On May 3, 1791, the Extraordinary Sejm (Diet) of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth adopted a constitution. The first one in Europe and second one in the world (after the United States), it contained many norms that were progressive and democratic for that time. However, just a year later, in 1792, the third partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between Russia, Prussia, and Austria took place resulting in Poland's losing its independence. Since the second half of the 19th century, the 3rd of May has been a Polish national holiday. In the Habsburg Empire, it began to be celebrated after Galicia was granted autonomy.

The celebration itself was used as a mobilizing factor. On this day, politicians, officials, and members of various organizations, including paramilitary ones, actively reminded people of themselves. At the same time, it was necessary to declare loyalty to the ruling dynasty or at least not to exceed what was permitted.

Until the centenary (1891), celebrations in the times of autonomy were limited to church services. On the occasion of the 100th anniversary, large-scale events were organized, which then became more or less regular.

The ideology behind the celebration of the 3rd May Constitution Day

The meaning of the celebrations was obviously based on patriotism. There was, however, a difference between the moderate position of the current elites and the rhetoric of the national-democratic camp representatives.

The conventional "official" version, reflected in the government newspaper Gazeta Lwowska, was that the 3rd May Constitution was a wonderful example of progress without social unrest, demonstrations, or revolutions. From this, it was concluded that Polish national autonomy could effectively exist within Austria-Hungary, and that the celebration on the 3rd of May was a celebration of "freedom and order" for the benefit of "the people and the state."

Another version, the national-democratic one, highlighted a less optimistic picture. Although Galicia was not as bad off as the Russian or German parts of the divided Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, even here, "because of the stańczycy (the Western Galician conservatives — trans.) and their allies," Poles could not develop in the economic, political, and cultural areas normally. That is why it was so important to mobilize society through various demonstrations. The date of the 3rd of May itself is somewhere between the days of victories (e.g. the Battle of Grunwald, the campaign of Batory and Żółkiewski in Muscovy, or the Battle of Vienna) and defeats (such as the commemoration of the 1831 and 1863 uprisings). It also contained an important practical element — a call to involve the bourgeoisie and peasantry in politics.

Polish democrats (unlike conservatives) criticized the development of the province under Austrian rule. In particular, they claimed that, through industrialization, cities and towns were not developing but simply growing due to an increase in the number of soldiers and officials. Therefore, the 3rd of May was another opportunity to remind society of the importance of the cities’ and towns’ economic and social development. This led to the need to abandon the traditional idea of the nobility exclusivity. Moreover, this need was not seen as a consequence of Austrian reforms but as a natural process, already enshrined in the May Constitution.

Rituals and symbols

On the eve of the 100th anniversary of the constitution in 1891, the organizing committee issued a proclamation appealing to the patriotism and solidarity of "all residents of Lviv." The proclamation stated, in particular, that a "civil guard" would maintain order in the streets, so any clashes or riots on that day would be evidence that society was not ready for self-government. Therefore, "in the interests of the entire nation," the committee asked the residents of Lviv who "cherished the honor of the Polish name" to maintain order. In other words, the concepts of "residents of Lviv" and "Polish nation" were virtually synonymous in this case.

Society prepared for the anniversary in advance through the activities of various organizations. For example, the Polytechnic Society was to publish textbooks in Polish, entrepreneurs donated to orphanages, and funds were raised to purchase patriotic works of art. Even at the May Day workers' meeting, which took place in the courtyard of the city hall, it was decided to take part in the celebrations of the 100th anniversary of the constitution. Shop, factory, and café owners were urged to close their establishments on that day. Homeowners were asked to decorate their façades and to light candles in the evening.

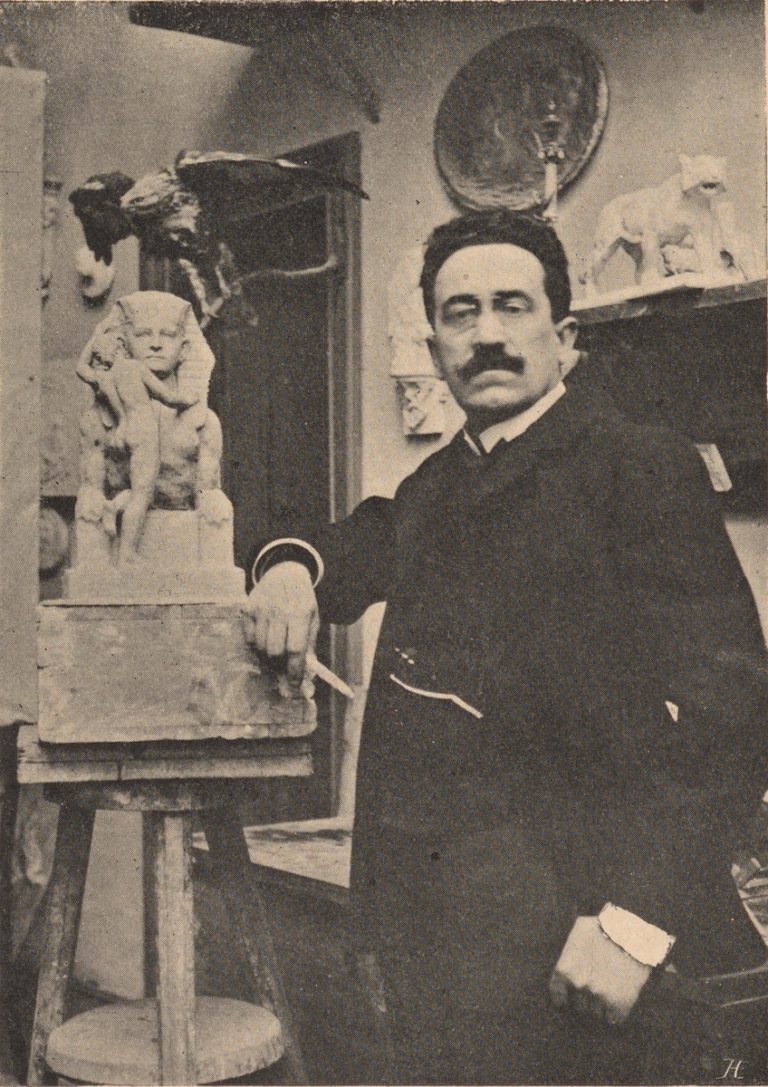

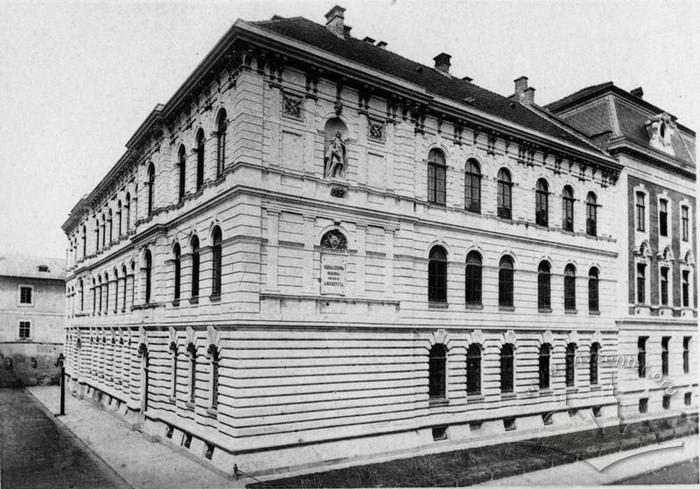

The city was decorated with many symbols not mentioned in the government press but mentioned instead in the patriotic press, which sometimes embellished the reality quite heavily. In particular, the reports pointed out that the walls of the city hall remembered the proclamation of the constitution 100 years before (even though the building was erected in 1827-1835 — ed.). Above the city hall main entrance, a painting by Tadeusz Popiel dedicated to the proclamation of the constitution was placed. Its center depicts the proclamation itself, and on the left are figures of a nobleman, a peasant, a worker, and a Jew working for the good of their homeland and therefore eligible to demand that the rights enshrined in the constitution be respected, as well as a Siberian who demanded freedom of thought and speech; on the other side, to the right of the center, a Polish woman teaches Polish children. On the city hall balcony, there was a bust of the mayor of Warsaw in 1791 (when the constitution was proclaimed) by the carver Antoni Popiel. Above the other entrance to the city hall there was a painting entitled "Mother of God Blessing the Estates," flanked by portraits of Kościuszko and Kiliński. These works were created by Marceli Harasimowicz.

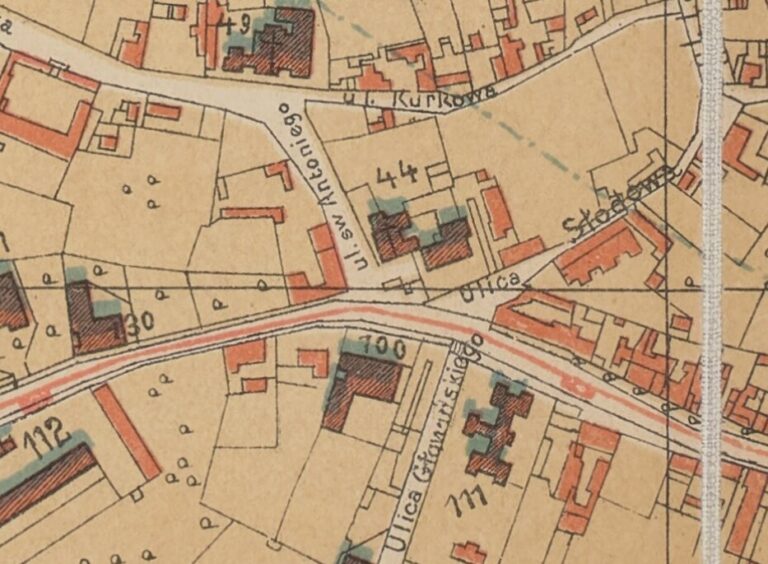

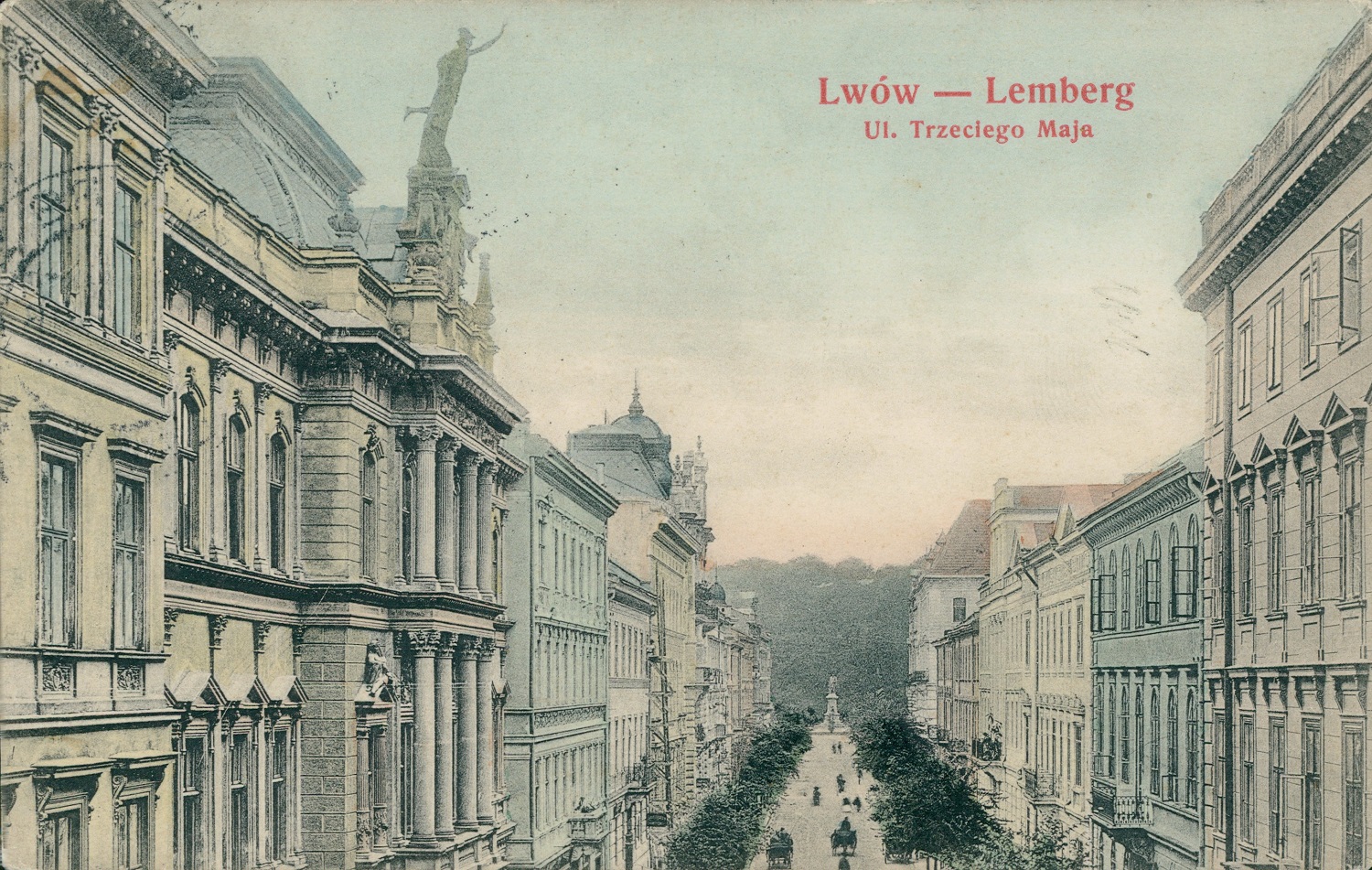

At the end of ul. Trzeciego Maja (which ran alongside the main building of the autonomy — the Sejm — and was named in honor of the Polish constitution after its construction was completed), a triumphal arch was erected at the entrance to the City Park (formerly Jesuit Park). It was designed by Piotr Harasimowicz and made in collaboration with the carver Stanisław Lewandowski. The main element of the arch was a banner painting entitled "The Apotheosis of the Constitution" by Stanisław Kaczor Batowski and Julian Makarewicz. It depicted all the historical figures associated with the constitution, the Mother of God of Częstochowa, and the "estates of Polish society." There were even the coats of arms of Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia with an eagle above them, as well as the coat of arms of Lviv.

Trzeciego Maja Street in Lviv (now Sichovykh Striltsiv Street) leading to City Park. Postcard from the early 20th century.

A banner with an allegorical image of "Polonia" was placed on the building of the Galician Savings Bank; on it, Polonia was receiving gifts from "all estates": a peasant, a peasant woman, a nobleman, a townswoman, and a beggar. The coats of arms of Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia were placed on the building of the Mortgage Bank.

The city's Jewish community also actively participated in the celebrations. Children were excused from school, shop owners decided not to open, festive gatherings were held on the eve of the holiday, and houses were decorated and illuminated. The organizers even printed leaflets with the text of a festive hymn, which was performed in the synagogues of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth on the occasion of the adoption of the constitution, to distribute them in the synagogues of Lviv on the 3rd of May.

Celebrations in 1891

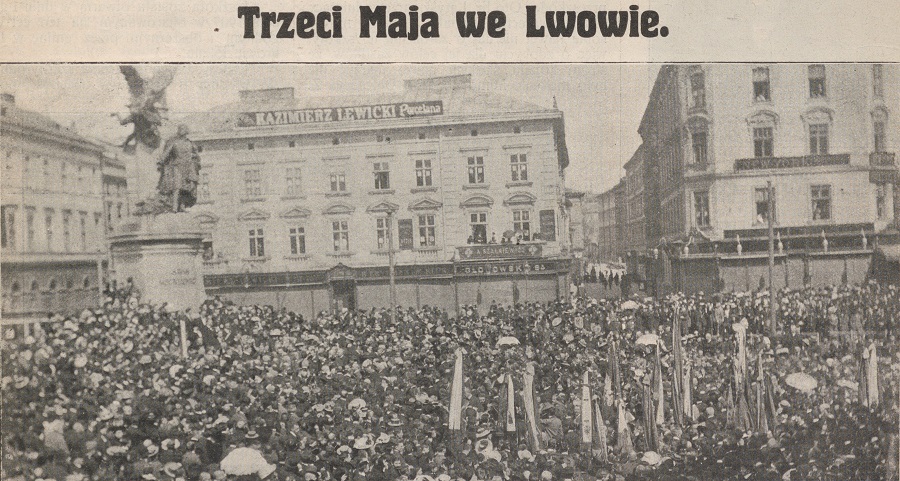

The course of the 1891 celebration resembles the traditional celebrations that took place in Lviv on the occasion of imperial anniversaries. The patriotic press described "thousands of flags in national colors" and wrote about a festive cannon salute at 5:30 a.m. However, the latter was not mentioned in the government newspaper, and in general, according to the official description, the celebration was rather modest.

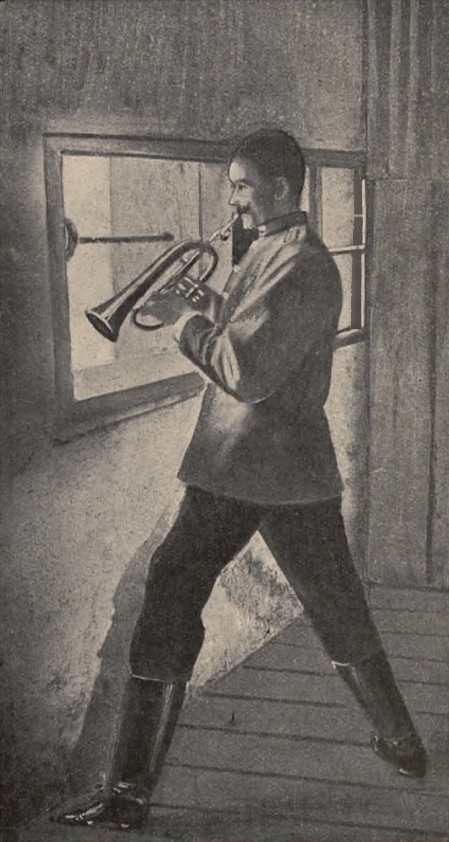

At 6:00 a.m., the Harmonia musicians dressed in Polish hussar uniform, played the "reveille" on the city hall tower. Then they marched through the city streets, playing Polish melodies. Actually, this was a reproduction of standard Austrian imperial rituals: a military "reveille" and a military band parade.

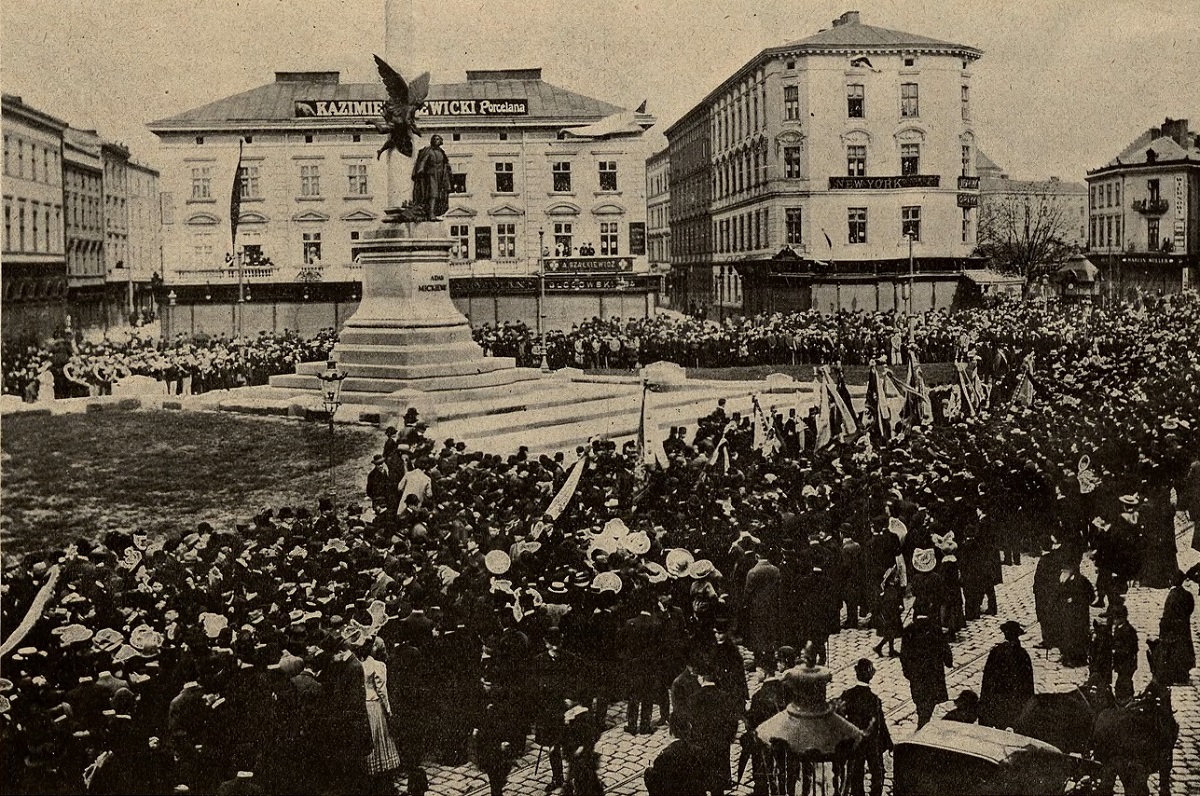

In the morning, young people erected a "national standard" on the Lublin Union Mound to the sounds of "anthems" (which were not specified). After that, they went to the Rynok Square, where representatives of the autonomous authorities, the city council, societies, and corporations had gathered. Actually, this was the usual composition for any imperial anniversary, with the exception of government officials.

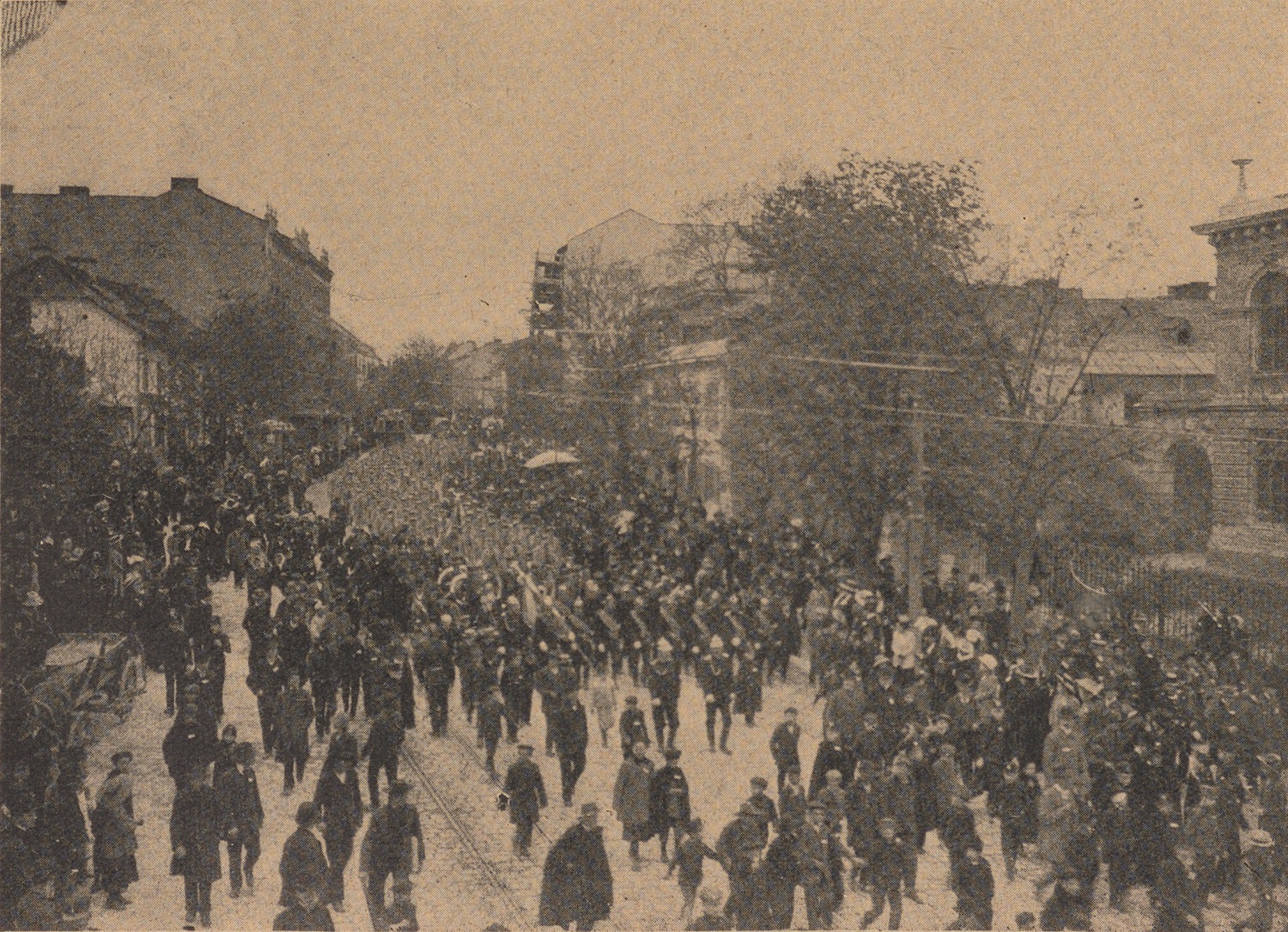

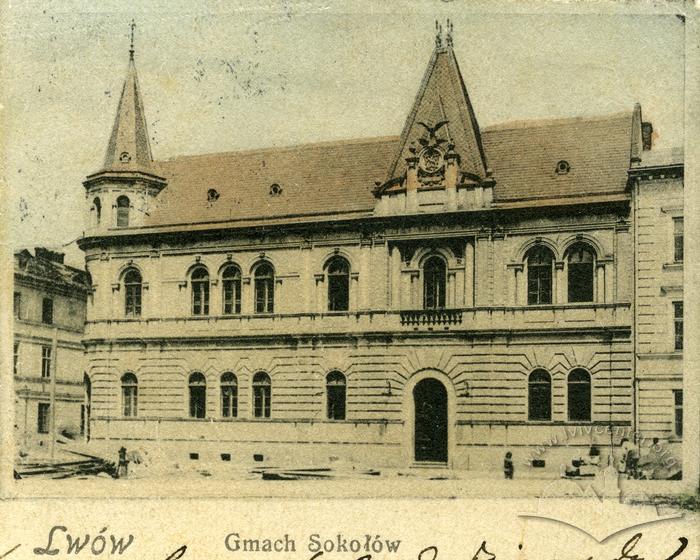

At 9:00 a.m., the hejnał was played from the city hall tower — a borrowing from Krakow this time. According to newspaper reports, the melody, which was "unknown in Lviv," made a good impression on people. Then, accompanied by the music of the Harmonia band, people walked around the city hall and entered the Latin Cathedral. The column of several thousand people looked like this: the leaders of the civil guard in "national costumes," the "volunteer guard" division, the orchestra, peasants, members of the Skała and Gwiazda societies with banners, schoolchildren, students of the University, Polytechnic, the Dubliany institution, the foresters' school, and future veterinarians. Then about 2,000 workers (although this is probably an exaggeration due to the political preferences of the Kurjer Lwowski newspaper) with a red banner bearing the inscription "Workers' Party." Their participation was intended to dispel all the calumnies of the "Pharisees" that workers did not feel Polish. Next came the members of the Sokół society with a standard and a banner reading "A strong body means a strong spirit." Then there were participants in the 1831 and 1863 uprisings; the members of the Women's Reading Room (pol. Czytelnia kobiet), in national costumes or with national symbols; came the members of the Sejm, the State Council, and the Provincial Department (in national costumes as well). The City Council, headed by President Edmund Mochnacki, was present in full force, also mostly in national costumes. Next came members of the Rifle Society, Jewish organizations, the Chamber of Commerce, lawyers (also in national costumes), notaries, guests from Krakow, financiers, actors, writers, the Historical Society, the Mickiewicz Society, "and all other Lviv societies," as well as the fire brigade.

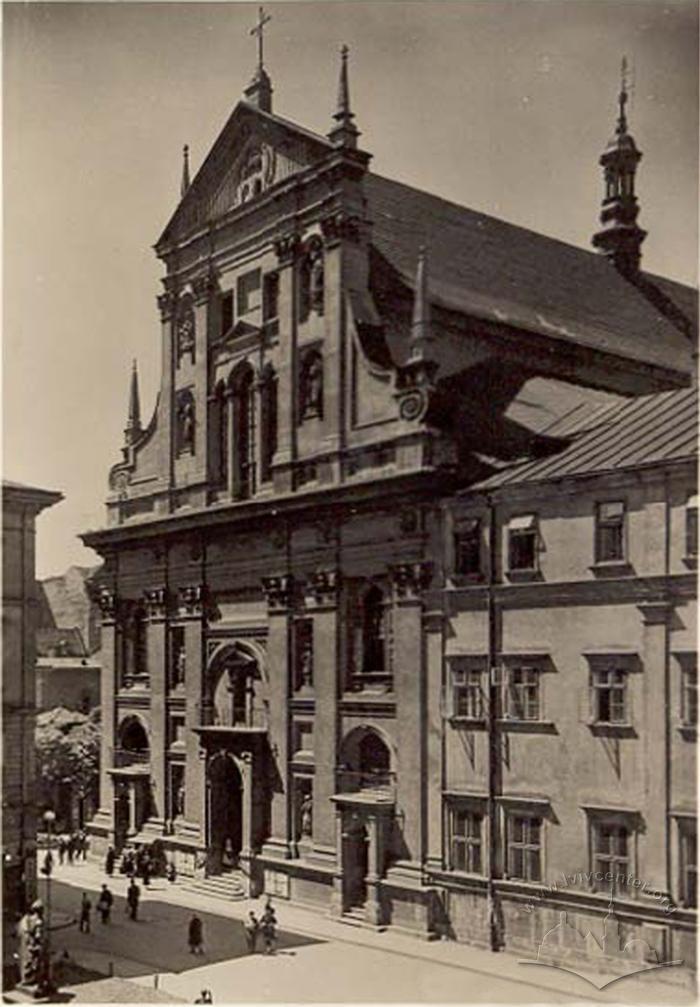

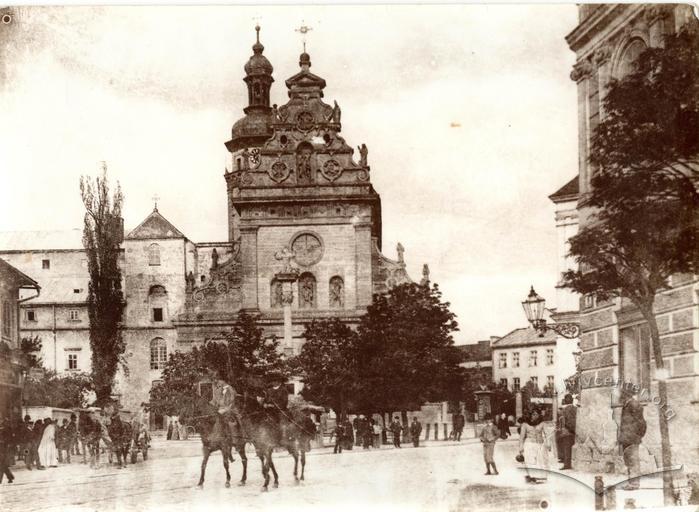

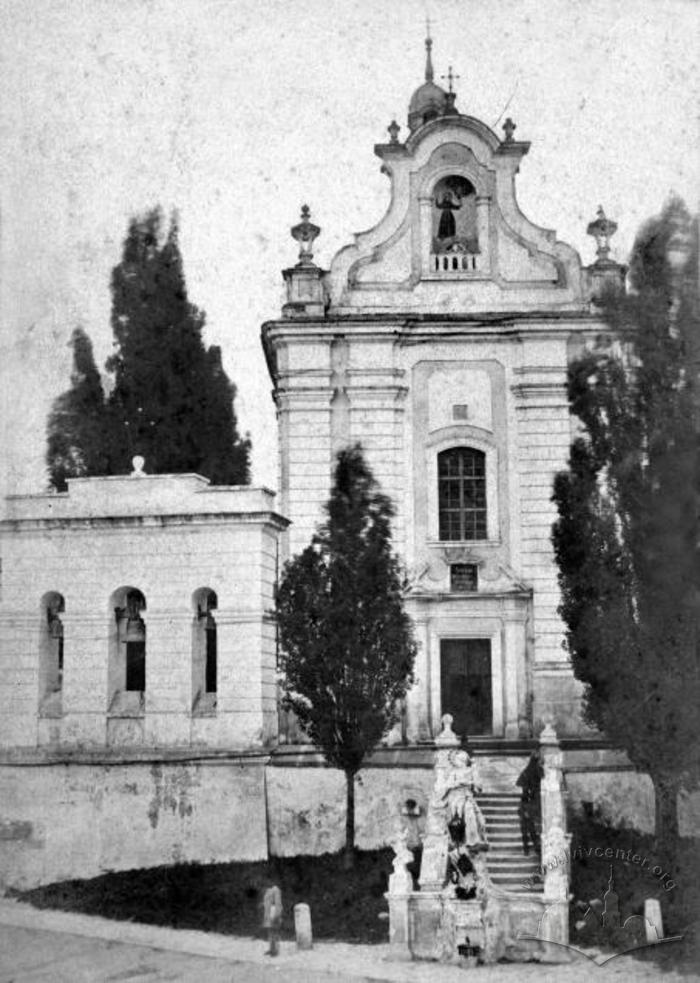

At 10:00 a.m., a solemn service began in the Latin Cathedral, where the choir of the Lutnia Society sang. The Sejm Marshal Eustachy Sanguszko was also present. At the same time, services were held in the Bernardine Church, the Armenian Cathedral, the churches of St. Nicholas, the Dominican, Franciscan and Jesuit churches, as well as in the churches of Mary Magdalene and St. Anthony. Choirs from various organizations also sang at these services; for example, pupils from the school for the blind sang in the church of St. Anthony. A festive service was also held in the synagogue in the Zhovkivske suburb, attended by members of societies, Jewish members of the City Council, and representatives of the Chamber of Commerce. At the end of the service, all those present sang "Boże coś Polskę".

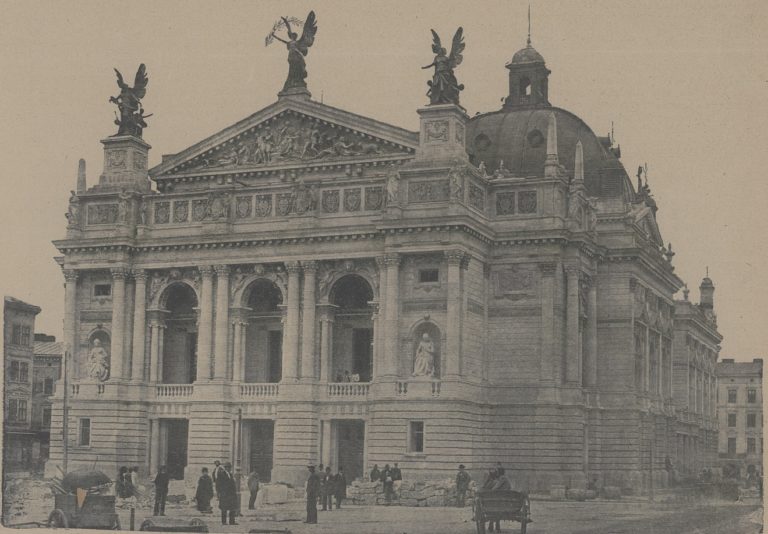

After the service, at 1 p.m., people took to ul. Trzeciego Maja (now vul. Sichovykh Striltsiv), which was decorated with garlands and flags on flagpoles, the houses draped with carpets and banners. Not each one, however: the modest decorations on the buildings of the National Casino and the Sejm "were a disappointment." The procession was greeted in front of the triumphal arch by the Harmonia choir and schoolchildren waving white and red flags as the procession passed through the triumphal arch.

Solemn meetings were held in four halls in the afternoon. The city hall was attended by Count Włodzimierz Dzieduszycki, the city president Edmund Mochnacki, the vice president Zdzisław Marchwicki, and the Provincial Department member Józef Wierzyński. Similar meetings, with lectures, poetry recitals, and patriotic songs, were held in the city casino, in the buildings of the Sokół and Skała societies. The lectures dealt with the political situation, such as the role of Catholicism as the basis for the Polish identity formation, or the need for mutual understanding with Ukrainians. Peasants who came to the festival from villages near Lviv were accommodated in the Skała society hall.

In the afternoon, at 4 p.m., folk entertainment for young people took place at the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) hill, with musical accompaniment provided by the Harmonia band. The participants in the event, accompanied by orchestras, came to the Lublin Union Mound and embedded a commemorative plaque in the remains of the castle wall. Here, the villagers sang folk songs and politicians gave speeches. The official part of the event ended with the performance of the "Dąbrowski March," after which the "folk festivities" began. At the same time, the Skarbek Theater was showing the play "Kościuszko near Racławice."

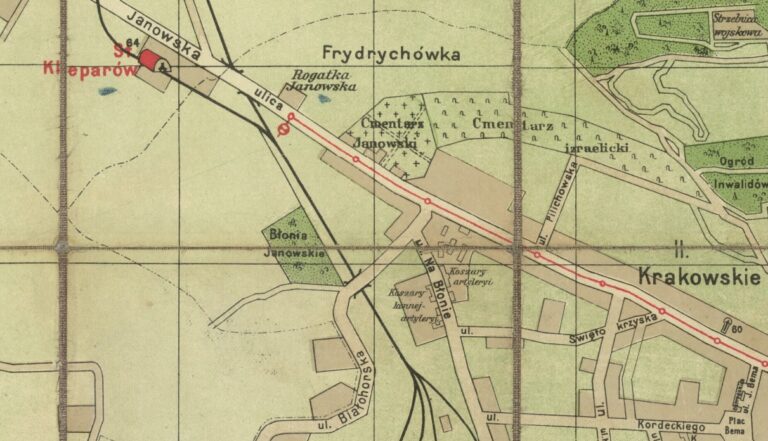

The evening illumination of the city, which began at 8:00 p.m., consisted of large bonfires lit on the Mound, in the Kiliński Park, and on the Janowski hills, gas and electric lamps, Chinese lanterns on buildings, as well as candles in the windows of homes and shops. However, not everyone, as the patriotic press reported, treated the holiday "responsibly": while the Dominican monastery was brightly lit, the Jesuit church was not. The administrative building of the Karl Ludwig railway was illuminated, while the State Railway Administration on ul. Trzeciego Maja was not.

It was important that the police were "not visible" on the streets on that day, with order being maintained by the civil guard. In the evening, the wives of firefighters patrolled the streets (and even extinguished a curtain that caught fire). At midnight, the head of the civil guard reported to the police director that everything was in order and that no incidents had occurred during the day.

In the future, although the celebration of the 3rd of May was not as massive as on the 100th anniversary, it nevertheless became traditional, with at least church services, fundraising for charitable purposes, and meetings in organizations. At the same time, the role of paramilitary organizations grew, involving peasants even more actively. Accordingly, the focus of the events and their geography also shifted.

Celebrations in 1911

On the 120th anniversary of the constitution (1911), houses were traditionally decorated with stickers on the windows. Five flags "in Polish colors" (now no longer "national") were placed on the city hall tower. On the eve of the celebration (again, an analogy with the honoring of the emperor comes to mind), three orchestras marched through the streets with lanterns.

On May 2, a festive evening event was held at the city hall, attended by clergy and representatives of the City Council. They talked about the equality of social classes, modernization, and the role of the peasantry and bourgeoisie in politics.

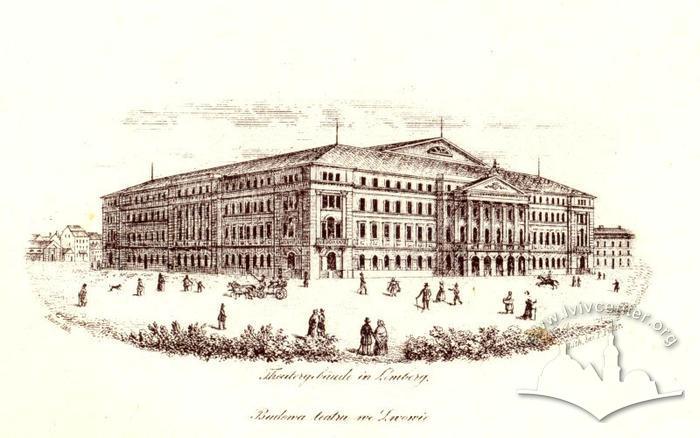

The traditional program included a gathering at the Vysoky Zamok hill at 5 a.m. and a solemn march to the Rynok Square. At 7:00 a.m., the Gwiazda members and their families "traditionally" sang "Boże coś Polskę," "Jeszcze Polska nie zgineła," and "Witaj majowa jutrzenko" on the city hall tower. At 8:00 a.m., the hejnał was played from four corners. The solemn service in the Latin Cathedral, which was decorated with red and white electric lights for the occasion, was attended by the provincial marshal, the city council members, the university administration, as well as the Sejm and the State Council members. Various societies, guilds, and participants in the 1863 uprising were also present. In the evening, a meeting was held in the Academic Reading Room and a special performance was staged at the city theater.

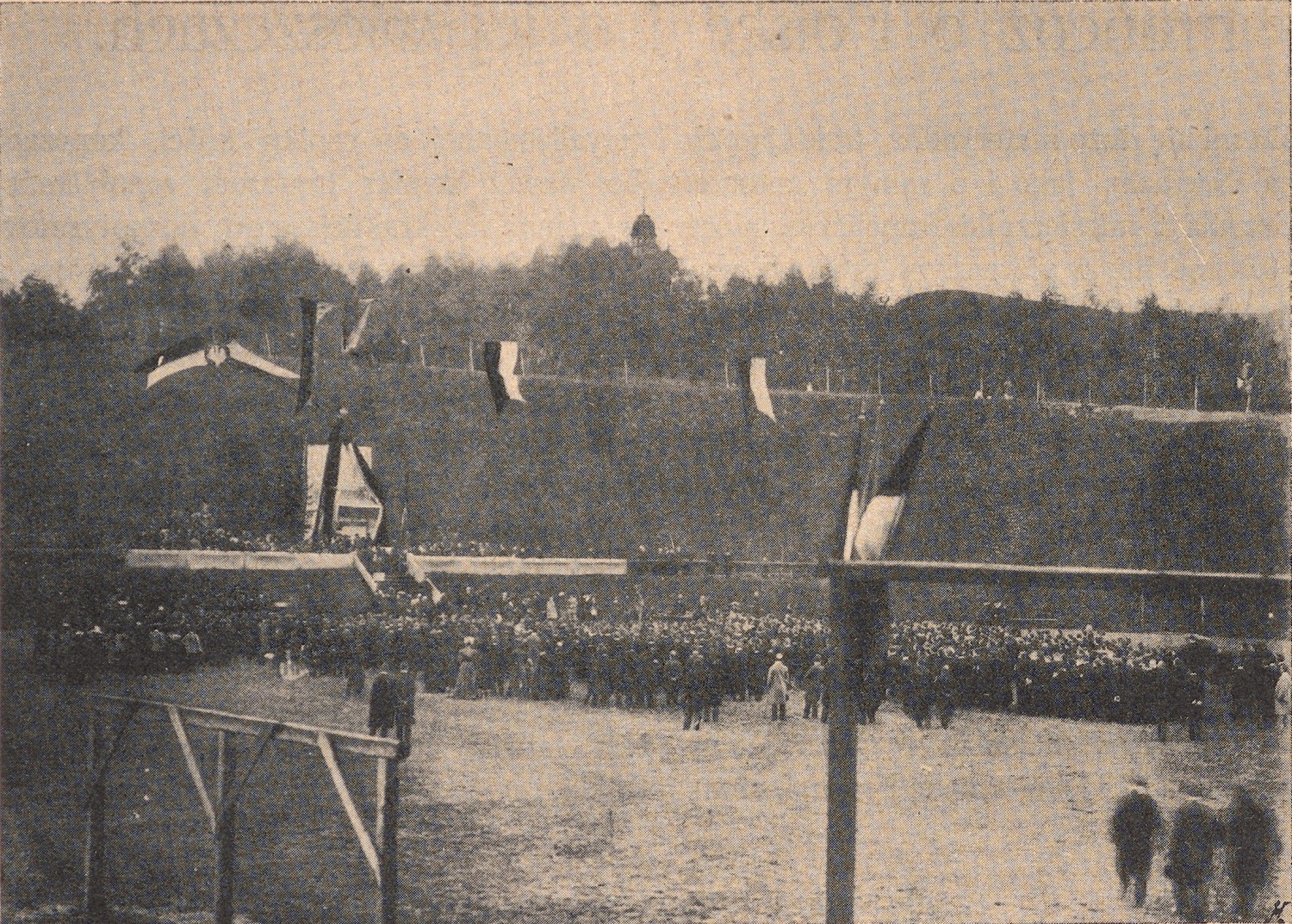

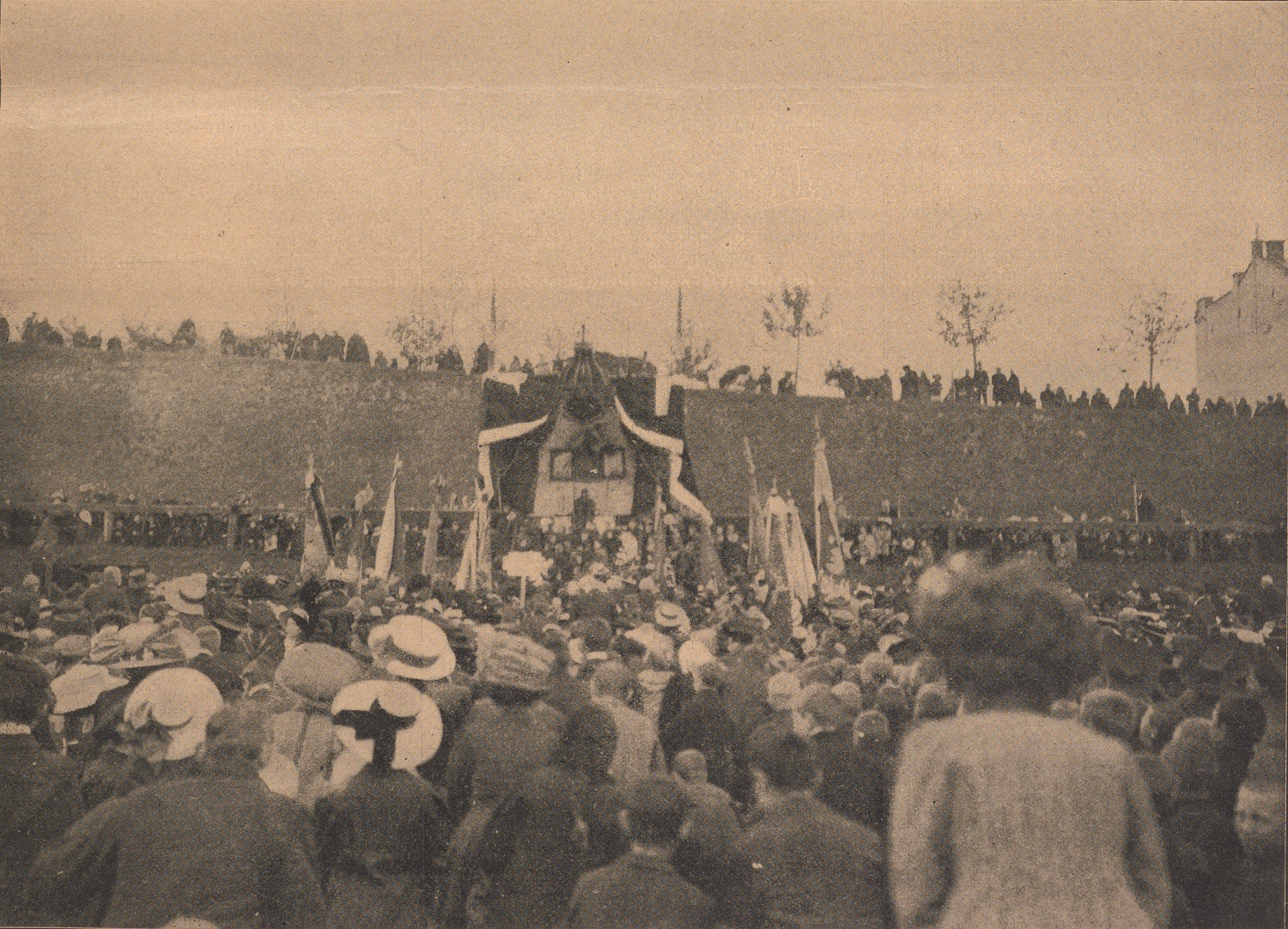

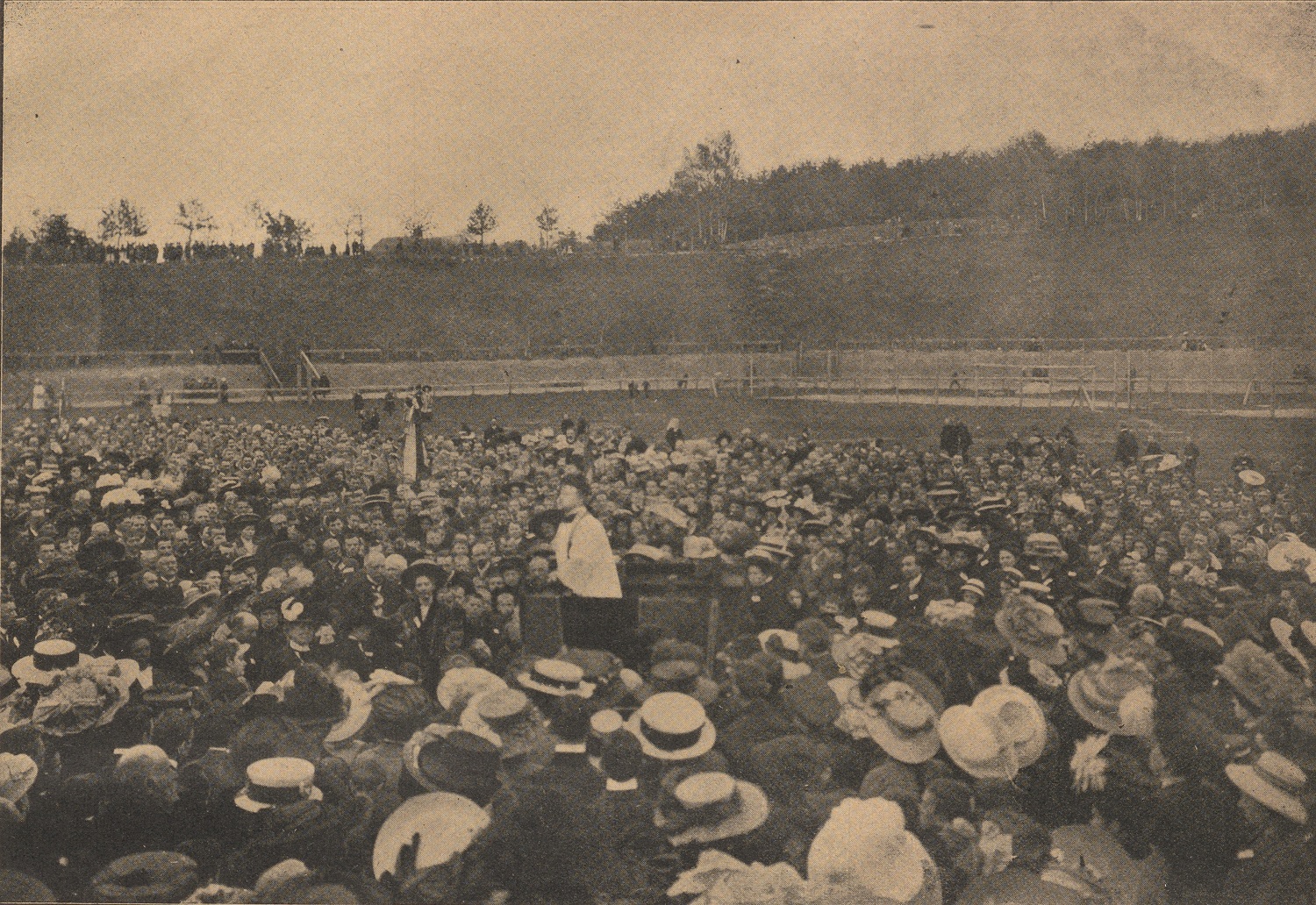

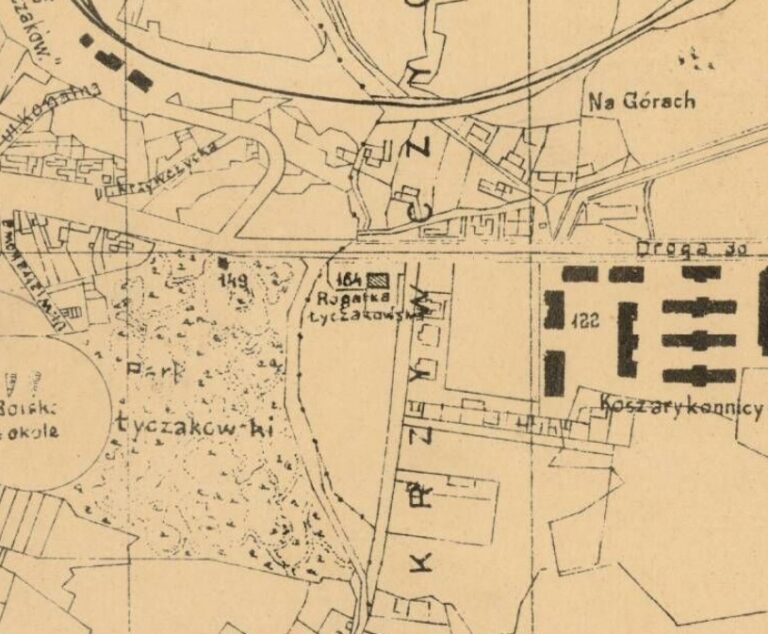

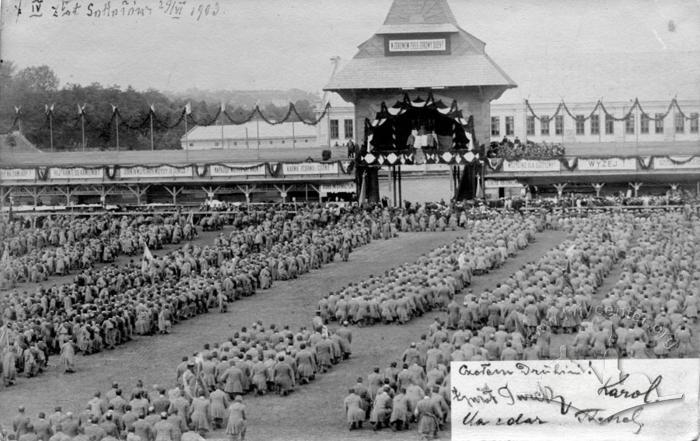

Peasants and paramilitary organizations began to play an increasingly important role at this time. For example, the Mickiewicz School became a gathering place for peasants from the villages near Lviv, who came to the festival with their children, dressed in folk costumes and accompanied by musical bands. At 11:15 a.m., a field mass was held at the Sokół Stadium (similar to what was done for the military garrison during the emperor's anniversaries). Representatives of the City Council, societies, participants in the uprising, and several thousand spectators were present.

On Sunday, May 7, a tourist hike to the Devil's Rocks was organized to mark the Constitution Day.

In 1914, in addition to the solemn gatherings, orchestras in the streets, a field mass at the Sokół Stadium, illuminations, and other customary events, a field kitchen for peasants in the City Park, a procession to the Adam Mickiewicz monument, and training for Sokół organizations on a vacant lot behind the Lychakivska "turnpike" were added. Among the decorations on the houses, white eagles now predominated.

Interpretation

As we can see, the celebration of the 3rd of May in Lviv began in the spirit of "positive work" on the basis of self-government and de facto national autonomy. At the initial stage, the organizers copied the imperial rituals typical of state holidays.

However, over time, as nationalism spread, specific features began to emerge. The idea of a "new society" in which not only aristocrats but also townspeople and peasants, as well as Jews as part of the political nation, were politically active, influenced the ritual of celebration and its geography. For example, a huge role was assigned to the city hall.

The very fact of holding celebrations, preparing the city, and ensuring law and order by the "civil guard" was supposed to confirm the maturity of Polish society. In fact, a belief was forming that "society" could do everything that the state authorities could do. Hence, the civil guard instead of the police, orchestras instead of military bands, the Sokół instead of the army, illuminations, gatherings, and so on. Ultimately, it was a triumphal arch through which the "people" passed, not the emperor and his entourage.