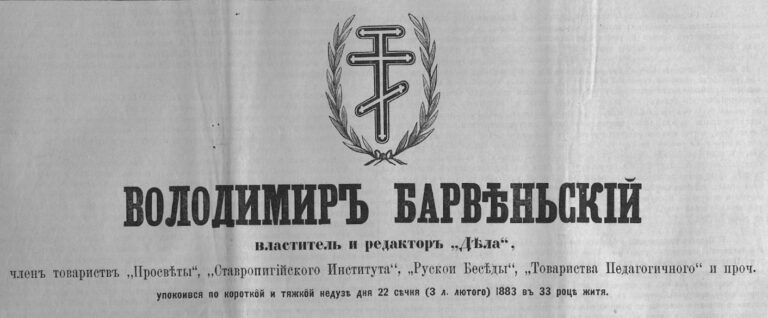

The reburial of Markiyan Shashkevych in Lviv on November 1, 1893 is considered one of the most significant "national manifestations" of the Ruthenians in the city. Apart from the mass character of the event, the figure of the poet himself as a "people's awakener" is important, by analogy with national poets of other nations. Also, the fact of burial at the Lychakivsky cemetery showed the continuation of the formation of the Ukrainian "national pantheon" alongside the Polish one.

The reburial of a poet's ashes was not a unique case. The Ruthenians of Galicia could take an example from both the ceremony of transporting the body of Taras Shevchenko to Kaniv in 1861 and the body of Adam Mickiewicz to Krakow in 1890. It should be remembered that Markiyan Shashkevych was not only a poet and "awakener" but also a Greek Catholic priest. This explains the participation of not only political activists but also numerous representatives of the clergy.

The state of Ukrainian-Polish relations at that time, namely the implementation of the New Era policy, was favourable for events of this kind. In the same way, the person of Shashkevych, a poet and a priest, allowed to demonstrate the unity of Ruthenian politicians and the hierarchy of the Greek Catholic Church.

The initiator of the reburial was the Prosvita Society, and the event itself was timed to the 50th anniversary of the death of Markiyan Shashkevych, who died on June 7, 1843. The date of November 1 was chosen because it was a day off (All Souls Day, when deceased relatives' graves were visited), in order to gather a larger number of participants from outside Lviv.

Course of events

The poet's body, after being exhumed and placed in a zinc coffin, was first transported from the village of Novosilky (now the Lviv oblast) to the railway station in the village of Zadvirya. The procession itself was not inferior to the later procession in Lviv. There was a so-called banderia consisting of 80 young men on horses with blue-and-yellow flags and wreaths, church brotherhoods, clergy and peasants from the surrounding counties. More than forty peasant carts alone were used. The coffin was decorated with a wreath with blue and yellow ribbons.

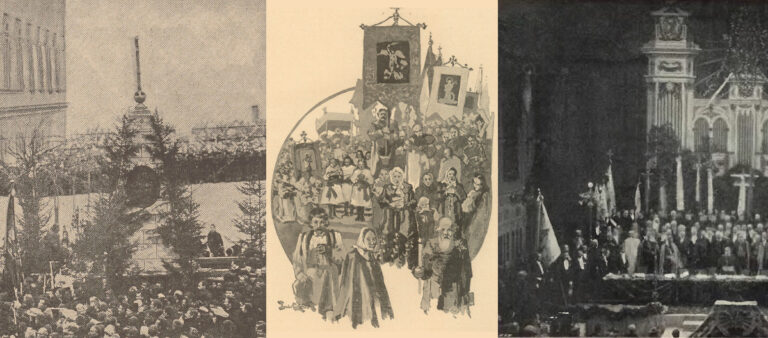

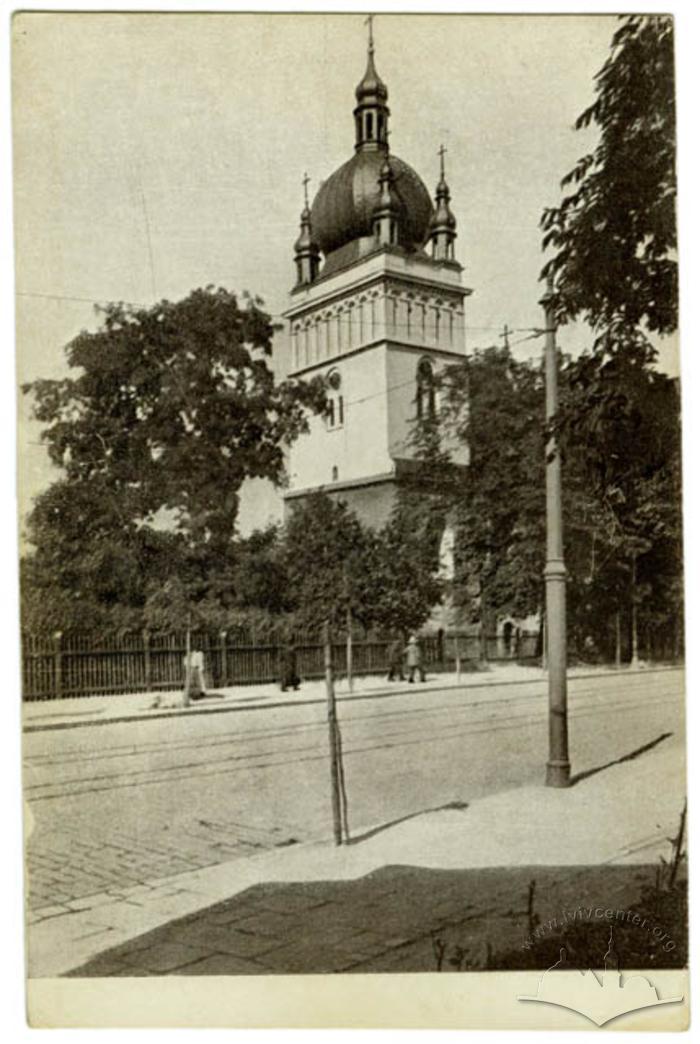

At 10:00, the train with the poet's ashes arrived at the Pidzamche station. At the same time in the church of St. Paraskeva, a memorial service was held, attended, in addition to the arriving peasants and the Ruthenian intelligentsia, also by a few representatives of the authorities (the president of the city of Lviv, Edmund Mochnacki, demonstratively, through the press, invited all members of the City Council to participate in the event).

Several thousand people gathered on the square opposite the railway station. The hearse (as during the transportation from the grave to the train) was arranged like a "peasant cart" pulled by three pairs of oxen decorated with green branches. The oxen were driven by Hutsuls in traditional costumes. After a short mourning service led by Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych and with the participation of the choir of the Lviv Theological Seminary, the leader of the Prosvita Society, Fr. Omelian Ohonovskyi, and the Metropolitan himself gave their speeches.

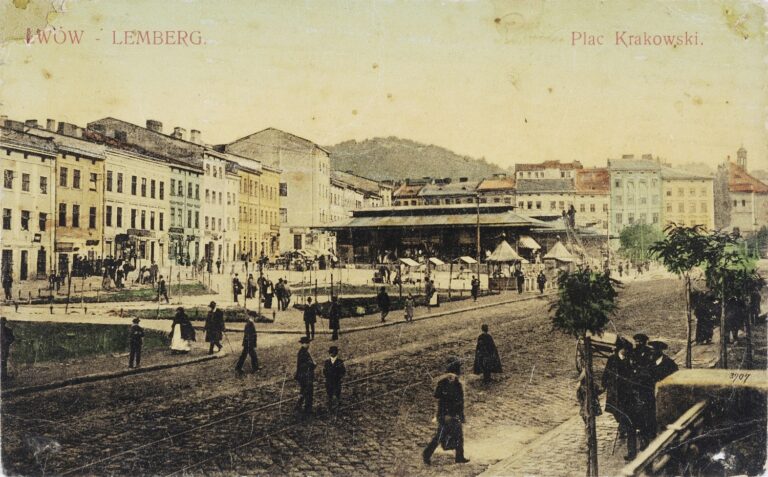

After that, the procession went to the Lychakivsky cemetery along the following route: Żółkiewska Street, Krakowski Square, Teatralna Street, Mariacki Square, Halicki Square, Bernardyński Square, Piekarska Street. As was customary in cases like this, the order of movement was determined earlier. The column was headed by representatives of church brotherhoods with their banners, then schoolchildren and gymnasium youth, students, delegations of villagers and reading houses (both rural and urban, for example, from Drohobych, Sambir, Kalush). They were followed by members of the craft society Zoria, other organizations like the academic societies Kruzhok and Bratstvo, the Dnister, the Narodna Torhovlia, the Ruska Rada, the Narodna Volia, the Narodna Rada, the Pedagogical Society, the Prosvita Society, the Stauropegion Institute, seminarians, the clergy headed by the metropolitan. In the middle of the column, the hearse was moving, surrounded by an honour guard consisting of students with special signs — red ribbons (these were members of the Student Society Vatra). Behind the hearse, there were Markiyan Shashkevych's family, the president of the city Mochnacki with "a group of representatives" of the City Council and other members of the public. Thus, there were no representatives of the Provincial Department or the governor's office at the event.

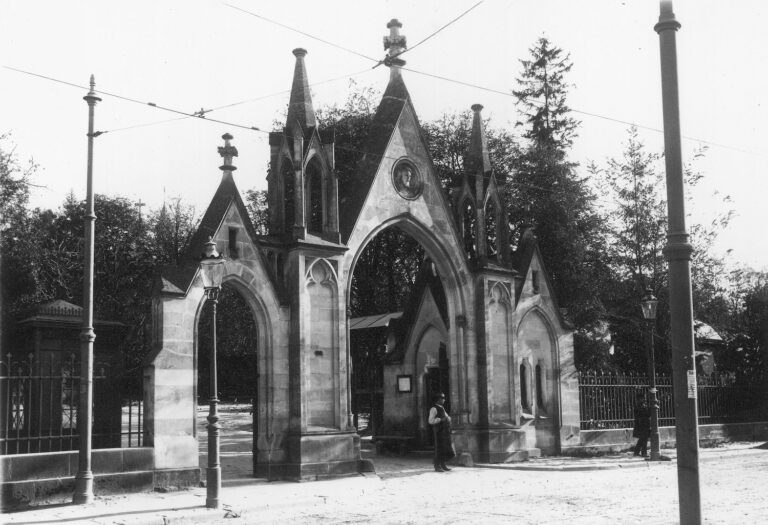

The march lasted from 11:00 till 13:00, when the procession reached the entrance to the Lychakivsky cemetery. Here, the coffin with the body of Markiyan Shashkevych was removed from the cart, and priests carried it to the burial place. After another memorial service and the laying of wreaths (from each of the mentioned groups of participants in the procession), short speeches were made by one of the priests and by Yulian Romanchuk, a member of the Austrian Parliament and the Galician Diet (Sejm), the head of its Ruthenian Club (faction).

During the march, order was maintained by members of the "civil guard", which in this case consisted of students and villagers, in contrast to the Polish events, when the "guard" was recruited from the "citizens of the city."

In the evening, on the occasion of the reburial and the 50th anniversary of the death of Markiyan Shashkevych, a solemn concert was held in the People's House with the participation of the outstanding opera singer Oleksandr Myshuha. In addition, around forty telegrams were read to the audience, with one "from Polish youth of Warsaw" among them.

Interpretation and meaning of the event

For Ukrainian politicians, the event had huge symbolic significance. For example, Kost Levytskyi wrote about "Markiyan's triumphal entry into the capital of the Galician Land." The unification of Ruthenian society around the figure of the poet, when "there was no longer any gap between the people and their leader", was also mentioned.

Taking into account the need for a mass Ruthenian "presentation" in Lviv, it was not accidentally that the date of November 1 was chosen, since it was a day off, when many villagers could be involved in the demonstration.

Nevertheless, despite the apparent harmony, there were also contradictions within the political community. During the march in Lviv, activists distributed a separate "proclamation", printed on a single sheet, where the persecution of Shashkevych by the Greek Catholic hierarchy was mentioned. In this proclamation, the contemporary hierarchs were urged not to repeat the mistakes of the past and not to persecute dissidents.

Another interpretation can be found in the Polish press. Instead of describing the mass character and solemnity, the Polish Democrats said that the ceremony "was excellent, though very modest." The government-run Gazeta Lwowska reported that "passers-by had been moved by the simplicity of the ceremony itself." Although, objectively, there was little reason for such an assessment (except for the hearse in the form of a peasant cart). The procession with the body of Markiyan Shashkevych looked like an ordinary mass funeral procession of those times, with all the necessary attributes.

The little attention paid to the events of November 1 by the Polish press can be explained by the fact that on the very following day, November 2, the Poles of Lviv celebrated the 99th anniversary of the "Massacre in Praga" (a suburb of Warsaw stormed by Russian troops under the leadership of Alexander Suvorov on November 4, 1794) and the 45th anniversary of the bombing of Lviv during the Spring of Nations. In this context, the reburial of a "rural" poet was really not as noticeable as in the Ukrainian press.

After all, the reburial was the beginning of the cult of Markiyan Shashkevych in Galicia. He became a symbol of the struggle for national rights and a "people's awakener", and an example of the resistance of the "lower classes", because during his life he was subjected to repressions by the secular and spiritual authorities of his time.