In 1912, the Russian Duma decided to separate the Kholm/Chełm Land from the Kingdom of Poland and to turn it into a separate province. This decision led to mass riots in Lviv, protests against the tsarist policies, conflicts with the police during an attempt to break through to the building of the Russian consulate in Lviv, and the burning of portraits of the tsar and the heir to the Russian throne during a rally near the Adam Mickiewicz monument.

The events of May 1912 are an example of mass politics of a new type in Lviv, when organized groups (chiefly youth political societies) became the driving force behind protests, joined by increasingly large masses of ordinary participants. Traditional political rituals were also changing: the classic assemblies (ukr. viche) of the late 19th century were supplemented by spontaneous marches, clashes with the police, and spectacular events like the burning of the tsar's portrait.

In this case, the reaction of Lviv's political circles to the events in the Russian Empire is significant. Lviv once again confirmed its unofficial status as the "Polish Piedmont", which, thanks to more liberal Austrian legislation, "guarded" Polish interests in Russia and Germany. Moreover, in this case, it was possible to appeal to international law and agreements signed, among others, by the Austrian government. After all, the Congress Kingdom of Poland was a product of agreements signed in 1815 by the powers that had defeated Napoleon and not the result of Russian policy alone.

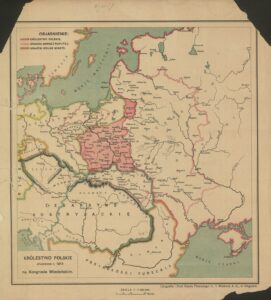

The Kholm/Chełm Land and the Congress Kingdom of Poland

From 1815 onwards, i.e. after the Congress of Vienna, the part of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth incorporated into Russia was called the "Kingdom of Poland." In the official Russian nomenclature, the term "Tsardom of Poland" was preferred, while in Polish, the term "Królestwo Kongresowe" or "Kongresówka" was used at the everyday level. Over time, especially after the unsuccessful Polish uprisings, the Russian government significantly curtailed the Kingdom's autonomy, which was reduced to literally nothing by the turn of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, the separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land from the Congressional Kingdom was perceived by Polish society as an extremely negative event. As it was presented in the press of that time, this decision opened the way to further Russification of the local population and the "loss of the region to Poland", especially after the Union of Brest was abolished there in 1875, with all existing Uniate parishes annexed to the Russian Orthodox Church.

On the eve of the riots. May 1909 protests against the separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land

Lviv politicians were always interested in the situation in the Kingdom. Therefore, even talks or plans to separate the Kholm/Chełm Land became a pretext for political protests in Lviv. For example, in May 1909, when Lviv traditionally celebrated May Day and the anniversary of the Third May Constitution, events dedicated to political proceedings in the Russian Empire were also held.

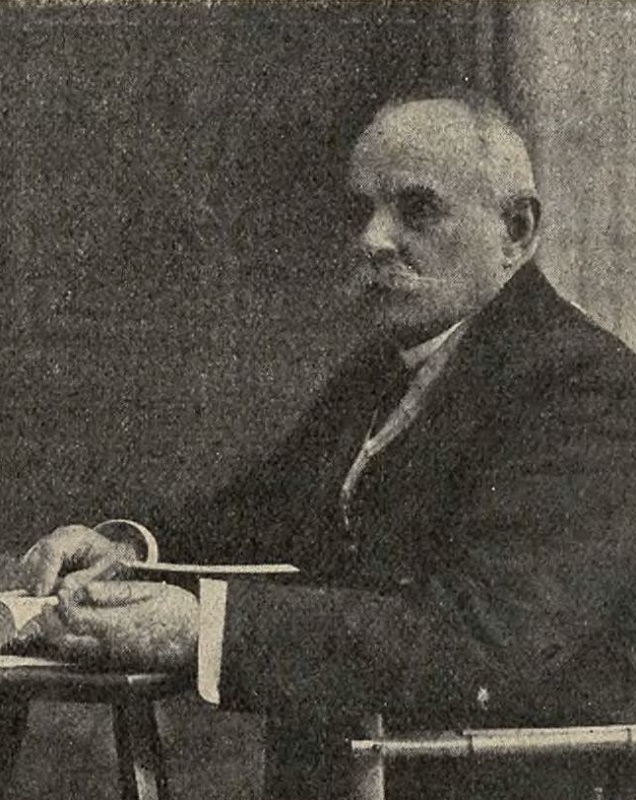

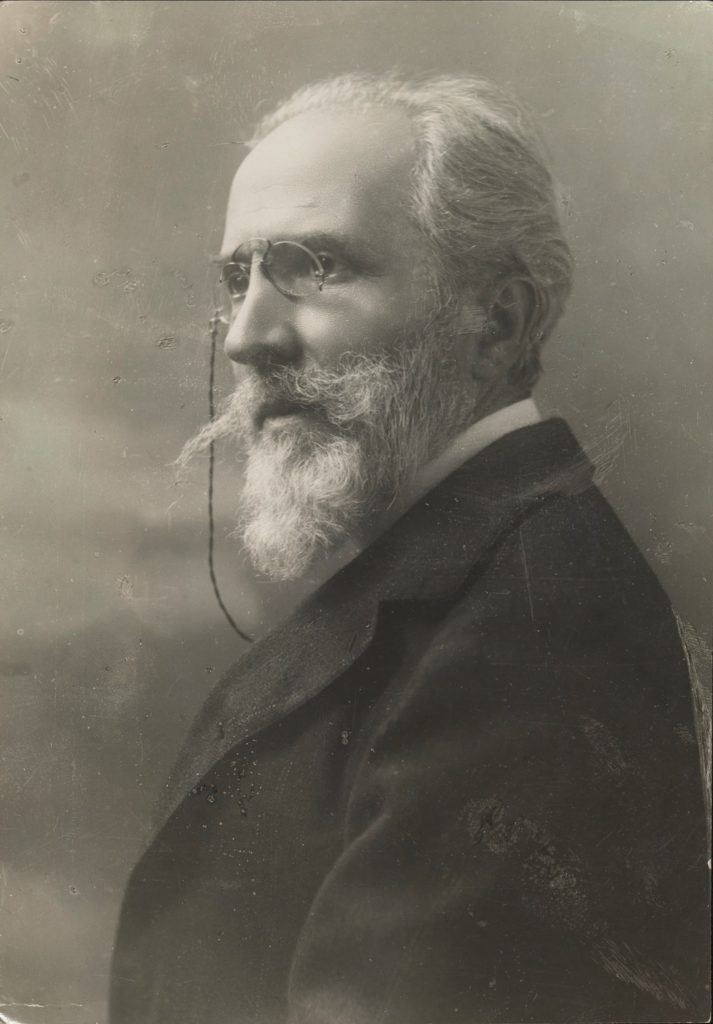

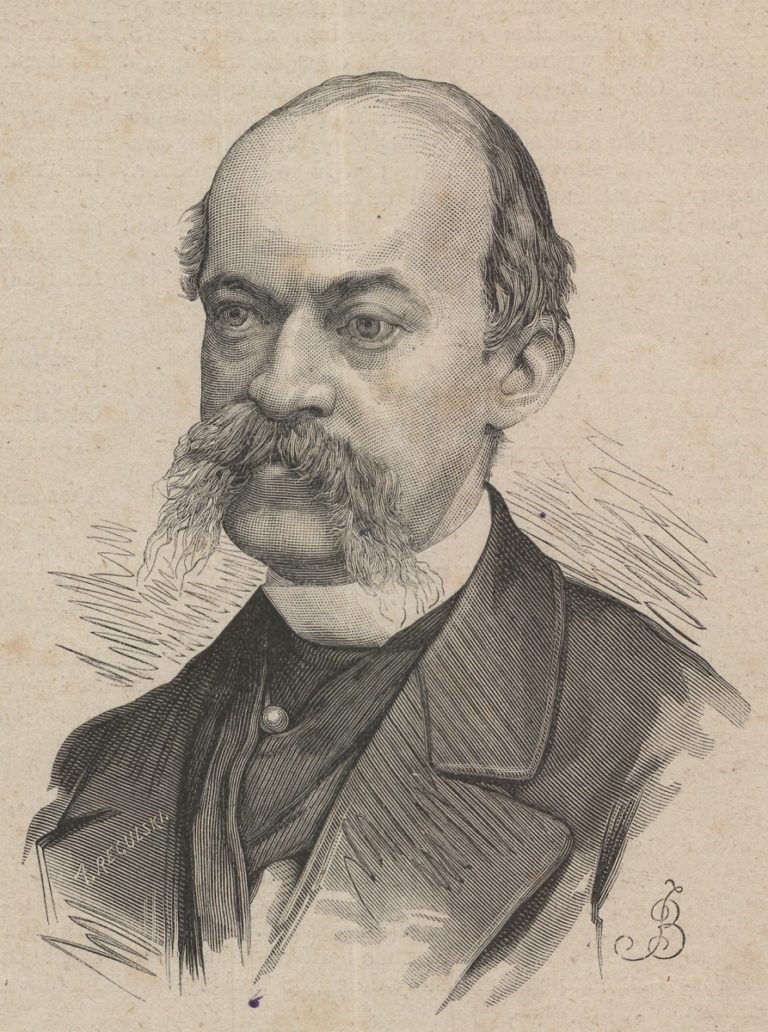

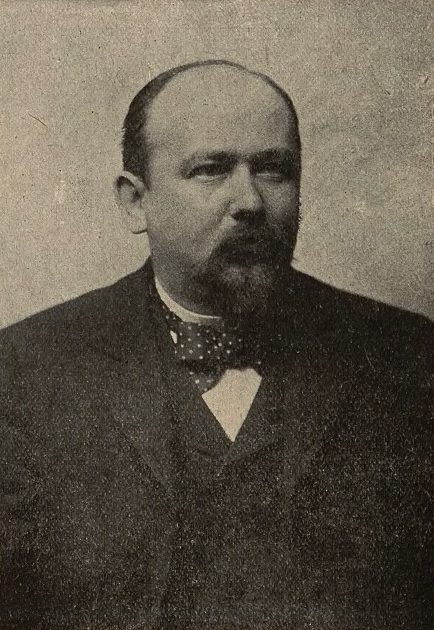

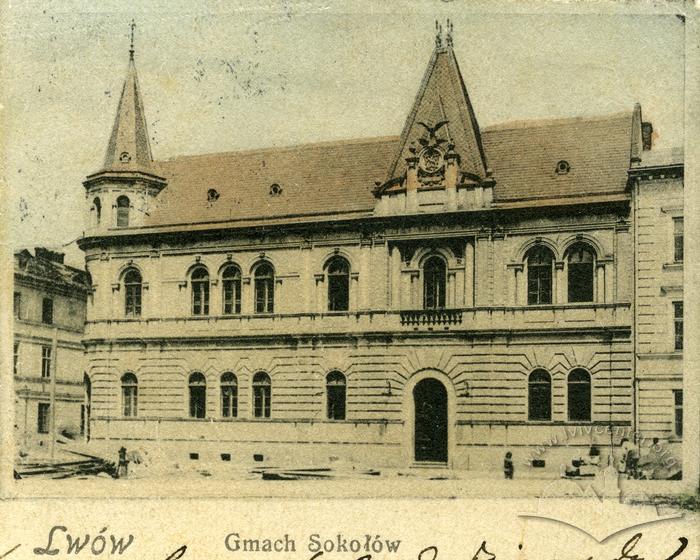

On 2 May 1909, at 6 p.m., people of "all social classes and political groups" gathered in the city hall courtyard, many listening to speeches through open windows inside the city hall building. At 7:30 p.m., Wojciech Biechoński, a member of the City Council, addressed his "compatriots" saying that the Russian government, indulging the wildest instincts of Russian society, had decided to tear the territory of the Kholm/Chełm Land "away from the body of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth." Therefore, the task of the entire Polish society was to respond to such attempts. Tadeusz Rutowski, Vice President of Lviv, spoke in the same spirit. He also appealed to the international community and to the right of peoples to develop their own national identity. After the assembly resolution was read out, the crowd marched to the Adam Mickiewicz monument and dispersed. Similarly, the Sokół May celebrations of that year ended with an appeal to the Polish Circle in the Austrian Parliament regarding the Kholm/Chełm Land case. Subsequently, similar appeals were adopted by various student organizations.

- Войцєх Бєхоньський / Wojciech Biechoński

- Тадеуш Рутовський / Tadeusz Rutowski

In other words, the problem of separating the Kholm/Chełm Land into a separate province had been discussed for several years, and the Duma's decision of 1912 was only a catalyst for unrest.

The demonstration on 11 May 1912 and clashes with the police

On Saturday, 11 May, when it became known that the Duma had decided to separate the Kholm/Chełm Land from the Kingdom of Poland, a rally of many thousands gathered in the centre of Lviv, ending with a march to the Russian consulate and bloody clashes with the police.

People started gathering near the monument to Adam Mickiewicz at 7 p.m. The core of the protesters were students. As of 7:30, the number of protesters, according to various estimates, reached from 1 to 8 thousand people. They concentrated on pl. Mariacki and ul. Karola Ludwika, started singing "Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła" and unfolded a banner reading "Niech żyje niepodległa Polska" (Long live independent Poland).

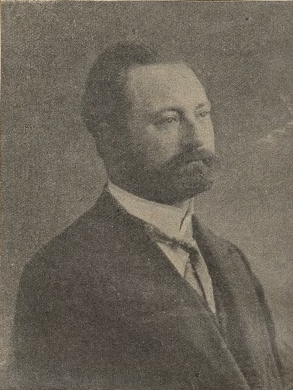

Two speeches are worth noting here. The co-editor of the Kurjer Lwowski newspaper, Jan Dąbski, said that half a million "Poles on ethnographically Polish lands had been cut off from the Kingdom of Poland and given to Orthodox priests and officials" and that "the 'Polish Golgotha' of 1875 was being repeated" (in 1875 the Union of Brest was abolished). Therefore, in Galicia, where Poles felt freer, they had to support those who lived in the Kholm/Chełm Land, including financial support, and, most importantly, to prepare for the struggle for an independent Poland, which would be created mainly by conscious workers and peasants in the future.

After singing the hymn "Z dymem pożarów", one of the students spoke on behalf of the socialist academic youth. His speech was even more radical; in particular, he said that it was time to engage in real military training for the "future repulse of the tsarist regime."

Then the situation began to spiral out of control. Singing the song "Oto dziś dzień krwi i chwały", the crowd occupied the entire street, so that traffic was effectively blocked. Students with a purple standard led the column and moved towards ul. Jagiełłońska. Here, they were met by the police (about 50 people), who were, though, unable to stop the crowd, as the command ordered them not to use their sabres.

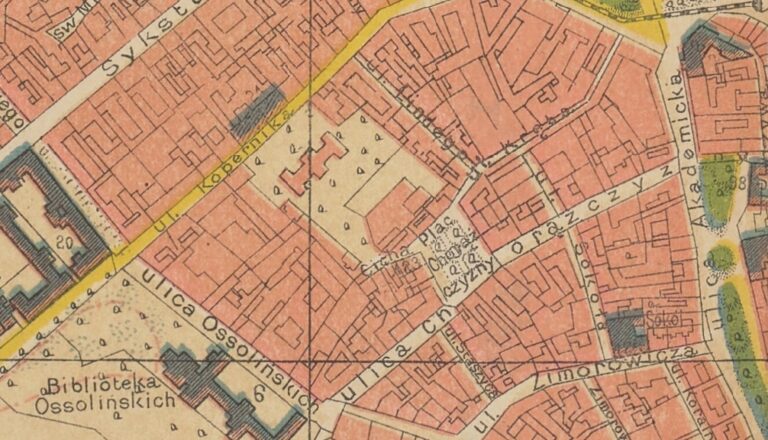

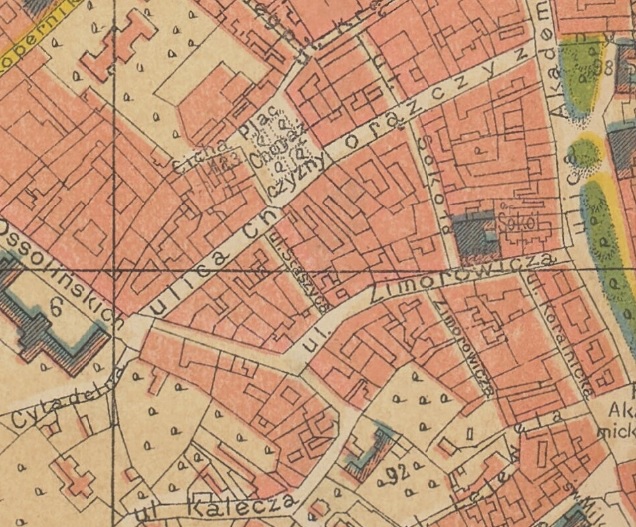

The protesters (again, according to the maximum estimate, there were already up to 10,000 people, while the police, through the loyal press, claimed to have 1000) marched across ul. Jagiełłońska, then to ul. Marszałkowska and ul. Słowackiego. Ul. Kopernika was securely blocked by the police, so the column turned to ul. Ossolińskich, ul. Chorąszczyzny, ul. Akademicka and returned to the Mickiewicz monument. From there, they turned onto ul. Karola Ludwika and ul. Kopernika so that the police were now behind the column. So the demonstrators were able to quickly walk up the street towards the Russian consulate building. Ul. Andrzeja Potockiego, a few dozen metres from the consulate, was blocked by another police cordon, reinforced by a 10-man cavalry unit.

Before reaching the Russian consulate, the demonstrators began chanting "shame", "onto the lamppost" and other offensive things. At the same time, according to the patriotic press, they did not attack the police and did not provoke them in any way. Nevertheless, cavalrymen with naked sabres moved into the crowd cutting protesters. They were followed by police officers on foot (about 50 people), also with bare sabers. As a result, 30 people were injured, three taken to the hospital with serious injuries. The demonstrators retreated but still remained there for about an hour, shouting offensive slogans not only at the Russian consul, but also at the police.

Doctors arrived at the clash scene and helped those injured in the premises of Brukner's pharmacy (at what is now vul. Stepana Bandery 21) and in the Polytechnic vestibule. Particular attention was drawn to the fact that many of the injured had wounds on their backs, this indicating that the police had abused their power. The President of Lviv, Józef Neumann, immediately arrived at the scene from the Strzelnica and, after examining pools of blood and scattered hats and caps, guaranteed the students his support and promised to contact the Director of Police, Józef Reinlender.

The Kurjer Lwowski newspaper noted an unfortunate phenomenon: during the riots, the watchmen of the surrounding townhouses locked the gates and not only did not help students escape from the police but also refused to help the injured. Even in Warsaw, as the newspapers wrote, there was no such inhuman treatment, although the watchmen often cooperated with the tsarist police.

A separate episode of the evening was an attempted pogrom of the editorial office of the Russophile magazine Prikarpatskaya Rus at ul. Ossolińskich 11. During the clash near the Russian consulate, some students were on ul. Ossolińskich. The editorial office was located in the courtyard, and the students had already broken the windows when the police arrived. Fearing that the police would close the gates and they would be trapped, the protesters ran out into the street. They even won over one of their comrades detained by the police.

Around 10 p.m., the situation on the streets calmed down, and the block around the Russian consulate was controlled by the police.

"After the massacre": impressions and explanations

Obviously, the violent dispersal of the Polish patriotic rally made a strong impression on the people of Lviv. Even the press, which was loyal to the central government, first wrote about the excessive use of force by the police and switched to a more "official" version only later. The official version was that about 1,000 aggressive young people had provoked clashes with the police. They kept assuring the police commissioner who was at the rally that they had no intention of picketing the Russian consulate. After circling the center of the city, they suddenly started running in the direction of the consulate until they met another police unit. The latter acted "without any special instructions from their superiors", solely within their authority, using cold steel only when they saw wounded and contused people among them. 13 police officers were hit in the head with stones, while others sustained minor injuries. As for the student who was won over by his comrades near the editorial office of the newspaper Prikarpatskaya Rus, it was a routine check of documents, so the student was released.

Of the thirty injured protesters, three were taken to hospital. The press wrote that one of them (a Polytechnic student) was wounded with a sabre in the face, but his eye was not injured. Another was injured in the knee with a bayonet, but there was no blood poisoning. The third one had to undergo surgery under general anesthesia, and of his several wounds, the most threatening was the wound on his arm, which might have to be amputated.

On Sunday, the following day, a "deputation" from patriotic and workers’ organizations, 20 people in total, gathered to see the city president. They talked about "Polish citizens of Lviv, the shed Polish blood and the police who did not value this blood." They also said that the townspeople's patience would not last forever, so the city was facing more serious unrest. This was the message that the president of Lviv was to deliver to the governor after the meeting.

In addition, Polish members of the Austrian parliament raised the issue of the police adequacy at the level of the State Council and the government. Eventually, the victims announced their intention to demand financial compensation.

The consequences of the conflict in terms of ideology were more global. The goal of drawing Vienna's attention to the Kholm/Chełm Land case was achieved. In addition, the Poles of Lviv demonstrated their solidarity and willingness to help their compatriots from the Kingdom of Poland and the Kholm/Chełm Land.

Moreover, nationalist Polish politicians started to talk not just about defending the "Polish proprietorship" but about a "new Polish expansion in the East." In this future expansion, the leading role was assigned to Lviv, a city "on the borderlands" where "civic honour" demanded that they reconsider their relations with those "who run the police", that is, they began, in a veiled way, to make claims to the Austrian administration. The only thing that spoiled the idyllic picture of the "national uprising" was the irresponsible position of the owners and watchmen of the townhouses around the Russian consulate.

Act Two: students, parliamentarians, and the City Council.

Student protests, now against police brutality, spread to other cities as well. Students in Krakow, for example, also gathered at the Mickiewicz monument and smashed the windows of a newspaper office. This time, it was the moderate Czas newspaper, for its "biased" article about the Lviv clashes with the police.

In Lviv, on Wednesday, 15 May, the newly established 'Kholm Committee of Polish Youth' (pol. Komitet chełmski młodzieży polskiej) organized another demonstration. The 'Committee' included students of different ideological preferences: nationalists from the Czytelnia Akademicka society, supporters of independence from the Kuznica society, and the progressists and socialist supporters of independence from the Życie society. In the morning, they distributed leaflets against Russian policy in all educational institutions. At noon, students from the University, the Polytechnic, the Veterinary Academy, the School of Forestry and the Agricultural Academy in Dubliany filled the courtyard of the Polytechnic. Here, in the atrium, they opened an assembly and formed a column of about 2000 participants to march to the Mickiewicz monument. Walking along ul. Kopernika, ul. Słowackiego, ul. Trzeciego Maja, ul. Jagiełłońska, and ul. Karola Ludwika, they sang patriotic songs. They carried two banners in front of them: a purple one from the Kuznica society reading "Niech żyje niepodległa Polska" ("Long live independent Poland") and a red one from the socialist youth.

Due to censorship, the speeches of the leaders of student societies were not included in the press publications. They spoke about the need to prepare for a war with Russia and the futility of the agreement policy.

After a rally at the Mickiewicz monument, about 500 students gathered near the Kuznica society on ul. Ossolińskich, where they demonstrated for a while longer. The Russian consulate was guarded by the 30th Infantry Regiment and a unit of lancers.

The piquancy of the situation was that the Kuznica society building was located next to the editorial office of the Prikarpatskaya Rus magazine. Therefore, the police had locked the gate and did not let the students into the courtyard. The latter were content to tear off the editorial office's information sign from the façade.

Meanwhile, Polish parliamentarians appealed to the Minister of the Interior. They reminded him that the borders of the Kingdom of Poland were defined in 1815 and approved by Vienna as well, so Russia's unauthorized revision of them violated international agreements. The role of the Russian consulate in Lviv as an "incubator" for spies and Russophiles was also recalled. Finally, the inadequacy of the police in dealing with peaceful protesters was not forgotten either.

Against the background of the conflict, the political nature of the City Council was fully revealed. President Józef Neumann, in addition to his statements about police brutality, said many interesting things. For example, he said that in times of defeat and loss, many people could not control their emotions (and it is worth mentioning here that the events described took place against the backdrop of a sharp confrontation with Ukrainians over the fate of Lviv University). Moreover, he maintained that Polish patriots found a way out in marches and demonstrations and that Poles in Lviv felt oppressed because they could not influence the decisions of the Russian Duma. In such a situation, the City Council asked the government to make the police "municipal" instead of "military" if it was impossible to make it more humane in any other way.

The Ukrainian newspaper Dilo initially limited itself to reprinting the official announcement, neither criticizing nor approving of the protesters' actions. The report briefly described the event itself "through the eyes of the police": around 800 students gathered at the call, the editor of the Kurjer Lwowski newspaper Jan Dąbski spoke, the protesters, their number grown to 1,000, set off on a march, assuring the police commissioner that they did not plan to picket the Russian consulate; later, however, they attacked the police, who had to defend themselves, and so on. Later, the Dilo noted that further protests in Lviv and Krakow began not because of the Kholm/Chełm Land case, but because of the actions of the Lviv police.

The official position was supported by both Russophiles and Christian social movement members from the periodical Ruslan. However, it went as far as condemning the demonstrators for involving schoolchildren in a fight and vandalizing the editorial office of the Russophile newspaper.

The position of Ukrainian politicians regarding the Kholm/Chełm Land was that it was not only a Russian-Polish conflict, but first and foremost a Ukrainian-Polish conflict. After all, the only Russian thing in this area was the church, while "ethnographically" the Kholm/Chełm Land was considered Ukrainian. Therefore, the point was not the "separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land" but its "accession" to the territory of "Russia-run Ukraine." This meant that the decision of the Russian Duma had to be welcomed, despite the fact that Russification was not better than Polonization.

With Russophiles, things were simpler: they rejoiced at the "reunification of Russian lands" and wrote that "the Russian population of the Kholm/Chełm Land could now look forward to the future."

Act Three. The burning of portraits of the tsar and the heir to the Russian throne.

On Sunday, May 19, there were two assemblies, which later merged into one. In the morning, the socialist youth gathered near the Polytechnic from where they went to the city hall at 10:30. The assembly, which called for "both male and female workers and comrades" to come, was held in the city hall courtyard. It discussed future actions regarding the "separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land and against the anti-Polish initiatives of the Prussian government," thus touching upon broader issues of national politics. Polish politicians Józef Hudec and Otto Hausner, as well as Ukrainian social democrat Teofil Melen, spoke at this gathering.

On the same day, at noon, an assembly gathered in the hall of the Mother Falcon society on ul. Zymorowicza. It was announced as "a meeting of delegates from all Polish societies, a demonstration of the provincial capital and the first voice", which was to be the beginning of protests throughout Galicia. Representatives of the Polish national movement from the Kholm/Chełm Land attended as well. Even peasants from the surrounding villages arrived; among the politicians were Józef Gudec, who was already mentioned above, as well as Eugeniusz Romer and Stanisław Głąbiński, professors of Lviv University. The latter took part in the march to the Mickiewicz monument later.

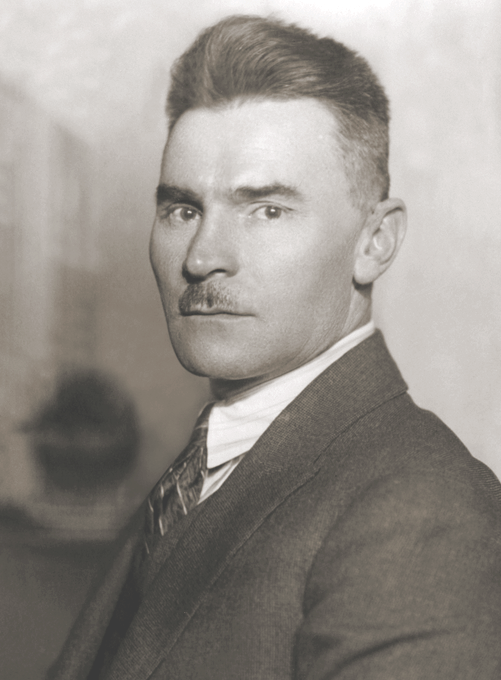

The main report on the situation in the Kholm/Chełm Land was read by Dr. Jan Kasprowicz, a poet. He accused the Russians, the "Orthodox Black Hundreds," of "tearing a piece out of the body of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth." He also spoke of the Uniates, who were forcibly Russified and converted to Orthodoxy, and did not miss the opportunity to mention the Galician Ukrainians who, against this background, decided to cleanse the Greek Catholic rite of Latin layers (this was a dig at the Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky and his policy of "Byzantinization" of the Greek Catholic Church).

However, the speakers did not stop there and raised issues of a much more global scale. For example, they habitually talked about Lviv, which was now called "the guardian of Poland in the East" and "the volcano of Polish patriotism." They discussed the future of Poland after its partition between the empires. It was stated that the Buh River, after the separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land from the Kingdom of Poland, had ceased to be the border between Russia and Poland, so it was necessary to expand activities to the further eastern territories.

It turned out that the Polish "Society for the Care of Uniates", which operated in the Kholm/Chełm Land, expanded its profile and was now the "Society for the Defence of the Eastern Borderlands." At the same time, Lviv, using liberal Austrian legislation, was to become the legal headquarters for all Polish activists from Russia and Germany. A charitable foundation ("Dar Chełmski") would be established here to support the Polish underground in Russia, which would accumulate funds from Poles around the world. It was immediately decided to form a committee for the future foundation and to appeal to the Roman Catholic "patriotic bishop" of Lviv, Władysław Bandurski, to support this initiative with his authority.

Meanwhile, the socialist assembly participants moved from the city hall to the building of the Mother Falcon society. They sang patriotic songs, and when the assembly in the building was over, they all marched together, singing "Jeszcze Polska", down ul. Akademicka to the Mickiewicz monument. Independentist youth with a purple banner headed the march, followed by ordinary Lviv residents and then by socialist youth with a red standard. On the square near the Mickiewicz monument, they sang the 'Song of the Legions', and several speeches were delivered, one ending with the words 'Forge weapons' (pol. Kujcie broń).

When the protesters were singing the anthem "Z dymem pożarów", a portrait of the Russian tsar and a portrait of the heir to the throne "appeared" and were set on fire by "someone" to the applause of the crowd. The patriotic Polish press emphasized that this happened the day after Tsar Nicholas II's birthday.

At that time, the Russian and German consulates were guarded by reinforced military units, and many soldiers patrolled the streets in the city centre. Therefore, after burning the portraits, the crowd dispersed peacefully.

Consequences

Naturally, the rallies in support of the indivisibility of the Kingdom of Poland did not change the plans of the Russian government. However, they did have a serious impact on the political situation in the Polish movement in Galicia.

Firstly, although Lviv remained "a stronghold of the Polish spirit in the freest part of Poland", its "mission" began to change as the very tasks of Polish nationalists were changing. Instead of "defending the proprietorship", they began to talk about "expansion" (at least cultural expansion) even further east, and Lviv, which was now located on the "borderlands", was to play an important role here.

The idea of the police also changed. The Polish press wrote about the "shedding of Polish blood" in a quite different way comparing to what was reported during the violent dispersal of the Ukrainian demonstration in 1905. Now the idea of a "civilian guard" gained new relevance, and the president of Lviv spoke of the need for reforms, of subordination of the police in Lviv not to the central government in Vienna but to the City Council. Students began to speak out about the "Russian methods of work" of the Lviv police, which recruited informants from among patriotic and socialist youth. They asked for publicity and help from the management of educational institutions.

The burning of the portraits helped to achieve the main goal of the action, i.e. publicity. Now the attention of ministers and consuls was focused on the case, so the issue of the Kholm/Chełm Land (and in a broader sense, the entire Polish movement) came to the fore again.

Obviously, all of this was the result of the active participation of young people in political processes "on the street." This helped not only to mobilize the masses, but also to increase the degree of tension during the confrontation.