"In our national and social life, there was not a single important event to which Lviv would not immediately react. Whether it is about the eastern or western border, about politics or the national economy, Lviv is the first to signal for struggle or defense. These slogans are by no means monopolized by any single party or group. On the contrary, they are all more or less viable, because they grow in a life-giving atmosphere".

"Żywotność Lwowa", Kurjer Lwowski, 1912, Nr. 227, s. 1

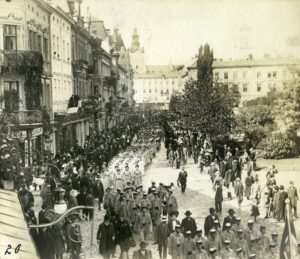

During the 19th century in Europe, a new phenomenon called mass politics emerged alongside the process of democratization. Politics increasingly moved from governmental offices and parliament halls to the streets and squares of cities, and meetings on the premises of various societies were gradually replaced by open street demonstrations.

Being the political center of Austrian Galicia, Lviv was no exception. Key institutions such as the sejm (parliament), the governorship, and the university operated in the city. Political and national confrontations were concentrated here. The "Royal Capital City" of the crown land was considered at the same time the "capital of the freest part of Poland" and the ancient "capital of Ruthenian Prince Lev." Although the population of Lviv at that time consisted of Poles (52%), Jews (30%), and only then Ukrainians (18%), the competition between Ukrainians and Poles was the most significant. They declared their exclusive rights to the city and province as fundamental to their own national projects.

Both Poles and Ukrainians enjoyed all available political freedoms. The Austro-Hungarian Empire during the late 19th to early 20th century was a monarchy where competition between political parties and national projects existed. This competition became possible after the introduction of the 1867 constitution and subsequent liberal reforms. Practices of political mobilization from Western Europe were adopted, and customary religious and imperial public rituals were adapted to the new needs of modern mass politics.

During the period of autonomy, the "street" became a significant factor in political life. What mattered was not only how many voters would support a specific politician, but also how many people that politician could bring out to a rally or demonstration. The more radical the demands of the "street" became, the more radical statements politicians had to make. This mutual radicalization, fueled by political competition, eventually led to the militarization of youth societies and a "readiness to fight," which was declared by almost all public associations, from political parties to professional clubs.

Mass Events in the Urban Space

This project focuses on events in the public space of the city, under the open sky. Significantly more events—ranging from city-wide patriotic concerts to gatherings of waitstaff—were held in indoor venues, such as halls or theaters, until the end of the empire. However, "street" actions were more conspicuous. Going out into the streets to express one's opinion without it automatically being considered a rebellion was still a novelty.

After the suppression of the "Spring of Nations" in 1848 and until the adoption of the 1867 constitution, the only legal avenues for public expression were religious rituals and imperial celebrations. Local elites and patriots tried to showcase themselves, their city, and their region within "permissible" boundaries. With the adoption of the constitution, people began taking to the streets under national, and later social, slogans.

This is reflected in the project's structure, where texts are grouped into major sections that demonstrate the city within the empire, the national city, and the social city.

This doesn't mean that there was a clear boundary between the national, social, and imperial aspects. Everything was intertwined, and when the successes of Lviv as a city were shown to the emperor, he was shown the successes of the Polish administration. When socialists organized a rally in solidarity with workers in the Russian Empire, they stood in solidarity with the Polish workers. So, in each text, conflicts can be present at various levels: between workers and employers, between the right and the left, between Ukrainians and Poles, between the national project and imperial power.

On the other hand, the section dedicated to events during the Great War is at the same time concluding. It aims to show the ultimate results of the political activities of local activists and how the national aspect prevailed over the social and imperial ones. This is well illustrated by a quote from a Lviv democratic newspaper at the beginning of the war in 1914: under those conditions, "we must work exclusively for the homeland, and replace the red flags with national ones."

Organizers of most events described in the project drew inspiration from existing practices of mass gatherings, primarily from church rituals and imperial court ceremonies. These were supplemented with examples of street demonstrations in Western European countries. Based on this foundation, local activists developed their own political activities.

Over time, the format of these events changed. Initially “viches” were common as gatherings of activists where each participant could be registered and controlled. Then political demonstrations and rallies gained popularity, where individuals could get lost in the crowd. The format of the meetings changed, but the term “viche” came to be used for both types of events: chamber and mass gatherings. This, in turn, meant that participation in politics could be anonymous, and participants could behave more radically and less law-abiding. Participants in the viche held at the People's House, especially delegates, also in the presence of the commissar of the police, couldn't afford to shout slogans like "Let's finish what Khmelnytsky didn't have time for." However, participants in mass gatherings, especially on the streets, could.

The city's space had a significant influence on these processes. The project mentions architecture, spatial markings such as monuments or symbolism of specific places. However, the main focus is on how the space became a site of communication: how the authorities "spoke" to the citizens in it, and how the citizens, in turn, could address the authorities. Additionally, the project explores how local elites gained power and how they utilized this space. While the emperor could greet the citizens from the governor's palace balcony, protesters could gather under the same balcony to express discontent toward the visiting prime minister.

However, it's important not to mechanically project contemporary notions of protests onto events from that time. For instance, the concept of human rights was different, which influenced police actions. The use of swords (referred to as "white arms") against protesters wasn't extraordinary, but firing into the crowd could lead to official inquiries. The unrestricted circulation of firearms had an even stronger impact, and for this reason student demonstrations with the use of revolvers were not uncommon. The term "emancipation" referred to a process with an uncertain outcome.

Mounted police near the building of the Galician Sejm during demonstrations for universal suffrage in 1908

City expansion, population growth, and political changes led to a reimagining of Lviv's geography. New locations emerged, and existing ones were repurposed. For instance, Ferdinand Square, where a triumphal arch was erected for the meeting of the young Franz Joseph in 1851, later became a key gathering place for Polish nationalists and socialists – "under the Mickiewicz monument." Familiar gathering spots for workers, such as Szajnochy Street (modern-day Bankova), or for students (near the Polytechnic) stood out. Near the Mickiewicz monument, the Municipal Theater was established, providing a convenient venue for rallies, making Rynok Square a less popular place for demonstrations. Lychakiv Cemetery, the Sokół stadiums, Execution Mount, and even the Devil's Rocks near Vynnyky became places of political pilgrimage.

The Government and the Role of the "Street"

As a result of liberal changes in the empire, in the 1860s political power in Galicia was obtained by Polish landowners. The changes in local governance were seen as a green light for the development of a national community. The Polish language became official, effectively displacing German. Political environments were formed in cities that were either predominantly Polish or oriented toward the Polish national project.

Greetings of Emperor Franz Joseph I at the Lviv railway station (1888). Source: National Museum in Krakow

The image of a "democratic city" (or, in the words of conservatives, a "hotbed of socialism") became associated with Lviv, contrasting with Kraków, where more conservative provincial gentry dominated politics. Although the elections in Lviv at that time cannot be considered exemplary democratic due to many property and legal restrictions on those who could vote or be elected, they did not follow a curial system.

This "freedom and democracy" immediately began to function in a Polish national context, manifesting in the renaming of streets and the replacement of street signs, the installation of monuments, and the organization of various assemblies. Galicia, as an Austrian province, ceased to be in opposition to the "Fatherland."

The position of Ukrainians in Lviv was much more modest. In theory, they could claim a proportionate number of mandates in the City Council. In practice, at the beginning of the 20th century, Ukrainians entered the council more often as part of the "general urban candidate list," as very few voters voted for the "national list." In such a situation, there was no need to discuss any separate Ukrainian policy in the City Council. The Sejm and the governorship were not particularly pro-Ukrainian either, so the Lviv "street" was a place where Ukrainians could assert themselves not only at the city level but also at the regional level.

Akademicka Street, modern-day Shevchenko Avenue during the 1911 overthrow of the Ukrainian Sokil. Photo from the collection of Stepan Haiduchok

Participation in local self-governance gave Poles opportunities for "major politics." For instance, it allowed them to financially contribute to the restoration of the Wawel Royal Castle in Kraków or as "city proprietors" to speak before the government to oppose the establishment of a Ukrainian university in Lviv. Or to finance construction projects like the City Theater, which essentially were national projects.

The influence of the "street" made itself felt, and populists tried to tap into national sentiments more and more. During the 1911 election campaign, there were discussions about the "threat to Polishness in the capital of the region," which came from the "Germanizers, Zionists, and descendants of Khmelnytsky."

Therefore, the "street" is a crucial concept for the processes described in the project. On the eve of the Great War, the press claimed that the influence of so-called street politics was a distinctive feature of Lviv, thanks to which the city took second place in "pan-Polish politics," behind only Warsaw. In such circumstances, when the street became a political factor, it became important not only who was elected to parliament, but also how many people a politician could mobilize for demonstrations. This, in turn, provided an opportunity to influence Vienna—not only for Poles but also for Ukrainians, who were largely deprived of traditional instruments of influence. Striking examples include the torchlight processions during the time of Franciszek Smolka, demonstrations regarding the separation of the Chełm region from the Kingdom of Poland, and the actions of Ukrainians against the policies of Prime Minister Ernest von Koerber.

Confrontation throughout History

Another area of conflict was the interpretation of history: those who held power in the city and the region in the past were considered to have the right to write history. Poles considered the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth as the "Golden Age," and thanks to the democratic Constitution of May 3, socialists were not an exception here. The arrival of the Austrians in 1772 was seen by them as an occupation, while Ukrainians and Jews perceived it as liberation and the beginning of emancipation.

Due to its autonomy, Lviv became a center of Polish historical politics. Victories like the Battle of Grunwald were commemorated here, and a "national anti-German viche" was held in 1903. Thanks to liberal legislation, Ukrainians could also honor their history, for instance, by celebrating the centenary of Markiyan Shashkevych in 1911 or Taras Shevchenko in 1914. However, there were also instances of overtly conflict-prone situations. The year 1905, among other things, marked Poles celebrating the anniversary of Lviv's rescue from Bohdan Khmelnytsky's Cossacks, while Ukrainians held a viche at the same time, after which some participants decided to march to the town hall and express their opinions to the “lords” on the matter. Therefore, when the Polish press mentioned "haidamaky," it was not just a literary device; often, it reflected the real confrontation between Ukrainians and Poles, evidence of a threat to the "Polish state of possession."

Lviv was losing to Kraków in the "historical" dimension. Since it lacked a royal castle and burials of prominent historical figures, Lviv emphasized the history of its bourgeoisie — ultimately, an advantage in the era of growing bourgeois influence. The "historical map" was also played out in the realm of the governorship, for instance, commemorating the anniversary of the victory of the "Austrian arms" over Napoleon.

Contrasting the City and the Village

There were objective reasons to sense this threat – Ukrainians often described Lviv as a Polish enclave in a "Ruthenian sea." On the other hand, Ukrainians could not often hold any significant demonstrations in the city without the involvement of villagers. They had to be mobilized in the province with the help of the Greek Catholic clergy. Therefore, when it came to the national confrontation with Poles, Ukrainians fought mainly not in Lviv, but for Lviv. For the "ancient capital of Prince Lev," in which it was necessary to gather – a kind of political pilgrimage.

For Poles, however, Lviv was a dynamic environment of a modern nation as opposed to the rural patriotism of the old elites, whose political activity revolved around their ancestral estates. Not an ancient, but a contemporary capital, the main city of the "united free part of Poland." Such positioning imposed certain obligations and also made Lviv a center for Polish emigrants from the Russian Empire and Germany. The understanding that around the "Polish city" there was a "Ruthenian sea" compelled the Polish press to emphasize every event where Polish peasants were involved – from rural theater society gatherings to the arrival of rural branches of the Sokół organization. After all, presence in the villages confirmed the "right to land" and thus to the region, not just the city.

However, from a patriot's perspective, until the mid-19th century, there was nothing for a "decent man" to do in the city. First, in the cities there were no "people" in the popular romantic understanding at that time. Second, the city "corrupted" people. Over time, this changed, and Lviv began to be regarded by Poles not only as a "Polish fortress on the frontier" but also as a center of democratic movements (in contrast to the "conservative" Kraków), a city whose "streets" set the tone for the rest of Poland.

The notion that the city had a negative influence on the "people" persisted much longer in the Ukrainian context. The reason was that Ruthenians-Ukrainians quickly became Polonized, despite constituting around 18% of the population, occupying a decent social and financial position, and being members of national organizations. Assimilation in the cities reinforced the stereotype that Ukrainians were a nation of peasants and priests.

*

The main source for research within this project is the press. All newspapers were in one way or another engaged and subjective. However, by comparing reports from different newspapers and aligning them with the general context, it is possible to clearly trace the priorities of each political group. What political leaders wanted to convey to their supporters, what they didn't talk about, and what message they wanted to send "externally" – after all, through the newspaper, one could speak on behalf of the whole city to an audience far beyond Lviv. Ultimately, the same things that were printed in the newspapers often mirrored what was communicated through street demonstrations. Therefore, if an event was covered by the government-owned Gazeta Lwowska, the democratic Kurjer Lwowski, the nationalist Słowo Polskie, the populistic Dilo, the Russophile Halychanyn, and the conservative Ruslan, one could form a more or less objective picture from these reports.

The images and photographs used in the project are mostly for illustrative purposes. Considering the wider distribution of Polish illustrated press, Polish national events are often more extensively covered than any Ukrainian events, for which finding illustrations is more complicated and not always successful. A separate emphasis in the project is placed on related individuals and locations in the city. We primarily used open sources – digital archives and libraries, mainly from Poland and Austria. We extend a special thank you to Dim Franka for generously providing photographs from the museum's archives.