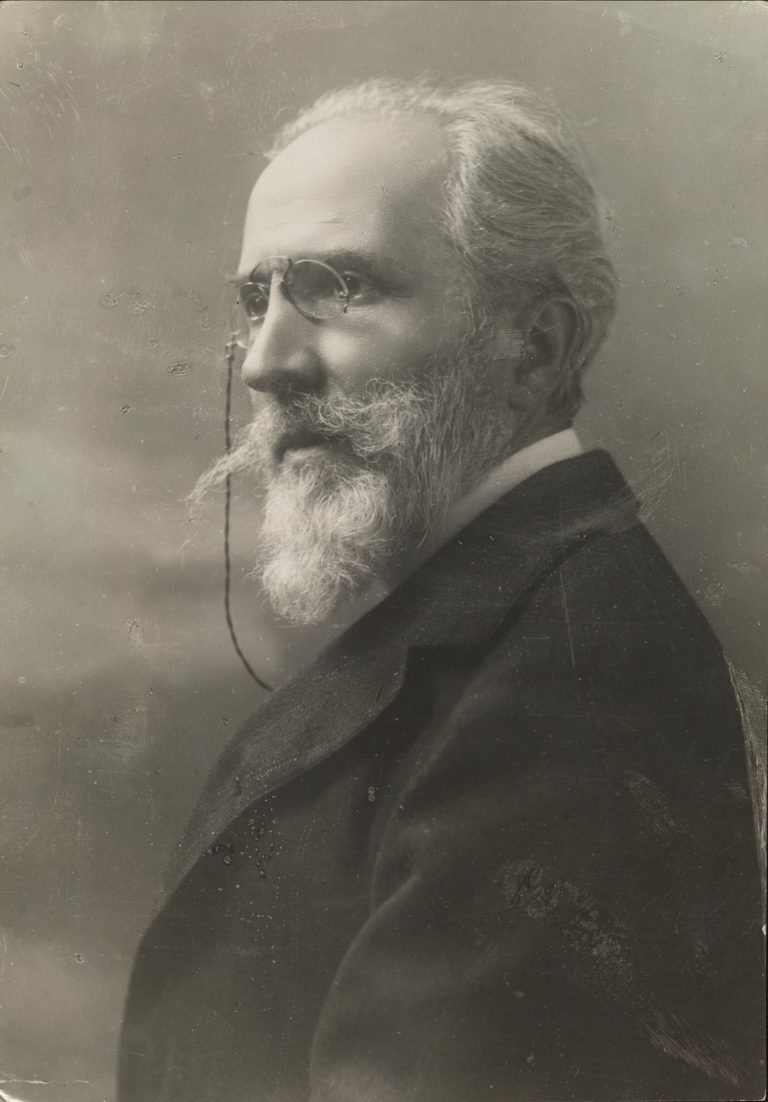

On 11 June 1913, Illia Dzhehala, a student of the teacher seminary, shot dead Karol Butkowski, a professor. This event, as well as the demonstrations it provoked, not only revealed the radicalization of young people and their desire to solve problems with a gun but also showed the trajectory of the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation.

The course of events can be reconstructed from the reports of the Polish patriotic press, which immediately "made the right diagnosis" — of course, from a nationalist point of view. This diagnosis was as follows: a Ukrainian student killed a Polish teacher. Although the killer himself denied any national motive for his actions.

Murder and detention

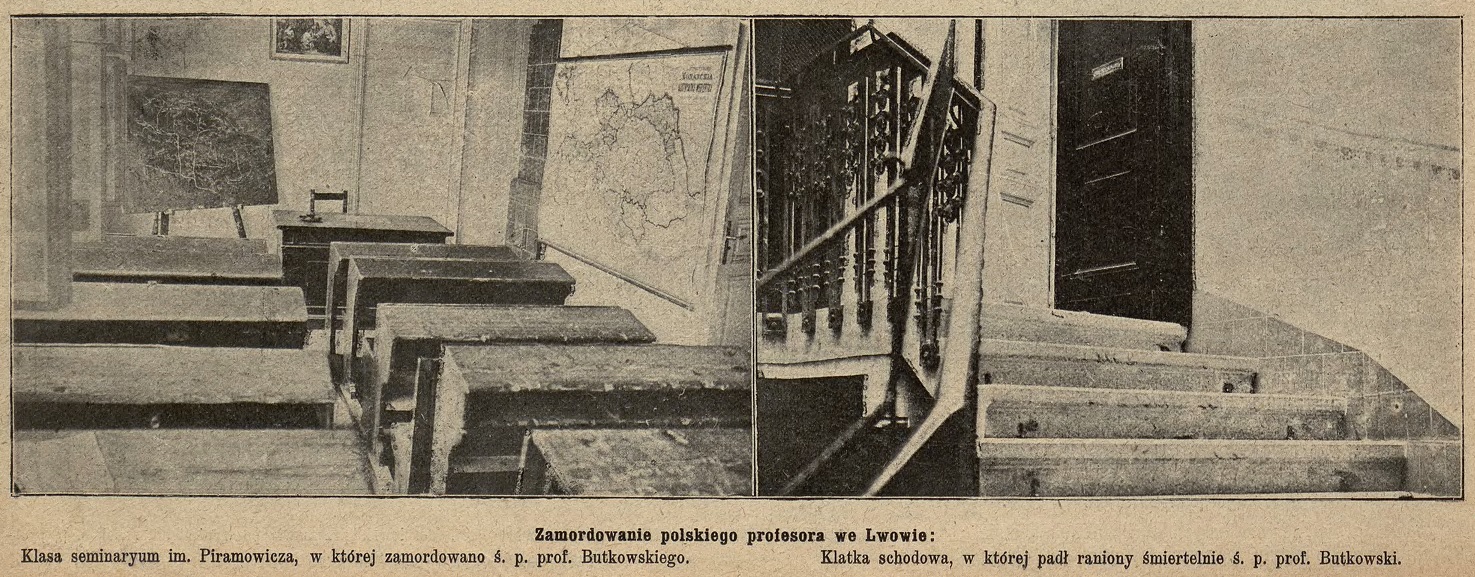

From 9 a.m., according to the schedule, Karol Butkowski, a 32-year-old Polish language teacher, was teaching at the Piramowicz City Teacher Seminary on ul. Nabieliaka (now vul. Kotliarevskoho). This time, Illia Dzhehala, a 19-year-old student, was not sitting on his seat, but near the door. At 9:45, when the lesson was over and the teacher was leaving the classroom, the student shot him three times in the back of the head and in the back, so that the victim's body fell into the corridor. Then he turned to his classmates, who allegedly wanted to detain him, shouted: "To the classroom!" and fired another shot at the wall, lightly wounding two classmates. He then hid himself in the kitchen on the same fourth floor.

Meanwhile, one of the students carried the wounded man, whose wounds turned out to be fatal, to the ground floor, panic breaking out in the school. Some of the students ran out into the yard and called a mounted policeman who was patrolling ul. Andrzeja Potockiego (now vul. Henerala Chuprynky), while others held the door to the kitchen where Dzhehala was hiding. The policeman first opened the door, but when he saw the killer with a revolver in his hands, he stepped back, pulled out his pistol, and then demanded that Dzhehala surrender and hand over his weapon. The latter calmly handed it over, and they went out into the corridor where the students were gathered.

The press reported that in this chaos, no one called the police by phone. The other group of police officers who arrived at the scene were called to a different address and for a different reason: they were told that someone had allegedly committed suicide. So the investigation was going on straight on the spot.

After a while, a crowd gathered in front of the seminary building, discussing the circumstances of the tragedy. When the murderer was taken outside, the crowd wanted to lynch him. They shouted, among other things, "the second Sichynskyi", threw stones and injured the detainee's nose and face. One of the policemen was hit in the head and the commissioner was threatened that if they wanted to take Dzhehala away by a carriage, the police would be beaten. The crowd demanded that he be taken through the city on foot. Therefore, he was led amidst the crowd to the police station on ul. Sadownicza (now vul. Antonovycha), where security was reinforced, and then he was taken to the police inspector's office.

Interrogation

During the interrogation, which lasted three hours, 19-year-old Illia Dzhehala justified his actions with personal revenge. He said that the professor had been biased against him, which is why his grades in his 3rd year of study deteriorated. Accordingly, Dzhehala was supposedly about to be expelled, and this was the decisive day. If the professor had questioned him and he had answered well, everything would have been fine. Although he had bought the gun a year and a half before, Dzhehala allegedly decided to kill the professor only last week. Accordingly, he sat down close to Butkowski so that the latter would notice and question him, and near the door so that he could kill him if he did not ask. In the end, the killer expressed regret that he had not shot himself while staying in the kitchen.

In addition, Dzhehala claimed that he had no friends, considered his fellow students to be 'materialists', and had not told anyone about his plans. He did attended the Ukrainian Sokil organization, but only for dancing. He read Shevchenko with no less interest than Sienkiewicz. Therefore, he denied that the murder of the professor was revenge on ethnic grounds.

Nevertheless, the police conducted searches of his relatives and friends, developing a version of the "execution of a Polish professor by Ukrainians" in which Dzhehala was only the executor.

Motives and the press

After the first interrogation, even the Polish press recognized that Illia Dzhehala did not look like a mentally healthy person. He seemed to be a loner, alienated from his family and peers, traumatized by the prospect of expulsion from the seminary.

Despite this, Polish newspapers still promoted the topic of "Ukrainian terrorism" as the main motive for the murder. Firstly, it conveniently lined up with other examples of national confrontation as another "shooting in an educational institution." Secondly, the mentally ill killer was supposedly unable to act entirely on his own, let alone think through such details as sitting near the exit and waiting for the victim to turn his back.

The fact that things were not as simple as Dzhehala described was also proven by his age. A person under the age of 20 did not face the death penalty. At most, he faced imprisonment from which, as the newspapers wrote, he could be helped to escape, as it had been with Myroslav Sichynsky before.

In the end, since the patriotic public did not like the version of a domestic murder, and there was no direct evidence of a Ukrainian conspiracy to execute the Polish teacher, the newspapers were filled with reviews of the Ukrainian-Polish conflict. They stated that the death of the Polish literature teacher was allegedly caused by the Ukrainian literature, press, political agitation, speakers at assemblies (viche) and gatherings, and the school system. In addition, the Polish press demanded that Ukrainian politicians call the incident a murder for political and national reasons. Ukrainians, logically, were in no hurry to make such statements.

The Polish press, after the obligatory references to Sichynskyi's murder of Potocki, threatened with future terror against the clergy and school teachers. "Who can be sure of the safety of their lives east of the San River?" the publicists asked rhetorically when Ukrainian "propaganda of act" led directly to the anarchy of the "times of Honta and Zalizniak." However, this was either ignorance or deliberate manipulation as even radical Ukrainian rhetoric did not contain calls for anarchy.

Meanwhile, Illia Dzhehala consistently denied any connection with the Ukrainian movement. He was not a member of any associations and did not attend any meetings. He used to come to the Sokil only for dances, and the last time was a year before. And he had not even heard about the recent conflict between Ukrainophiles and Russophiles near the dormitory on ul. Kurkowa (now vul. Lysenka), when there was a shooting as well. He had not talked about the murdered Karol Butkowski with other students, although he agreed that the latter was biased against Ukrainians.

The press published all these testimonies in good faith, but the tone of articles, such as "the killer denies…", made it clear that the newspapers did not recommend believing him. As soon as the following day, a version appeared that Dzhehala could have been taking revenge for another student, Chorniy. The latter committed suicide after being expelled from school a year before. This happened because he was distributing leaflets about Sichynskyi, and Butkowski exposed him. Accordingly, the Ukrainian students allegedly sentenced the professor, and Dzhehala became the executor. This version was supposedly supported by circumstantial evidence: one of the students said that he was not afraid of bad grades in Polish literature (which was interpreted as "the dead man would not be able to give a grade"), someone allegedly heard Dzhehala say that the revolver was "waiting for its time, it will be a great thing."

After the murder

Polish students declared mourning for their "beloved teacher", who, in their opinion, "treated Ruthenians fairly". The very fact that students used the term "Ruthenians" in 1913 suggests that it was not just a matter of love for the murdered professor.

Instead of studying on the following day, the Poles gathered in front of the seminary building to prevent the Ukrainians from entering. Police lined up between the two groups of young people to prevent a new conflict. The rally of Polish youth ended only when the Ukrainian students left, the administration announced a week-long break in classes, and officials promised to establish a separate educational institution for Ukrainians.

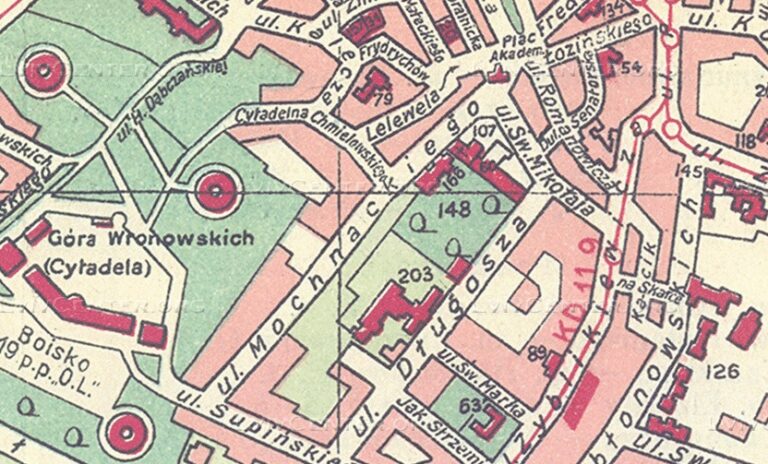

Meanwhile, it turned out that even a bad grade in Polish literature could not be the reason for Illia Dzhehala's expulsion, while the situation in other subjects was really threatening. It seemed that the motive was a Ukrainian conspiracy, but searches in the Ukrainian dormitory on ul. Mochnackiego (now vul. Kotsiubynskoho) yielded nothing again.

The Ukrainian Academic House on ul. Mochnackiego (now vul. Kotsiubynskoho). Source: Museum of Ethnography and Arts and Crafts

Further politicization

Naturally, after the murder, the press published a lot of materials about the problems of coexistence between peoples, revenge, and the radicalization of young people. The latter, according to Polish publicists, "resorted to shooting too often". There were also generalizations like "savagery", "politicization of education", "young people do not listen to professors", etc.

Obviously, the most comfortable situation was for those who immediately took the position of "a Ukrainian murderer against a young Polish professor." From this perspective, everything was clear and logical. For those who tried to preserve opportunities for understanding with Ukrainians it was more difficult, as well as for the Ukrainians themselves.

Firstly, Ukrainian newspapers could not write about Dzhehala too critically without alienating their audience. Secondly, unlike the Potocki murder, this time it was possible to really put everything down to an isolated incident and easily distinguish between the "Ukrainian public" and the "act of an individual." Then the problem was no longer Ukrainian-Polish relations but rather the education system shortcomings, the student's mental state diagnostics, the behavior of individual teachers, and so on.

Threats by the Polish youth

On Thursday, 12 June 1913, about 1,500 Polish students gathered in the Czytelnia Akademicka (Academic Reading Room) premises. Although there was no permission to hold a student assembly, and the police stopped the event, the students "managed to vote" to condemn the "bestiary act of the Ukrainian Dzhehala" and to invite the public to the funeral of their teacher; that is, they said basically everything they intended to say. In addition, the appeal to the Ukrainian youth was interesting: if the Ukrainians did not decisively condemn the murderer, the Poles would consider it a manifestation of solidarity with the criminal.

The students of the teachers' seminary were even more outspoken: they publicly promised to "fight against Ukrainian provocations" and "protect Polish teachers from Ukrainians."

It is therefore not surprising that the police were on full alert in those days, keeping order both during the funeral and in places where students gathered.

Friday, 13 June: the funeral

"A huge demonstration in honour of the man killed on duty": these were the words used in Polish newspapers to describe the event. There were reports about several thousand people in front of the deceased's house alone, not counting those who joined later. In addition to the educators who honoured their colleague, the Vice President of Lviv, Tadeusz Rutowski, was present, choirs sang, and speeches were delivered. In other words, it was a massive and pompous event, but almost without the participation of representatives of the political authorities.

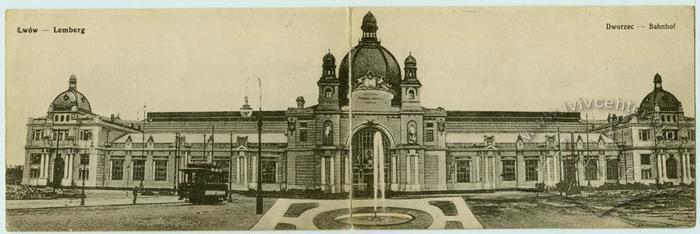

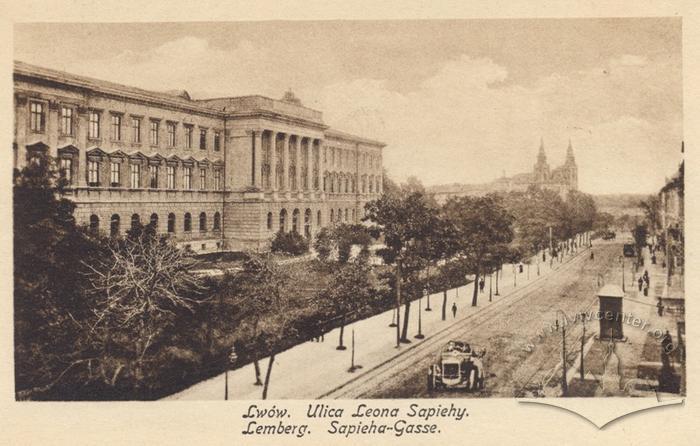

The procession took almost five hours to reach the railway station from Kochanowskiego Street (Butkowski was to be buried in Krakow, from where he had come to Lviv). The route passed through ul. Pańska, ul. Batorego, pl. Halicki, pl. Marjacki, ul. Kopernika, ul. Sapiehy, and ul. Gródecka.

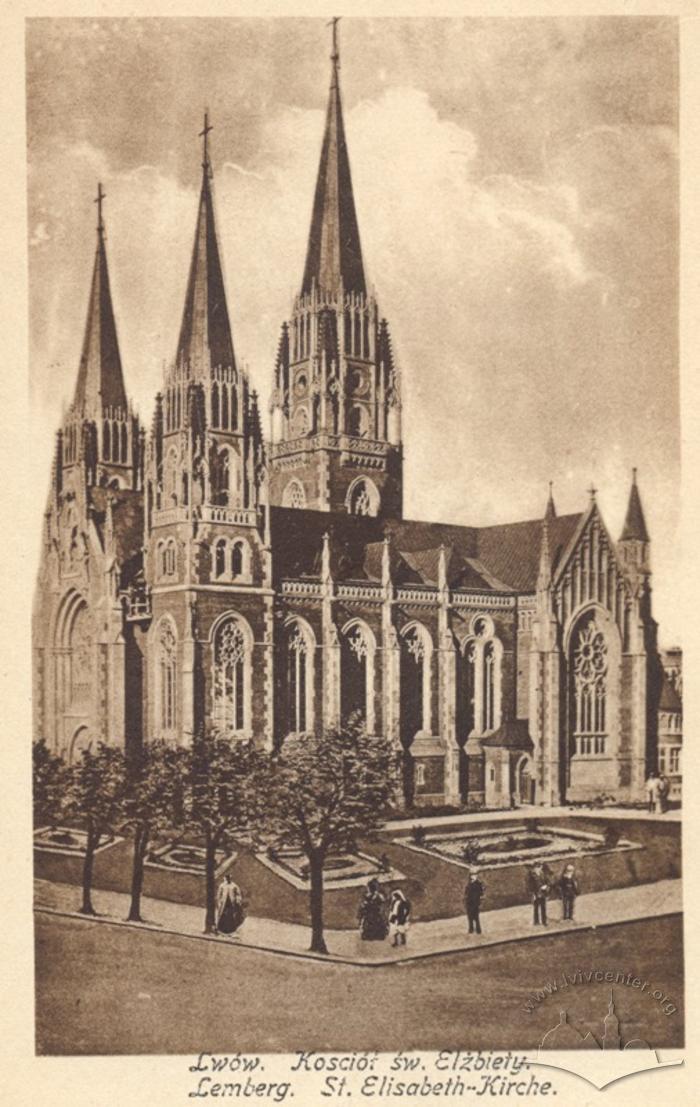

Along the way, the procession stopped at the Mickiewicz monument, a traditional point for patriotic demonstrations. The second stop was at the turn to ul. 29 Listopada (now vul. Konovaltsia), near the boarding school (dormitory) of the Piramowicz Teacher Seminary. The third stop was the church of St. Elizabeth, from where the clergy came out to meet the procession on pl. Bilczewskiego.

Among the wreaths carried behind the coffin was one made of thorns. Such a symbol of martyrdom was brought, for example, to the graves of the fallen striking builders, as well as to the Execution Mount to the Polish rebels' memorial. This left no doubt that the shot professor had died "for the Polish cause."

The coffin was carried from the church to the railway station on the mourners' shoulders. The teachers and students spoke about service to the nation and homeland, about a life laid on the altar of the cause, about social ideals and savagery, about a heroic death for the sake of a better future for the people, and even about the position of a teacher as almost a military one.

After the funeral

On the same day, a second youth assembly was held, which lasted until 10 p.m. On the one hand, the participants seemed to be appealing to the authorities; on the other hand, however, they promised (or threatened) to defend national interests in educational institutions themselves. To do so, they asked for "moral support" from society.

On the following day, Saturday, a mourning service was held at 9 a.m., again in the church of St. Elizabeth.

Classes at the Teacher Seminary resumed on Tuesday, 17 June. However, Polish youth gathered in front of the building and demanded that Ukrainians not be allowed in while the investigation was ongoing. The newly appointed director agreed to significant concessions, and the 3rd year Ukrainian students were forced to leave the institution.

The student committee announced the creation of the Karol Butkowski Foundation to provide scholarships, but exclusively to Poles. In other words, the instrumentalization of the event was in full swing.

On the other hand, the authorities, represented by the Provincial School Board, although sympathetic to the Poles, tried to resolve the conflict. It was announced that the Ukrainians living in the dormitory had dissociated themselves from the murderer, and that everyone had "made peace" and "returned to the common table." The public was also informed that Ukrainian teachers, like their Polish colleagues, did not take into account the nationality of students.

This was very appropriate, because June in Lviv was not only a time of exams, but also a period when Sokół/Sokil societies held training, meetings and performances in the city. Therefore, the threat of clashes between young people from different organizations was very high.

The trial was scheduled for autumn, and it was decided to conduct a psychiatric examination by that time in order not to delay the proceedings.

Other assessments

Of course, the tone in the assessment of Butkovski's murder was set by the Polish patriotic press. This time, however, the government-run Gazeta Lwowska was demonstratively restrained. It reported on the murder of the professor without judgment or emotion, without mentioning his nationality or even describing the funeral.

The Ukrainian press, primarily the Dilo, which was later cited by other newspapers, tried to simultaneously support the version of the accused, Dzhehala himself, without failing to remind the readers of the enmity between Ukrainians and Poles. They wrote that the motives for the murder were purely personal and that the professor was unfair and biased. At the same time, though, they wrote that the Polish professor was mocking a poor Ukrainian student, who did not belong to the Ukrainian movement and did not support it, but it was worth remembering about the student Chorniy's suicide a year earlier.

The murder at the teacher's seminary shows the level of radicalization and militarization of young people in Lviv by 1913. Even if the murder was not an "execution," it demonstrates how the general background of conflict and hatred affected individuals.

It also shows how easy and understandable it was for the public to accuse all Ukrainian students of being co-responsible. Young people in educational institutions, teachers, and the police seemed to be prepared for this development.

It can also be clearly seen how well everything was worked out in terms of political mobilization in 1913: meetings, resolutions, assemblies, processions, routes and stopping points. At the same time, the police managed to keep the situation under control with minimal interference, compared to previous years.