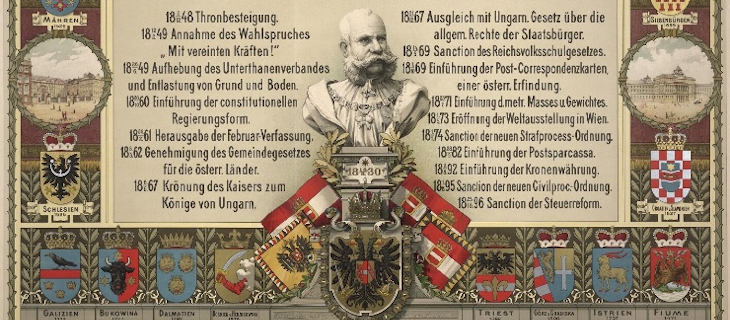

In terms of the empire, Lviv was or was to become an organic part of the Habsburg monarchy, the capital of a crown land and a city with a certain share of identity. To convey this idea to local elites and the population, special rituals were used, among other things.

In the times of neo-absolutism, after the suppression of the Spring of Nations, imperial and religious rituals were actually the only allowed option of street manifestation. Over time, when liberal reforms and autonomy allowed local political activists to openly manifest their views, still new and new meanings were attributed to these rituals. This is very well illustrated, for example, by Emperor Franz Joseph's five visits to Lviv.

The local elites used these opportunities to popularize their ideas or rather to "show their worth" and to "show the city" according to their views and beliefs. The main thing, however, is that these rituals became an example and a basis for further "street" mass politics.

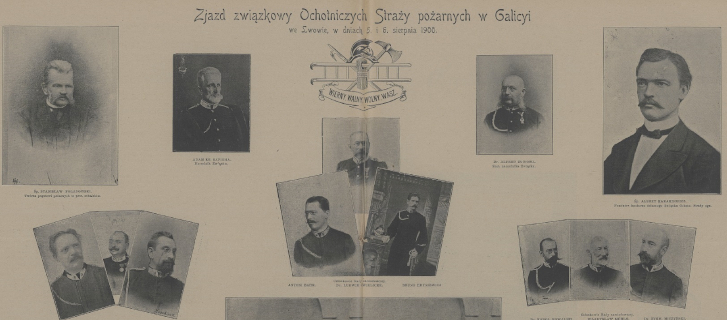

When the imperial policy moved away from neo-absolutism and the period of liberalization began, the urban elites got many other ways to "show themselves" besides religious rituals and imperial visits. These were, in particular, welcoming distinguished guests, marking public space and mass events related to local history.

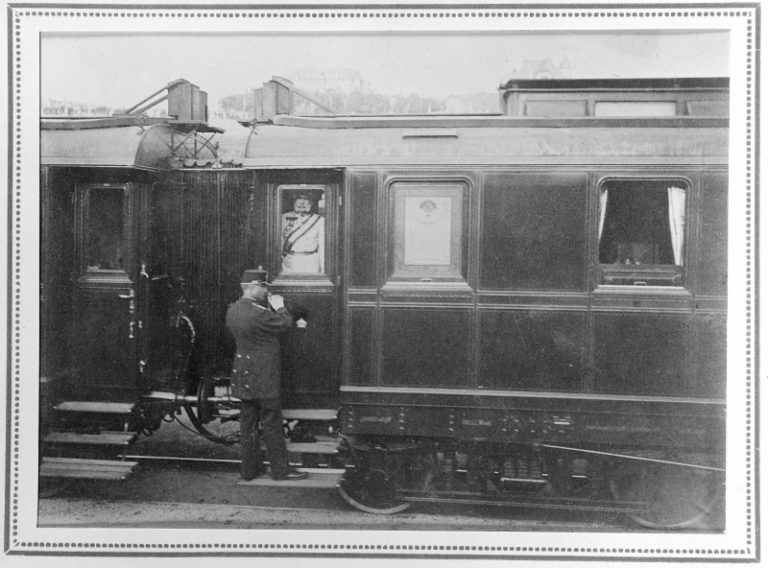

Emperor's visits

Visits by rulers are a worldwide practice, especially widespread at times when societies needed to be consolidated around common ideas, but the means of communication did not yet allow it to be done only remotely.

The emperor was the unifying figure of the state, and the lands ruled by the Habsburgs were officially considered the homeland (although this model did not stand the test of time and the Great War).

His roles during his visits to his subjects were thought out and polished, as were attributes like triumphal arches, guardsmen, serenades under the balcony, etc. Everything was organized in such a way as to demonstrate who had the supreme power. It was within this scenario that the local elites looked for an opportunity to show their worth and their national sympathies.

Franz Joseph visited Lviv five times in half a century, this being a wonderful illustration of the changes that took place from the 1850s to the early 20th century, both in terms of the expansion of the city, technical progress or infrastructure, and as an example of the transformation of domestic politics, when the main security measures changed. This is also a tangible success of emancipation and liberal political reforms, when an estate-based society was replaced by modern bourgeoisie. In the end, this is the evolution of the understanding of what the population of the province was. While at first Franz Joseph was greeted by "representatives of various estates", later he was welcomed by "all the peoples of the province" in their own languages: "Многая літа!" or "Niech żyje!" or "Hoch Keiser!"

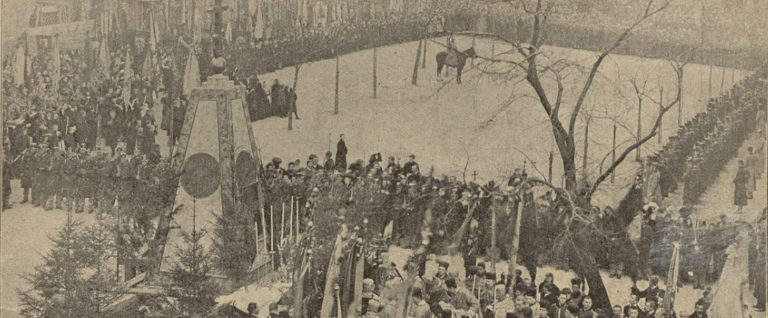

Religious rituals

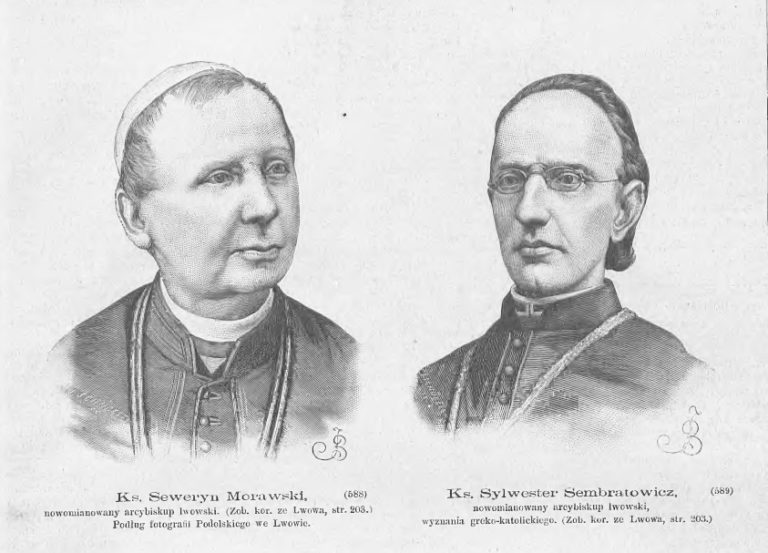

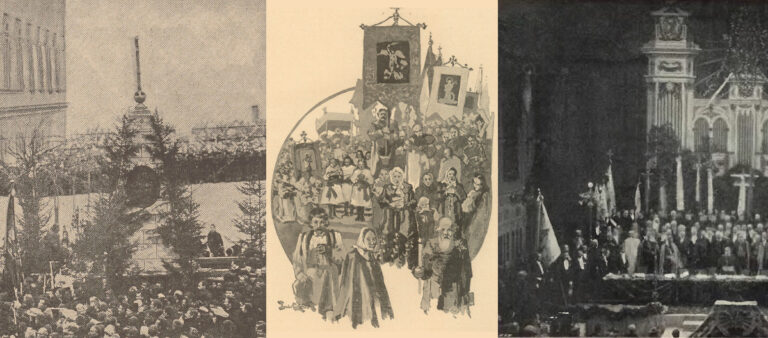

Religious rituals are one of the few types of mass demonstrations allowed after the suppression of the Spring of Nations. Like imperial visits, they became a source of "inspiration" for political activists. During church celebrations, it was not difficult to combine what was necessary (religious elements allowed by the authorities) with what was desired (national elements). After all, in Galicia belonging to a certain denomination almost always defined national affiliation as well.

The calendar difference separated the "Polish" and "Ruthenian" religious holidays in time, the Jewish calendar not coinciding with either of the previous two. Accordingly, "Ruthenian Theophany" or "Polish Corpus Christi" were legal national manifestations long before classical national manifestations became allowed.

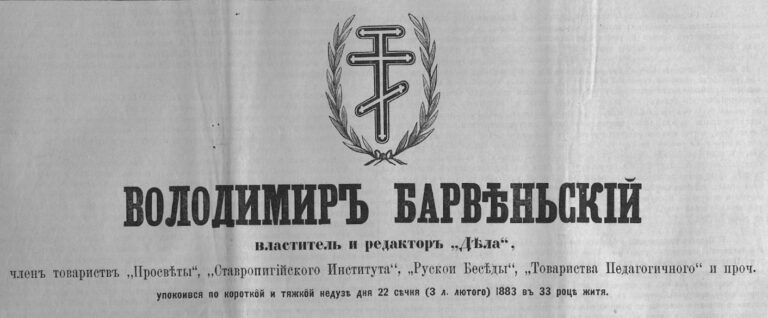

It was the same with funerals combining a religious ritual with a kind of manifestation, where national affiliation, participation in political projects, and status were clearly followed. Through the funeral, the deceased symbolically acquired immortality, which was later confirmed by the installation of a monument.

Urban history

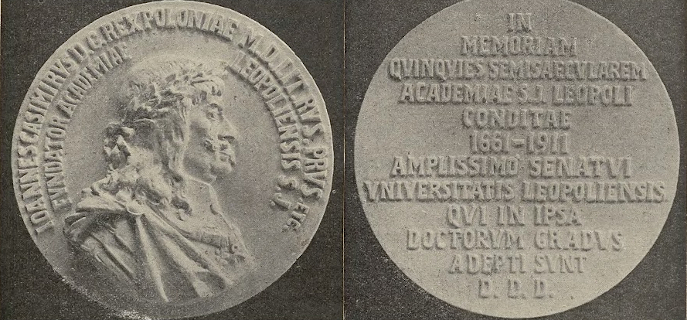

In addition to being part of the empire and the capital of a crown land, Lviv also had its own history, its own "masters of the city", as well as population groups that considered the city the center of their own national projects. During the times of liberalization and autonomy, urban elites and authorities celebrated not only national anniversaries but also events from purely urban history, thus presenting this city in a favourable (for them) light.

The Poles emphasized the bourgeois traditions of the "royal city" and the "democratic" heritage of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. They also never forgot to remind that the successes achieved during the times of autonomy were part of the success of the "development of Polish society", in Lviv personified by the City Council. The Ukrainians appealed to the heritage of ancient Rus, the seat of the Greek-Catholic metropolitans and the "capital of Prince Leo."

Space marking

The second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century were the time when monuments, sculptures, commemorative plaques and even individual buildings were erected and installed with the intention to immediately "tell" whose city this was and what its history was. Massive renaming of streets and squares should also be mentioned. All this can be described as space marking.

Polish politicians who held the power in Lviv, obviously, took full advantage of it during the period of autonomy. This means that urban toponymy worked for the Polish national project. The Ukrainians and Jews could be at most "present" in "Polish Lviv", mainly in their national enclaves such as institutions, churches (synagogues) or neighborhoods. The presence of the empire on the city’s façades or in the city’s names was also very limited, compared to the presence of the Polish national project.

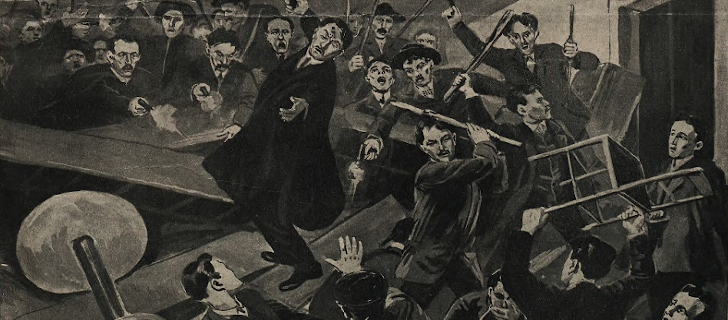

In times when politics literally "went to the streets", this played a huge role, enabling Polish patriots to hold rallies near the monument to Mickiewicz instead of the Ferdinand-platz.

Welcoming guests

In addition to the emperor's visits, Lviv also welcomed various other guests. As in the case of the press (which was a way to convey one's opinion to an audience outside the city and therefore to present one's political or national group as the whole "city"), these visits were an opportunity to present oneself externally, to tell about oneself (and therefore about one's national project) to the world.

Here, too, the situation was similar: the Poles could invite "to Lviv" and organize rituals that accompanied the emperor's visits, whereas the Ukrainians or Jews invited guests to "visit them in Lviv." As a result, the Poles demonstrated "their city", while the Ukrainians and Jews demonstrated "themselves in the city." At the same time, neither the Poles nor the Ukrainians considered each other as equal partners in the long term, as they talked about their exclusive rights to this territory. This, after all, found its expression after the First World War.

* * *

In the end, whatever it was about — imperial visits, religious rituals, reception of guests or public space — sooner or later it came down to the national question. Between the city and the empire, there were nations that claimed this city.