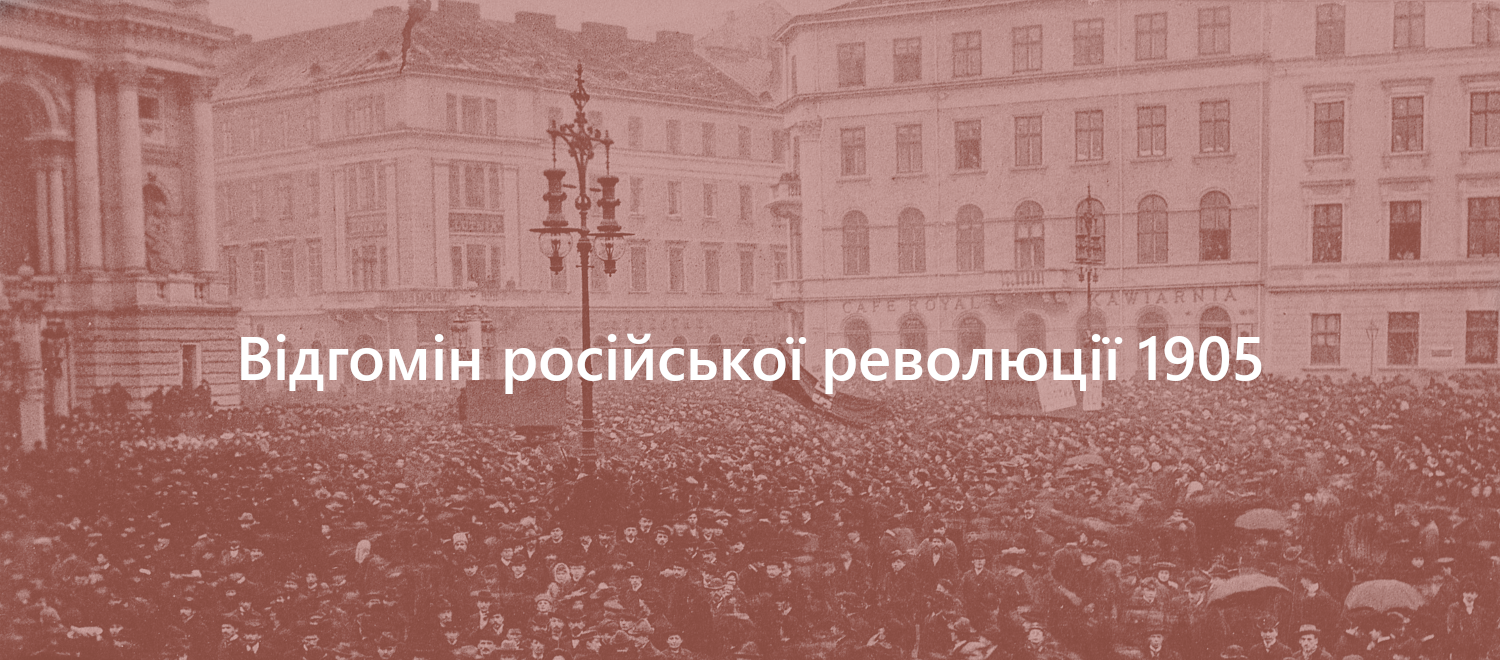

Though in the early 20th century Lviv was not an industrial center with a large number of workers, the Russian Revolution had a significant impact on life there. First of all, this was manifested in actions of solidarity with the workers of Russia organized by local politicians and activists during each aggravation of the situation in the Russian part of Poland (Kingdom of Poland). Due to the liberal Austrian legislation, the Poles of Galicia could hold demonstrations much more freely, including in support of the Poles of the Russian Empire.

The revolution in Russia began with the "Bloody Sunday", when a peaceful demonstration in St. Petersburg was shot in January 1905. After that, a wave of protests swept through the cities of the empire. In the Kingdom of Poland, where riots had been taking place since 1904, the "Bloody Sunday" became the catalyst for a strike in which 400,000 workers took part. About 100 people died during protests in Warsaw alone and in January alone. These events had a significant impact on Polish political activists in Lviv. Thus, in February 1905, they organized an action "against Russian barbarism in Poland", that is, against the repression of demonstrators there. Another significant event was the tsar’s "gift" of the constitution in October 1905, which, however, did not affect the Kingdom, which was under a state of emergency. In Lviv, this caused unrest among nationalist youth and intensified the struggle of social democrats to change the Austrian electoral legislation.

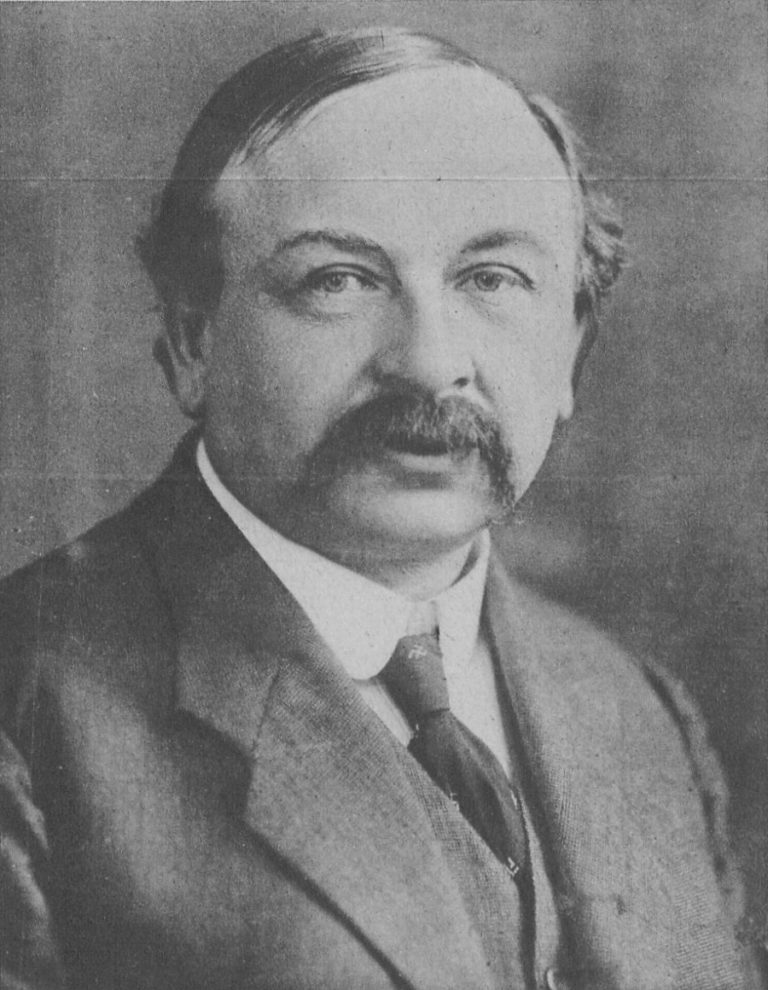

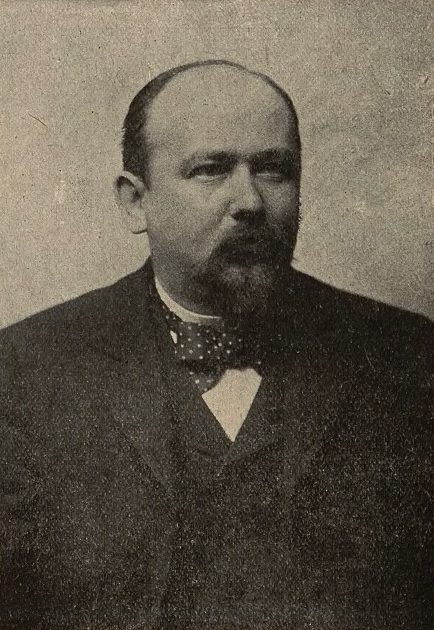

"Bloody Sunday" on January 22, 1905, in St. Petersburg. Picture by Wojciech Kossak. Source: Sopocki dom aukcyjny

The events of 1905 in Russia effectively shaped the political agenda for Polish politicians in Lviv, and the division between them reflected a similar division in the Kingdom. Two camps were the most active: national democrats (pol. endecja), who were skeptical of the protests, condemned socialism and the cooperation of Polish political forces with Jewish ones, and social democrats (Polish Social Democratic Party of Galicia and Silesia, PPSD), who stood in solidarity with the protesters in the Kingdom.

When there was a violent, sometimes bloody confrontation between the socialist protesters and the nationalists in Warsaw, it resulted in periodic attacks on the editorial office of the national democratic periodical Słowo Polskie in Lviv. The latter regularly condemned the "socialist terror of the left wing", the left wing supporters responding by breaking windows of newspaper kiosks.

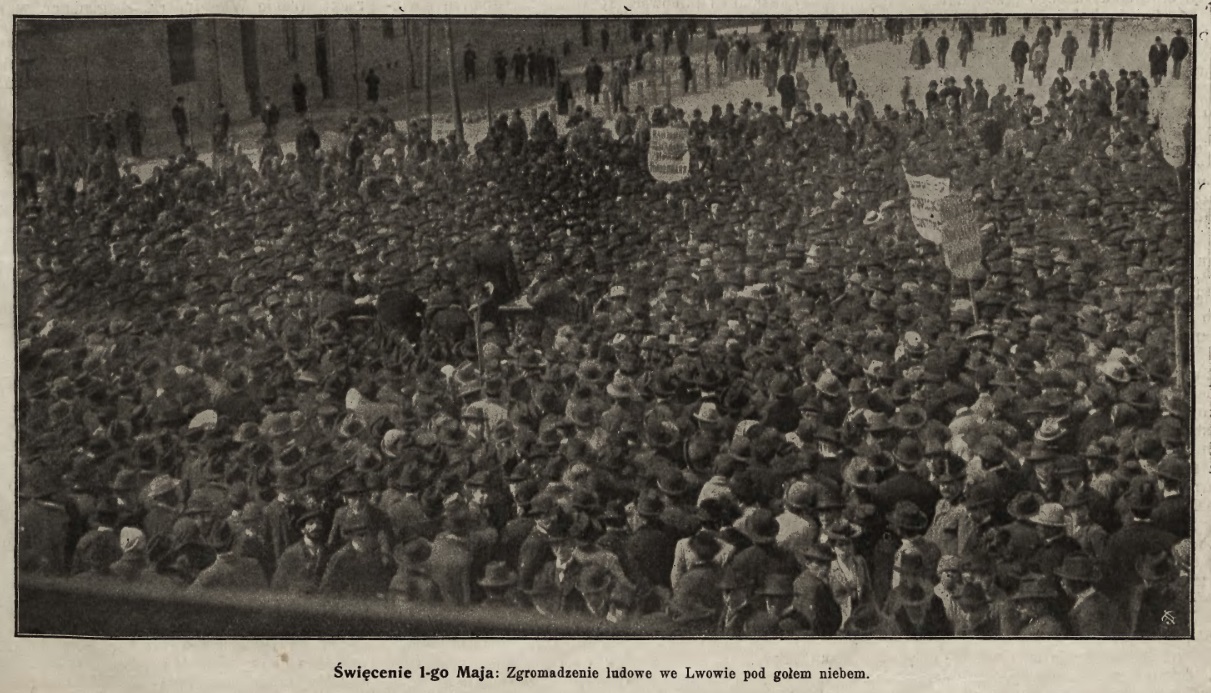

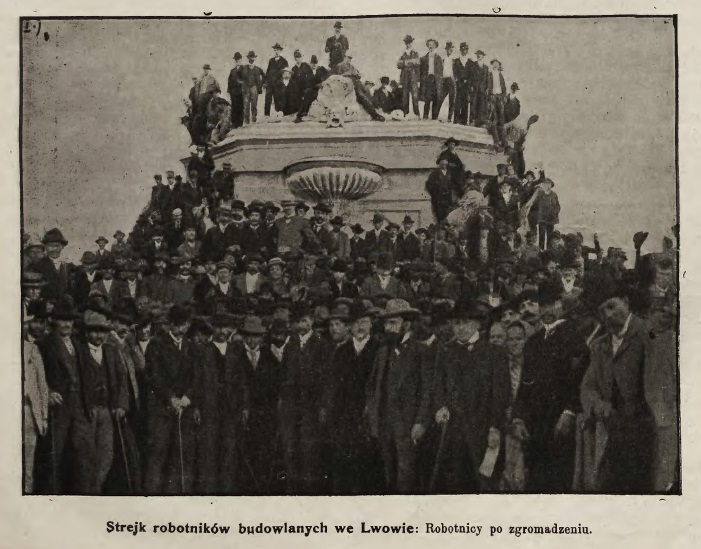

Over time, although Lviv remained an important center primarily of the "all-Polish national revival", this unofficial status also came in handy for socialist politicians. After all, in 1905 Lviv could be considered an important center, including that of the labour movement, a place of meetings, assemblies and demonstrations. The workers' strikes in Lviv in May and July, even though they were relatively conflict-free, allowed the social democrats to constantly remind of themselves. Sometimes, as in the case of the rally of July 1905, they even managed to seize the initiative in the patriotic domain altogether.

After the proclamation of the constitutional order in Russia in October 1905, the social democrats came to the fore again: in November 1905 they were able to organize massive rallies in support of universal suffrage in Austria-Hungary. It was only traditional events dedicated to the November Uprising that helped the national democrats come back to the public space. Moreover, under the influence of the events in the Russian Empire, these actions were also not without conflicts and confrontation with the authorities. Furthermore, in November 1905, there was a bloody crackdown on a Ukrainian demonstration protesting against the celebration of the anniversary of the defense of Lviv from Bohdan Khmelnytsky’s army.

There were no confrontations of this kind in the Ukrainian camp, but the situation was also far from idyllic there. Populists and supporters of the Christian social movement had been skeptical of the ideas of international solidarity of workers even before. Like the Polish national democrats, they often appealed to the anti-Semitism of their supporters, calling the demonstrations of the left wing "gatherings of socialists and Jews." Besides, they considered the slogan "proletarians of all countries, unite" to be manipulative. Using it, the Polish social democrats, they claimed, masked their chauvinism and turned the Ukrainian left movement into an appendage to the Polish one. When the Polish leftists, in the opinion of populists, switched to distinctly nationalist positions in 1905, Ukrainian left-wing politicians (members of the PPSD) supported them, whereas the Jewish social democrats retained more "national dignity" by acting separately.

The PPSD was actually the most visible political force during the events of 1905 in Lviv. This organization was the successor of the former Social Democratic Party of Galicia. It was renamed "Polish" as early as 1897, but it continued to claim to represent the workers of all nationalities living in the province. Among its main speakers were Ukrainians Semen Vityk and Mykola Hankevych, who spoke in both Ukrainian and Polish, as well as Herman Diamand, who represented Jewish workers.

After the "renaming" of the Galician party, the Ukrainians founded their own Social Democratic Party (USDP), but its leaders Vityk and Hankevych remained in the leading ranks of the PPSD and held joint actions. Instead, part of the Jewish social democrats announced the formation of the Jewish Social Democratic Party (ŻPSD) on May 1, 1905. It did not confront the PPSD, but held separate actions, mostly in "its own" areas of the city and mainly for those who did not support the policy of assimilation of Jews. The actions of Jewish activists in 1905 had their own specificity and were dedicated not only to solidarity with the workers in the Kingdom of Poland but also to a national tragedy: the pogroms of 1905 in the entire Russian Empire.

Consequently, in many cases the leftists acted in Lviv as two separate groups: "Christian" (Polish-Ukrainian) and "Jewish" social democrats. However, they often claimed to coordinate their efforts to protect workers' rights.

*

Polish patriotic politicians who controlled the City Council (they can also be called the Strzelnica group) found themselves in a very delicate situation. The Lviv City Council always responded to the oppression of the Poles in the Kingdom of Poland or in German-controlled territories. The main protagonists of the labour unrest were, however, socialists. Moreover, in order to beat them, it was necessary to face the rejection of the central government. For example, a declaration of solidarity with the Poles who fought against the tsarist regime was adopted in the City Hall, on the proposal of the social democrat Józef Hudec and to the cheers of those present. The position of the president of the city, Michał Michalski, on this issue caused the displeasure of Andrzej Potocki, the governor of Galicia.

The situation was not easy, since Austria-Hungary officially considered Russia a friendly country, and, to put it mildly, did not accept the very idea of workers' demonstrations. Therefore, the meeting of the social democrats on January 30 was banned with the wording "in view of the position of a friendly state."

*

It can be said that the events of 1905 were one of the main outbursts of left-wing activity in the city. This was probably achieved due to the fact that it was possible to combine a social agenda (the struggle for workers' rights) and national or class solidarity (with the striking Polish workers or the Jewish victims of pogroms in Russia). However, it is difficult to say which kind of motivation, labour or national, inspired the participants of the actions more.

The events of 1905 were also characterized by another trend. From time to time, the organizers lost control over the situation and there was a violent confrontation. These were clashes between striking workers and strikebreakers, the use of force by the police during the dispersal of demonstrators, the devastation of newspaper kiosks and editorial offices. In all these cases, politicians tried to both justify the actions of their supporters and distance themselves from them.