What in the late 19th century looked like a demand by Ruthenian students at Lviv University to study in their native language evolved in a few years into a nationwide struggle to open a Ukrainian university. The range of political practices grew just as rapidly: from rallies and petitions to organized boycotts, occupation of premises, street battles, and negotiations with ministers. The situation was further complicated by the fact that the university in question was located in Lviv, a city symbolically important to both Ukrainians and Poles.

Background

In the late 19th century, Lviv University had four faculties (theology, philosophy, law, and medicine), with more than 3,000 students, of whom about 600 were Ukrainians. The language of instruction, examinations, and administration, despite the university's "utraquistic" (bilingual) status, was Polish. Only Ukrainian history, literature, and certain legal and theological disciplines were taught in Ukrainian.

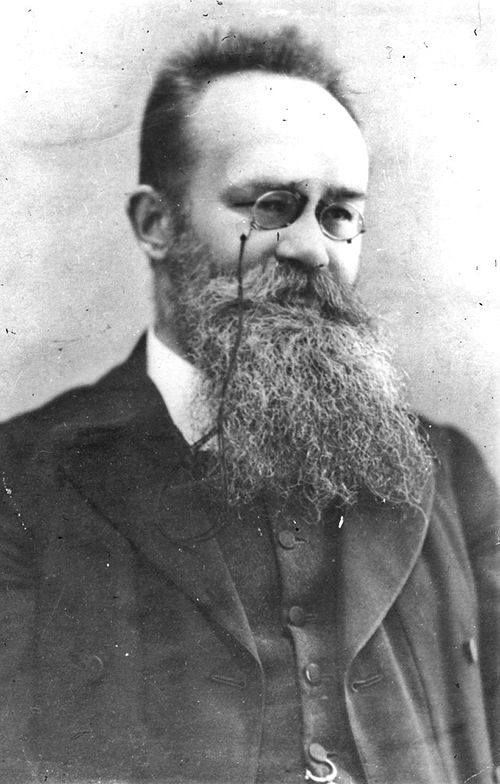

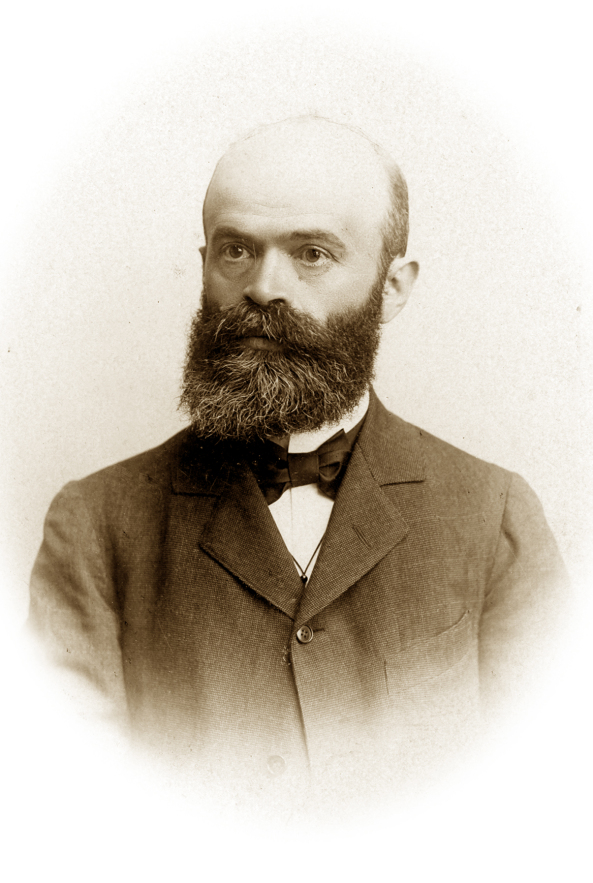

Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, a contemporary and eyewitness to many events related to the issue of a Ukrainian university in Lviv and one of the leading figures of the Ukrainian national movement, wrote about the university issue as a matter of "national justice." In his opinion, since the 1890s, the Polish status of Lviv University (the language of teaching and administration, the staff, and assistance from Polish politicians based in Vienna), reinforced by university autonomy and supported by local authorities, had ceased to meet the Ukrainian needs and prospects, which had grown significantly by the end of the 19th century. The Taras Shevchenko Scientific Society trained personnel who could take up positions at university departments, and negotiations were held with Ukrainian professors from the Russian Empire. Lviv was considered the center of the cultural and national life of Ukrainians in Galicia.

This was due, in particular, to the rather modest successes achieved by Ukrainians within the framework of the Ukrainian-Polish mutual understanding policy, the so-called "New Era", attempted in the late 19th century. Thus, in 1894, the Department of World History, with a special emphasis on the history of Eastern Europe, was opened with Ukrainian as the language of instruction, headed by Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, a historian and citizen of the Russian Empire. In 1900, the Department of the Ukrainian Language and Literature was established under the leadership of Kyrylo Studynskyi.

Initial demands and the beginning of organized confrontation

Students were the first to express dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs. However, it should be noted that when we talk about the student movement of that time, we are dealing with a political and national phenomenon rather than a "student" movement in the modern sense.

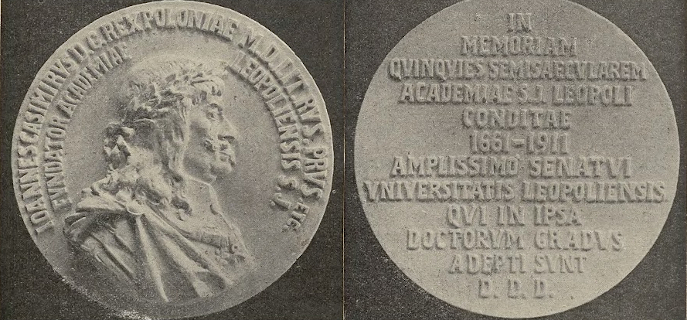

The Akademichna Hromada (Academic Community) student society, founded in 1896, initially organized boycotts of the Polish university departments by Ukrainian students. On 19 May 1898, at a solemn meeting of students "on the occasion of the Ukrainian national revival 100th anniversary," the society members decided to fight for the Ukrainian language at the university. In 1899, the first assembly of Ukrainian students in Austria-Hungary was held.

The Academic Community (Hromada) in 1896. Source: Encyclopaedia of the National Technical School of Ukraine

As the students' demands were not met, and the problem was not resolved in anyone's favour, it was only a matter of time before the conflict escalated. In March 1900, the first clash between Polish and Ukrainian students took place at Lviv University over the issue of the Ukrainian language. Twenty Polish and three Ukrainian students were injured. The student movement was increasingly going beyond language demands. On 14 July 1900, a student assembly was held, the participants supporting the thesis of the Ukrainian people's independence. The authorities in Vienna did not officially respond to the memorials of either this assembly or the previous one (held in 1899). The students continued to organize rallies, for example, on 3 and 8 October of the same year meetings were held with approximately 300-400 participants.

The case reached the imperial level as Ukrainian parliamentarians began to promote it in the State Council and the government. On 20 December 1898, Danylo Taniachkevych spoke in parliament on the matter. On 13 July 1899, a meeting of Ukrainian students at Austrian universities was held at which Lonhyn Tsehelskyi delivered a memorial speaking about a separate Ukrainian university and not just about Ukrainian departments within the existing one. On 19 November 1901, Yulian Romanchuk addressed the Austrian parliament with a proposal that the government submit a draft law on the establishment of a Ukrainian university in Lviv, and prior to its establishment, on the establishment of parallel departments with Ukrainian as the language of instruction.

At the same time, the extreme right-wing ideas of the Polish National Democrats (pol. Endecja) were becoming increasingly popular among Polish professors and students, so concessions to the Ukrainians were out of the question. In their view, the Ukrainization of the existing university, and even more so the creation of a separate Ukrainian university, threatened the "Polish proprietorship" in Galicia. For the Poles, university affairs also shifted from a purely educational to a national and political dimension.

Secession

As the situation was not resolved either at the level of the university itself or at the level of the government, the confrontation was growing increasingly acute. On 19 November 1901, when Yulian Romanchuk was speaking in parliament, Ukrainian students held a general assembly at the university, despite the university administration's ban. It ended with the singing of the hymns "Shche ne vmerla" and "Ne pora"; later, however, five students were expulsed.

On 1 December of the same year, another assembly was held, where it was decided to leave Lviv University and move to other universities of the empire. On 3 December 1901, 440 Ukrainian students left Lviv University. Since Chernivtsi University refused to accept them, they continued their studies in Vienna, Prague, and Krakow. The students' withdrawal from the university ("secession") received considerable publicity, and a special financial fund was set up to support the students so that they could continue their studies outside of Lviv. The action was supported, both morally and financially, by Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, who backed the theological students at his own expense. Despite the fact that no concrete results (other than wide publicity) were achieved, a youth congress held in Lviv on 25-27 July 1902 decided to end the secession and return to Lviv University. Moreover, the government in Vienna did not start a dialogue until the secession was terminated.

At the same time, the secession experience largely determined the Ukrainian movement trends in the following years.

Firstly, the Ukrainian national movement, due to the secession itself and the subsequent fundraising, demonstrated good mobilization capabilities. The issue of the Ukrainian university was discussed at meetings even in the most remote villages.

Secondly, there was further politicization of student life. The historian Ivan Krypiakevych wrote in his diary that it was under the influence of the student unrest and secession of 1901 that many students of the gymnasium where he studied at the time felt Ukrainian. He himself formed his political views under the impression of the secession and under the influence of the Akademichna Hromada activities. On the other hand, he also criticized the student periodical Iskra for its unjustified anti-clericalism, criticism, and lack of specifics. Student life, Ivan Krypiakevych argued, was completely absorbed by politics, leaving no room for studies and research.

Thirdly, Ukrainians began to actively develop institutions alternative to the official ones. On 4 December 1901, students Stanislav Dnistrianskyi, Oleksandr Kolessa, and Yevhen Ozarkevych submitted a petition to the Austrian parliament to establish a private Ukrainian university in Lviv, the funds for which could be raised through a voluntary tax. On 20 March 1902, Mykhailo Pavlyk delivered a report entitled "The Free Ukrainian University" at a meeting of the philological section of the National Technical School. However, the idea of a private university was not supported by everyone, because it would not have had an official status. There were also examples of real work: in the summer of 1904 Mykhailo Hrushevskyi organized Ukrainian studies courses in Lviv, and in the spring of 1905, on his initiative, the Archaeographic Commission of the Shevchenko Scientific Society resumed its work.

Further radicalization and violent confrontation

In spite of the fact that some Polish and Jewish students stood in solidarity with Ukrainians and that Ukrainians were initially supported by the Polish Social Democrats, the main Polish student organization at Lviv University, the Czytelnia Akademicka (Academic Reading Room), influenced by the secret union of Polish youth, Zet), worked to secure the status of the university as a Polish institution. A meeting of Polish students on 28 November 1901 condemned the Ukrainian actions, and the university was proclaimed "an asset of Polish culture." The Polish press saw the Ukrainian student actions as "politics" rather than a demand for legal rights. While not opposing the Ukrainian university in the long run, they spoke of a threat to the status of the already existing, de facto Polish university.

- Станіслав Ґломбінський / Stanisław Gląbiński

- Титульна сторінка брошури Ґломбінського / The title page of Gląbiński's brochure

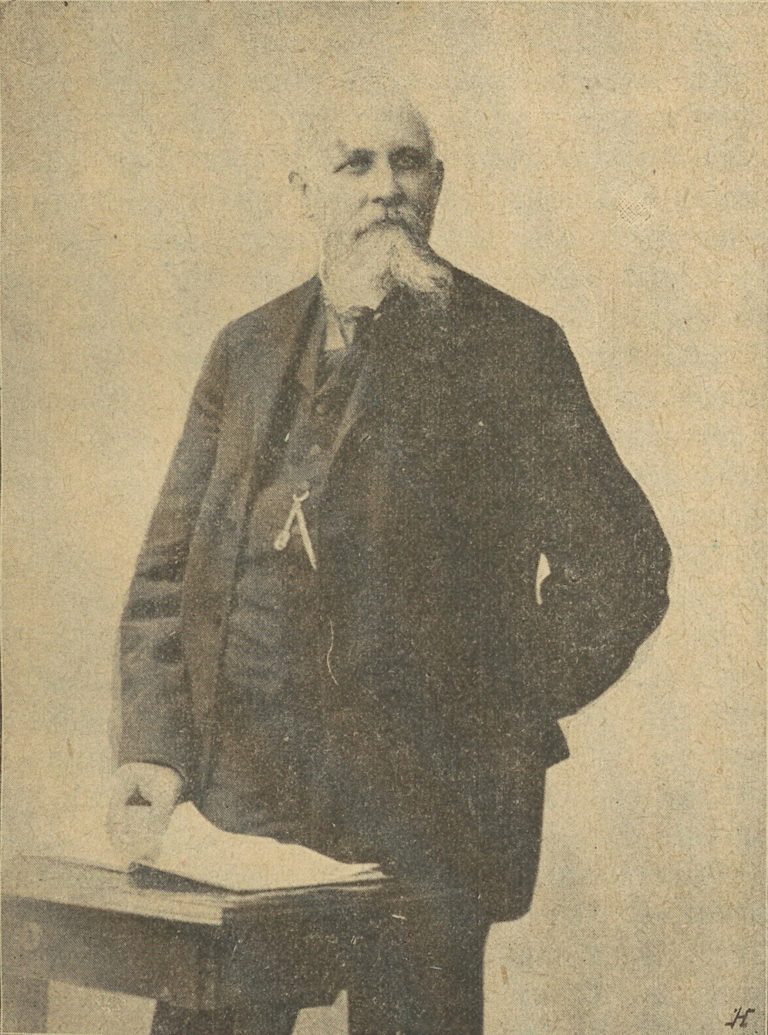

In March 1902, the Polish press reacted sharply to the Ministry of Education's minor concessions regarding the use of the Ukrainian language. At the same time, Stanisław Głąbiński published a brochure with the telling title "An Encroachment on the Polish University in Lviv." Bringing the issue to the national level, presenting the Ukrainian demands as an attempt to "destroy the Polish university" and "attack the Polish character of the province," the Poles held the first national assembly in Lviv on 30 May 1903. It is noteworthy that it was in Lviv that Polish society refused to accept the proposal to establish a Ukrainian university, as the city was so symbolically important. Ukrainians also did not consider the possibility of opening their own institution somewhere else in the province.

After the attack by Ukrainian students on Rector Jan Fialko on 16 October 1903, Polish Social Democrats (the only ones in the Polish camp who were sympathetic to Ukrainian demands) condemned such methods of struggle, calling them "nationalist cretinism." The Polish Czytelnia Akademicka responded to the attack by "purging the university of the Haidamaks", i.e. by Polish students' violent actions against Ukrainian students.

After the revolutionary events in Russia in 1905, the situation escalated again, partly under the influence of the news and partly due to the relocation of many revolutionary elements from the Russian Empire to Lviv. In late October 1905, the University formed an "Organization for University Affairs" consisting of 74 students, with Ivan Krypiakevych as secretary. Meetings were held once a month, and there was a system of membership fees.

On 25 February 1906, the rector's ban on the use of the Ukrainian language for communication with the administration was discussed in the Akademichna Hromada premises. The fact is that during an audience, students submitted a petition to the rector in Ukrainian while he demanded it in Polish, so another conflict arose. It is noteworthy that, along with the prospect of reprisals against students for the intended demonstrations and the Sejm reform cause, the meeting also discussed more practical issues — for example, what to throw at opponents.

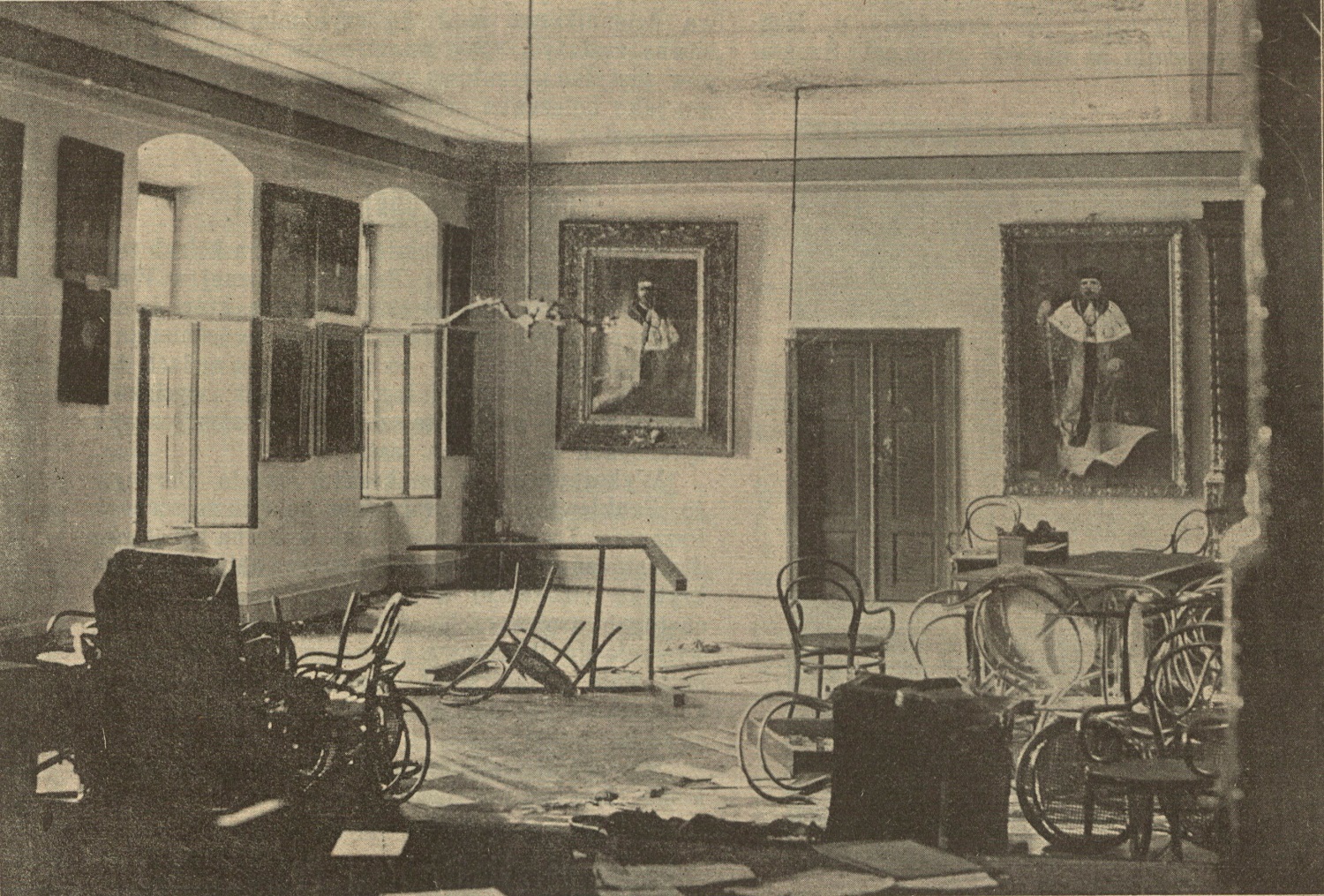

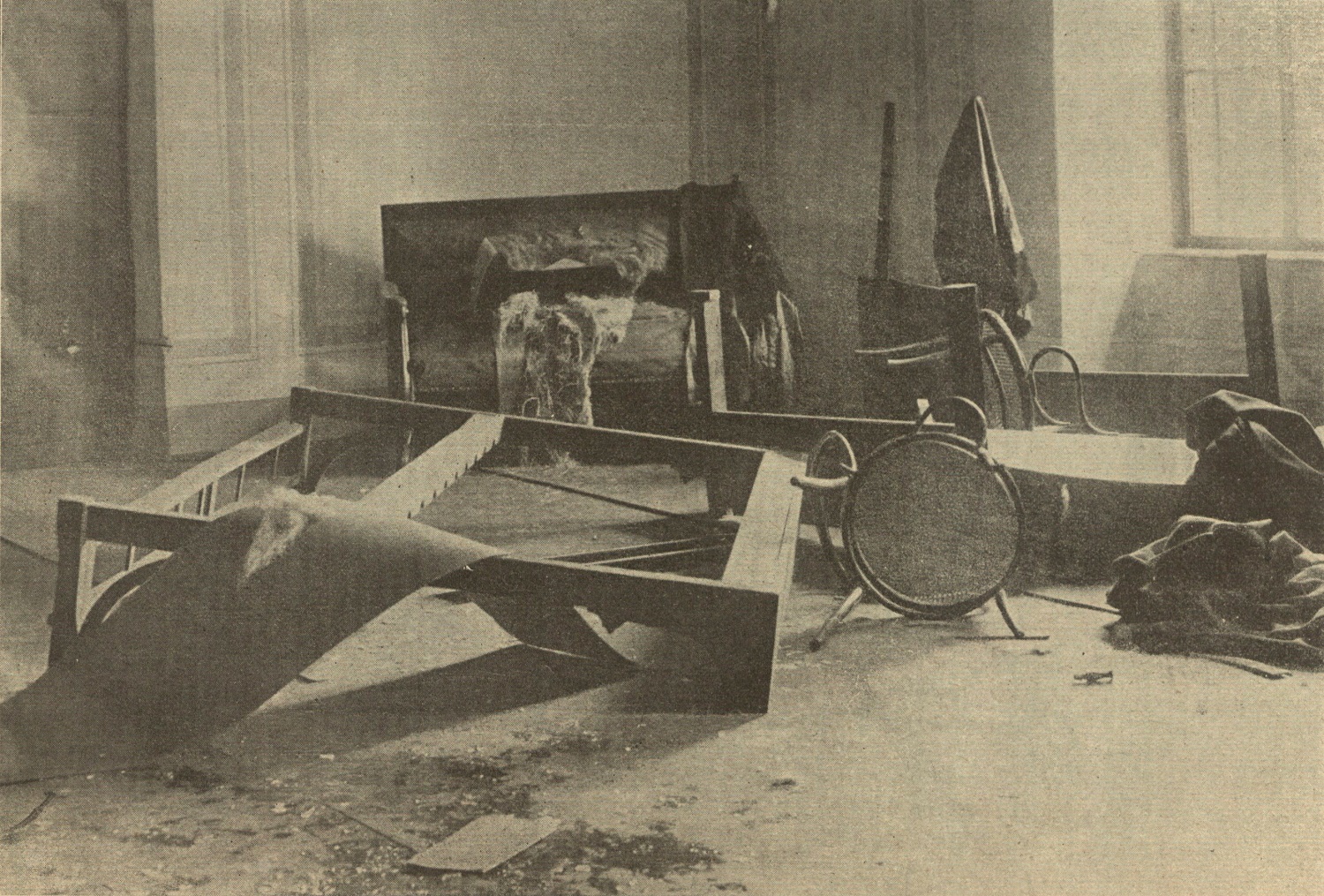

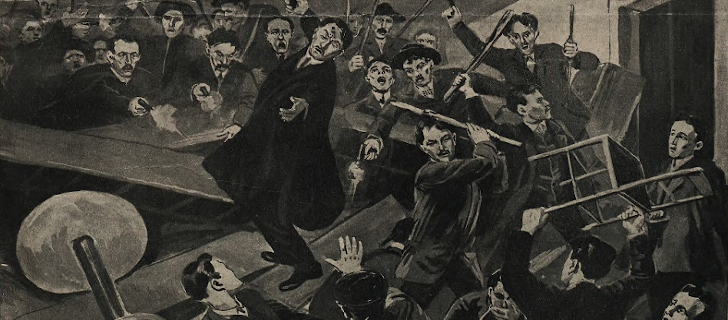

In 1907, the issue of the Ukrainian language use, as well as the right to the students' assemblies in the university building, was on the agenda again. On 22 January, the Ukrainian students decided to protest by staging one of the largest riots. On 23 January, they beat up the university secretary, Alojzy Winiarz, seized the ground floor of the university building on ul. St. Nicholas (now vul. Hrushevskoho), constructed 5 barricades, destroyed 20 portraits of rectors, damaged the large meeting room, smashed windows, busts and portraits of emperors and Polish figures. A blue and yellow flag was hung from a ground floor window.

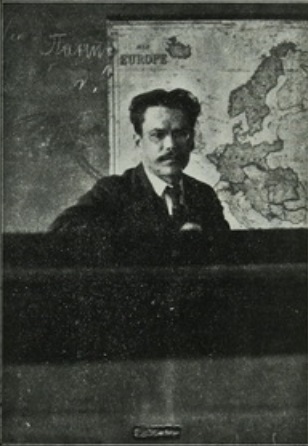

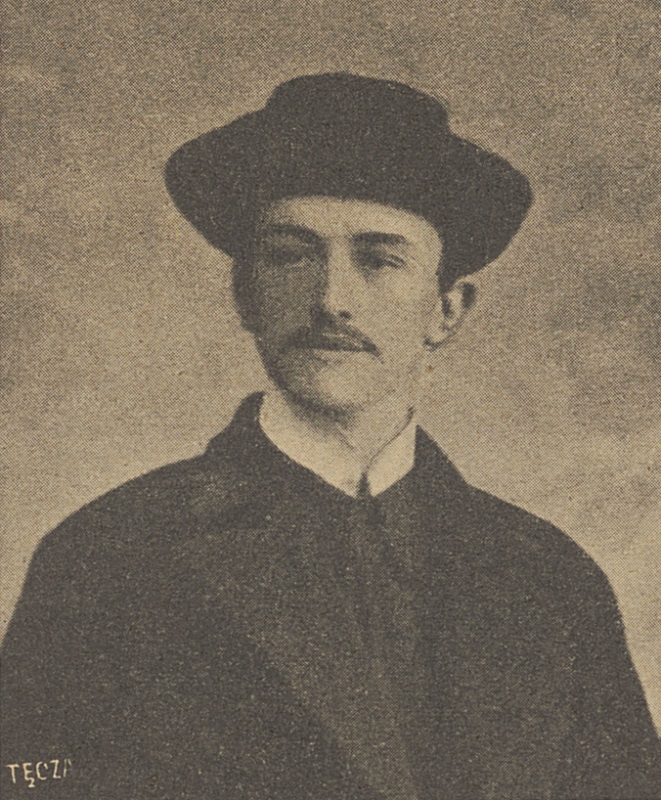

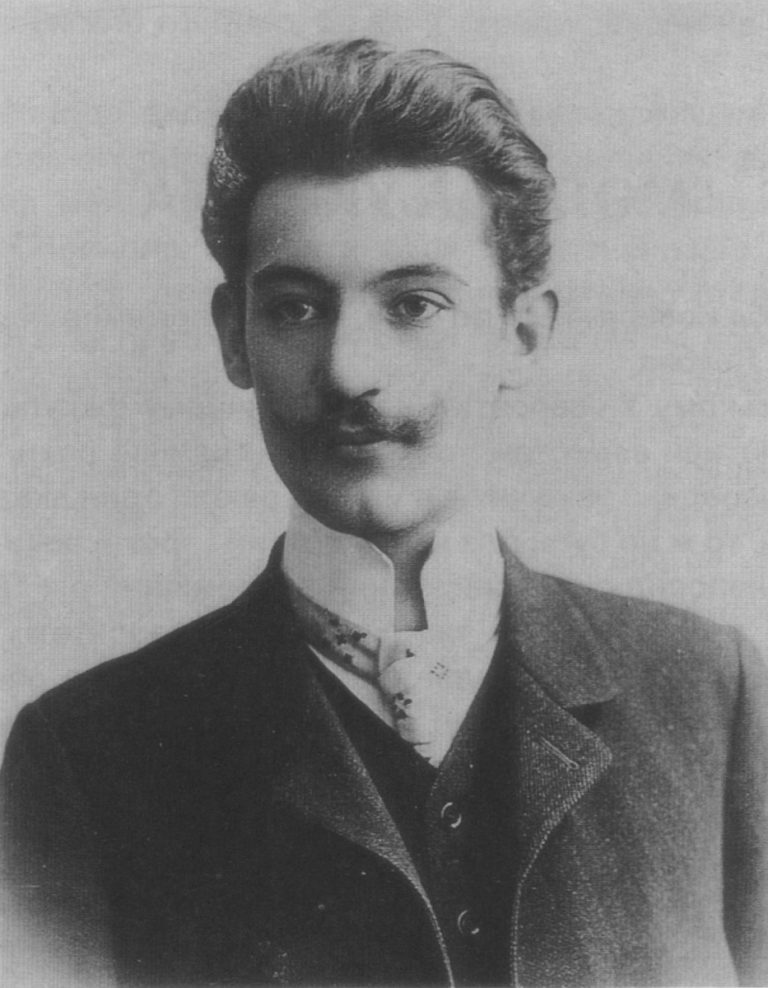

One of the most active participants in this riot was Pavlo Krat, a student born in Dnieper, Ukraine, and a socialist who moved to Lviv in 1905. He studied at the university together with Myroslav Sichynskyi, Adam Kotsko, and Ivan Krypiakevych. It was Pavlo Krat who, wearing a rector's robe, cut up the portraits of the rectors.

The police detained 99 students (hence "the case of the hundred"), including Myroslav Sichynskyi, Volodymyr Levytskyi, Ivan Krypiakevych, and Petro Karmanskyi. After writing reports, they were released; however, on the governor's instructions, they were detained again on 1 February. At the same time, the charges were changed from terrorism to violation of public order. The most famous Ukrainian lawyers (Kost Levytskyi, Mykola Shukhevych, Volodymyr Starosolskyi) volunteered to defend the students for free, but the case did not go to court. The Ukrainian students who were free held an assembly, while the prisoners went on a hunger strike that started on 21 February and lasted four days. They demanded to be released and not tried as prisoners. The provincial court agreed to release only those whom the continuing hunger strike put in danger due to their health condition, but the students themselves did not agree to this. Eventually, under pressure from the Western press, the detainees were released on 27 February, but the situation became even more radicalized as they were greeted as heroes on their release.

Pavlo Krat was initially planned to be transferred to Russia, but he managed to leave the country and moved to Canada. There, he was engaged in political activities, including publishing the newspaper Chervony Prapor (Red Flag), where he wrote, among other things, about the struggle for the Ukrainian university in Lviv.

As a result of the growing conflict, the ideas of the Polish national democrats gained more and more support not only among students and teachers. The university administration, the City Council, the Diet (Sejm), and student societies also took nationalist Polish positions in regard to the case of Lviv University.

On 3 March 1907, an assembly was held in defence of the university's Polish character. The governor, Count Andrzej Potocki, openly opposed the Ukrainian university, interpreting it as a possible germ of real political ambitions of Ukrainians.

Eventually, the university administration's insistence on the use of Polish instead of Latin (during the so-called "immatriculation", or "enrolment", the ceremonial admission of students) and the Ukrainian students' outrage over this caused another bloody clash in the same year, on 14 December 1907.

After the assassination of the governor Potocki by Myroslav Sichynskyi in 1908, new clashes between students took place, in particular near the Akademichna Hromada building, after the Poles held a rally near the Mickiewicz monument.

A certain lull was brought by external factors. Firstly, in 1908, members of parliament from the "small nations" of Austria-Hungary demanded the establishment of national universities in the parliament, which meant that Ukrainians could count on greater support in the State Council. Secondly, the same year saw the Austrian-Russian escalation and the Bosnian crisis. Accordingly, to maintain interethnic peace, the central government decided to rely on the most loyal and trustworthy politicians of Galicia: the Krakow conservatives (so-called stańczycy) and the populists. A temporary Austrophilic, supposedly "governor's" political bloc was formed.

The law on universal suffrage of 1907 significantly strengthened the position of Ukrainian parliamentarians, who could now raise the issue of establishing a Ukrainian university more effectively. After 1907, when Ukrainian representation increased, Stanislav Dnistrianskyi and Oleksandr Kolessa, professors at Lviv University, became members of parliament for the first time. The demand for the establishment of a university was included in the Parliament's Ruthenian Club programme. On 28 June 1910, Greek Catholic Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky spoke in the House of Lords in defence of the right of Ukrainians to study in their native language. Eventually, Ukrainian parliamentarians agreed that in case of the foundation of a Ukrainian university in Lviv, the existing one would remain Polish. In this case, the Shevchenko Scientific Society was to be reorganized into an academy.

The culmination of the violent confrontation between Ukrainian and Polish students was the 1910 riots, which ended with the murder of one of the participants, Ukrainian Adam Kotsko.

* * *

After that, the struggle for the Ukrainian university moved into a more legal political channel. Several compromise options were proposed, but no agreement was reached. The Ukrainians insisted on separating their "own" departments around which a full-fledged university was to be formed within five years. The Poles protested against the withdrawal of any research and scientific facilities from the existing university in favour of the Ukrainian one. The government sought to postpone the creation of the Ukrainian university, first for ten years, then for six years. Finally, negotiations to open it by 1916 reached a deadlock in 1913. Only on the eve of the First World War, in early 1914, under pressure from the government, an agreement on a Ukrainian-Polish understanding was reached, which included the opening of a Ukrainian university in Lviv and the Sejm reform. The issue of the university was revisited during the war itself: a secret protocol of the Brest Peace Treaty provided for the division of Galicia into Polish and Ukrainian parts, meaning that in theory the case should have been resolved in favour of the Ukrainians. In reality, the university in Habsburg Lviv remained Polish and, formally, bilingual. In 1921-1925, after the closure of the Ukrainian departments at Lviv University, the Secret Ukrainian University functioned illegally in Lviv.