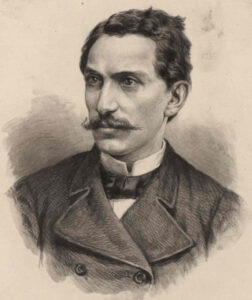

Volodymyr Barvinskyi was an ideologue of the populist movement, a writer and the founder and editor of the "Dilo" newspaper. His death and funeral in 1883 marked the beginning of the formation of the Ukrainian national pantheon at the Lychakivsky cemetery.

In the national movement, Volodymyr Barvinskyi was an extremely influential and very symbolic figure, given his full dedication to social activities, weak health due to a childhood injury, death at the age of 33 — the "age of Christ", as well as The Cut Blossom, a novel written by him whose title seemed to resonate with the death of the author himself. Therefore, regardless of his dying wish to be buried in his native village, Shliakhtyntsy in what is now the Ternopil oblast, it was decided to include him in the national pantheon, which the Ukrainians were just beginning to form in Lviv at that time.

His funeral became an event of almost the same importance as the First All-People's Assembly organized by him in 1880. Ivan Franko wrote about this as follows: "His funeral became a great manifestation of the entire Ruthenian people. At his fresh grave, the Ruthenians felt like brothers, they forgot about everything that divided them, and the tears that fell on his deathbed were the first clean tears of brotherly love..."

The newspaper "Dilo" published letters from all over the province like this one: "Our father is gone, the sincere and tireless defender of our rights is gone, the heart that loved his people so much is gone!"

The course of events

At 15:00 on February 5, 1883, thousands of people gathered near the residence of the deceased on Halicka Street (now Kniazia Romana 24 Street). The public was mainly from Lviv: apart from "friends from all over Ruthenia" without any clarifications, the newspapers reported mostly about "Lvivians" and "the clergy from the Lviv suburbs." Apparently, during the time between the death on February 3 and the funeral on February 5, it was impossible to gather villagers like for an assembly.

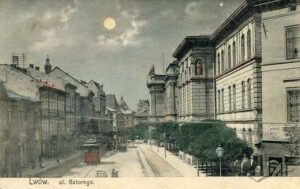

Kniazia Romana Street on a postcard from the early 20th century. On the left, building No. 24 can be seen, where Volodymyr Barvinskyi lived. In 1883, there was no tram running down the street, and the depicted building of the Provincial Court had not yet been erected.

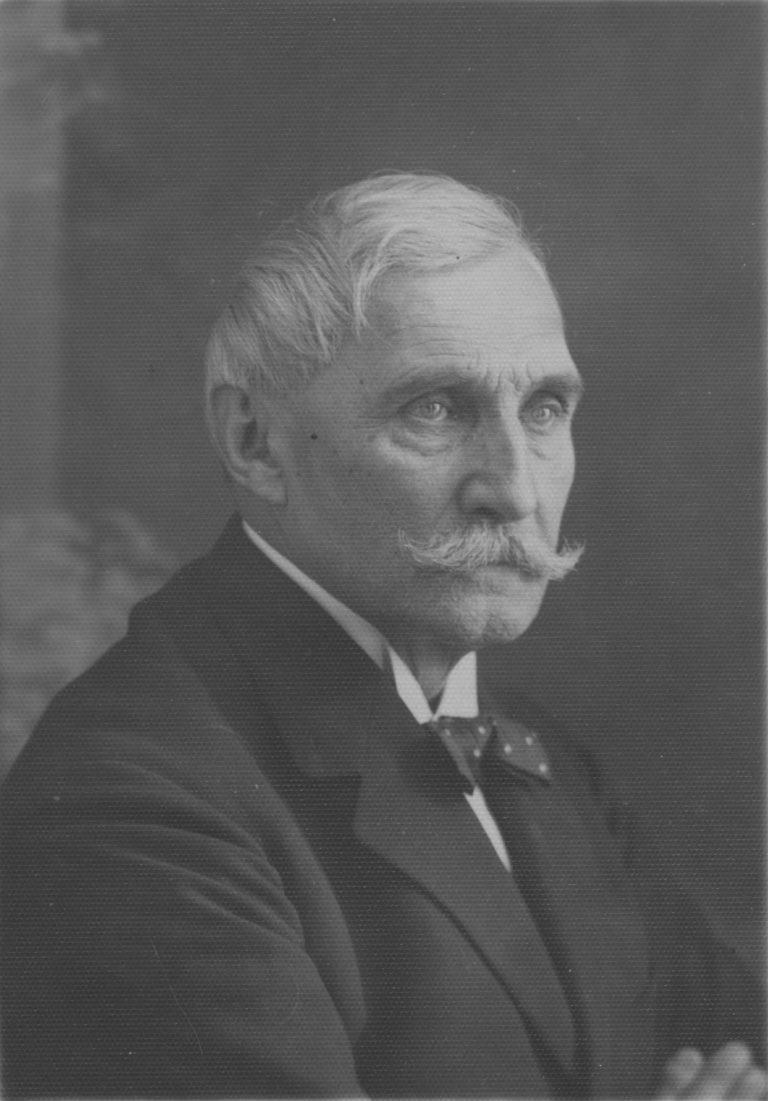

Newspapers emphasized the participation of the clergy, who, so to speak, played the role of the aristocracy. The memorial service was conducted by Bishop Sylvester Sembratovych, who actually headed the Metropolitanate of Halych at that time, while the choir of the Greek Catholic seminary was singing. Anatol Vakhnianyn, one of the populist movement leaders, gave a speech mentioning the deceased’s merits, accomplishments and role. He also added that the latter’s "eyes were covered with red silk cloth, a Cossack merit", the fact showing the influence of the Cossack myth on the formation of the ideology of the Ukrainian movement in Galicia (see details, Zayarnyuk, 2005).

Due to health problems, Bishop Sembratovych did not lead the procession to the cemetery and transferred his powers to Fr. Omelian Petrushevych. Members of the Stauropegion brotherhood marched with their banners. Seemingly, the presence of Russophiles was the reason for Franko to call Volodymyr Barvinskyi's funeral an act of unity of the Galician Ukrainians. Representatives of societies and newspaper editorial offices carried wreaths, including several with inscriptions in Polish. Even considering the list of wreaths, it is clear that the funeral turned out to be an event attended mostly by townspeople and not by peasants, like most Ukrainian manifestations in Lviv at that time.

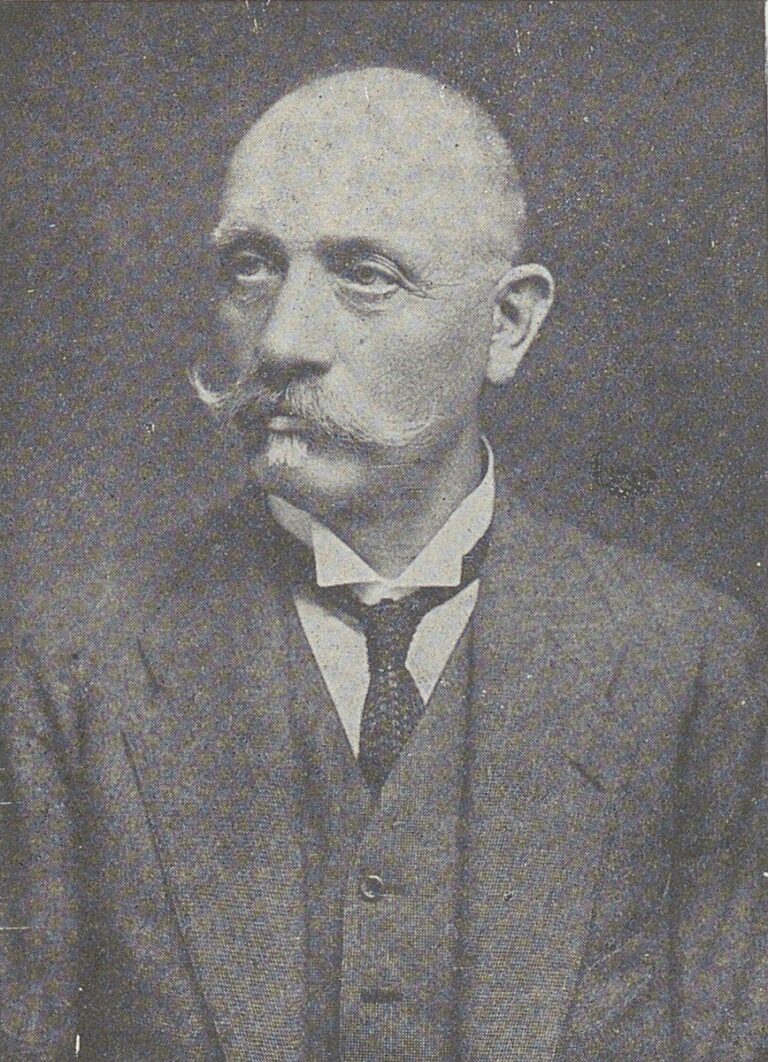

Later, the new editor of the "Dilo", Antin Horbachevsky, carried the last issue of the newspaper published under the leadership of Volodymyr Barvinskyi on a "gold-woven silk pillow." He was followed by the choir, clergymen, young people carrying the coffin in their arms (which was considered a great honour), family and other participants of the funeral. A human corridor along the route was mainly formed by students. The procession appeared to be "sad and magnificent", as "Ruthenia was burying her Son and Guide."

After the memorial service, speeches were read at the cemetery, two in Polish (from the burgomaster of the town of Rozdil and the editor of the Sztandar magazine) and three in Ukrainian. Moreover, the latter included words about a "faithful son of the people and the church" and a quote from Shevchenko (who was not well tolerated by the church at that time): "My brothers, hug the youngest brother" (see details, Kis, 2015).

Monument

The tombstone monument for which money had been collected for a long time and which was installed in 1892, was filled with meanings that were key to the national project of that time. There were the genius of Ruthenia in the form of a female figure (originally, an angel was conceived), a torch as a sign of enlightenment, a cross as a testimony of faith, an olive wreath as a symbol of peace, as well as the young generation in the form of a boy wearing an embroidered shirt.

In 1892, however, not a trace remained of the unity between the Russophiles and the populists, so both groups celebrated the anniversaries of Volodymyr Barvinskyi separately. The populists commemorated him in the Basilian nuns' church, while the Russophiles did the same in the People's House.

In February 1892, the sculptor Stanisław Lewandowski exhibited a plaster model of the monument, which he had been making since 1889, in the premises of the industrial school on ul. Teatralna. For a small fee, visitors could look at the project; the proceeds were intended to cover the cost of transporting the monument. It was installed some time in 1892 (Biriulow, 2007, 131).

In 1892, the "Dilo" devoted much more attention to the installation of a monument to Taras Shevchenko in Vynnyky and to the reburial of Markiyan Shashkevych, which was planned for the following year. Barvinskyi's grave became the first object of the Ukrainian pantheon in Lviv.

The funeral of Volodymyr Barvinskyi is an interesting evidence of the beginnings of Ukrainian mass politics in Galicia. The formation of the national pantheon began at a time when the position of the church was extremely strong, when the cult of Shevchenko and the Cossack myth were just beginning to develop, and disputes between Russophiles and Ukrainophiles were considered party differences. At that time, Ukrainian-Polish relations had not yet intensified to the level of the early 20th century.