There was no developed industry in Lviv, so the largest conventionally "proletarian" group was construction workers. They became participants in the strike and riots of 1902, when the economic crisis, accompanied by unemployment and inflation, made the life of wage workers unbearable. Construction workers were all the more vulnerable since they actually only worked 5-6 months a year, weather permitting.

Workers' demonstrations were not something completely unusual for Lviv. For example, a year before, in 1901, workers also tried to write petitions to the governor, gathered in the City Hall and marched to the governor's office. There were also conflicts with the police. However, the riots of 1902 were much more larger and bloodier.

The workers had the following demands: an increase in wages, a reduction in working hours, and at least 2 weeks' notice of dismissal. Strikes, as well as marches of strikers to the city center and rallies in the squares, were a common phenomenon in the early 20th century.

However, in 1902 there were a number of factors that caused the situation to get out of control. First, the economic crisis slowed down the pace of construction significantly. Therefore, the majority of workers could not find work, out of 5,000 (according to some sources, 10,000) workers, only 2,000 had jobs. In this situation employers could manipulate by fining workers or increasing requirements, because two or more unemployed people always applied for one job. In the conditions of this level of unemployment and excess labour, it was constantly rumoured that employers were even going to reduce wage rates.

Secondly, the socialists, who represented the workers’ interests in the negotiations with the employers, created inflated expectations among the strikers. Thirdly, one of the police commissioners decided to use force, although nothing extraordinary (for those times) was happening.

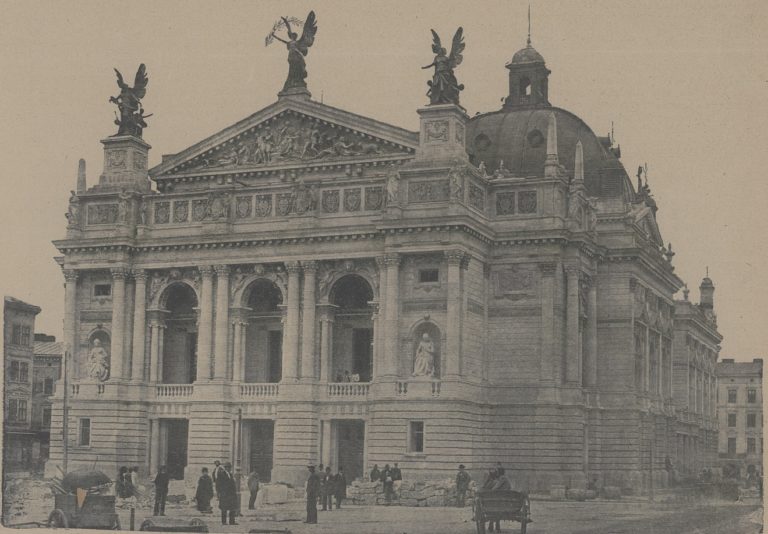

A fragment of a photo from a solemn march to celebrate the 250th anniversary of Lviv University in 1912. One of the few cases when construction workers were photographed: they are dismantling a building on Mickiewicz Square.

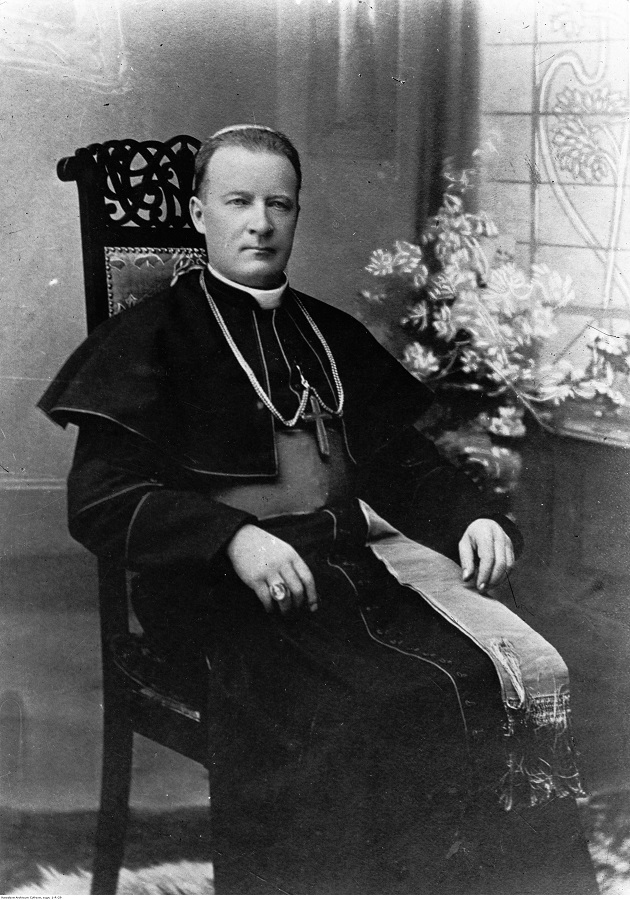

The strike of Lviv construction workers began on May 26, 1902. However, one should not think that the beginning of the strike made any impression on most townspeople or affected the usual way of life. For example, on Thursday, May 29, the celebration of Corpus Christi took place as usual, with grandeur. Thousands of people prayed at the altars on the Rynok Square, the City Hall tower was decorated with green branches. The service, which was conducted on the square by Archbishop Józef Bilczewski, was attended by the entire local elite. After the liturgy, there was a march to pl. St. Spirit, order being ensured by the guard of honour formed by the 15th infantry regiment.

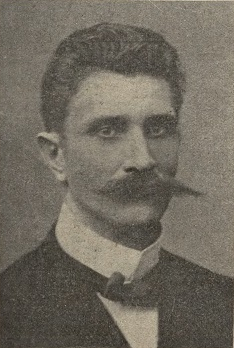

At the same time, the workers, as was customary during strikes, organized their daily marches into the city center: to remind of themselves and their demands and to keep in touch among themselves. In the morning, they gathered near the Ogniwo Construction Workers' Association on ul. Ossolińskich (now vul. Stefanyka 8), where they received the latest information about the course of the strike. During the day, there was a march to pl. Strzelecki and distribution of bread, which was donated by bakeries or bakery workers; sometimes money was also distributed. Part of the strikers gathered near the City Hall, where meetings and negotiations between foremen, entrepreneurs and representatives of workers were held. The places were patrolled by the police; some cavalry troops, hussars, who were stationed in Lviv at that time (the press called them "the Hungarian hussars", probably due to the previous deployment of the 12th hussar regiment) were also involved. Specially appointed persons collected donations, while negotiators like Semen Vityk tried to reach an agreement with the governor.

Stefanyka Street, formerly Ossolińskich Street. In the centre of the photo is house No. 8, where the Ogniwo Association was located in 1902.

In those first days, talks and negotiations between workers and employers were quite unavailing. The construction workers turned to workers of other professions for moral and material support. Also, separately, they addressed the residents of Lviv, as the employers were spreading rumours that the workers were preparing for riots and robberies in the city.

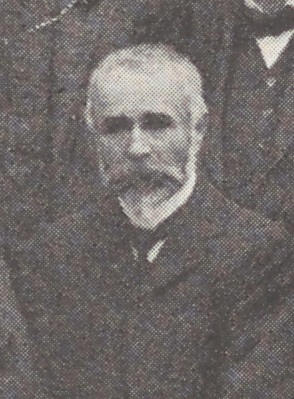

Generally, Sunday, June 1, was the same, but there were some differences. The meeting in the City Hall, mediated by the president of the city of Lviv, Godzimir Małachowski, lasted for a very long time: until 22:30, about 3,000 workers crowding the Rynok Square at that time. The employers allegedly promised not to hire people from outside Lviv, that is, there was a kind of concession on their part. Socialists Semen Vityk, Tadeusz Reger, Józef Hudec and Kornel Żelaszkiewicz rushed to assure the crowd that the negotiations were going in favour of the strikers.

Therefore, when at a new meeting held on pl. Strzelecki on June 2, 1902, it turned out that everything was not so wonderful as it seemed the night before, the workers no longer listened to the left-wing politicians and their persuasions "not to provoke the police." As a result, the troops opened fire on the demonstrators, the Hungarian hussars were dispersing the rally with their sabers, and barricades appeared on the streets of Lviv for the first time since 1848.

Day one: the bloody clashes of June 2, 1902

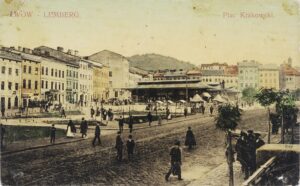

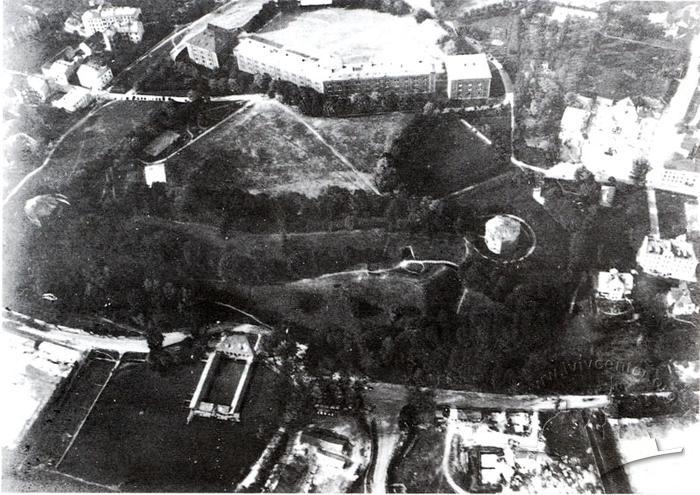

Strzelecki Square, the epicentre of the events. Photo published on the front page of the Krakow-based magazine Ilustracya Polska

Estimates of what happened on June 2, 1902 on pl. Strzelecki ranged from "the police attacked the peaceful demonstrators" to "the workers began to beat innocent soldiers." Either way, the workers were disappointed by the failure of the negotiations. They were encouraged by the fact that bakers had also decided to go on strike on that day. And, most importantly, someone spread a rumour that the soldiers had only empty cartridges. Accordingly, some workers were demonstratively tearing the clothes on their chests while shouting "Shoot!" However, soldiers did not shoot without a command, they simply beat.

As a result of wrangling and jostling, the police commissioner ordered the police and military to disperse the gathering by force. "By force" meant using sabers and guns. A massacre began, at least three demonstrators were shot immediately (a woman among them), many were wounded, two of the latter fatally, as it turned out later. Even more were arrested, the police snatching people from the crowd and locking them in the gateways, perhaps saving them from the hussars and infantry in this way.

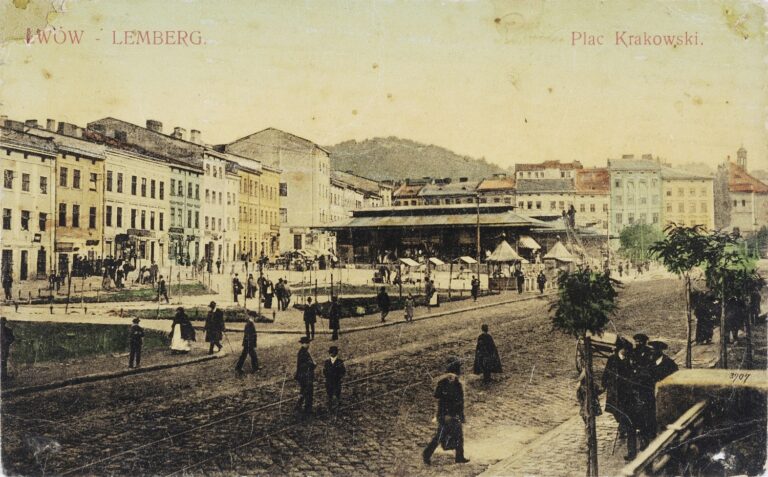

The workers were giving as good as they were getting. A hussar was beaten almost to death after a stone hit him in the head and he fell from his horse. On pl. Krakowski, a crowd tried to lynch a policeman, but he was saved by soldiers. The workers started throwing stones at the soldiers, who responded with a volley from their carbines. On pl. Benedyktyński, the infantrymen came under revolver fire, but a volley from their rifles won again.

The situation resembled not a rally but some kind of spontaneous protests and went far beyond pl. Strzelecki. Mobs attacked the police when there were few of them. And the police grabbed whoever they could and locked them up wherever they could, for example, in the fire department's closet. In the evening, shops had to close, workers and police patrols were constantly hanging around the Rynok Square and pl. Strzelecki. Large groups of people were dispersed by the police threatening to shoot, as happened on pl. Solarni, where around 500 workers gathered. In addition, one could see stretchers with the dead and wounded, women madly screaming and frightened horses there.

The Sztern tavern located on the corner of ul. Grodzickich (now pl. Danyla Halytskoho 13) was completely devastated. There were many bullet marks left on the houses around pl. Strzelecki. Seemingly, the hussars were the most aggressive. They continued to shoot the strikers even after the main confrontation was over.

In the evening and at night, military patrols were on the streets, soldiers on the Citadel were ready to signal them with a three-time cannon volley, roadblocks were set up at the city turnpikes; thanks to this, the night was rather calmly.

Day two: Tuesday, June 3, 1902

After such a large-scale conflict, obviously, everyone began feverishly looking for the culprits and a way out of the situation; another round of negotiations was held in the City Hall. A delegation of workers, headed by Otto Hausner, a member of parliament, visited the governor Leon Piniński and complained about the police commissioner, the soldiers and the hussars. One of the socialist leaders, Herman Diamand, made a similar visit to the police director, Wilhelm Schechtel, asking to withdraw troops from the streets; however, he was refused.

Ignacy Daszyński, a socialist deputy, raised this issue in the State Council. Criticizing the government of Galicia, he mentioned "the murderer who lived in the governor's palace." He said about the Austrian army that it usually ran away from the enemy but fought bravely against unarmed demonstrators.

In Lviv, meanwhile, order had been seemingly restored. The bazaar on the Rynok Square was banned, while most of the shop owners decided not to open. Because of the bakers' strike, there was no bread in the city. Workers and their wives and a lot of police came to the square.

At 9:00 the police tried to arrest a woman who was, however, defended by the crowd and thus able to escape towards ul. Ruska. Then a conflict arose between the workers themselves. By 10:00, several thousand "gloomy and calm" people had gathered in front of the City Hall entrance.

In general, there were few people in the center of the city, most of the shops were closed; only pl. Strzelecki was more or less crowded by curious people looking at the bullet marks and piles of stones. Soldiers and gendarmes were on duty everywhere, allowing only single passers-by through the streets while groups were not allowed. Meanwhile, the infantry on the Rynok Square lined up in a square; the police helped trams pass through groups of workers.

Towards noon, news began to arrive from the outskirts of the city. In particular, an inn was ransacked by a crowd at the Levandivka folwark at night. In the morning, groups of men tried to "take toll" from peasants who were carrying products for sale through the Horodotska turnpike; as a result, they were dispersed by the cavalry. Polytechnic students went on strike.

The police commissioner [Wojciech] Wenc, who ordered the hussars to use their weapons, was blamed by the press for the previous day's bloodshed. Rumours about the atrocities of the protesters spread among the soldiers in the barracks of Lviv; it was decided not to bring the hussars into the city on that day at all.

A black mourning flag was hung from the window of the Ogniwo Association. The construction of the new railway station was going on under the protection of the army.

Meanwhile, politicians and journalists accused the Imperial-Royal Government Correspondence Bureau of sending completely false information about the previous day's events to newspapers "outside Poland."

The arrests continued, and even the wife of a carpenter, who was injured the day before, a mother of three, was arrested for stealing bread. Another woman, an arrested protester’s wife, came to the City Hall to ask for bread; however, she was refused help.

Semen Vityk and Józef Hudec continued to seek an agreement on negotiations.

Towards evening, the situation began to escalate again. Workers blocked the tram traffic; a shootout took place on pl. Mariacki. The crowd on the Rynok Square was constantly increasing, additional troops began to be drawn there, soldiers blocked all the nearby streets, and fresh crowds of protesters were pushing behind the soldiers. After a while, the bulk of the workers were pushed to the monument to Jan Sobieski, where they were blocked both from the side of the City Theater and from pl. Mariacki. At the beginning of ul. Sykstuska, the workers started to be arrested, and when the crowd tried to defend their comrades, the police used their weapons again.

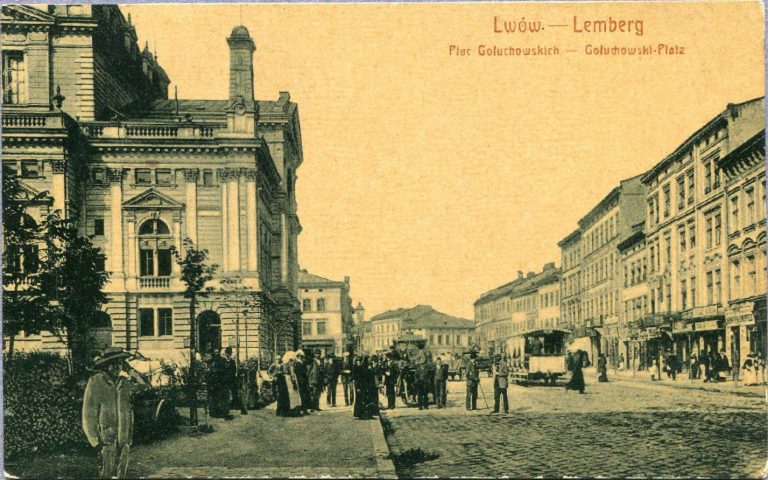

There was nowhere to run, because the gates of the buildings had been closed beforehand, and only a few protesters managed to sneak into the Grand Hotel. One of the workers used a revolver. In the end, the authorities allowed the hussar regiment into the city, the hussars dispersed everyone on the way from ul. Sykstuska to pl. Mariacki, pl. Galicki, ul. Czarneckiego, ul. Podwalna, then through pl. Strzelecki, pl. Krakowski, pl. Gołuchowskich and side streets. Approaches to the Rynok Square and some other intersections were blocked by infantry. All this continued until midnight.

The soldiers were ordered to let through their rows only single "decently dressed" passers-by. This, of course, did not contribute to peace, as the soldiers interpreted such a vague order, given in "a mixture of the German, Polish and Ukrainian languages", quite freely.

Despite this "state of siege", the theaters worked, although there were fewer spectators than usual. Separate groups of workers continued to wander through the center, one crowd even managed to sing "Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła" near the well on pl. Mariacki and then went to pl. Galicki.

At midnight, the army was withdrawn from the city center and only the police remained, the night passed peacefully.

Funerals of the dead. Wednesday, June 4

In the morning, the troops, gendarmerie and police were in constant motion and there were a lot of them in the city center. The military did not let any passers-by to the Rynok Square, so the bazaar sellers were left without customers. The police were on duty at the City Hall entrance and made sure that trams ran without obstacles. A certain worker, who came out to the square in rags (apparently, after spending the night somewhere in a nearby building), was immediately detained, the sellers around lamenting.

The censors tried to limit the leakage of information outside Lviv in every possible way. In Krakow, for example, all printed copies of the newspaper Naprzód was confiscated. Lviv residents wrote to the editorial offices of Lviv newspapers and reported that "the scoundrels assisting the police" were not them but their namesakes. That is, the public clearly sympathized not with the police and even less so with the hussars.

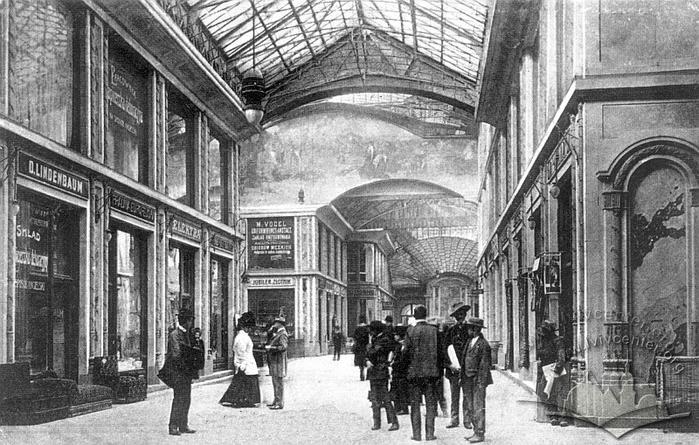

The railway workers' workshops near the station were surrounded by the army as a precaution, so that no one would even try to go there and agitate to join the strike. Some shops even opened at lunchtime, but there were more soldiers and hussars on the streets than potential customers. The Rynok Square was still locked, soldiers standing even at the exits from passages. The authorities did not want a repeat of yesterday's rally at the entrance to the City Hall.

In the meantime, more interesting events were happening on the city outskirts. Gathering on ul. Żółkiewska around 10 a.m., about a hundred men (either the strikers or some local companies of young men) attacked Brummer's bakery, having overturned and looted a cart with bread earlier. Then the bakery owners called the police, the hussars arrived and the crowd retreated. Later, however, two horse-drawn trams arrived, and the protesters used them as a barrier from the cavalry, forcing the passengers and drivers to declare that they were joining the construction workers' strike. Only reinforcements from the police station freed the trams; consequently, two loudest demonstrators were arrested.

At 11:30, another group of about a hundred unemployed people infiltrated the grounds of the sweet factory on ul. Wybranowskiego (now vul. Teslenka). They demanded the shutdown of the factory, which employed approximately 200 people. The staff complied with the protesters' demands and called the police. The "strike" lasted for half an hour until the infantry arrived.

These extraordinary events were happening against the background of reports of bread being stolen from shops, food being extorted in taverns, hungry people begging in the streets and negotiations being under way in the City Hall.

It was the funeral of the victims of the massacre on pl. Strzelecki that turned into a city-wide demonstration. Even before 3 p.m., the workers gathered on ul. Piekarska in front of the chapel. Around 3:30 p.m., Roman Catholic and Greek Catholic priests conducted the funeral rites. Three coffins with two men and one woman were carried by the workers, as well as the flag of the Ogniwo Association and a wreath with an inscription reading "Strikers to the victims."

There were many students, also with a wreath, since the day before, leaflets were distributed in the city with an appeal to show solidarity with the workers. There were wreaths from Social Democrats and even from schoolchildren. Church brotherhoods and organizations came with their standards.

The fact that the burial turned into a demonstration was also emphasized by the route of the funeral procession. From ul. Piekarska, they first reached the gate of the Lychakivsky cemetery, then turned to the church of St. Peter and Paul, then down ul. Łyczakowska. The demonstration was welcomed by St. Anthony church’s bells. Then the column tried to turn to the governor's office through ul. Czarneckiego, but the road was blocked by an infantry unit. So the demonstrators passed through pl. Bernardyński and again went up ul. Łyczakowska towards the Lychakivsky cemetery. The shops were closed all this time.

The ceremony was full of symbolism. The priests of the two rites conducted the funeral together, three coffins were lowered into a common pit. The dead had no families, but, as the newspapers wrote, they had a large working family. The workers sang over the grave Z dymem pożarów and workers' anthems, politicians, activists, representatives of the workers of Przemyśl and Boryslav, Polish and Ukrainian students made speeches. The Kurkowski funeral company took over the expenses.

After the funeral, a short meeting was held on the square near ul. Piekarska. The decision was made to end the strike, to demonstrate mourning for the dead and "not to succumb to police provocations." The latter had to be done already at the beginning of ul. Piekarska, where the police did not allow groups but only one person at a time.

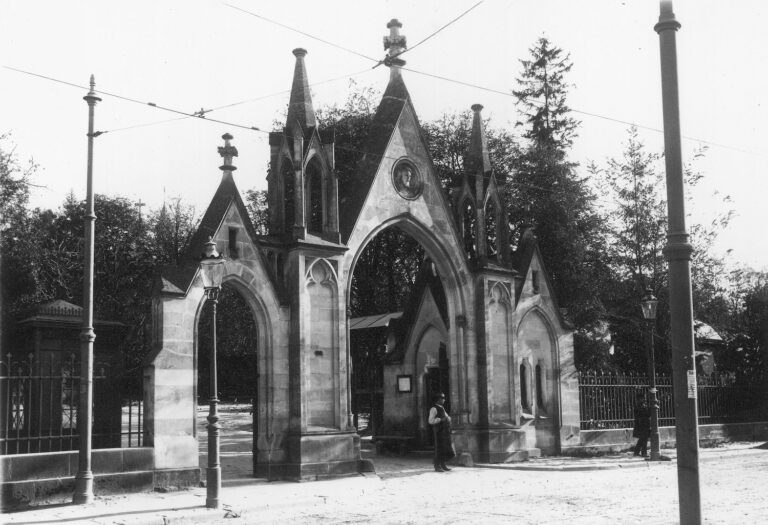

At the same time, a 17-year-old Jewish worker, who had been shot in his thigh on pl. Strzelecki and bled to death 45 minutes later without medical assistance, was also being buried. At first, they tried to bury him without witnesses and demonstrations and nearly managed to bring his body from ul. Szpitalna to the Jewish cemetery. On ul. Janowska, however, those who came to the funeral overtook the hearse, removed the coffin, carried it back to ul. Szpitalna in their arms and from there again carried it to the cemetery. There was panic along the way, as there were many police and people were afraid that the hussars might return. Politicians, including Mykola Hankevych, Herman Diamand and Rabbi Jecheskiel Caro, also spoke over the grave.

In the evening, many people gathered in the Ogniwo Association premises to discuss the agreement with the employers. Bread was distributed to those in need. The army was ready to intervene, but the evening passed peacefully. Theaters, as a sign of solidarity, cancelled their performances and declared mourning.

Interpretation and consequences of the event

On Thursday, when the strike finally stopped, some employers tried to return to the previous conditions, allegedly to "finish the work started." As it turned out, the issue of the payment of masons' labour was dropped from the agenda altogether when the agreement was reached. They were no longer paid attention to, because about a hundred people could not cause any disturbances.

The "unique" version of events was presented by the Gazeta Lwowska, and in the "Chronicle" section, next to openly secondary messages. According to the government-run newspaper journalists, at the call of Semen Vityk, the striking workers went from the Ogniwo Association to pl. Strzelecki. On the way, they tried (unsuccessfully) to take an arrested thief back from the police. On the square, Semen Vityk urged them to disperse, but they did not listen to him. At that time, an infantry unit of the 15th regiment was passing through pl. Strzelecki from training to the barracks. The soldiers were just walking by, when the workers started throwing stones at them. Then the police approached them, but they also threw stones at the police. And it was just then that the senior police commissioner came with the hussars who "cleared the square." Soon the workers gathered again and began to attack the hussars and infantrymen. Consequently, the troops again used both cold arms and firearms. According to this version, similar events took place on pl. Krakowski, on pl. Bernardyński and near the church of Our Lady of the Snows: the workers beat innocent policemen and shot them with revolvers, while the military rescued the latter using their weapons, having previously tried to convince the striking workers with words. The strikers, however, acted irrationally, robbing grocery carts at the city turnpikes at the same time.

In the long run, the workers achieved that the working day should last no longer than 9 hours and 30 minutes, as well as a certain increase in wages. Of the 5,000 strikers, 5 were killed, about 50 were wounded, and several dozen were arrested.

The strike and bloody riots of 1902 were remembered by Lviv residents for a long time. They were not just celebrated, they were necessarily mentioned when the next strikes started, as a reminder that "the main thing was that the bloodshed should not happen again." Also, the workers started from the conditions of 1902, when they bargained for wages and working conditions. This was the case as soon as 1903, when the construction workers went on strike again and even managed to improve their working conditions.

Perhaps it was the June 1902 events in Lviv that caused (or at least encouraged) the peasant strikes of 1902 in Galicia.

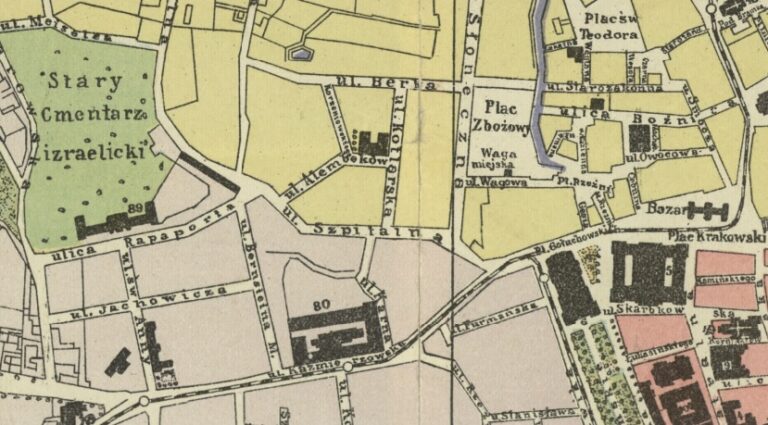

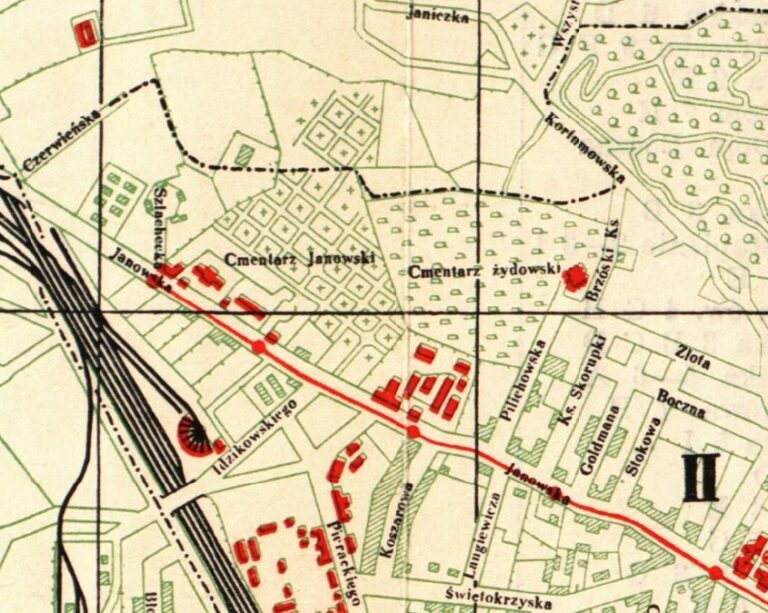

In 1903, on the first anniversary of the bloody demonstration, the first commemoration of it took place, setting a certain standard for commemorating the event. First, a rally and speeches at the Jewish cemetery at the graves of Anchel Hügel and Mojźesz Licht, who died in 1902. After that, a march to the Lychakivsky cemetery along the following route: ul. Janowska, ul. Kazimierzowska, ul. Kołłontaja, ul. Jagiełłońska, ul. Karola Ludwika, pl. Galicki, ul. Piekarska. A thorn wreath (from the Social Democratic Party) and an oak wreath (from the construction workers) were carried, decorated with greenery and red ribbons, in front, instead of a flag, there was a spade wrapped in black cloth. The workers' choir sang, there were many women from the Naprzód Association. Speeches were again delivered and the “Marseillaise" and "Red Flag" were once again sung at the Lychakivsky cemetery over the grave where Franciszek Mikusiński, Jan Sieredzki and Katarzyna Orkisz, who died during the 1902 strike, were buried. Since the Social Democrats were the organizers, they (Hudec, Diamand, Vityk, Melen) made most of the speeches.

A similar commemoration with a march from one cemetery to another was held on June 2, 1912, on the tenth anniversary of the events.