A series of religious celebrations dedicated to the Catholic jubilee was organized by the Lviv Metropolitanate of the Greek Catholic Church. In them, not only religious but also national affiliation was manifested and loyalty to the monarchy was demonstrated.

Religious celebrations in the era of nationalism naturally could not but turn into national manifestations, especially given this rather ambiguous reason: after all, the Union was perceived by many as an instrument of assimilation, if we proceed from the logic of the same nationalism. The Kachkovsky Russophile Society, by the way, completely ignored the event; similarly, it did not become something important for the radicals. In the end, many supporters of Russophilism were among the clergy (including the higher ranks) of the Greek Catholic Church.

On the example of this anniversary, we can see that, firstly, for the Ukrainians (Ruthenians) of Lviv, certain locations were defined where it was customary to demonstrate their identity: Greek Catholic churches. Secondly, if it was about mass events, a Ukrainian demonstration in Lviv could not do without the participation of peasants from the surrounding villages.

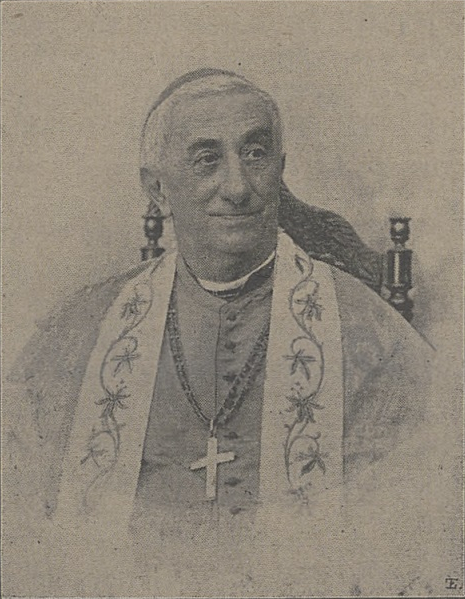

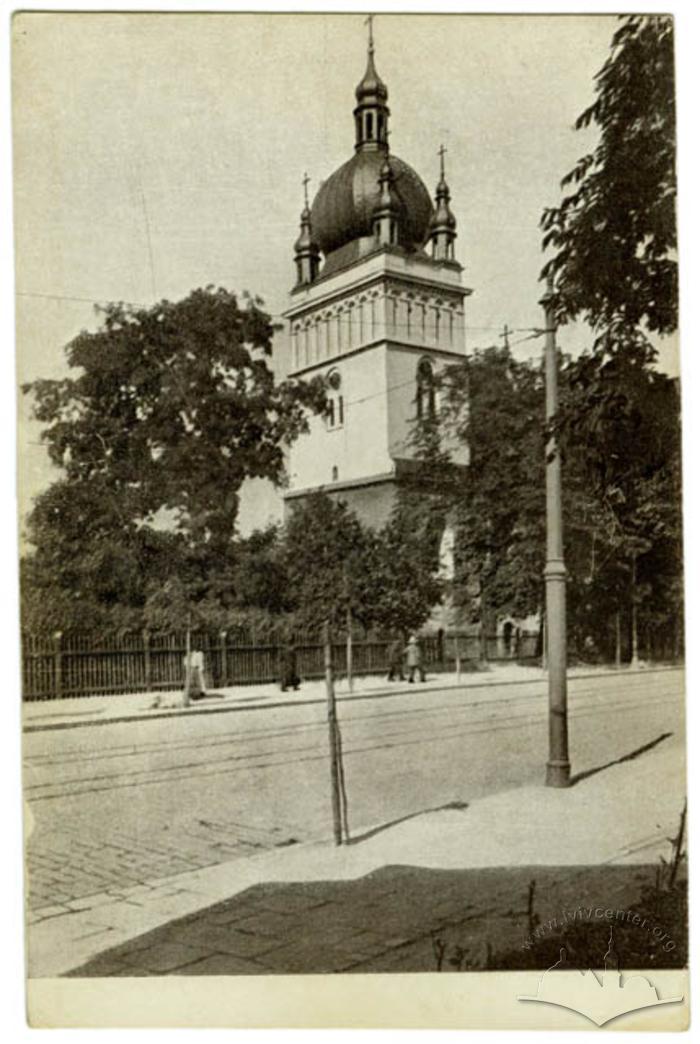

The celebration process itself was quite trivial. Church services and pilgrimages of the faithful to the few Greek Catholic churches of the city and its vicinities were organized. On September 28, 1896, there was a solemn service in St. George's cathedral, a march through the city to the church of St. Peter and Paul in the suburb of Lychakiv and back. On October 4, there was a march to the church of St. Paraskeva in Zhovkivske suburb and on October 11, to the Ascension church presided by Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych. At the same time, on October 11, liturgies in the Armenian and Latin rites were celebrated in St. George's cathedral.

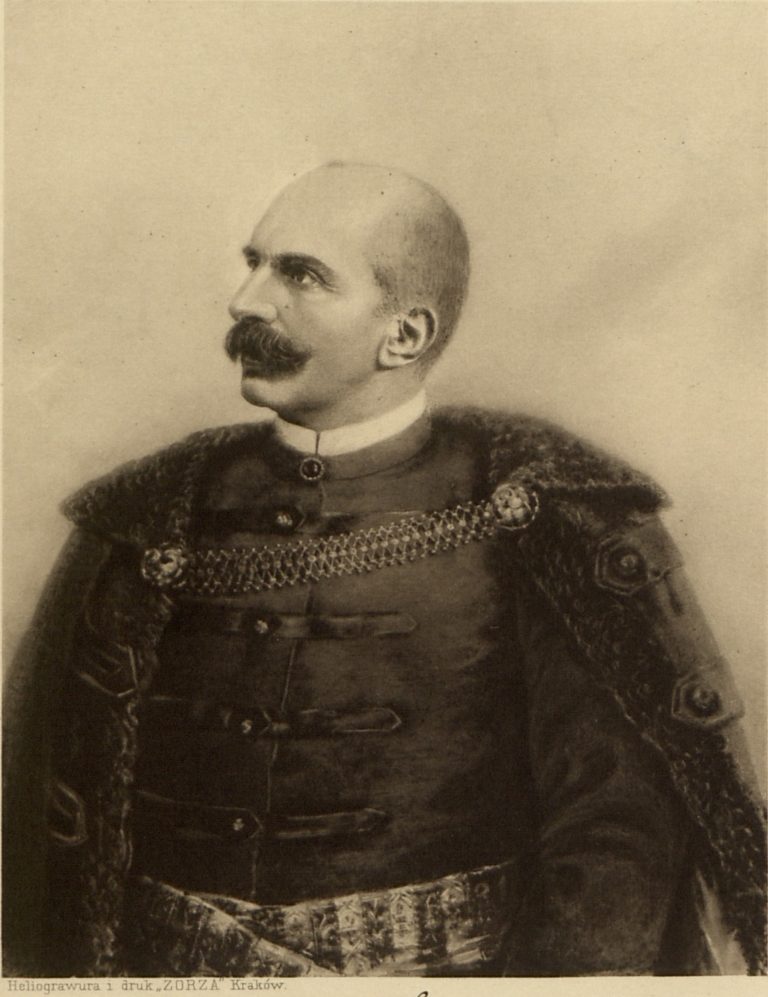

On October 13, there was another Liturgy in St. George’s cathedral. It was celebrated by Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych, who was assisted by Roman Catholic Archbishop Seweryn Morawski and other Catholic bishops.

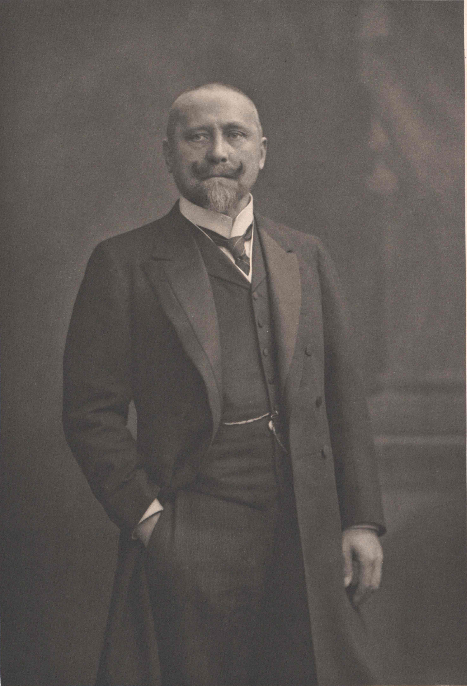

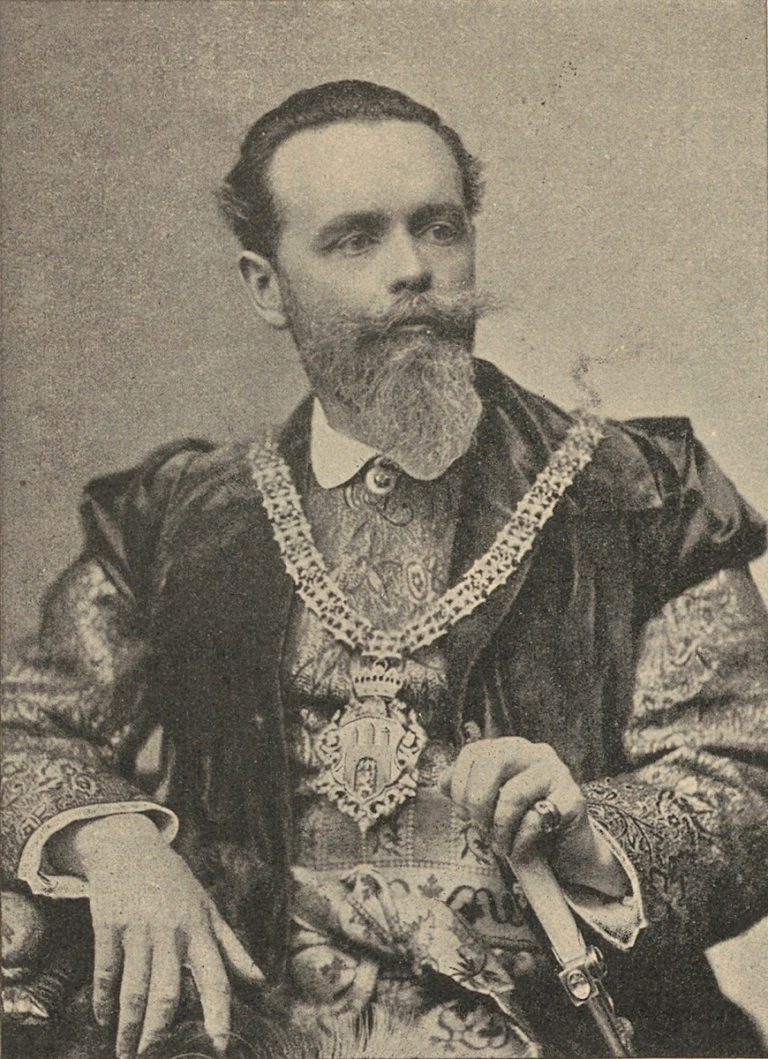

The biggest celebrations took place on the feast of the Protection of the Holy Virgin according to the Julian calendar, on October 14, 1896. Many villagers came to the divine service, occupying the entire churchyard in front of St. George's Cathedral. There were three metropolitans, delegates from throughout the province, representatives of the city and provincial authorities (governor Prince Stanisław Sanguszko, marshal Count Stanisław Badeni, vice president of the Provincial School Board Michał Bobrzyński, vice president of the Provincial Treasury Directorate Witold Korytowski, president of the city of Lviv Godzimir Małachowski and others ).

Andrey Sheptytsky, then still an abbot, spoke from the balcony to the people who had gathered in several solemn processions from the whole city as well as from the surrounding villages. In the afternoon, there was a solemn procession through the city with the Holy Gifts.

Two festive receptions were held in the metropolitan chambers: on October 13, in the afternoon, for 40 persons and on October 14, in the evening, for 80 persons, with obligatory toasts to the pope, the emperor and all Catholics. In the evening of October 14, the complex of buildings on St. George’s Hill was festively illuminated.

More important than the course of events is their interpretation by the Polish and Ukrainian press. The Gazeta Lwowska wrote about "the festivity in which the authorities and all the estates of the two Catholic nations took part", about the participation of school youth without division into the Ukrainians and Poles, about a joint prayer for the emperor. Instead, the populist periodical Dilo saw in the ceremonies not only a national Ukrainian manifestation but also a demonstration of examples of the Ruthenians’ unequal position. The procession to the church of St. Paraskeva was described as "a march of the clergy and church brotherhoods, with women in wonderful national costumes standing out." The events of October 11 were presented as "a great movement of the people, with the majesty inherent in our rite." Among the negatives are the speech of the Armenian archbishop in Polish and the ignoring of the processions by the Roman Catholic parishes whose churches happened to be on the route. According to the Dilo, church bells were "demonstratively silent", when Greek Catholics were solemnly passing them.

After all, the same event not only could be interpreted in different ways, different facts were also presented. Thus, regarding the "Protection of the Mother of God" (to which actually Sylvester Sembratovych's October 14 speech was dedicated), the Gazeta Lwowska wrote about "Protection for the Catholic Church", while the Dilo reported about "Protection for the Ruthenian Church." In addition, the Ukrainian Dilo did not mention the speech by the Basilian Soter Ortynsky on the topic "how a Catholic should behave in relation to the enemies of the faith and social order" (apparently, due to the non-acceptance by both populists and Russophiles of the reform of the Basilian monasteries by the Jesuits, because of which the Basilians were often treated as traitorous mankurts).

It is worth remembering that shortly before this celebration, an event called the Catholic assembly was held in Lviv, also timed to the 300th anniversary of the Union of Brest. Due to the Polish-Ukrainian contradictions, the Ukrainian clergy was not represented in large numbers at this event, and they did not hold their own special event. Probably, as was said in one of reports in the Dilo, it was due to fears of "politics and extreme elements" who could use the event to achieve their political goals. After all, many priests could have quite left-wing political views, so the demonstration of their unanimous support for the Vatican's position on social issues was a big question.

One way or another, the celebrations held by the Greek Catholic Church in 1896 demonstrate the difficult inter-ethnic relations in Lviv, where the Ukrainian community could demonstrate its presence in public space only by enlisting the support of peasants from the province. The Ukrainian public space was clearly marked as Greek Catholic, i.e. denominational. This was written about by both the Ukrainians and Poles, each group in its own way.