In the period of the autonomy, granted to Galicia by the Habsburgs, Lviv became the center of confrontation between two national projects: the Ukrainian one and the Polish one. Jews, the second largest community in Lviv, also held public actions in the city, but unlike the first two groups mentioned, they did not claim an exclusive right to this territory.

Instead, Ukrainians and Poles did not just compete, they literally fought for the right to this city and province. The former claimed that Lviv was "the city of Prince Leo, the ancient capital of Galician Rus", while the latter declared it "the capital of the freest part of divided Poland."

Polish anniversaries

Obviously, Poles, who were numerically superior in Lviv and controlled the City Council, had more opportunities to promote their point of view. In symbolic terms, the "authorities" in Lviv were Polish. In addition, Lviv became the center of Polish emigration from Russia and Germany, as well as the center of anti-gentry, democratic political activity in contrast to the "conservative" Krakow. In this situation, the Poles of Lviv felt obliged and stimulated to take even more active part in all-national Polish politics.

When mass political events began to take place in Lviv, Polish activists immediately started to adopt imperial practices, thus becoming the authorities on a symbolic level. Thus, the civil guard replaced the emperor's grenadiers, and torches were used to greet not only Francis Joseph but also national poets. When rituals were used in European capitals to turn their subjects into a nation, the same thing happened in Lviv, adjusted for the fact that the city still belonged to the empire and there were several national projects in it.

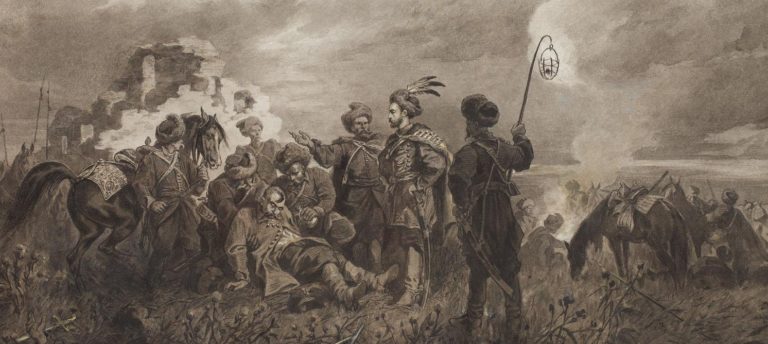

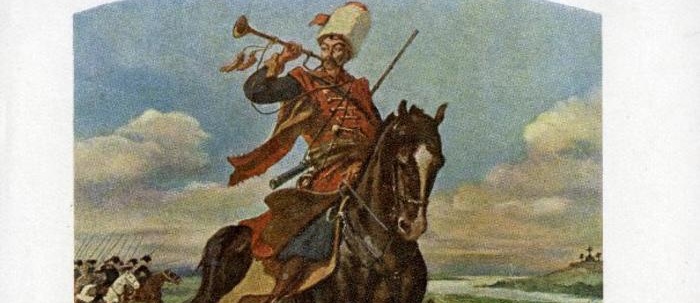

Many of the events organized by Polish activists were dedicated to important historical dates. References to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in addition to being interpreted as exclusively Polish history, allowed them to talk about democratic traditions, a "common home for peoples" and "ancient freedoms."

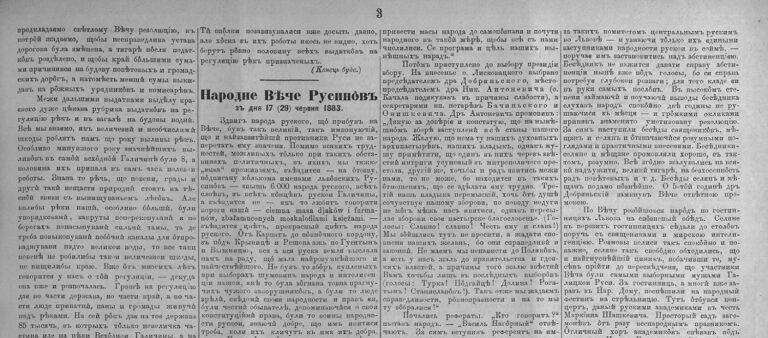

Ruthenian assemblies

Ukrainians adopted the imperial, European and local Polish experiences, attaching their own specifics to it. Primarily due to the small number of Ukrainians in Lviv, Ukrainian events took place mainly in "national enclaves", namely, societies and churches, coming out into the urban space rather rarely.

To go out "to the city", "national assemblies" were used. Sometimes, due to the mobilization of peasants, they managed to gather several thousand participants and demonstrate some "strength." Assemblies were also timed to coincide with memorable dates or current events. This practice, by the way, changed the meaning of the term "assembly" (ukr. viche), which originally meant a meeting of delegates devoted to a specific issue, where reports were read out and those present had to approve something like a resolution or an appeal; later, however, it was used to mean a political demonstration.

Another way of public politics used by Ukrainians was participation in student, socialist or workers' demonstrations.

Reactions to current events

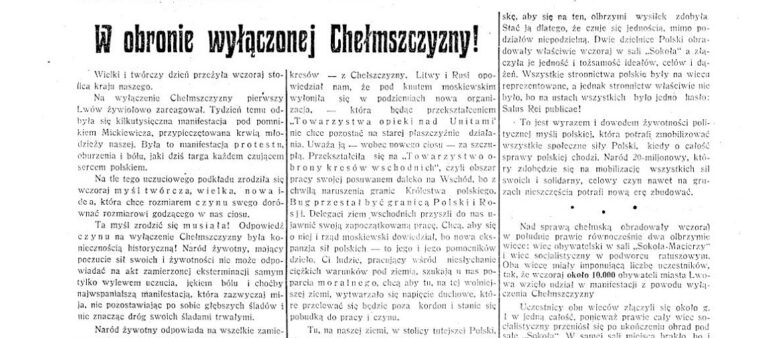

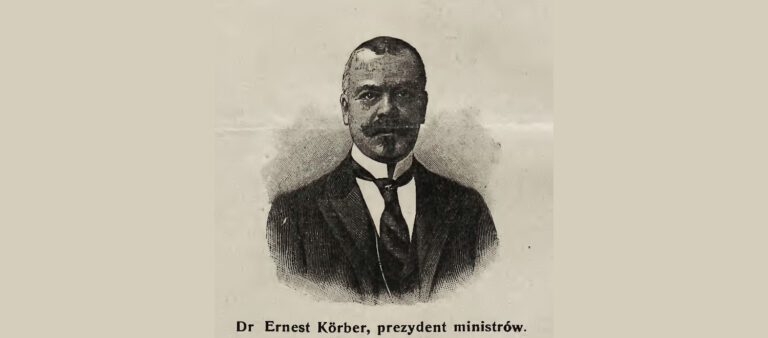

There were demonstrations caused by some current events, like spontaneous Polish rallies of protest against the separation of the Kholm/Chełm Land from the structure of the Kingdom of Poland. Such a manifestation of solidarity with the Poles living in the Russian Empire symbolically erased the existing borders and returned the former ones. Ukrainians, in their turn, protested during the visit of Prime Minister Koerber, who "offered Ruthenians and the whole region to the Poles to be profaned."

The University issue: language and representation

The main "topics" of the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation were political representation and language use. There were regular protests in favor of electoral reform, liberalization of legislation and expansion of voting rights. The most intense and bloody manifestation of the language issue was the events at Lviv University.

From the Ukrainian point of view, Polish politicians held two winning positions at the same time. To an outside observer, they positioned themselves as victims of the imperial policies of the Russians, Germans, and Austrians. However, in relation to Ukrainians in Galicia, they acted as typical colonizers and used the same shameful practices that they opposed in the German and Russian empires, probably taking their cue from Hungarian politicians who acted in a similar way in "their" part of Austria-Hungary and visited Lviv quite frequently.

Militarization

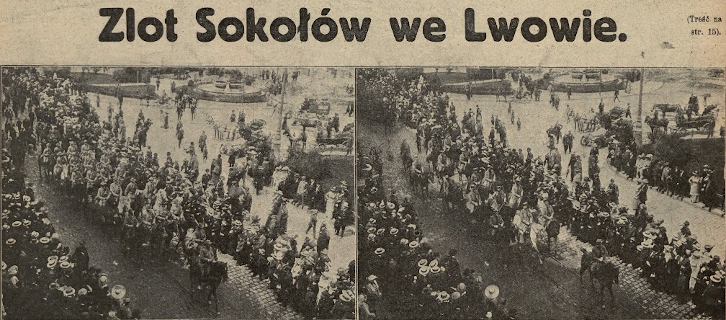

In the early 20th century, there was a distinct trend towards the militarization of political life. Paramilitary and gymnastic societies were actively developing, the role of firefighters (who were supposed to defend their homeland and not just to extinguish fires) was redefined, and sport was interpreted as a way to "harden the nation for the future struggle." Preparations for a "just and liberating war in the future" were, however, carried out with a demonstrative assurance of loyalty to the Habsburgs.

Young people were particularly affected by the militarization, with increasing numbers of schoolchildren and gymnasium students putting on uniforms and taking to the streets during various celebrations to solve the "fate of the fatherland." Obviously, this created additional tension between Polish and Ukrainian youth, as it was almost impossible to remain neutral.

On the eve of the Great War

In the early 20th century, the former ideas of "liberation of Poland, Lithuania, and Ruthenia" were only a vestige in the form of a legend telling that all nations had been well off under the Polish leadership in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. During the First World War, when the future fate of nations was being solved, the Polish press often published lengthy texts that combined all previous attempts to formulate the national mythology of Polish Lviv.

They wrote about its "historical mission among Polish cities", and about the "bastion of European culture against Turkish and Tatar raids", and about its "location on the borders of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth" (although looking at the map, we can see that Lviv was in the center and not on the border). They also talked about "the center of the Polish Sejm in recent times" and "the capital of the Polish Piedmont", thus redefining the provincial self-government quite loosely.

The fact that during the Great War Lviv residents strictly adhered to pro-German and pro-Austrian policies was presented as a virtue of local Polish politicians. Finally, they concluded that since Lviv had donated a lot of money and "its children" to the Polish legions in the Austrian army, it could rightfully claim leadership in Poland.

The Ukrainian "mythology" was more modest and clearly relied rather on Vienna's support than on its own resources. In this, however, it looked organic as it continued a long tradition of helping the ruling Habsburg dynasty "deal with rebellious Poles." This was interpreted as gratitude for the liberation from corvée labor, for the elevation of the Greek Catholic Church's status, for guaranteeing (or at least declaring) equal rights for each nation in the province, and for effective emancipation in general. With the outbreak of the Great War and the Russian Revolution, Ukrainians in Galicia increasingly paid attention to the events in Kyiv, believing, not without reason, that the whole of Ukraine would be a more important ally of Vienna than Eastern Galicia and Bukovyna alone (Transcarpathia was out of the question, at least in the near future).

Street events during the Great War

We should mention the "street" as well, which was also written about during the Great War. In Lviv, during the period of autonomy, the "street" became an important and sometimes crucial factor in politics, as it was, for example, at the time of the "Kholm/Chełm Land case" or the solution of the University's fate. But then again, it was a "two-way road" that, apart from Poles, was also used by Ukrainians, so it was through the "street" that the latter, having no significant representation in elected bodies, were often able to influence actual politics.

Eventually, all this confrontation culminated in real fighting on the streets of Lviv in November 1918.