The anniversary of the January Uprising is an important date for the Polish national movement. Given the political situation and the level of freedoms in different parts of the divided Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (German, Austrian and Russian), it is natural that the most favorable conditions for celebrating such anniversaries were present in Galicia. It remained necessary to adhere to what was allowed and to take into account censorship here as well, although the latter was significantly weakened in the late 19th — early 20th century.

History

The Polish January Uprising broke out on January 22, 1863 and lasted in the territory of the Russian Empire during 1863-1864. It was the most massive and proclaimed the most democratic slogans as compared to the previous ones (both the Kosciuszko and the November Uprising). Nevertheless, it ended in defeat like the previous attempts to gain independence. As a result of the Russian government troops' victory, hundreds of insurgents were executed and thousands were deported to Siberia.

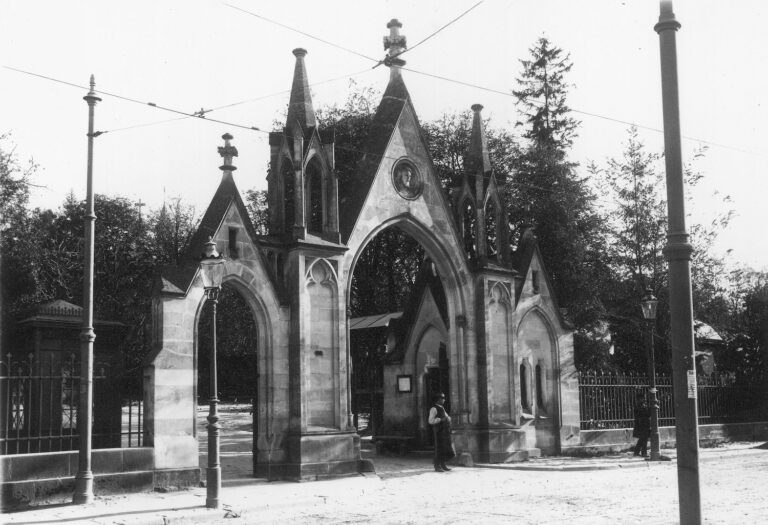

Many participants in the uprising found refuge in Lviv, the period of their active political life coinciding with the period of autonomy in Galicia. The insurgents were actively involved in political processes, this being another factor in strengthening the role of democrats and weakening the position of the Krakow conservatives. While initially Austrian Lviv was seen by the Polish political emigrants as a place where there was relatively more freedom (compared to Russia or Prussia), later a large number of Polish revolutionaries present began to "oblige" the city to demonstrate an increasingly radical position. This is how the idea came about that "Lviv should set an example for the rest of Poland." The image of the Polish fortress was complemented by a separate "insurgent necropolis" at the Lychakivskyi cemetery, where about 230 veterans were buried throughout the period of autonomy.

Celebrations in Lviv in 1888

In 1888, when the 25th anniversary of the uprising was celebrated, the position of the conservatives was still strong. Accordingly, discussions continued about the uprising itself: whether it was heroism or a tragic mistake and irresponsibility. Besides, the government's policy did not encourage mass celebrations. Therefore, the program of events in January 1888 was limited to a mourning service in the Latin cathedral and a solemn dinner at the City Casino.

During the service on January 21, 1888, weapons were placed on a symbolic hearse, while a youth choir sang patriotic songs, like it was during the commemoration of the November Uprising. About 300 people (including veterans and some invited youth) gathered for dinner at the City Casino. In addition to the dinner, money was collected for charity, patriotic songs were sung; among the toasts, there were mentions of the insurgents of 1831 and 1848 as well as of the participants in the 1863 uprising sent to Siberia.

The celebrations of 1913

The celebrations of 1913 were much larger, stretching both in time (throughout the year) and in the urban space. They were organized and coordinated by the Society for Mutual Aid of the Participants in the Uprising of 1863 (pol. Towarzystwo Wzajemnej Pomocy uczestników powstania z r. 1863). In addition, it was a time when the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation escalated against the background of the general militarization of society.

For two days on the eve of the feast itself, January 19 and 20, 1913, assemblies were held in the halls of many institutions, societies, and organizations. These meetings included theatrical performances for children, music programs, historical lectures, and political speeches. Choir rehearsals also continued in the Lutnia Hall at the Skarbek Theater.

On January 21, at 4 p.m., wreaths decorated in "national colors" were laid at the Lychakiv cemetery. It was a demonstration of several thousand, which was attended by members of various societies, students, and surviving veterans of the uprising. The scouts held lighted torches, sang national anthems and marching scout songs. The speeches delivered at the cemetery were mostly about "our rights," as well as about those killed "by Moscow bullets and on the gallows in Warsaw, where it is forbidden to honor them today." Thus, by criticizing only the policy of the Russian Empire, it was possible to maintain loyalty to the Habsburgs while declaring "national rights." Afterwards, the veterans, scouts, and students with torches went to the "city," namely to the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. Here again, a short rally was held at which the politician Witold Lewicki spoke.

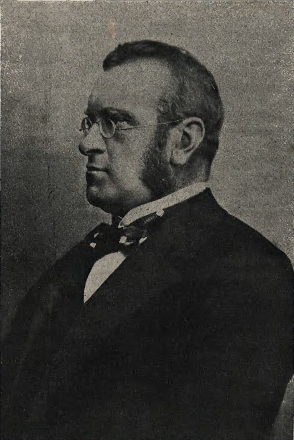

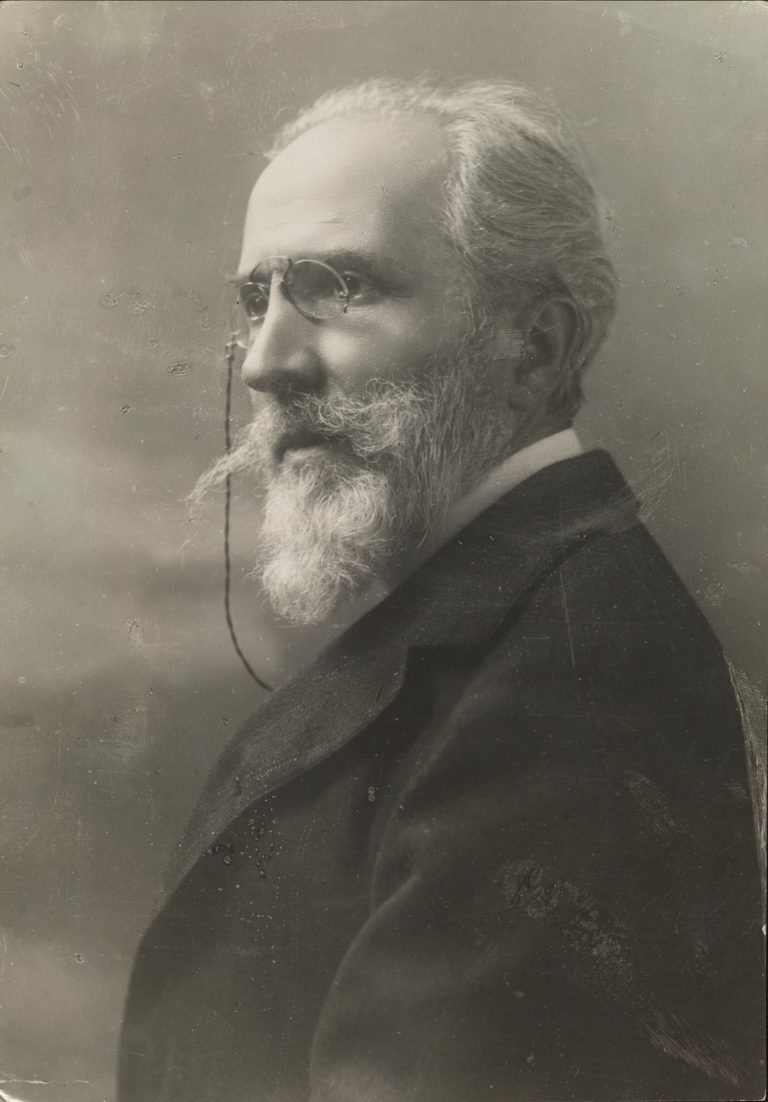

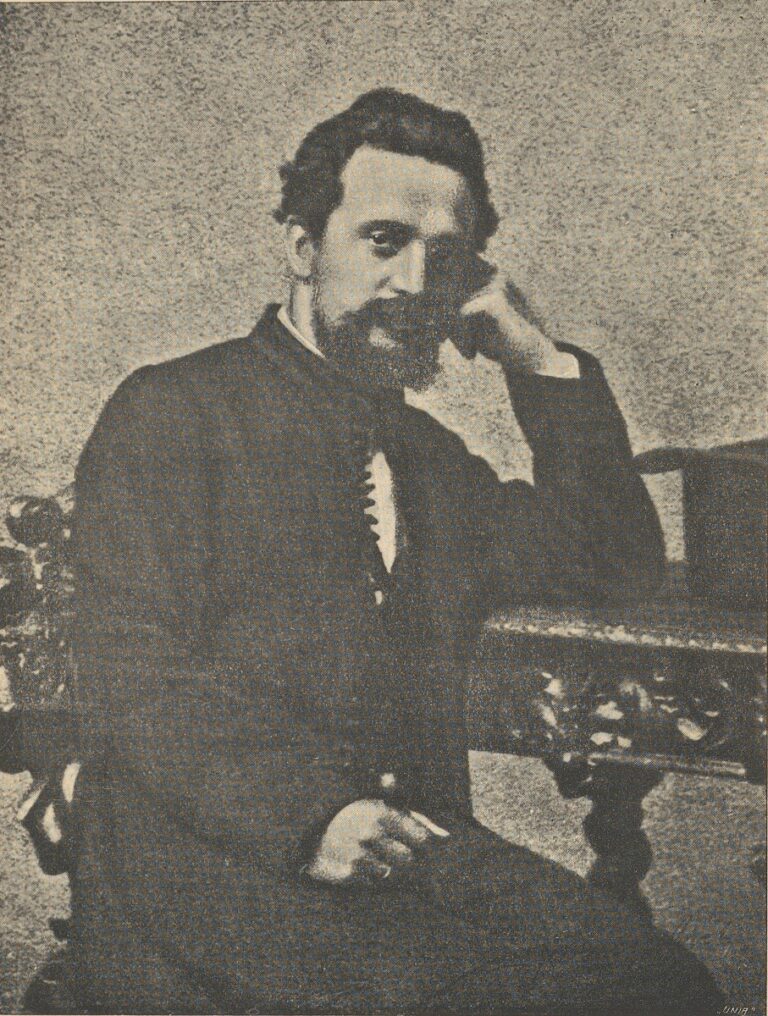

At 8 p.m. on the same day, a reception in honor of the veterans began in the City Hall. The hall was decorated with artifacts from 1863 (including weapons) provided by the Jan Sobieski Museum. In total, the dinner was attended by more than 250 guests, including about 100 veterans of the uprising, as well as members of the City Council (wearing kontuszes), the Latin and Armenian archbishops, university professors, members of the Galician Diet, members of the Society for the Protection of Veterans and other dignitaries. Ludomir Benedyktowicz, a participant in the 1863 uprising, and Józef Kajetan Janowski, secretary of the National Government at the time of the uprising, were seated in the two most honorable positions alongside Józef Neumann, the President of Lviv. The guests toasted for Lviv, which received the emigrants ("the children of Warsaw became the children of Lviv"), and for the "ideals of independence"; traditionally, greetings from emigrant insurgents who had settled abroad were read.

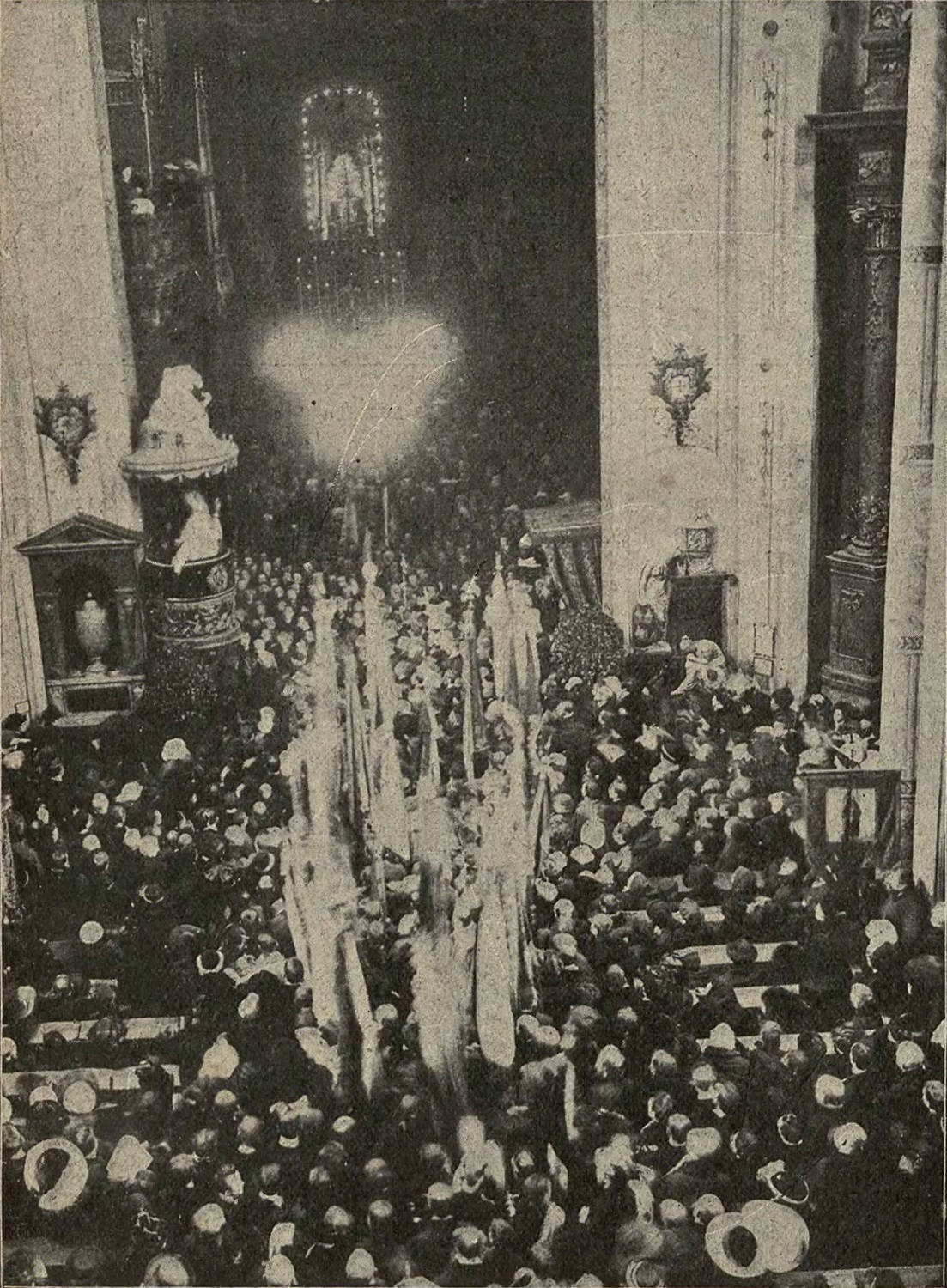

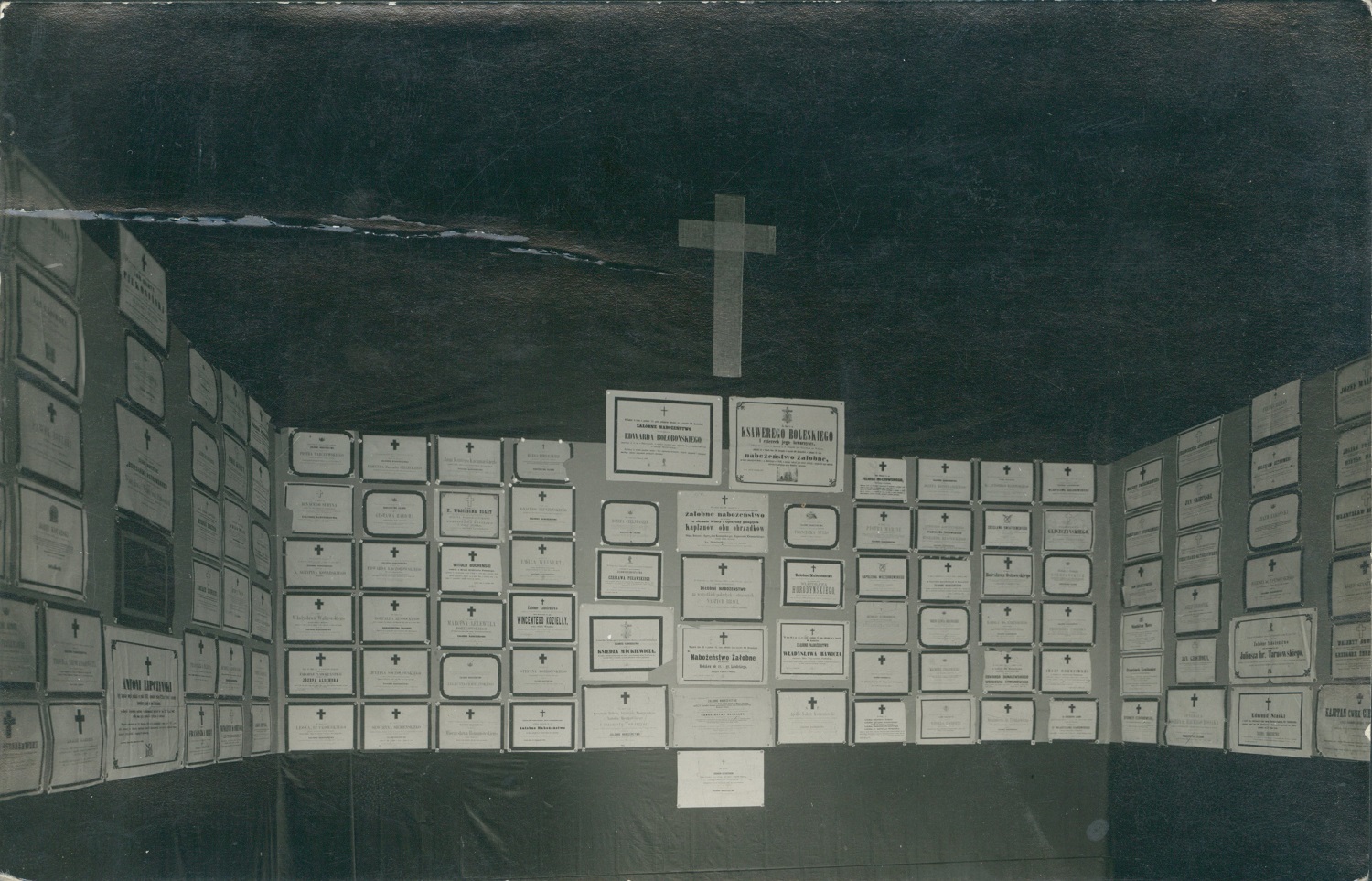

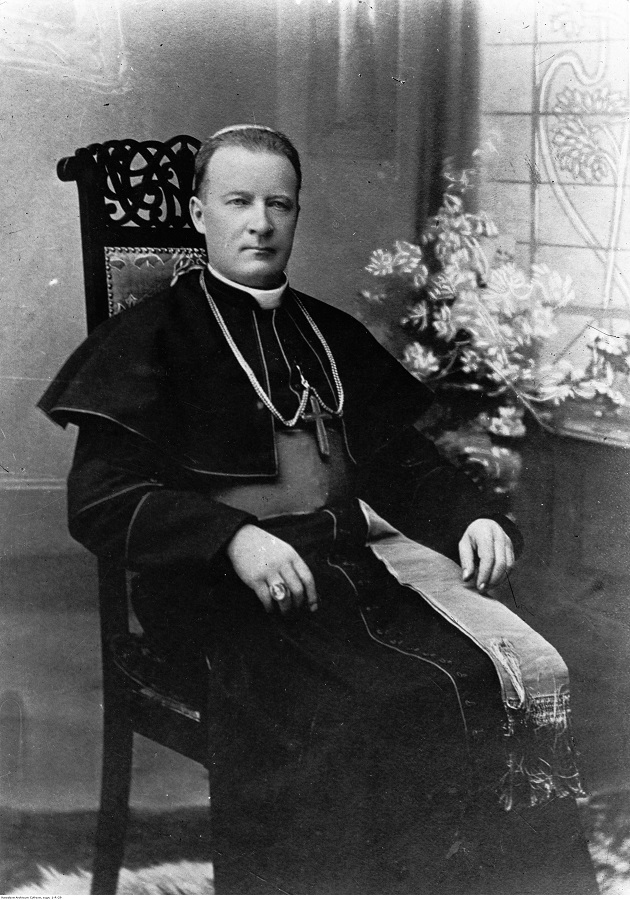

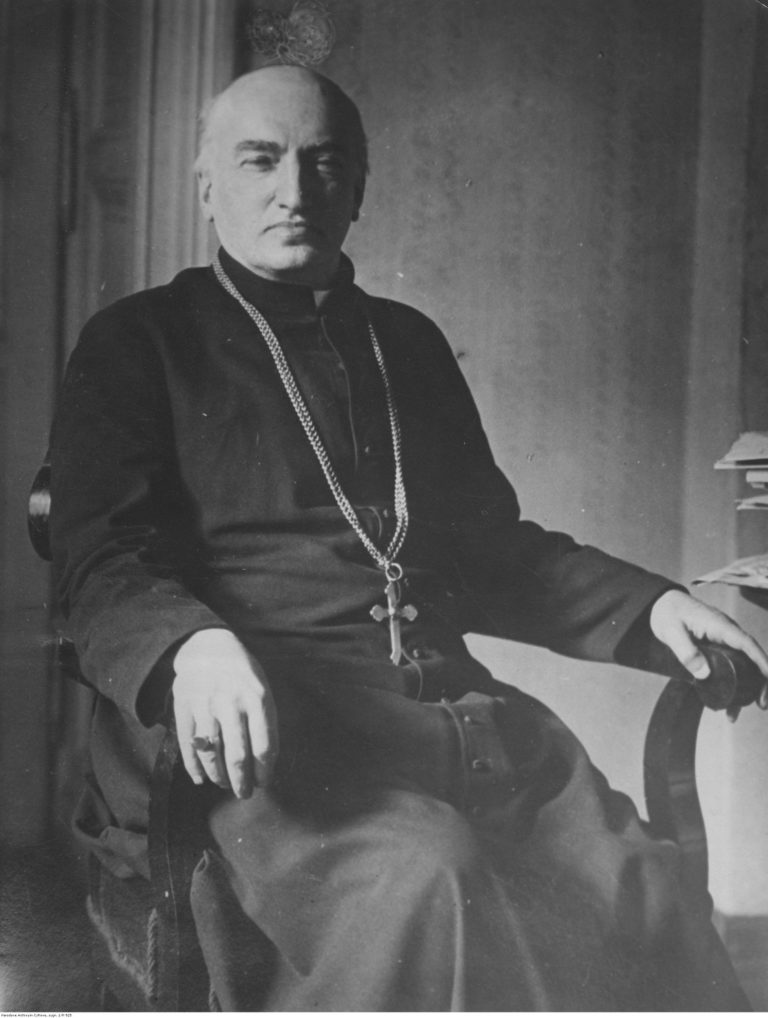

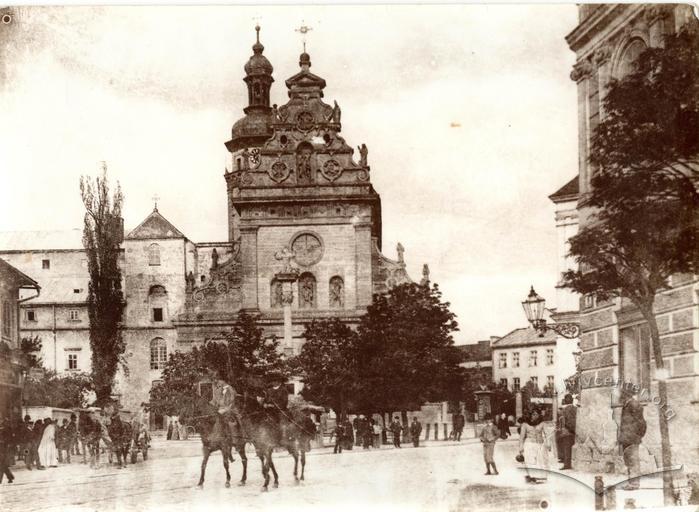

On January 22, solemn services were held in the Latin cathedral and in the synagogue in the Zhovkivske suburb (Temple). In the cathedral, with the participation of two prelates: Józef Bilczewski, the Latin archbishop, and Józef Teofil Teodorowicz, the Armenian archbishop, this time there was not a mourning service, but a solemn one, in the "intention of the national cause." The press described the events at the cathedral as a "demonstration in the church" and a "prayer for the national cause" that many people were not able to attend because the church could not accommodate all who wanted to be there. Among those present were Count Adam Stanisław Gołuchowski, the Provincial Marshal, Józef Neumann, the President of Lviv, Tadeusz Rutowski, the Vice President of the city, deputies of various levels, professors of the University, leaders of numerous societies and organizations. In addition to the singing of patriotic hymns, usual in such cases, a fundraising was held in the church for the benefit of the veterans. Shops and offices were traditionally closed at that time.

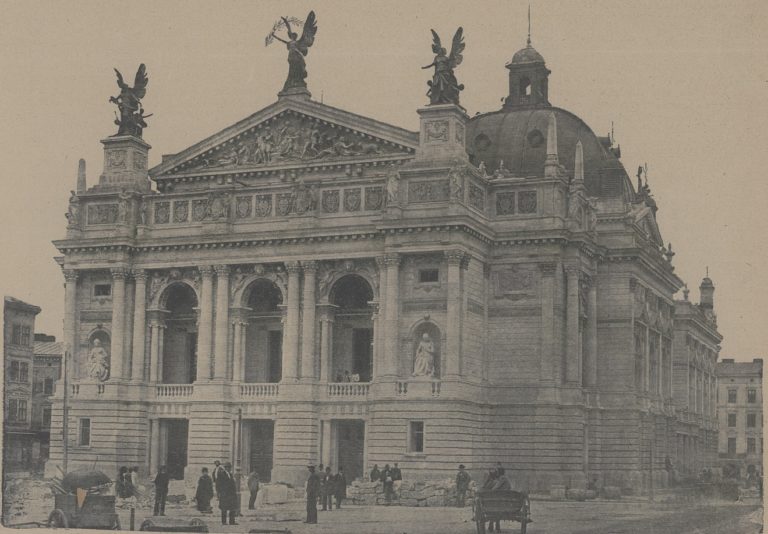

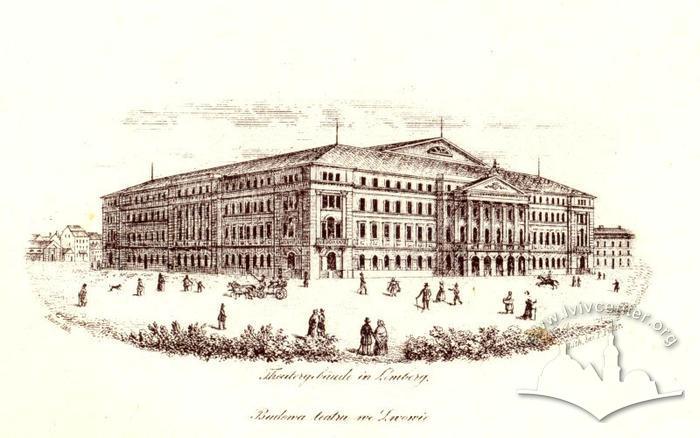

At 12 o'clock a festive procession started from the Latin cathedral to the City Theater, where a solemn assembly began an hour later. The march to the theater was led by the "falcons" (members of the Sokół Society) in field uniforms, followed by several dozen veterans. Then there were workers, members of various societies, young people and so on. There were even socialists with red banners. In front of the theater, the "falcons" "saluted" the participants in the uprising (which was a clear allusion to the traditional greeting of the emperor by grenadiers).

At 4 p.m., a festive meeting of the uprising participants began in the City Hall. Admission was free; that is to say, censorship, verification, or registration of participants, as was the case in the 1880s, was already out of the question. There were no personal invitations with which the police had controlled "unreliable" citizens. The main element of the meeting was the speech delivered by Józef Janowski, secretary of the National Government at the time of the 1863–1864 uprising.

In the evening there was a performance at the City Theater (which, again, can be considered a "borrowing" from the practices of receiving the emperor). The social democrats organized a meeting in the City Hall at 7 p.m., which was also free to attend. Politicians Józef Hudec, Mykola Hankevych and Buber spoke, the last two on behalf of Ukrainian and Jewish socialists respectively.

Anniversary celebrations throughout 1913

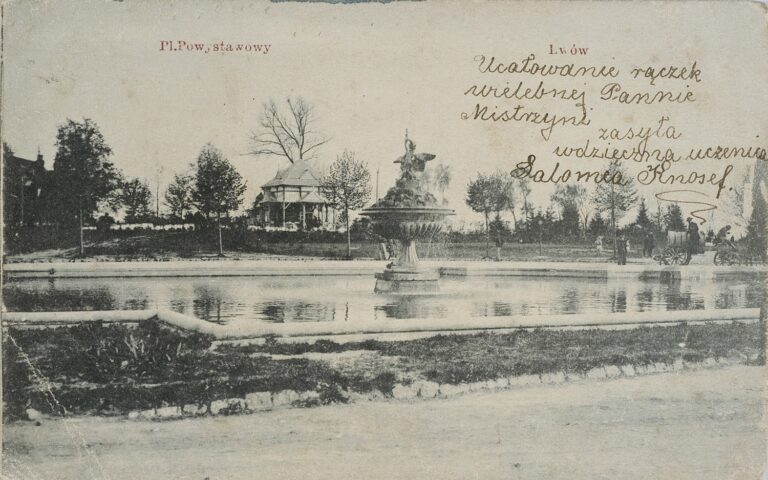

The celebration of the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the January Uprising lasted in Lviv throughout the whole year. A celebration organized by a local Mutual Aid Society (pol. Towarzystwo Bratniej Pomocy Słuchaczów Politechniki we Lwowie) took place on January 24 in the Polytechnic hall. The rally of the Polish Sokół Society, the exhibition dedicated to the uprising (on the so-called Exhibition Square), and the congress of Polish singers were timed to coincide with this date. In September, there were services in the Bernardine church and thematic evenings at various organizations and societies; thematic brochures and illumination cards were issued.

In general, the 50th anniversary of the January Uprising demonstrates an interesting trend: the Polish national movement, gaining more freedom within the empire, increasingly followed imperial rituals. Members of the Sokół Society in uniform served as an honorary grenadier guard, illumination cards with the image of the emperor were replaced by similar cards with Polish eagles and military attributes. The emperor's traditional charity for the benefit of the poor was transformed into fundraising for the benefit of the uprising veterans. Private houses and institutions were decorated for national dates, as during Franz Josef's visits.

Two locations appeared on the city map that were "obligatory" for national celebrations, namely, the City Theater and the monument to Adam Mickiewicz.

The peculiarity of this anniversary was the active participation of the left wing, as the uprising of 1863–1864 proclaimed democratic slogans and demands.