner (the presence of the police at mass events and meetings was a common practice at that time). They disrupted the viche when the Russophile Orest Avdykovskyi read a report on the Dobromyl reform, considering the speech provocative and likely to harm the interests of the state.

Several delegates fainted during the speeches, which lasted from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

It is noteworthy that the greetings of the Greek Catholic Church were conveyed not by the Metropolitan, but by Bishop Ivan Stupnytskyi of Przemysl. According to the national populist press, the participants of the viche sympathized with Sylvester Sembratovych's caution and did not condemn him.

After the viche, the delegates went to their hotels for a late lunch. For the organizers, the fact that peasants dined together with intellectuals and priests, even conversing "so calmly and respectfully that the last cynic would agree that they were selected men from their counties," rather than a crowd of peasants, was evidence of the unity of the people. This newspaper controversy with Polish opponents, who called the peasants a mere tool in the hands of Ruthenian politicians, showed another important point. Populists and Russophiles wanted the support of the peasants and were ready to ignore existing social barriers and their positions for the sake of it.

At 7:00 p.m. the popular celebration began, but not in the National House, as planned, but in Strzelnica. The Strzelnica ("shooting range") itself was considered the center of a very conservative Polish organization, the Riflemen Society. Therefore, the fact that during the Ruthenian celebrations, after the National Viche, a concert of the student choir in memory of Markiyan Shashkevych, conducted by Anatol Vakhnianyn, took place there, with Shashkevych's poems recited by Kornylo Ustyianovych, was not a trivial event.

In addition, the visitors, mostly peasants and a small number of city dwellers and priests, were entertained by a military band playing folk dances. The press noted the presence of a large number of Ruthenian women and the sound of "our good Ruthenian language, which could be heard everywhere in the garden."

A "veteran" of the public movement, Fr. Stefan Kachala, was also present: "He looked down from the stage, smiling and remembering 1848."

The festivities ended at 11:00 p.m. as delegates began to disperse to their hotels. Some went straight to the train station.

Interpretation and consequences

The main impact of the Viche was due to its massive scale. Even the organizers had not expected so many participants, which was evident from the lack of accommodation. However, what was a victory for the Ruthenians was interpreted by Polish liberals as evidence of the organizational weakness of the Ukrainian movement. Accordingly, the "people's gathering" was described as "an ignorant mass of deacons and carters, misled by Moscophile priests" (pol. ciemna masa djaków i furmanów, zbałamuconych moskalofilami księżami). Therefore, in their opinion, there was no viche in the classical sense of that time. There was a demonstration, without voting and without debate. Moreover, the peasants, they claimed, had no idea of the matters in question. "The gathering of a crowd of peasants for meetings and decisions on high politics is a mockery of the entire Ruthenian cause," concluded Gazeta Narodowa.

The government-run Gazeta Lwowska also noted the large number of participants, who did not fit into the large hall of the National House. However, it did not consider the event to be "national" because, according to the editorial board, the viche was about state subsidies for the province, flood protection, reducing the costs of local administration, and the need to reorganize the provincial bank in the interests of small landowners. Moreover, there was not a single example of national confrontation.

The participation of Russophiles also became an object of criticism and ridicule in the Polish press. For example, the publication in the Russophile newspaper Novy Prolom of a poem by Olha Hrabar under the pseudonym "Russian Soldier's Wife" calling for participation in the Viche led to ridicule of the "iazychie" in which it was written and a proposal to organize some kind of struggle on the territory of the Russian Empire.

The real consequence of the viche was the damaged relations with the hierarchs of the Greek Catholic Church. This was especially true after the participants decided to send a delegation to the central government to cancel the reform of Basilian monasteries. There was also an increasing involvement of the peasantry in demonstrations and political actions in Lviv.