The second half of the 19th century in Europe was the time of nationalism, mass rituals and commemoration, which were to strengthen the position of the then elites. In celebrating birthdays of the emperors of Russia or Austria-Hungary, republican holidays in France or anniversaries of Germany's victories, official patriotism was complemented by the practice of honoring writers and other "national heroes." Through the involvement of large masses of the population (due to rail transport and the press) it was possible to turn subjects into nations.

Polish society did not remain aside from these processes. Celebrating the anniversaries of past victories proved to be a much safer activity than preparing for a new uprising. Besides, it was perceived as more patriotic than "organic work." Moreover, in the conditions of the division between Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary, the Polish elites emphasized the "construction of society" without challenging the existing empires.

In the context of mass politics, Masurian peasants were involved in the Polish national project, which was no longer meant exclusively for nobility. Since there was competition within the Polish elites themselves, the events they organized were really supposed to be popular among the common people. It was a more difficult problem of how to involve non-Poles in this modern national project however. But a surviving tradition made them return to the idea of a voluntary union of Poland, Lithuania and Ruthenia time and again.

Thanks to the celebrations, it was possible to symbolically "erase the borders" of the existing empires and to gather representatives of "the whole nation" in one place. The most favorable conditions for such activities were present in Austria-Hungary.

* * *

During the period of Galician autonomy in Austria-Hungary, Polish elites learned to use the imperial ritual to promote their "national agenda." Acting as power (in the symbolic field), they seemed to become power themselves. This was facilitated by legislation that had become quite liberal after the reforms of the second half of the 19th century. Local authorities were given the right to close shops during mass events, to decorate houses, to arrange illumination and to organize municipal guards. Moreover, they could spend real money to do all these things now. The Lviv City Council paid considerable attention to the work "in the symbolic field." It took full advantage of these opportunities, balancing between loyalty to Vienna and a desire to "revive Polishness."

Some of the examples of celebrating national anniversaries are clear markers of changes that were taking place in the local politics, especially those celebrations that were organized as mass events. In a way, they were similar to the erection of monuments, which was also a kind of marking public space, but one which happened more often and evolved over time.

What changed exactly? For example, it was the relations between Vienna and Lviv, Lviv and Krakow, between Poles and Ukrainians or Jews. The "authority" changed as well: the City Council played an increasingly important role, while the governorate was transformed from a center that dictates conditions and imposes bans, into an honorary participant in mass events.

The role of ordinary participants also changed: from personal participation under the supervision of the police commissioner (as during lectures given in the City Hall on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Constitution of the 3rd May in 1891) to anonymous presence at a march with a red banner (on the anniversary of the January Uprising in 1913), from moving in small groups to the gathering place (on the 300th anniversary of the Lublin Union in 1869) to an organized passage through the triumphal arch (on the 100th anniversary of the Constitution of the 3rd May in 1891).

Militarization and politicization of mass events were two other important transformations. Following the imperial rituals, the local Polish elites used to organize a "military reveille" by the municipal orchestra and a "guard of honor" with the help of scouts (this was especially evident in 1913). The ideological content of the events became crucial. For the democrats, anniversaries of uprisings or examples of the involvement of the "people" in the broadest sense of the word were the most important. The conservatives were more willing to honor the constitution or military victories of the distant past.

Changes in attitudes towards Ukrainians and Jews, as well as their involvement and its terms, are also interesting to note in these processes. And so are the justifications for this — through history or the concept of civil rights.

The development of these processes can be seen in the example of the following iconic celebrations.

1869. 300 Years of the Lublin Union

The anniversary was celebrated after reaching a constitutional compromise within the empire. This meant that, theoretically, the rights already existed, but practically they still had to be taken. Accordingly, the organizers' ambitious plans remained just plans. However, what they did manage to arrange was a creative rethinking of the events held in Lviv when Francis Joseph had visited the city.

Much more important was the transition from private to public celebration, as evidenced by the 1871 events taking place with the assistance of the City Council.

1880. 50th anniversary of the November Uprising

It was an interesting year, as the emperor had visited Lviv just before, the city authorities receiving him already in the role of organizers and not in that of mere executors of a program sent from Vienna. Besides, the day of the event was interesting as well. It was at the same time that the Ruthenians organized the anniversary of Franz II as the "liberator of Ruthenia." As he was the personification of pan-Germanism and centralism, nobody except Germans and Ruthenians celebrated this date.

In terms of ideology, an important turning point in this case was the attitude to the armed struggle and to the idea of insurrection. It was no longer considered a terrible mistake or tragedy (as it had been in the version of the Krakow conservatives). Now, according to the national democrats, it was an example to follow and a foundation for future accomplishments.

1883. 200 Years After the Victory at Vienna

Lviv was not the center of celebrating this anniversary. The tomb of King Jan III Sobieski was located in Krakow, so the attention of Polish society was focused there. There were events in Vienna that focused on the Austrian victories rather than on the help of Polish cavalry. The festivities in Lviv were one hundred percent loyal to the central government, and this allowed the demonstrations to "go out" to the Rynok Square and the Vysokyi Zamok Hill, not being limited to churches, closed halls, and small groups.

1888 and 1913. 25th and 50th Anniversaries of the January Uprising

Lviv became the center of Polish emigration from Russia after the defeat in 1864. On the one hand, it changed the political landscape and strengthened the position of the democrats. On the other hand, it began to oblige people to even greater participation in the cause of "preserving Poland." However, the 1888 events were rather small-scale and mournful in character.

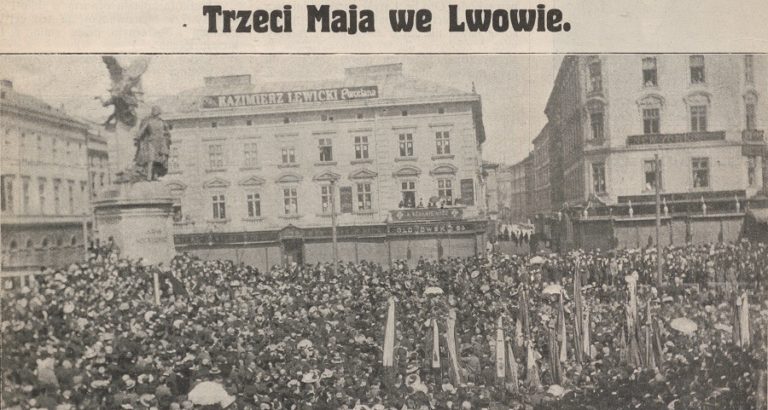

1891 and 1911. 100th and 120th Anniversaries of the Constitution of the 3rd May

As an idea for the celebration, the constitution suited everyone. Austria-Hungary was a constitutional monarchy, that is, it put the good ideas into practice, moreover, under the scepter of the best dynasty. And for the Poles, it was somewhere between failed uprisings and ancient victories. Vienna emphasized freedom and order, while Polish politicians highlighted the democratic principles of involving broad sections of the people in the creation of society.

1897 and 1907. Anniversaries of the Execution of Insurgents Wiśniowski and Kapuściński

These events demonstrate the development of the idea of "God, Fatherland and nation", which was promoted also through mass events in Lviv beginning from 1869. It was about martyrs dying for the people (in the broadest sense of the word) and certainly not about a tragic mistake. The effect was enhanced by the comparison of Lviv’s Mount of Executions with Calvary.

1910. 500th Anniversary of the Battle of Grunwald

Lviv was not the center of celebrations this time either. Since the representatives of the City Council and most of the activists went to Krakow, everything was surprisingly modest. However, the anti-German nature of the event itself should still have been presented as a "victory over the Crusaders."

* * *

Of course, the details are also important. When was the city's main church, the Latin Cathedral, involved, and when did people have to accept a worship in the Dominican Church? Were these celebrations held in a closed hall (even the City Hall) or was it possible to go out to the square? What do changes in priority locations look like compared to the emperor's visits? How did the perception of the same places change depending on the situation, for example, when the Franz Josef Mount became the Mound of the Union? After all, how did the color scheme change in the decoration of the city from the flags of the monarchy and the province to the national white and red flags? How did the illumination cards change, from the portraits of Francis Joseph to the pictures with the Polish eagle?

All these details, if one looks at them in development, provide an understanding of Lviv's public space evolution in the period of autonomy. From the 1860s to the beginning of the Great War, local elites, who used constitutional freedoms and ready-made imperial rituals as a model, managed to turn the city from the provincial capital into the symbolic "capital" of the Polish national movement.