In July 1905, construction workers went on strike in Lviv. In contrast to the strikes that took place in May, in July everything was developing in a much more dramatic and organized way. On the one hand, social democrats constantly kept the strikers "on their toes", talking about solidarity with the Warsaw strikers or other Lviv workers, organizing assemblies and marches. On the other hand, they tried to prevent conflict situations.

Since the strike itself lasted for about three weeks, during it workers, nationalists, socialists, the police, as well as the City Council and the governor’s office had enough time to show their worth.

The beginning of the strike, workers' demands, pogroms

In early July, negotiations took place between representatives of construction workers and owners of construction companies.

On July 2, in the premises of the Gwiazda craftsmen association an agreement was reached to raise wages by 10 percent. The nuance was that the workers expected a raise for everyone, while the employers insisted that they had agreed only on unskilled workers. On July 7, at 17:00, another round of negotiations was held on this issue, now in the City Hall’s assembly room, but again no agreement was reached on the salary increase for everyone. At the same time, the locksmiths' strike continued, and on July 9 they managed to raise wages and to limit the working day to 9.5 hours, which was agreed upon in the premises of the same Gwiazda Association.

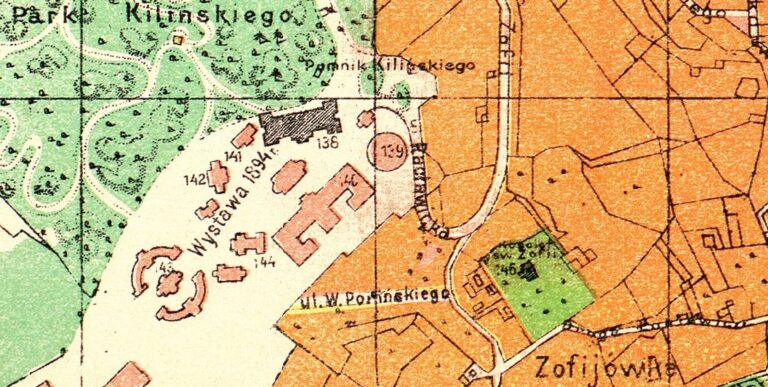

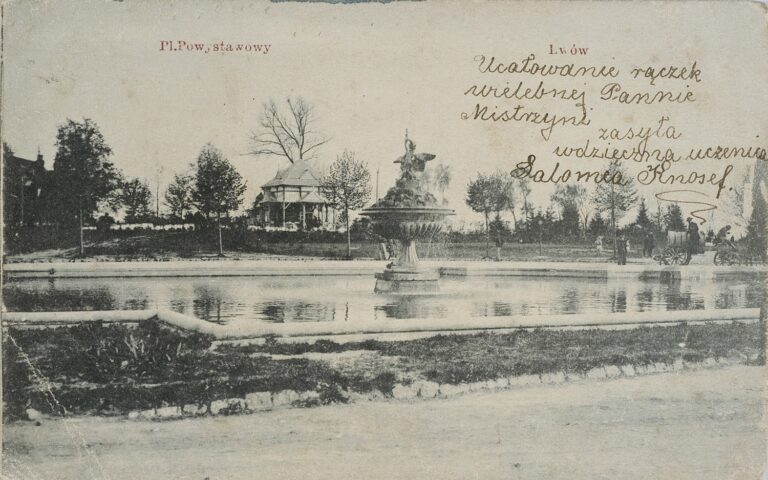

On Monday, July 10, at 16:00, workers gathered in the Music Pavilion in the post-exhibition area. These premises were allowed to be used by the president of the city of Lviv, Michał Michalski. In the presence of the head of the industry department, the workers elected a committee to organize a strike. It included two day labourers, one scaffolder, four bricklayers, two carpenters, two stonemasons, and engineer Artur Hausner. Politicians Teofil Melen and Aleksander Lisiewicz were also present at the meeting.

Striking construction workers on the territory of Stryi Park

The workers demanded a fixed minimum wage for a 9.5-hour working day for men and women. Women were to carry lime for a maximum of 4 bricklayers, and if it was necessary to climb to a higher floor, for a maximum of two. For male and female workers, the rule of 14-day notice of dismissal was to be fixed. Moreover, stonemasons were to treat women better and not use offensive words towards them. At the same time, lower wages were demanded for women, obviously, taking into account their lower productivity when doing heavy physical work.

Additional requirements were that local workers should be hired first, while non-local workers should be hired provided there was no alternative. The "lump payment" (that is, for the entire volume of work at once) was to be cancelled. Overtime work was to be paid at a double rate and to last no longer than from 7 p.m. to 4 a.m. with a one and a half hour break. The lunch break was to last one and a half hours.

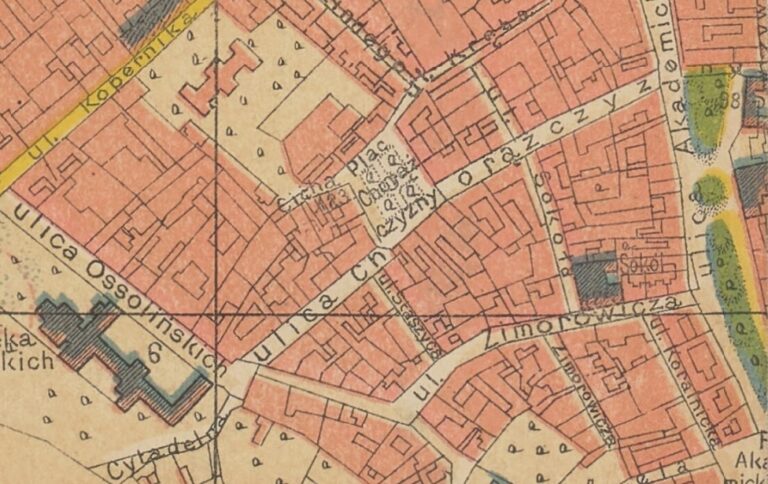

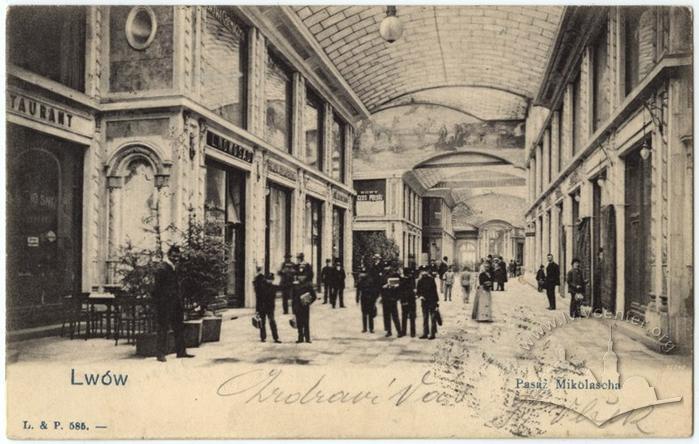

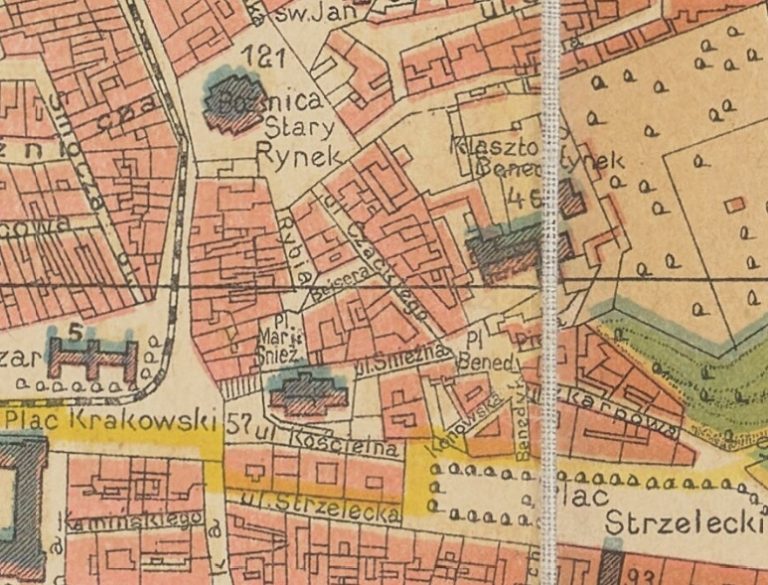

After the meeting, the participants decided to go to the Mikolasza passage, where there was an assembly room belonging to metalworkers, to allegedly discuss the situation with protests in the Kingdom of Poland. Most likely, the real reason was the kiosk of the nationalist newspaper Słowo Polskie that regularly criticized socialist and labour actions, which part of the workers wanted to visit again after the march through the city center following yesterday's shooting and pogrom. Singing workers' songs, the strikers went to the city through ul. Racławicka, ul. St. Sophia, ul. Zyblikiewicza, ul. St. Nicholas, ul. Akademicka, pl. Mariacki, ul. Kopernika, and ul. Ossolińskich. Then they planned to go to pl. Dąbrowskiego (now pl. Malaniuka), i.e. closer to the Słowo Polskie editorial office, but at the corner of ul. Staszica (now vul. Tomashivskoho) and ul. Chorąszczyzna (now vul. Skoryka) they were met by mounted and foot police units. After several calls to disperse, the police used their sabers and drove the workers to ul. Cytadelna and ul. Ossolińskich (now vul. Stefanyka), several of them were detained and released after checking their documents.

In the end, the Słowo Polskie kiosks in the Mikolasza passage and on ul. Tańska (now vul. Rudanskoho) were nevertheless affected. Another part of the demonstrators went to ul. Berka Joselewicza (now vul. Mayera Balabana) and broke the windows of the Judisches Tagblatt editorial office and of the Zion society. There were some troubles on the streets until approximately 23:00.

On Tuesday, July 11, starting at 10:00, even those workers who did not know about the strike stopped working.

The first stage of the strike: meetings, marches, negotiations

Despite the fact that during the first week the number of strikers reached more than 7,000 people (400 women, 2,500 stonemasons and carpenters, the rest were unskilled workers), the employers decided to make no concessions and to insist on the terms reached at the beginning of the month. Moreover, this was constantly repeated at meetings, as well as through the press and announcements.

The workers also regularly, almost every day, held meetings in the Music Pavilion, where they discussed the current situation, the employers’ proposals, and the search for support. Occasionally, representatives of the City Council or officials of the governor’s office were present at these meetings too. On July 14, it was decided to register the meeting participants and to give them certificates, because "various persons were sneaking in among them, instigating them to adventures." About 1,500 people signed up on the first day.

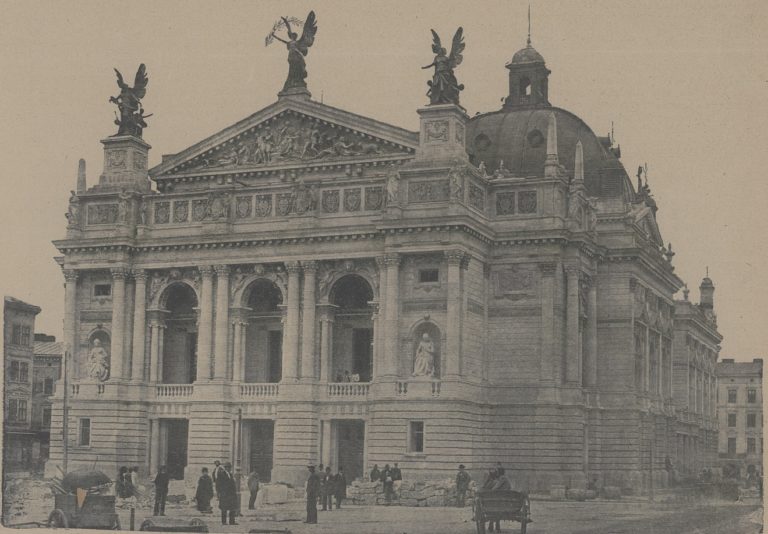

After the meeting, as a rule, there was a procession to the city center and a rally near the City Theater, the City Hall or the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. From the very beginning, the organizers warned the strikers against reckless actions and provocations. Moreover, during these marches the police not only accompanied the strikers’ column but also heavily guarded the editorial office of the Słowo Polskie. However, such advice did not always help, and even Semen Vityk, one of the leading figures of the PPSD (Polish Social Democratic Party), was sentenced to 7 days in prison for inciting against the government in one of his speeches. After some time, the marches to the city center no longer looked as militant as at the beginning, the strikers being exhausted both physically and morally. After two weeks without work (and therefore without pay), the workers used to go to the city center rather to "demonstrate their plight."

Meanwhile, negotiations continued, mainly through the mediation of the authorities. The representatives of the strikers asked the city president to intervene, while the employers appealed to the governor to influence the workers. Then a delegation of workers (Artur Hausner, Aleksander Lisiewicz and others) visited the governor. Subsequently, the industrial inspector of the governor's office spoke with the strikers and employers. The workers also held meetings in the City Hall, in the presence of City Council officials. After ten days of unsuccessful negotiations, the owners of the construction companies began to demand that the workers elect another group of negotiators, offering new rates that applied only to "local workers."

Solidarity, fraud, strikebreakers, rumours and propaganda

At the same time, the employers appealed directly to the workers and residents of the city. They had appeals printed and placed throughout the city in which they urged the strikers to adhere to the agreements and to work. Later, the strikers began to put up similar posters. In the announcements of company owners (which were sometimes signed on behalf of "Polish workers"), it was said that one should free oneself from the dictate of the social democrats and not listen to internationalist agitators. Besides, rumours about possible pogroms in the Jewish quarters were fueled, which was especially alarming due to the recent pogroms in the Russian Empire.

The strikers, in response, put up their own posters, where they assured that they were not planning any pogroms and that rumours were being spread by provocateurs hired by the employers. In the end, an interesting thesis was raised at another meeting in the Music Pavilion: "If the workers wanted to express their indignation somewhere, they would find a place outside the poorest quarters."

These talks about a possible pogrom coincided with a strike by Jewish butchers, who demanded lower wholesale prices. Accordingly, there were disruptions with kosher meat. The butchers decided to organize a union in order to buy goods without the mediation of wholesalers. The latter, on the other hand, decided to sell their goods through separate outlets. The butchers tried to explain to customers that meat was expensive because of suppliers and because the government limited imports, promoting exports to Germany.

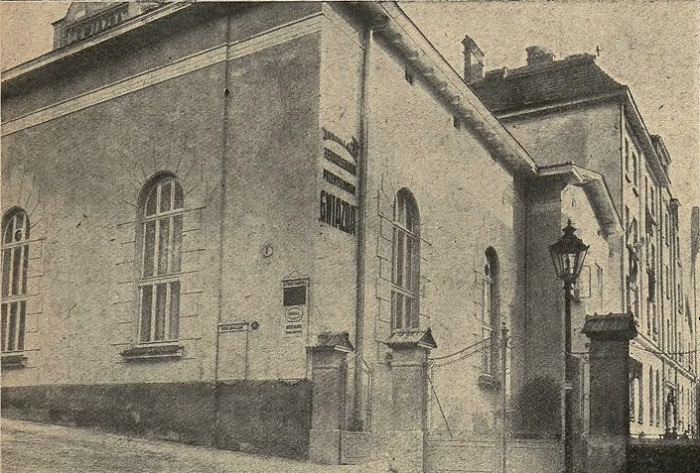

From the very beginning of the construction workers’ strike, swindlers appeared in the city, collecting donations allegedly for the workers. The committee regularly appealed through the press and announced that funds could be transferred only through the Ogniwo Association at ul. Ossolińskich 15.

Alongside the cases of fraud, there were examples of solidarity and sacrifice. Stonemasons decided to join the strike on July 12, but then they were discouraged from this step. Then the stonemasons decided to give 10% of their earnings to support the strikers. Later, as a sign of solidarity, about 100 people employed in paving the streets went on strike too. A week into the strike, butchers’ and bakers’ representatives came to a meeting of construction workers and also declared their readiness to strike. In the end, after two weeks of the strike, many workers' associations decided to help the strikers with money, and if the latter’s demands were not heard, to stop work as well. Thus, the prospect of a general strike became real in the city. Meanwhile, the committee decided not to support the strikers with money but to centrally buy and distribute bread to them.

However, this solidarity was not always total and not always voluntary, regardless of the fact that the organizers constantly warned against conflicts with non-striking workers. So, on July 13, about 300 strikers noticed three carpenters working on the bicycle track near the post-exhibition area. Two of them managed to hide in the Excise Service building at the Stryiska turnpike, and the strikers only broke windows there. One was beaten quite seriously, he could not move on his own and had to wait for the arrival of doctors. On the following day, a group of workers tried to "drive away from work" three carpenters who were repairing one of the pavilions in the post-exhibition area.

On the eve of the mass Sunday rally

On July 19, the striking workers gathered in the Music Pavilion to discuss, in the presence of the magistrate’s industrial inspector, new proposals from the employers. These were recognized as even worse than before the strike, so they decided not to return to work. The situation was tough, and it was difficult to keep calm. In addition, it was decided to contact the president of the city and ask him for permission to gather "in the city" and not far from it, in the post-exhibition area. On the same day, at a rally near the monument to Mickiewicz, Teofil Melen stated that it was the employers who would be responsible for possible riots, as their demands could not be met.

On the following day, the president of the city of Lviv, Michał Michalski, tactfully refused the workers. He explained that such meetings of workers could only be held indoors. There were no premises of the required size in the city center. Moreover, gatherings in the open air belonged to the sphere of "politics", thus requiring the permission of the governor and an application three days before the mass event.

On July 21, a photo shoot was organized during the meeting in the Music Pavilion. After that, the participants discussed the city president Michalski’s refusal, marched near the cadet school to the Rynok Square and dispersed. On Sunday, July 23, the social democrats announced meetings in workers' associations, as well as a possible general strike in Lviv starting next week. The meetings were planned in the premises of the Zgoda carpenters' association on ul. Skarbkowska, in the Ognisko printers’ association on ul. Łyczakowska, in the bakers’ association at the Rynok Square 12, in the female workers' association Naprzód at ul. Krakowska 8, in the metalworkers' association in the Mikolasza passage, in the traders' association at ul. Sobieskiego 28, in the association of painters at ul. Śnieżna 2, in the association of shoemakers at ul. Dominikańska 9, and in the association of butchers at ul. Ormiańska 29.

In the meantime, the employers formed new proposals. The dialogue, however, was limited to the strikers’ declaration: if the owners of the companies wanted the same order of work as in Vienna, the payment should be similar. The employers did not agree to this.

On July 22, the industrial inspector summoned the strike committee to discuss the revised proposals. The foremen and the owners gathered in the City Hall, where they talked to representatives of the magistrate. They agreed that it was difficult for workers due to inflation and rising prices in Lviv, but wages could not grow without increasing productivity.

Bread was distributed in the post-exhibition area until 20:30., so there was no march to the center. All the more so as the situation was becoming more and more tense, and the leaders of the social democrats persistently urged the strikers not to gather in groups on the city streets and not to confront the police.

These appeals, however, were not very effective. That week, a group of 50 strikers attacked a stonemason who was working near his own house on ul. Pijarów. After someone hit the stonemason with a brick, he fled into the house. Then the strikers broke the scaffolding and the plaster stucco and took away the tools. Another case happened when the strikers found out about a stonemason's assistant who had decided to work in the kitchen of the horse tram line director. They broke into the apartment and took the strikebreaker to the association premises on ul. Ossolińskich. There they forced him to lie down on the pool table and beat him with a cue, then making him kiss the pool table.

Both cases were investigated by the police, and one of those who hit the strikebreaker with a pool cue was arrested in his flat on the very next night. Also, on pl. Bernardyński, the police detained (but soon released) a group of strikers who also tried to disrupt the work of strikebreakers. In addition, the police arrested a railway worker who pretended to be a striking construction worker and extorted money from pubs and shops.

Sunday, July 23, 1905

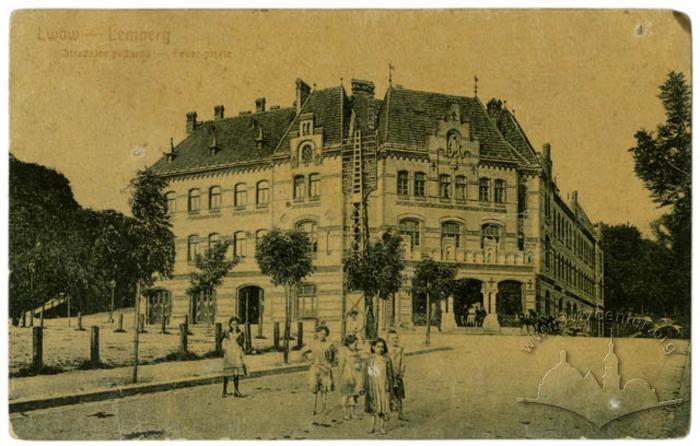

On this day, the authorities mobilized the police and the 95th Infantry Regiment. The soldiers were deployed on ul. Czarneckiego in the old firefighters’ barracks and in the courtyard of the police building. Since the idea of a general strike gained more and more supporters, the leaders of the social democrats themselves decided not to force this topic at the Sunday meeting. In addition to meetings in the associations mentioned above, furriers, watchmen and woodcutters also gathered in the morning.

At 10:00, the associations held short meetings in different places, where they adopted identical declarations of support and solidarity with the strikers. In some places they collected money, while in other places they decided to donate one day's salary to the construction workers' support fund.

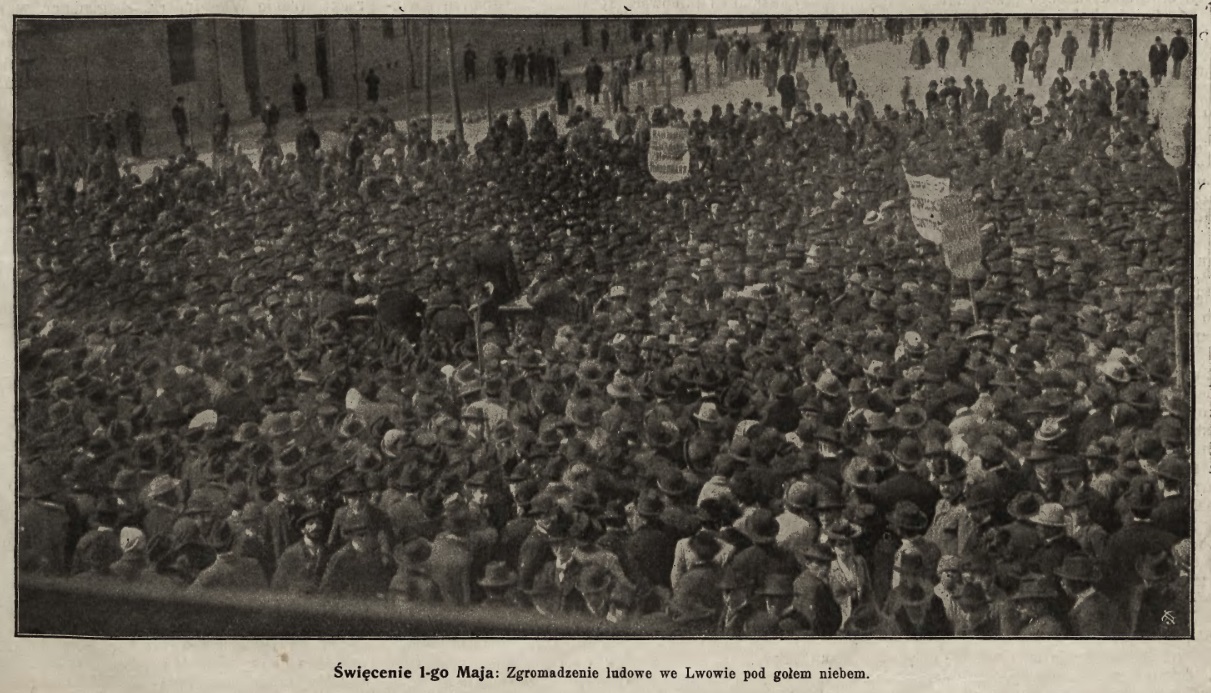

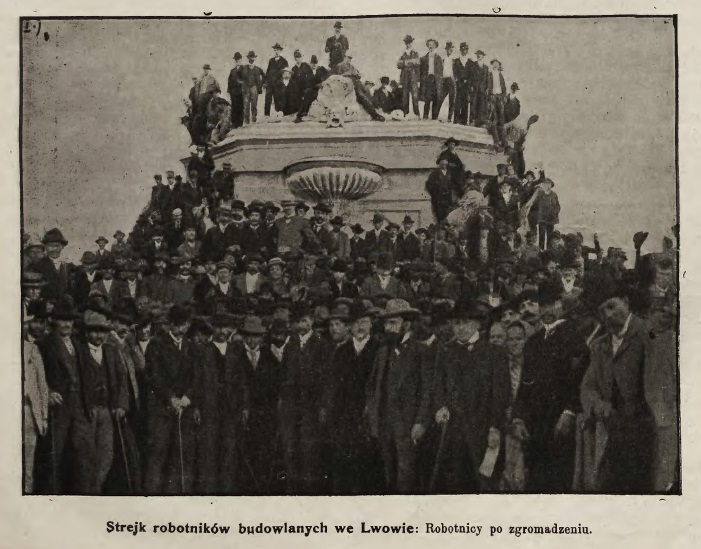

After that, the participants of these meetings marched to the post-exhibition area, where the strikers' meetings were traditionally held in the Music Pavilion. The march of printing press workers was especially notable, as about a hundred women marched in their column.

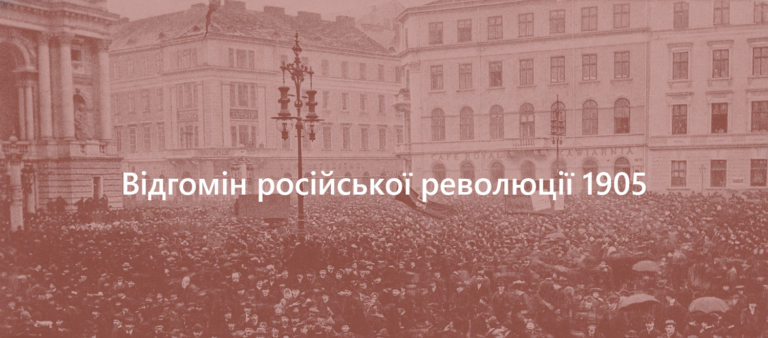

The construction workers voted to continue the strike and then marched away, singing the "Marseillaise" and the "Red Flag." At the head of the column a red spade decorated with green branches and red ribbons was carried. A rally was held near the City Theater, where the leaders of the social democrats, in particular Semen Vityk, condemned the city-wide strike and called for calm. Around 3 p.m., people dispersed. The Sunday march was really very massive, since even the government-run newspaper Gazeta Lwowska reported about 6,000 participants.

On the same day, the tailors’ association held a meeting in the premises of the Gwiazda association. Some of those present wanted to help the strikers financially, using money from the association's mutual aid fund. The others were against it and, in order to prevent voting, simply left the meeting.

Meanwhile, two gatherings took place on ul. Beisera (now vul. Rybna) in the premises of the Jewish association Brüderlichkeit. Jewish bakers gathered in the morning; a general assembly of Jewish workers was held in the evening. These gatherings were organized by the Jewish social democrats. The leaders of the construction strike were criticized at the meeting for not coordinating their actions with the Jewish workers. Therefore, Jewish workers involuntarily became strikebreakers, that is, exposed to conflict with Christian workers. It was, to put it mildly, surprising, as two weeks had passed since the start of the strike. Nevertheless, the meeting decided to transfer one day's earnings to the strikers and wait for the decision of the Jewish social democrats.

The third week of the strike: fights, skirmishes, a commotion on the Rynok Square

On Monday, July 24, after the Sunday rally, there was no march to the city. Instead, at the morning meeting, the organizers asked the strikers not to beat those working and not to take away their tools. Instead, they should be “in a comradely way” explained that they were harming the common cause. At lunchtime, the members of the strike committee had a meeting with the governor's advisor, the industrial inspector having failed to reconcile the parties to the conflict.

On Tuesday, July 25, in the afternoon, posters appeared in the city through which the owners and foremen called on workers to return to work on Thursday, July 27. They listed new conditions (with some concessions), assuring that these were general rules and not just "for locals." This was an important nuance: the employers could no longer hire those coming from outside the city for less money.

On the following day, at a meeting in the Music Pavilion, the workers rejected this proposal and went on a march to pl. Mariacki, where Artur Hausner addressed them. It happened late in the evening, since bread was distributed to the strikers in the post-exhibition area until 8 p.m., and many hungry people ate it while walking. As usual, the column was accompanied by about 50 policemen.

The workers claimed that back in February they prepared a memorandum to which the owners did not respond until July. They also claimed that the employers did not want to communicate directly with any group of negotiators and even tried to bring back the agreements actual before 1902. For example, it was proposed to abolish the 14-day notice rule for dismissals, which the construction workers had won during the previous strike. The workers were not satisfied with the proposed division into groups in which pay did not depend on qualifications, as well as with the division into locals and non-locals, not to mention the Vienna work regulations while maintaining the Lviv wage rate.

On the same day, Wednesday, July 26, clashes resumed, as more and more construction workers returned to work out of desperation. In several places, those working retreated under the onslaught of the strikers, while on ul. Janowska, where a canal was being constructed, the police chased the attackers away. The police also arrested two swindlers who cheated money "for the strike." Besides, the members of the employers' commission, which was involved in the development of the proposals, decided to withdraw their mandates, claiming threats from the workers.

On Thursday, July 27, the employers confirmed that they would negotiate only through an intermediary, the governor's adviser. They even said that they were ready to stop all construction works that year. The governor's office decided that the City Council was able, by virtue of its powers, to adopt labour tariffs that would be binding for both employees and employers, as well as to introduce special documents for construction workers without which it would not be possible to get a job.

The workers, who were on that day walking from the post-exhibition area through ul. Sapiehy, ul. Gródecka and ul. Karola Ludwika, planned to hold a rally on the Rynok Square. However, ul. Galicka was blocked by a police unit, so the strikers turned onto pl. Mariacki. There, as Semen Vityk was speaking, the police began to push back the demonstrators, clearing the horse-drawn tram track. Then a military unit with bayonets approached, so the organizers barely restrained the workers from a possible conflict. As the government-run periodical Gazeta Lwowska explained, the column was not allowed to go to the Rynok Square because an electric tram ran there, which was dangerous. On pl. Mariacki, the police were forced (without drawing their sabers) to clear the way for the horse-drawn tram, as the passengers were indignant and this could provoke a conflict. Instead, the demonstrators resisted and shouted: "We are hungry, let the tram not run." It was even more interesting with the military. It was a patrol consisting of 4 soldiers and 1 officer. Their task was to ensure that no military personnel joined the rally.

On Friday, July 28, the foremen and owners of construction businesses met in the City Hall. They refuted some accusations of the strikers (in particular, about "non-local" and "local" workers), rejected the demands of the strike committee again and decided to send a delegation to Vienna.

At the same time, groups of strikers walked around the city and chased away strikebreakers. At the neighbourhood of Znesinnia, where three construction sites were being worked on, a fight broke out, so the gendarmes and the police arrived. A commotion broke out among local residents, one of the strikers was seriously injured and another was arrested. On ul. Rappaporta, the police arrested a few men who had attacked stonemasons. In addition, at wood warehouses striking woodcutters drove away those who cut wood there, including those who worked for private individuals. In total, during the day, the police arrested over 10 strikers and about 40 vagabonds.

The most interesting thing happened, though, on the Rynok Square. At 11 a.m. a panic broke out at the market there. Hooligans and pickpockets (according to another version, paid provocateurs) started shouting near the Baczewski shop that a crowd of strikers was "coming and robbing" and "the workers were killing, they were already going to the Rynok." At the same time, several teenagers attacked bread sellers from the side of ul. Ruska. The sellers began to quickly collect their goods, a stampede started, during the commotion, milk and sour cream were spilled by the sellers, cheese, berries and fruits were scattered, eggs were broken, and the owners closed their shops. Shouts informing that everything was calm did not save the situation. Peasant sellers with tears in their eyes ran to the courtyard and corridors of the City Hall. So in 10 minutes, as the press reported, the poorest suffered losses.

The newspaper Dilo concluded that thieves and homeless people had started to take advantage of the strike, beginning to arrive in Lviv en masse. The brutal method of "establishing order" by the police only increased the tension in society.

On Saturday, July 29, 1,200 loaves of bread and 700 buns, which were provided free of charge by the "Under the Falcon" bakery, were distributed among the workers. Indifference on the part of the deputies of the City Council was discussed (one of the deputies responded through the press that he sympathized with the builders but did not want to deal with the leaders of the social democrats).

The rally at 20:00 near the monument to Mickiewicz was held rather for the public than for the strikers themselves. The organizers made sure that the horse-drawn trams ran smoothly. Speakers assured that even after three weeks of strike, the workers would behave calmly and peacefully and that provocations were organized by the owners of construction businesses. They also announced getting financial aid from Krakow and Vienna.

Nevertheless, after the previous day's commotion, very few peasants came to the market on the Rynok Square with their goods to sell. And on Sunday, July 30, it was decided not to organize a march to the city at all, limiting the action to distributing bread.

The end of the strike

On Monday, July 31, the strikers, through Józef Hudec, appealed to the president of the city of Lviv, Michał Michalski, with a proposal for negotiations. Apparently, they had made certain concessions, since on the same day, after lunch, a commission consisting of both employees and employers started working. Meetings lasted from 4 to 9 p.m. On Tuesday, August 1, the commission met again in the City Hall headed by Michał Michalski and in the presence of the industrial inspector.

The understanding was not very profitable for the workers. However, the democratic press wrote about the absence of serious riots (as a credit to the organizers) and the low quality of construction in Lviv (due to the employers). Now the latter had to hire only those workers who had certificates. Dismissals were allowed on Saturdays, not after 14-day notice, but with mandatory payment of salary. The salary also grew insignificantly, "lump jobs" (at a separate rate) remained, fixed deductions to the Sick Fund and to the workers' association were established.

On Tuesday, August 2, Artur Hausner, Ignacy Ewaryst Daszyński and Józef Hudec came to the strikers' meeting at the Music Pavilion with these conditions. They said that they were not imposing anything, at the same time threatening with the gravity of the moment and the responsibility for the fate of thousands of people. Their words about the workers’ victory were met by the crowd with clear dissatisfaction. The committee members threatened to resign from their mandates, saying that then the strike would drag on for several more weeks. Many ordinary workers were in favour of continuing the struggle. In the end, despite shouts and uproar, it became clear that the skilled stonemasons were mostly in favour of the strike, while the assistants and unskilled workers would rather return to work. Then, before the final vote, the leaders spoke separately with the stonemasons. Remarkably, as a result, everyone voted for ending the strike. That is, it is difficult to talk about any kind of democracy when the crowd decides the issue by raising their hands. At the end, the "Red Flag" was sung and 1,000 loaves of bread were distributed. At the same time, on Tuesday, August 2, the strikers returned to work.

During the strike, the Słowo Polskie was almost the only newspaper that openly criticized the workers. The bloodshed of 1902, which should not be repeated, was also mentioned there, while the strikers were compared to homeless people wandering around the city. At the rallies in the city center, allegedly, the public consisted mostly of the unemployed for whom the speeches delivered by the social democrats were simply a free spectacle. The marches of the demonstrators themselves were messy, and people participated in them more out of compulsion than due to an idea. After all, but for the pressure from the activists, many workers would be happy to return to work. The rest of the periodicals, if they did not present the party position, described the situation in detail and with a sense of empathy. Actually, this could be considered a victory of the social democrats, which they told the strikers about at the last meeting in the Music Pavilion.