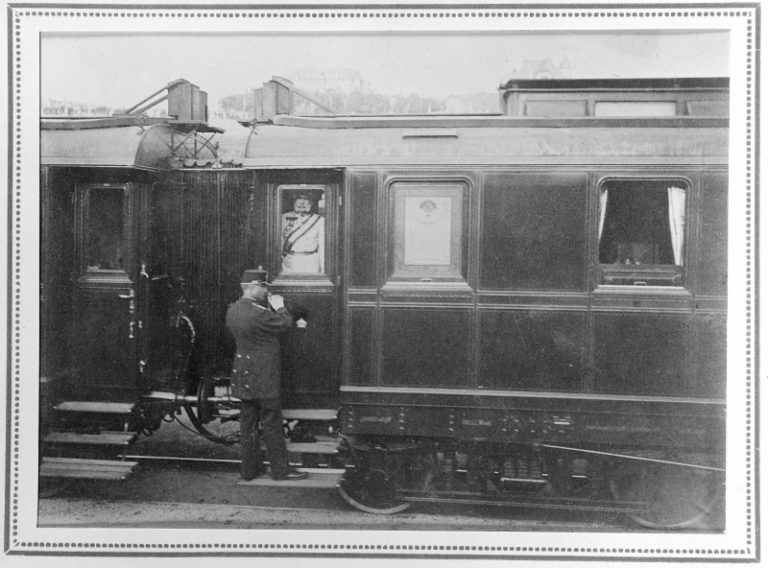

Franz Joseph visited Lviv five times. However, even in his absence, the Lvivians had the opportunity to celebrate in his honour, occasionally showing their loyalty and gratitude to the beloved monarch. While the main celebrations took place, as a rule, in Vienna, in Lviv they burnished their own rituals, which became increasingly massive over the years, the programs becoming more intense. Of course, these celebrations are not comparable to the emperor's visits, but they also contained all the "mandatory attributes" of the imperial celebration, which were attended by officials, military, clergy and "grateful people."

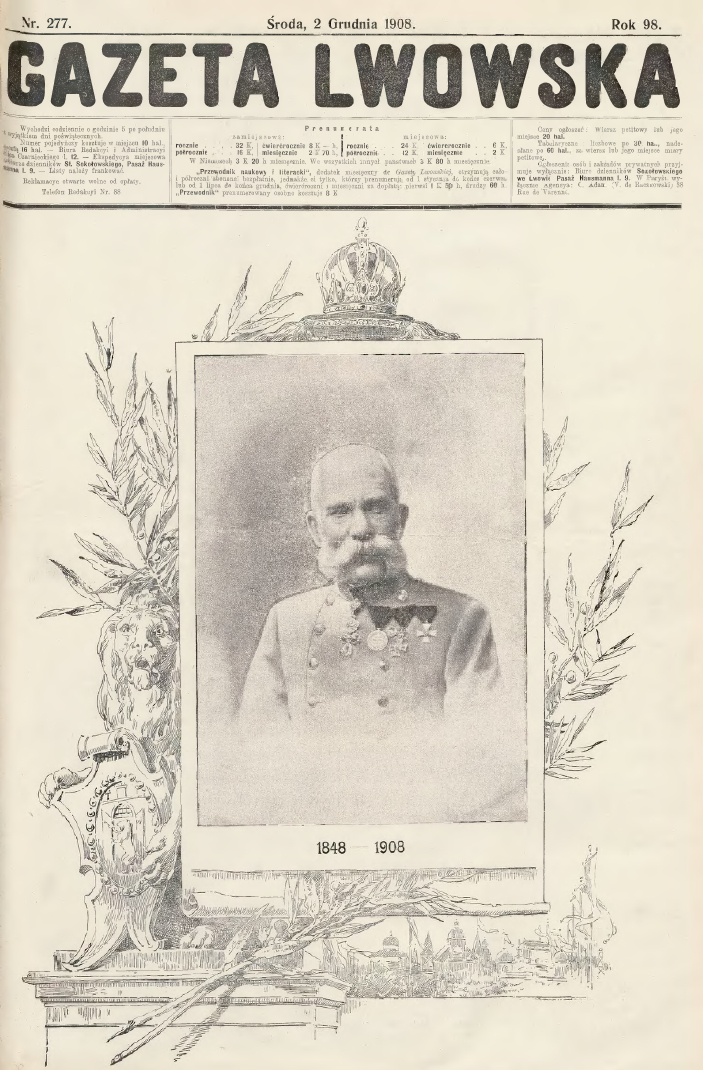

There were key dates celebrated officially: the beginning of Franz Joseph's reign on December 2 (1848), his birthday on August 18 (1830) and his name day on October 5. Naturally, in this calendar there were some "good round" anniversaries drawing more attention. So, new events could be added to the obligatory list, while the usual ones were held more solemnly. These included, for example, 25 years of the emperor's reign in 1873 or 60 years of his reign in 1908. Also, his wedding anniversary with Duchess Elisabeth of Bavaria was celebrated on April 24 (1854), and the "silver wedding" was celebrated in 1879.

Such celebrations became especially popular after the establishment of the constitutional monarchy (1867), acquiring a bright patriotic character, with the involvement of the masses. In Galicia, for example, there were genuine "Polish-Ukrainian illumination competitions", when each community sold "their own" "illumination cards" (as part of fundraising for charity) and printed their own polygraphic products in which the language of inscriptions or "national fonts" was important.

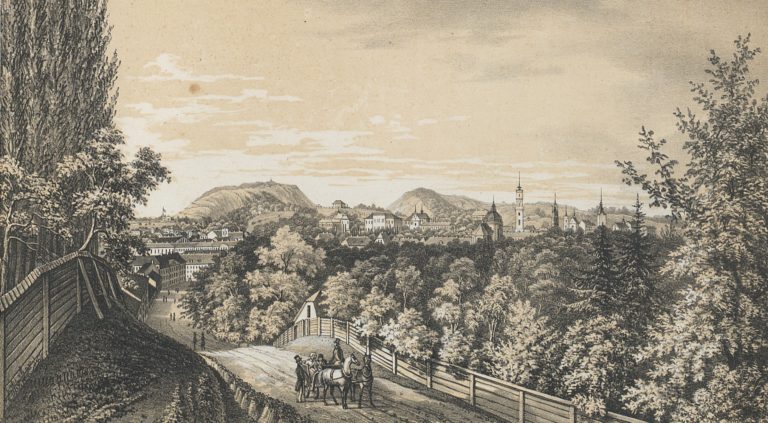

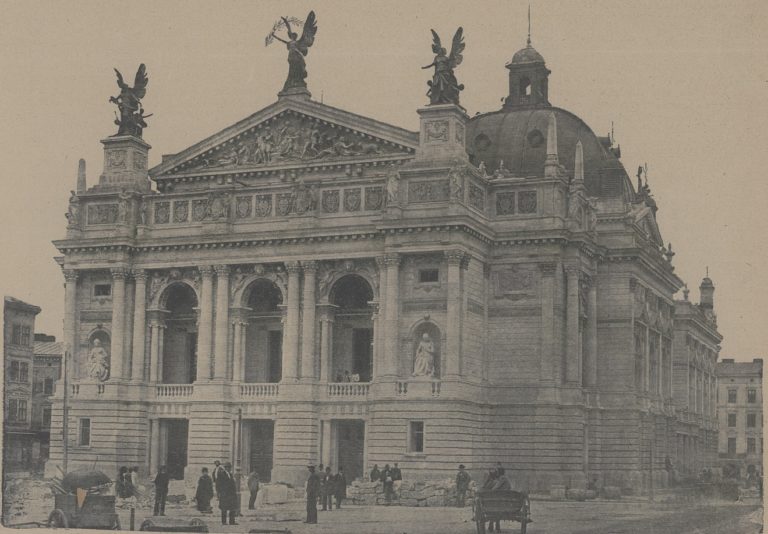

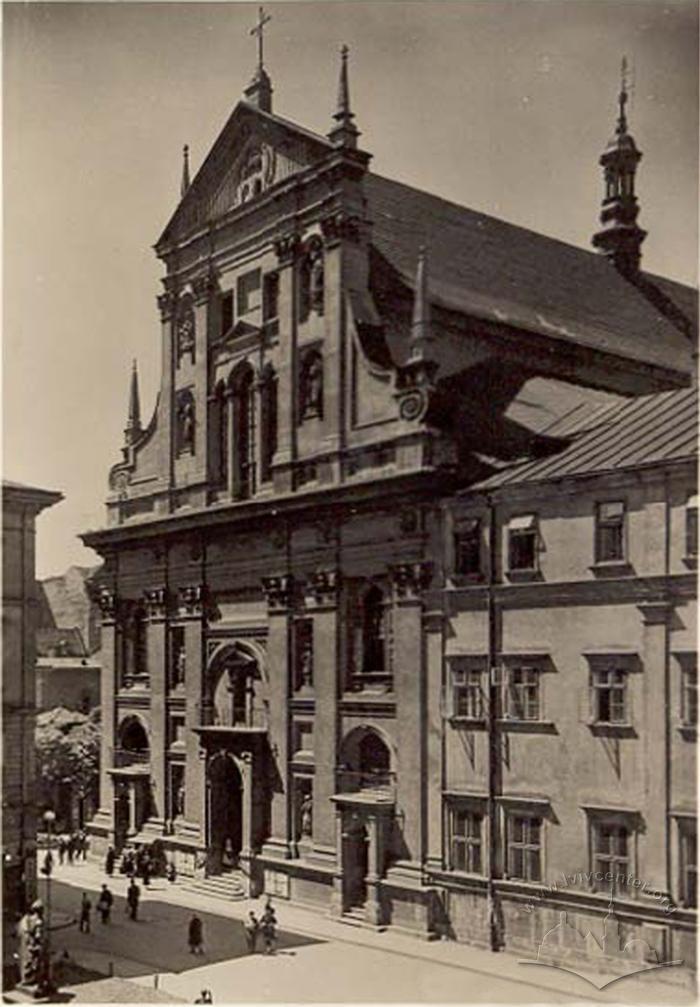

On occasions like these, Lviv hosted a classic set of celebrations for the province: a meeting of the City Council (with greetings sent to Vienna), military parades, evening illumination, special events in schools, societies and so on. Lvivians decorated their houses with flags, and a military band marched through the streets playing patriotic melodies. Festive services were held in churches, cathedrals and synagogues of the city, which were attended by government officials. Officers were awarded in the garrison church (Jesuit church), and the governor held receptions. In the evening, theaters offered special programs. The press described all this in detail, thus illustrating the emperor’s popularity among the peoples of the empire.

One of the main images used to consolidate society was the image of the benefactor emperor. After natural disasters or before certain holidays, Franz Joseph used to donate large sums of money; in addition, he was a patron of certain charitable foundations, committees, and organizations. The greater the contradictions in the empire (for example, between the supporters of Pan-Germanism and the enthusiasts of a federation of nations), the more important was the symbolic role of the emperor as a unifying factor. Therefore, during the celebration of the 40th anniversary of his reign in 1888, the emphasis was shifted towards charity and helping the poor. In 1898, the celebrations were cancelled due to the murder of Franz Joseph's wife, Elizabeth of Bavaria (Princess Sisi), on September 10.

Tracing the evolution of celebrations in time, one can see not only the mentioned political aspects but also how much richer and more massive the programs of celebrations were becoming, how the celebrations of "the officials and the military" were becoming universal and how they were acquiring national colouring.

1870th

In the 1870s, Lviv celebrated two "good round dates": the 25th anniversary of the reign of Franz Joseph on December 2, 1873, and the "silver wedding" of the royal couple on April 24, 1879. The main ideological motive of these celebrations was "peace and harmony in which the peoples of the empire live, especially against the background of crises and conflicts in Western Europe." On the occasion of the anniversary of the emperor's reign, aristocrats, imitating the beloved monarch, donated money in favour of "the poor of the city of Lviv." Before the "silver wedding" a special committee of the City Council decided to transfer funds for a Jewish orphanage. Representatives of other classes did not lag behind. Professors, associate professors and assistants of the Polytechnic School raised money to award the best students, who would display their works at that year's exhibition. Mrs. Berta Lang, a hotel's owner, donated "200 loaves of bread to those in need, regardless of their religion."

In the 1870s, some celebrations were still quite exclusive, inaccessible to the general public. For example, on December 1, 1873, a concert for the City Council and some invited guests took place in the City Hall. Similarly, the 1879 celebration of the "silver wedding" began the day before with a performance in the theater. Representatives of "the authorities, elected bodies, and corporations" were present at the festive services at the Latin Cathedral. Then the governor received representatives of the clergy, senior officers, officials and members of the City Council at a dinner party. Some programs took place in societies and in the cadet school.

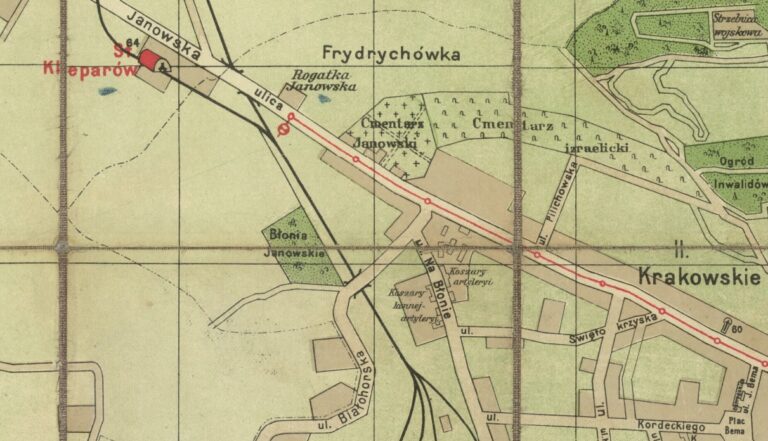

The military were involved in the anniversaries in two ways. Traditionally, on such days, the entire Lviv garrison went to the parade ground or "to the meadows" behind the city turnpikes for a field mass and a ceremonial line-up. The second option was for a military band to march playing through the streets on the eve of the anniversary in the evening (with torches) and on the day of the anniversary in the morning. On December 2, 1879, the only time it happened that the Lviv garrison soldiers — three infantry regiments, an Uhlan squadron, artillerymen, paramedics and a group of disabled military veterans — lined up not outside the city but near the Latin Cathedral and on the surrounding streets. At 12 a.m. they marched in front of General Fiszer. He was the only general to remain in Lviv, as the rest went to Vienna to greet Franz Joseph in person.

During the festivities citizens could enjoy the evening illumination of the main buildings in the city center, as well as decorations, mostly flags, which were associated with the imperial couple, in the colours of the Habsburgs (black and yellow) and the Wittelsbachs (blue and white). In the press, they were called "state" and "Bavarian." In some places there were images of the imperial couple, decorated with banners and garlands.

1880th

In the 1880s, the ritual was supplemented with some new elements and also became more massive and focused on the general public. In the evening and in the morning, military bands began to march not just through the city center, but "from the city center through all the main streets." In addition to the elite, "broad sections of the Lviv public" were present at the morning services. Representatives of corporations also began to attend the governor's reception. Even the number of those invited to dinner with the governor increased from about 40 to 65 people.

On August 18, 1880, on Franz Joseph's 50th birthday, the city was greeted by cannon volleys from the citadel at 5 a.m. The parade on Jabłonowskich Square was also more numerous: 9,000 military men took part in it. After the solemn service, there were 24 cannon volleys again. When during the dinner at the officers' casino a toast was proclaimed for the emperor, an artilleryman on the City Hall tower signaled the citadel and 24 volleys were heard again.

"According to the wishes" of Franz Joseph, as the government press wrote, the celebrations on December 2, 1888 (on the occasion of 40 years of his reign) were quiet and modest. They were limited mainly to worship and charitable donations. It was an opportunity, as newspapers said, to "reflect on his charity and care." In particular, it was about the emperor's good attitude to the peoples of the empire, his support of education and help to the poor. The main part of the materials in the press was occupied by the list of donations to various provincial funds.

In 1890, on the emperor's 60th birthday, a tradition was initiated of raising state flags (as a symbol of power, not as an element of decor) on the City Hall tower, the governor's office and other government buildings.

1900th

In the early 20th century, there was a growing demonstration of ethnic patriotism and more active participation on the part of public organizations. The main idea promoted in the press was the person of Franz Joseph as a guarantee of national rights and equality of citizens. In times of political struggle and instability (now within the empire), the emperor was considered the only reliable support of the social order, the defender of the weak and the oppressed. In addition, the then newspapers wrote about the "equality of the province among other provinces" (meaning in fact the Polish national autonomy).

On August 18, 1900, on the 70th birthday of the emperor, the Riflemen's Society invited its members to gather half an hour before the service in the City Hall. The dress code for the day was festive or "folk."

The houses, now even far from the center, were decorated with flags the day before, and now not only with state ones but also with those of the region and the city as well as "national" ones. Balconies were decorated with garlands, greenery and busts of Franz Joseph, genuine installations were placed in banks and hotels. In the evening, four bands of four regiments stationed in Lviv played first on St. Spirit Square and later went to different parts of the city. Crowds of curious people accompanied them on the streets.

In the morning, at 5 a.m., there were traditional artillery volleys and "wake-up call" from a military band. At 7 a.m. the garrison went to the Yanivski meadows, where the field mass began at 8.30 a.m. During the mass, the military fired three carbine volleys three times, and cannons (8 volleys each time) answered them from the citadel. Later, there was a parade, which was watched by ordinary spectators and army veterans.

At 9 a.m. solemn, now thanksgiving services in churches began. The authorities (as well as German and Russian consuls) were present in the Latin Cathedral, along with representatives of the University and Polytechnic, societies, corporations. This time, however, some of those in power were present in St. George's Cathedral and the Armenian Cathedral. All services in all churches of the city ended with the anthem singing.

The governor received deputations who paid their respects and loyalty to the emperor: first the clergy, then the Marshal of the Sejm, the German consul, university professors, school directors, representatives of the Credit Society, the Chamber of Commerce, the Fire Society, members of the Ukrainian societies: Prosvita, Shevchenko Society, Pedagogical Society, Narodna Torhivlya, Dnister, Ruska Besida, Credit Union, Craft Society Zorya, Society of Veterans, etc. At this time, a choir sang the anthem in front of the governor's office.

At 4 p.m., a dinner for 68 persons began in the governor's office. During the dinner, a military band played in front of the governor's office. When the governor toasted the emperor, the band played the anthem and 24 cannon volleys were fired from the citadel. In the evening, residents traditionally watched the illumination, while a "national program" was demonstrated at the Skarbek Theater. The illumination (at least its description in the press) changed: now the windows of private homes were also part of it, and this did not only apply to buildings in the center. Besides, the illumination itself lasted until 11 p.m. Due to the fact that the decoration of houses became widespread, the city authorities asked residents to pay attention to the telegraph wires and not to damage them.

A novelty of the 60th anniversary of the emperor's reign on December 2, 1908, was the fact that residents began to glue stickers with the image of the emperor on the windows, the so-called illumination cards, which they specially bought with this in view. This was to replace or supplement the candles and lamps used so far. Multicoloured sparklers, electric lighting and light installations around sculptures on buildings began to be widely used. A colourful bonfire was lit on the Union Mound. The houses were decorated mostly with "state and national" flags, and residents walked in the city until late.

Mass awarding of orders to many dignitaries was also a novelty.

More events were held in societies and organizations. For example, at a solemn meeting of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry they spoke about the changes that had taken place in Galicia over the past 60 years, about freedom, free development of peoples and social groups. A festive dinner was held in the Shooting Gallery for more than a hundred guests, led by Governor Michał Bobrzyński. Similar events were held by Ukrainian and Jewish societies, which also spoke about the equality granted by the emperor.

The rest of the program was standard: military bands, cannon volleys, solemn services, a reception at the governor's, an evening at the theater, flags on administrative buildings.

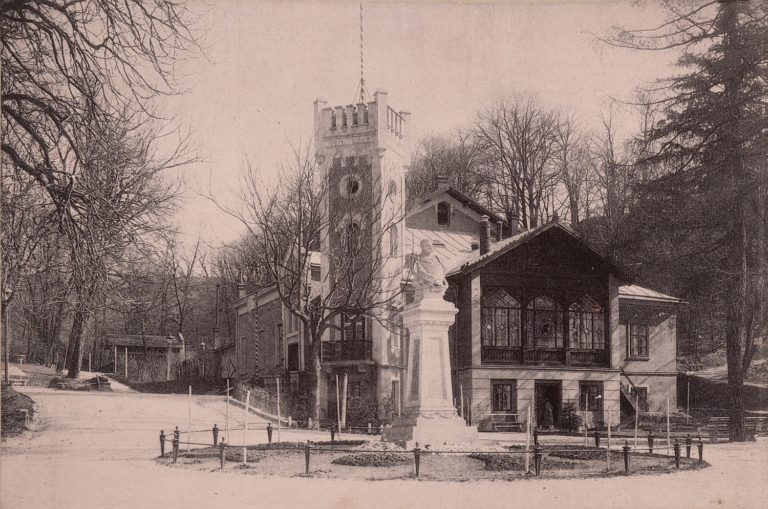

Also, in 1908, a monument to the emperor was erected in Lviv next to the cadet school.

The service in the Latin Cathedral was attended by leading figures of the governor's office, the Sejm, the City Council, the University and the Polytechnic, societies, corporations, fraternities. Similar services were held in other churches; however, the presence of students and teachers (centralized and organized) was a novelty. The military gathered in the Jesuit church. Then, there was a solemn meeting of the City Council. In the place of the president of the city, there was a bust of the emperor. The president of the city traditionally spoke about equality of the people and freedom, as well as about progress, because "60 years ago, this part of Poland was a land of poverty and despair."

After the service, all those who had not left for Vienna hurried to the governor's office to prove their loyalty to the monarch. The reception lasted until 1 p.m., as there were many visitors belonging to all denominations and classes. At 4 p.m., the governor's traditional dinner began.

* * *

During the decades of Franz Joseph's reign, over the years the classic list of bureaucratic and military events was supplemented with elements making the celebration of the emperor's anniversaries truly universal. While initially these events were clearly focused on officials and the army, over time, various societies, schools, and corporations became participants in the celebrations, and these subjects of civil society became more and more numerous. At the same time, old rituals such as parades of military bands, illuminations, and worship were becoming more and more public-oriented.