A mass event dedicated to the 300th anniversary of the church Union of Brest, held in Lviv in July 1896.

History

Although the event was timed to the 300th anniversary of the Union, the main reason for the Catholic Church’s activity was a reaction to the spread of socialism and the reduction of the church's influence on social processes. Actually, the Lviv Catholic assembly was the second one, since a similar event took place in Krakow in 1893. The participants declared their loyalty to the Apostolic See and spoke about Ukrainian-Polish mutual understanding based on belonging to the Catholic Church. They also emphasized the need to "knock out the ground from under the feet" of socialists due to the church's social teaching. What prompted them was, in the end, the Apostolic See’s active policy regarding left-wing ideologies, described in the 1891 papal encyclical Rerum Novarum.

The course of events

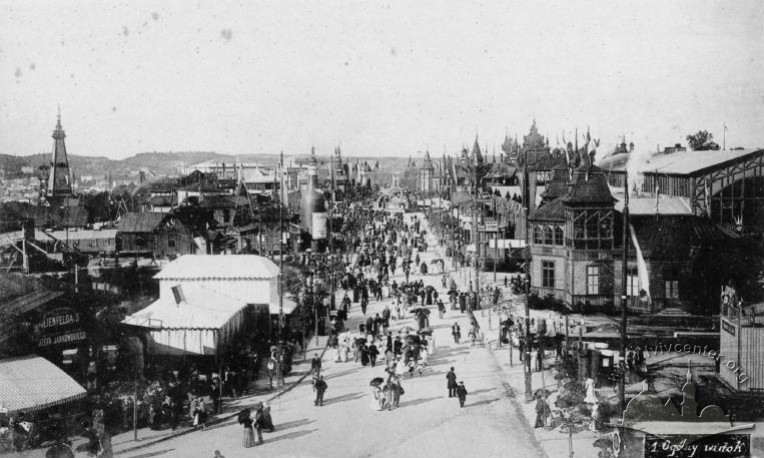

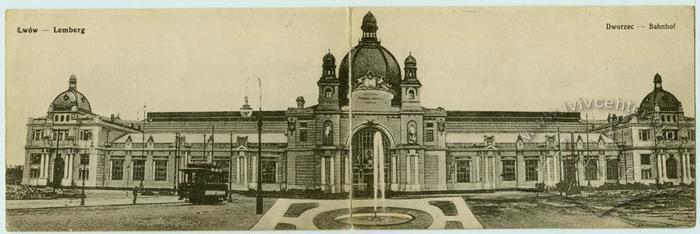

The press reported that an information office and a ticket office for the advance sale of tickets for the assembly were located in the Imperial Hotel. On the days of the action (July 7-9, 1896), tickets could be purchased in the industrial and music pavilions of the Provincial Exhibition, where all the events took place. There was also an information office at the railway station, which dealt with accommodation of participants in hotels and in both paid and free lodgings. Free food and accommodation was offered by the Association of Catholic Servants Skala on ul. Mickiewicza (now vul. Lystopadovoho chynu 28), paid lunches for participants of section meetings were offered by the Kremer's restaurant in the Kilińskiego Park (now Stryisky Park). Separate events included a demonstration of The Crucifixion (Golgotha) panorama in the exhibition area and a final charity banquet in the City Casino.

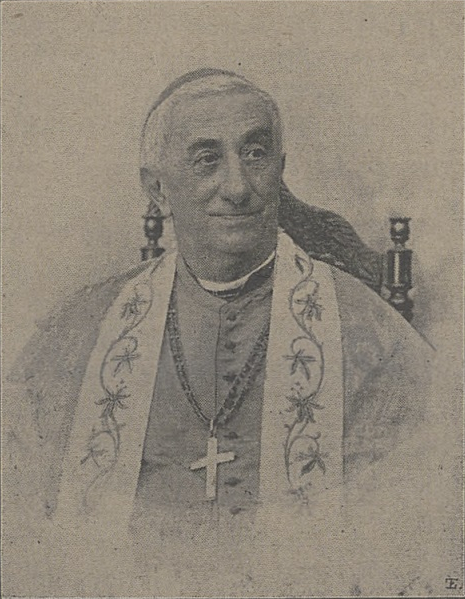

The assembly programme included, among other things, a welcome speech by the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Cardinal Sylvester Sembratovych, solemn services in the churches of three Catholic denominations of Lviv, section meetings in the industrial pavilion of the Provincial Exhibition and solemn ones in the music pavilion. The main topic of the meetings was the social issue. In general, however, the matter discussed was very broad and covered the issues of the church Union, the Christian family, country life, an economy based on Christian solidarity (mutual aid, insurance, social security of workers). Crediting, emigration, professional restoration of churches, the press, and school education were also discussed, as well as guardianship of orphans and prohibition of duels.

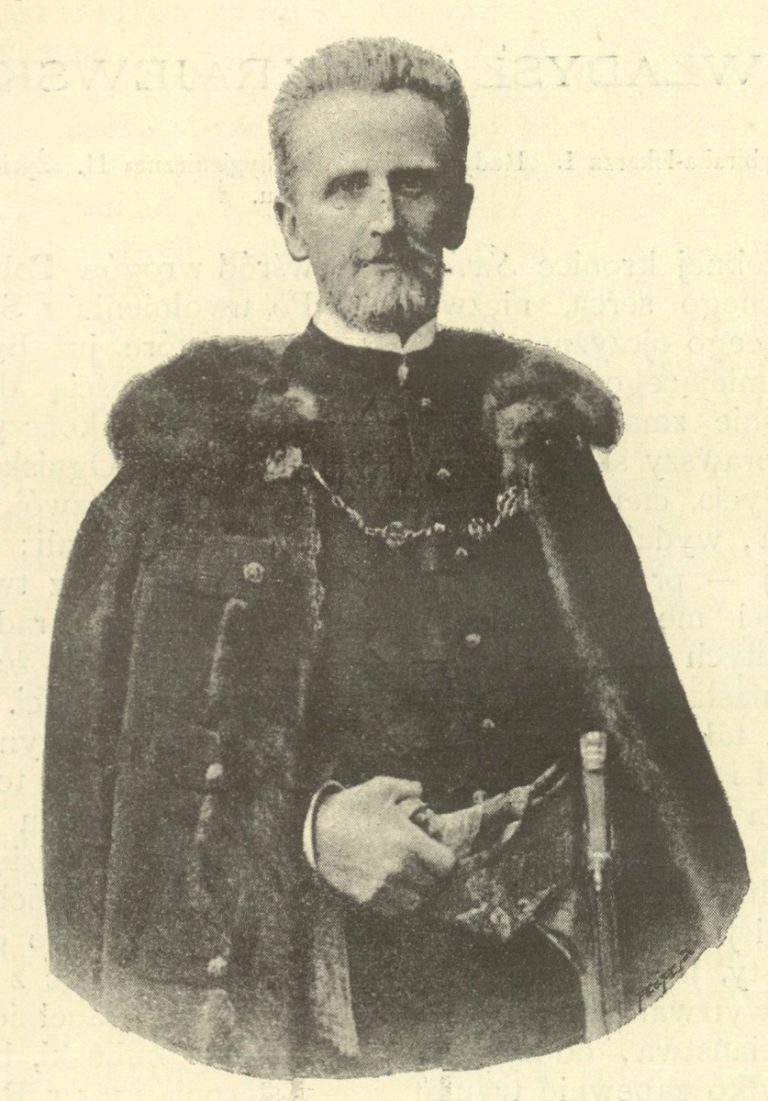

Although the Gazeta Lwowska reported about the event as a "gathering of the Catholic Ruthenians and Poles", the Ukrainian participation was, to put it mildly, not massive, even though it was also far from the complete ignoring that the Dilo reported. For example, Isydor Sharanevych, the senior of the Stauropegion Institute, was elected the vice-marshal of the event, Kyrylo Studynsky was the secretary, Oleksandr Barvinsky and Anatol Vakhnianyn gave speeches (that is, Ukrainian conservatives, the so-called "Old Ruthenians" and "Westerners", were present). Nevertheless, the absolute majority of around a thousand people present in the music pavilion at the opening were clergymen and "nobles and representatives of the first families of the province", in particular the Roman Catholic Archbishop Seweryn Morawski, the Armenian Archbishop Izaak Izakowicz, the provincial marshal Stanisław Badeni, the president of the parliamentary Polish Circle Filip Zaleski, the president of the city of Lviv Edmund Mochnacki, Prince Adam Sapieha, who was elected the marshal of the assembly, and others.

The assessment and significance of the event

The event assessment by the Polish and Ukrainian press was very different. Thus, the Polish Gazeta Lwowska reported the event as an example of unity between Catholics of different rites (despite "political and national differences"), mentioning the importance of the Catholic Church’s social work in the conditions of the growing influence of socialism, as well as the role of Catholic organizations and associations, the encyclicals of Pope Leon XIII and the church’s social policy. The Ukrainian newspaper Dilo brought the national issue to the fore. The 300th anniversary of the Union of Brest was interpreted not just as a date that coincided with a Catholic social event but as the actual reason for the event. Consequently, according to the Dilo editors, the event should have been a Ukrainian one to which the Poles could have been invited. Instead, it turned out to be something "utraquistic", actually, Polish, even aristocratic, where the Poles were once again able to demonstrate their leading role against the background of the loyal and passive Ruthenians. This opinion logically fit into the populist narrative of the "denationalization" of the Greek Catholic Church, along with Latinization, attempts to introduce celibacy, and the reform of the Basilian monastic order by the Jesuits. After all, in the autumn of the same year, the Greek Catholic Church organized its separate celebration (but not an assembly) timed to the 300th anniversary of the Union of Brest.

It is only logical that, based on assessments of this kind, the descriptions of the assembly itself were also different. The Gazeta Lwowska describes the pavilions of the Provincial Exhibition as "beautifully decorated, filled with the best representatives of the two nations", while the Dilo reports "a usually empty exhibition area with a few pavilions that have not yet been dismantled", where priests and aristocrats gathered, with few peasants around, and the premises being decorated "in papal and Polish national colours." The decoration was supplemented with a crucifix, busts of the pope, the emperor and the empress, and an icon of the Częstochowa Mother of God.

The small number of peasants was interestingly interpreted by the Dilo: it was so to prevent Fr. Stoyalovsky (a well-known supporter of left-wing ideas, later deprived of his priestly rank) and his ilk from using the event to promote their left-wing ideas and from "arranging a peasants’ assembly."

The only thing common to the two periodicals was a detailed retelling of the speech delivered by the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych. However, the "correct" accents were placed there as well. From the Polish point of view, the preservation of the Eastern rite in the Greek Catholic Church guaranteed loyalty to the church and resistance to "socialist and liberal influences", while from the Ukrainian point of view, the rite itself was valuable as a marker of national identity.

However, since the assembly was primarily a conservative event, the speakers made appropriate statements. The president of the city of Lviv, Edmund Mochnacki, spoke about Lviv as a bastion of Christianity and an eternally Catholic city. Archbishop Seweryn Morawski spoke about harmful Western ideological influences. They talked about "returning to the old Polish custom of praying with family and servants", about holidays "not in taverns but in Christian institutions"; about the need to prohibit Jews from producing and selling Christian objects of worship; about the fact that socialism destroyed the institution of the family making the worker jealous. There were wishes that schools would once again become denominational and religion exams would be compulsory. The main reason for emigration was not the needy financial situation of the emigrants but "the insidious activity of unscrupulous agitators."

The idyllic picture (ladies in the galleries, dignified gentlemen in the stalls, a group of peasants wearing folk costumes on a separate balcony) was completed by the final blessing of "Catholics belonging to various strata of the two peoples" by the three metropolitans of Lviv. After that, the celebration (for about two hundred people) was continued in the City Casino.

The Catholic assembly was one of the first mass events where contradictions between the Ukrainians and Poles were openly manifested and where the role of the church, or rather the religious affiliation as a national marker, played a key role. Although the confrontations of the early 20th century were still far ahead, the main trends were outlined quite clearly. These were, above all, subordination of the religious to the national and open criticism of the clergy who did not meet the demands of the contemporary politics. The main thing was that each of the participating parties had its own interpretation of events and remained in their initial positions regardless of their opponents’ actions.