In 1878, after the end of another Russo-Turkish war and as a result of agreements concluded at the Berlin Congress, Austria-Hungary occupied Bosnia and Herzegovina. The major European powers took this step to prevent Russia from increasing its influence in the Balkans and creating a powerful pro-Russian state there.

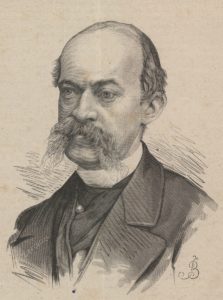

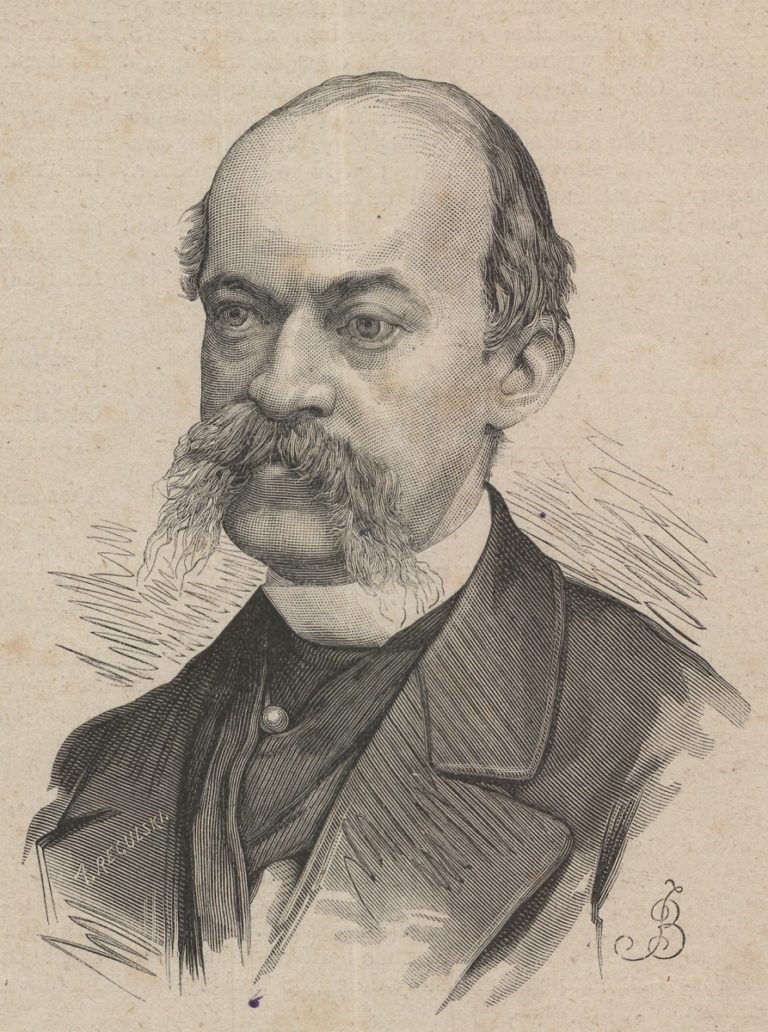

Otto Hausner, a member of the Austrian parliament born in Brody, became widely known for his speeches against this occupation. He supported the Slavs of the region in opposition to Vienna's Germanization policy. Obviously, it was not only and not so much about protecting Serbs and Bosnians, but also about the situation of Poles in Galicia.

No wonder so that in November 1878 Otto Hausner was greeted in Lviv as a hero, a brave oppositionist and a defender of national interests. On 9 November 1878, the City Council considered a proposal to grant Otto Hausner the title of honorary citizen of Lviv. The majority was clearly in favour and the decision was passed, but when it came to voting, the chairman of the meeting resigned his position. The obvious reason was fear of the authorities, which, however, was masked by concern for Polish members of parliament and the upcoming negotiations on the autonomy of the province.

The banquet

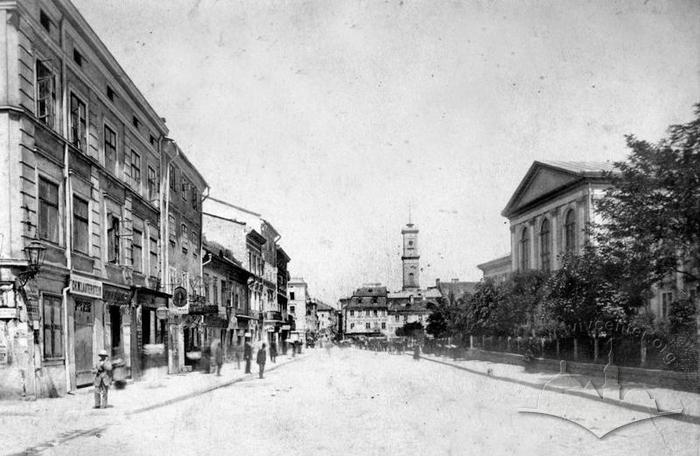

On Saturday, 16 November, a gathering for more than 200 persons was organized in the City Casino on ul. Akademicka, called a "banquet." Actually, it was a textbook example of a "political banquet", where speeches were made and agitation was carried out under the guise of toasts and congratulations.

Many of the participants, who were mostly wealthy people interested in politics, came from the province. The tables were arranged in a horseshoe shape, so that the center of the horseshoe was in the place where a podium is usually placed.

The event started at 9 p.m. There were five "toasts" in total, promoting love for the homeland, defence of Polish interests in the face of centralism, and support for the Polish cause by other peoples of the empire. And, of course, there was Otto Hausner's own "toast", in which he described his political position for several dozen minutes.

The extent to which this banquet was a banquet in the usual sense of the word can be judged even by the fact that various societies sent congratulatory telegrammes full of patriotic rhetoric to the participants of the event.

Clashes with the police

To honour Otto Hausner, Lviv youth decided to organize a torchlight procession, something that had only been done before in honour of the Emperor's visit. The police rejected the organizers' application, but they appealed to the governor and the government. The wording used by the police to justify the ban was interesting: Hausner's opponents could have taken to the streets as well, and therefore, a conflict could have arisen. The march organizers reasonably asked what was the point of constitutional amendments and legislation on freedom of assembly if they could not be implemented because there were opponents and the threat of clashes. This episode makes it clear how different the pace of reforms perception was between society and the state apparatus.

On the eve of the march, a telegram appeared in a Lviv newspaper announcing that the ministry had cancelled the police ban. This message encouraged some young people to go on the march rather than wait for written permission from the police.

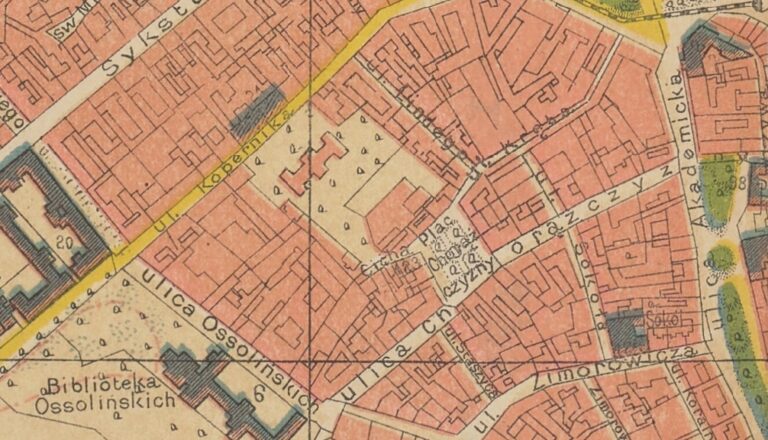

The students gathered on pl. Św. Jura and headed for the city, lighting torches along the way. From the City Garden, they were attacked by policemen and police agents in civilian clothes. The students then split into two groups, bypassing the park. In the process, random passers-by began to join them.

Through ul. Ossolińskich, ul. Chorąszczyzny and ul. Zymorowicza, the marchers made their way to ul. Akademicka, which had been full of police and agents since 7 p.m. Some newspapers reported that police agents marked with white tags specific passers-by, who later suffered particularly from the police. In total, several thousand people had already gathered there, chiefly in front of the illuminated casino building.

At 9 p.m., the march from pl. Św. Jura approached ul. Akademicka. Several participants of the "banquet" went down to greet the youth. The first person they saw was, however, a police commissioner with a bloody sabre in his hand. He was just running away from the crowd into the casino when he was hit in the head with a stick and fell down in the gate. The police mercilessly dispersed the demonstrators, throwing them down to the Poltva river, shooting and slashing them with sabres. Some policemen reached as far as pl. Mariacki, where a fight burst out between police and military officers who were walking in the city center with their wives.

Nevertheless, the students managed to shout greetings to Otto Hausner before the police pushed them back to the George Hotel. The "banquet" invitees were beaten on the bridge over the Poltva river even at midnight, when they were leaving the casino.

During this time, some City Council members tried to meet with the police director — to no avail, though. Only deputies were present at the police station, who continuously received complaints from citizens who had been beaten and injured with cold steel. On the same day, ten detainees were transferred to the court, where a rally also gathered outside the building, though without any confrontation. Until 1:30 a.m., an infantry unit was stationed outside the guardhouse, but it was never called in.

The incident description in the government-run newspaper Gazeta Lwowska was identical in terms of facts, but completely different in terms of assessment. In the end, this continued throughout the entire period of autonomy. According to this version, "certain individuals" incited young people to organize a torchlight procession in honour of Hausner, despite a clear police ban. On the way, the protesters beat a police commissioner who reminded the participants of this ban and eventually convinced some of the students to disperse.

Another police commissioner was beaten on ul. Akademicka when he, again, called on young people not to break the law. Only when stones and bricks flew at the police did the police use force. At the same time, four police officers were seriously injured and eight were slightly injured. Out of eighteen detained demonstrators, eight were released immediately, while only ten were handed over to the court.

Consequences and interpretation

In general, it is difficult to assess both the course and public opinion around the event, as most of the newspaper articles dealing with the topic were simply cut out by censors.

On Monday, an emergency meeting of the City Council was held. The council members condemned the actions of the police and appealed to Vienna and to the prosecutor's office. Most importantly, they asked for a clearer definition of the difference between a police officer and a civilian, as plainclothes police agents caused the most stir during the clashes.

Governmental and non-governmental newspapers searched for examples of condemnation or approval of police actions in the press from outside Lviv and presented this as an argument. For example, Hausner was accused of involving young people in a political struggle when he could have called for restraint if he had taken pity on the students. This led to the idea that it was bad to "involve young people in politics." Patriotic Polish newspapers wrote that the titushky hired by the police spoke Jewish jargon and that every 15 years, there was a revolution in Poland.

The example of the clashes between Polish youth and the police in 1878 shows society taking its first steps in a new, more liberal environment while the police continued to act in the old way. Politicians, mechanically, convened a "banquet" rather than an assembly or a rally (although the law already allowed it). In the meantime, newspapers became the mouthpiece of their respective communities.