In Lviv, the Ukrainians (mainly Greek Catholics) and the Poles (mainly Roman Catholics) used different — Julian and Gregorian — calendars. Consequently, Christian holidays fell on different days for them. Each group had not only its own dates and ways of celebrating the same holidays but also different priorities in the celebrations; so, the same holiday could be virtually a mass manifestation for some city residents and an almost unnoticeable event for others. In addition, each group tried to create new, purely "their own" religious cults with a national flavour. All this led to the formation of separate "national" church calendars, each particular to a specific national-denominational community.

* * *

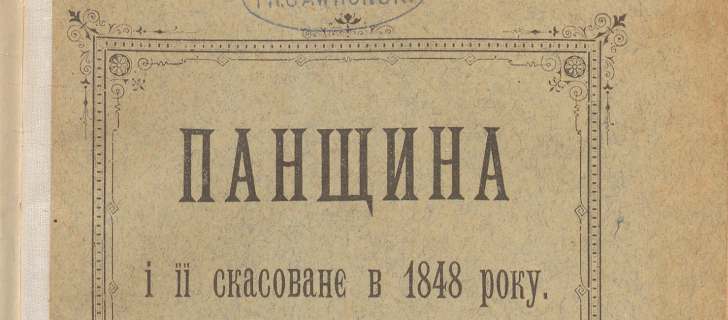

For instance, "Ruthenian" choral singing on Good Friday, church services on the anniversary of "Freedom Day", i.e. the anniversary of the abolition of corvee labour, solemn services on the day of the Protection of the Mother of God associated with the Cossack cult were quite famous. An example of a successful combination of the national and the ecclesiastical was the cult of Markiyan Shashkevych, who after his death became the personification of both the "good priest" and the "national awakener." Instead, the anniversaries of the 1596 church Union of Brest never became "popular" in the conditions of the growth of nationalism and increasingly tough confrontation with the Poles.

The tradition of visiting cemeteries also differed from the "Polish" one as the Ukrainians visited graves on the Green Holidays (Pentecost) while the Poles did it on November 1.

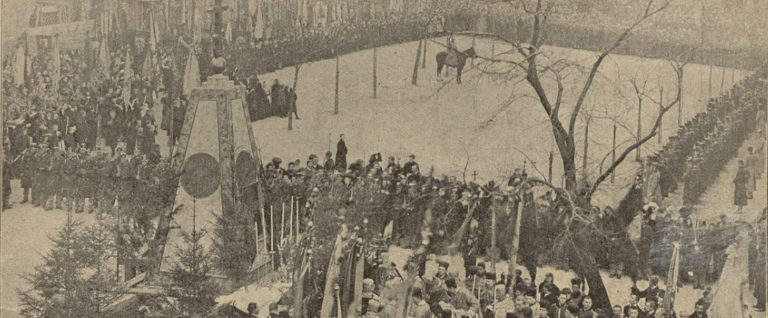

For the Ukrainians in Lviv, the most massive annual celebration was the Epiphany celebration on January 19, with the consecration of water in one of the fountains on the Rynok Square, with the participation of the city and provincial authorities, with the involvement of the military, which did not happen often in the case of "Ruthenian" events.

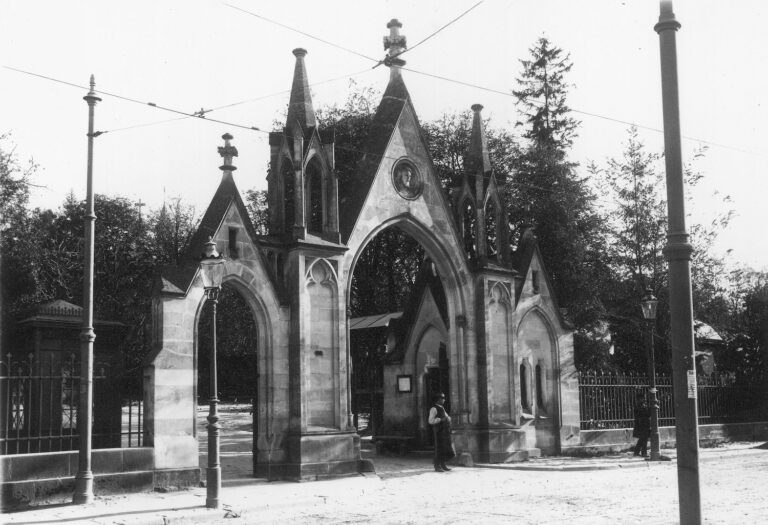

For the Poles, the most massive religious event was the feast of Corpus Christi, which coincided with the re-election of the "rifleman king." On those days, parades, fireworks and mass celebrations were held in the city, complementing solemn processions with Holy Gifts (Eucharist) around Roman Catholic churches.

- Йордан у Львові / The Epiphany in Lviv

- Свято Божого Тіла / the feast of Corpus Christi

It is worth noting that the popularity of Latin rites was one of the reasons for the conversion of Greek Catholics to Roman Catholicism. Therefore, the Greek Catholic clergy, in order to prevent "polonization" (that is, the loss of parishioners), took care of the "cultural distance" between the Uniates and the "Latins." At the same time, they also tried to borrow some popular ritual elements that were considered "Polish." For example, there were celebrations for Corpus Christi, which followed similar Roman Catholic rituals, but according to the Julian calendar.

In Habsburg Lviv, naturally, the best opportunities to manifest their "national religiosity" belonged to the Poles. One such opportunity was the "meetings with the consecrated [food]" (pol. zebrania przy "święconem"), which were traditional gatherings in associations and organizations that took place after Easter. Various issues, including political ones, were discussed there, even the prospects of equality of all social classes. These, however, were not quite usual political or religious events: members of the associations like the Sokół and the Gwiazda, the January Uprising Veterans' Association, and the Rifle Association used to come with their families, turning the "meeting with the consecrated [food]" into something like a political, religious, charitable and family event at the same time. Thus, meetings in the City Hall, described as an example of "old Polish hospitality", were intended to raise funds for orphanages. These gatherings, unlike New Year's carnivals, focused on family traditions rather than entertainment.

The idea of the "All Souls Day" on November 1 was also transformed under the influence of modern ideologies. The traditional lamps on the graves remained, but now it was not so much about visiting the graves of relatives as about honouring "outstanding thinkers and fighters for the freedom of the nation." Patriotic youth decorated the crosses on the graves of the January Uprising participants and the cross erected in memory of the victims among the Uniates in Podlasie. Visits to the graves turned into rallies where patriotic songs were sung and speeches were made over the insurgents’ graves. Socialist youth used to come to the grave of the author of the song "Red Flag", Bolesław Czerwieński. An important place on November 1 was the Execution Hill and the monument to insurgents Wiśniowski and Kapuściński.

In addition to the popularization or adaptation of existing dates, in the early 20th century, when Józef Bilczewski was the Roman Catholic archbishop of Lviv, the creation of new cults and holidays can be observed.

In particular, the archbishop actively promoted the cult of Queen Jadwiga; in November 1905 he organized the "First Marian Congress in Polish lands." In the same year, 1905, with the assistance of the City Council, Roman Catholics began to pompously celebrate the anniversary of the "vows of Jan Casimir", i.e. the symbolic "handover" of the Polish lands by the king to the protection of the Mother of God, which took place in the Lviv Cathedral in 1656. Celebrations directly related to the topic of foreign conquest provided a wide field for reflection. Chronologically, this date was very close to May 3, the National Constitution Day, so the celebrations did not go beyond a mass and a patriotic sermon after it. This holiday became annual, along with other spring and summer celebrations: the Third of May, Easter, Corpus Christi.

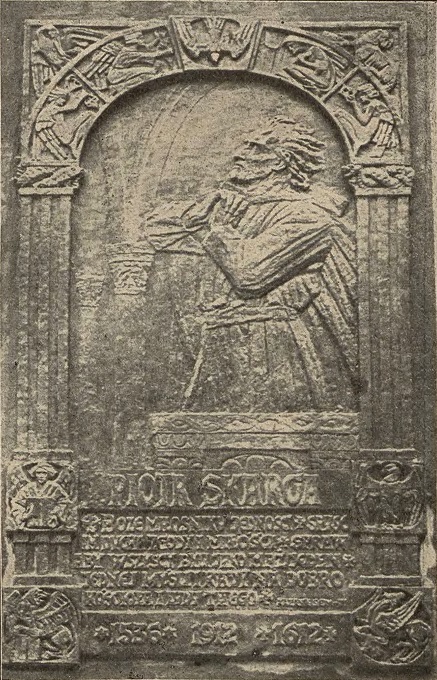

In 1912, under the auspices of Archbishop Bilczewski, the anniversary of Peter Skarga, a leading Polish Jesuit thinker of the 16th century, was celebrated. The main events took place in Lviv: a festive service was held in the Latin Cathedral and a solemn assembly was organized in the Dominican Cathedral, a memorial plaque was opened.

From the Ukrainian point of view, these celebrations were another example of "inventing anniversaries", as well as patriotic memorial "tours" dedicated to the January Uprising. Moreover, the Ukrainian press did not miss the opportunity to emphasize that Polish patriotism or religiosity in Lviv was based on administrative resources.

For example, the Dilo newspaper reported that on the feast of Corpus Christi according to the "Ruthenian rite" in 1909 in Lviv, there were ten times less military personnel than on the "Latin rite" Corpus Christi, while the representation of the secular authorities was minimal. In addition, the military band that accompanied the Ruthenian holiday played "Polish marches." Moreover, when the religious procession went through the Rynok Square, a "Polish provocation" took place: "a festive group came out with music" from the City Hall and found itself amidst the Ruthenian procession. To the chants of "Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła" they elbowed and hustled the Ukrainians carrying church banners. A conflict was brewing, but the Greek-Catholic clergy urged the Ukrainians to calm down. Probably, it was somehow connected with parallel events honouring Berek Joselewicz, which were taking place in Lviv at that time on the occasion of the 115th anniversary of Tadeusz Kościuszko’s victory near Racławice.

The Armenian clergy essentially acted as Roman Catholics, joining the Polish national project. Therefore, there is no need to talk about any specific Armenian religious and national celebrations. The Jewish community was distinctly national, and therefore all their religious holidays had a national specificity. The situation with the Orthodox church was also curious, since, although not considered purely Ukrainian, it was this church that for a certain time in the mid-19th century was the only place for honouring Taras Shevchenko, until this function was taken over by secular organizations.

* * *

Thus, there were many religious rituals with a clearly expressed national character. As the popularity of nationalism grew, they were becoming even more numerous. Along with massive pompous celebrations, there were smaller but no less "popular" religious holidays, which formed specific "calendars" for the national communities of Lviv.