The funerals of prominent persons in Lviv in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were mass, mostly national, manifestations. The funeral of Ivan Franko, a Ukrainian intellectual and "poet-prophet", was no exception. For the Ukrainians, this manifestation was unusual primarily due to the absence of peasants (which was due to wartime restrictions), as well as because of the position of the Greek Catholic Church, which, to put it mildly, did not support this event. However, quite remarkably, the absence of peasants and the resistance of the church did not affect the mass nature of the procession: Franko's funeral became one of the most massive Ukrainian events in Lviv before 1918. Moreover, the event was organized almost exclusively by the people of Lviv.

Preparation

The date of the last farewell was reported by newspapers in advance, inviting people to honour a prominent citizen. The Taras Shevchenko Scientific Society was involved in the organization, in particular, they informed the General Ukrainian Council in Vienna, discussed the place of burial, agreed on a posthumous mask and photographing the procession.

On May 29, special mourning meetings were held at the Shevchenko Scientific Society. On Tuesday, May 30, there was a rehearsal of the united choir in the Ukrainska Besida hall at ul. Kościuszki 1a.

Residents of Lviv were informed of Franko's death by newspapers and traditional posters with a death notice. Black banners were hung on the buildings of Ukrainian associations. An exhibition of Ivan Franko's works was organized in the Prosvita bookstore at pl. Rynok 10. Finally, societies and organizations individually called on their members to participate in the farewell ceremony.

Later, Franko's funeral was described in the press as a "magnificent demonstration", because "Lviv had not seen such a funeral for a long time." It is noteworthy that most of the 10,000 participants in the procession were local, as the state of war did not allow the arrival of large delegations from the province or peasants. There were delegates from various counties, school youth, members of societies, Sich riflemen: "the whole of Ukrainian Lviv". That's why, against the background of "urban clothes", which was not characteristic of Ukrainian demonstrations in Lviv, a girl in a Hutsul costume with a wreath "from friends in Kryvorivnia" stood out.

Course of events

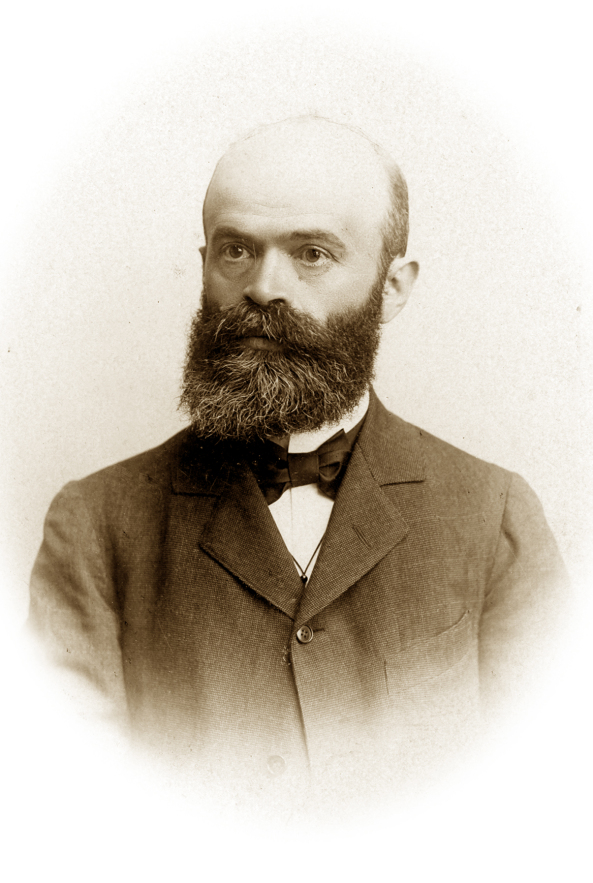

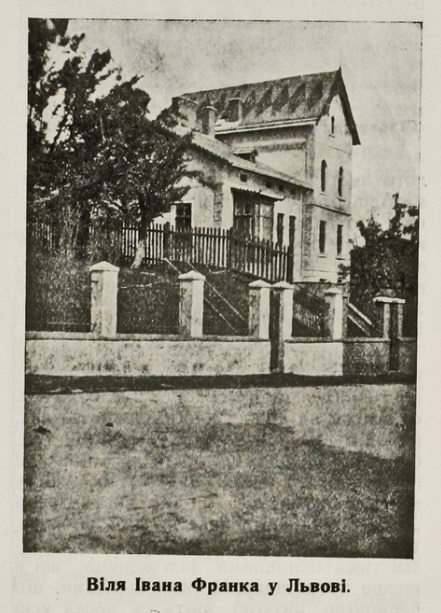

The ceremony began at 5 p.m. on May 31, 1916, from Franko's house at ul. Ponińskiego 4. The choir of Ukrainian societies was singing, led by Vasyl Barvinskyi, the coffin was carried by Sich Riflemen, a speech was delivered by Kost Levytskyi. Then the funeral procession went to the Lychakiv cemetery: school youth and Plast scouts, "falcons" in uniforms, women, the choir, a hearse with wreaths, another hearse with the coffin. The funeral was followed by "a friend of the deceased, councilor Karl Bandrivskyi", Ivan Franko's son Petro (a USR Legion officer), and "the brother of the deceased, peasant" Zakhar Franko. Next, the representation of the General Ukrainian Council: Kost Levytskyi, Kyrylo Tryliovskyi, Mykola Hankevych, then members of the NTSh, Oleksandr Barvinskyi, the editorial board of the newspaper Dilo, Ivan Trush with his wife Ariadna (daughter of Mykhailo Drahomanov), delegates from the province, Ukrainian intelligentsia. In the rear, there were "Polish friends of the deceased": the editor of the newspaper Kurjer Lwowski Bolesław Wisłouch, poet Jan Kasprowicz, member of parliament Jan Stapiński, ethnographer Henryk Bigeleisen and others.

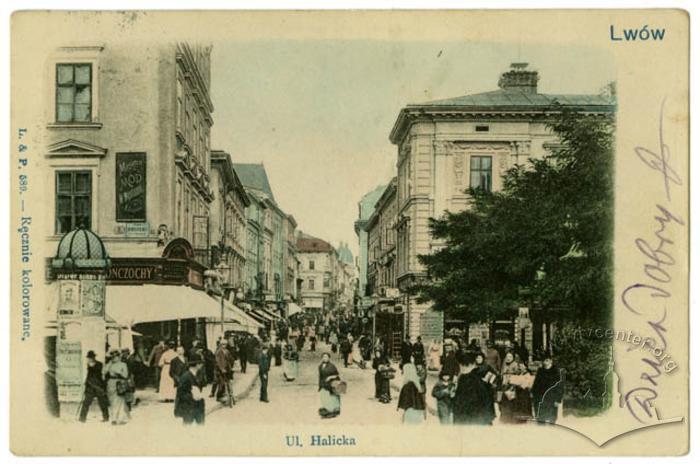

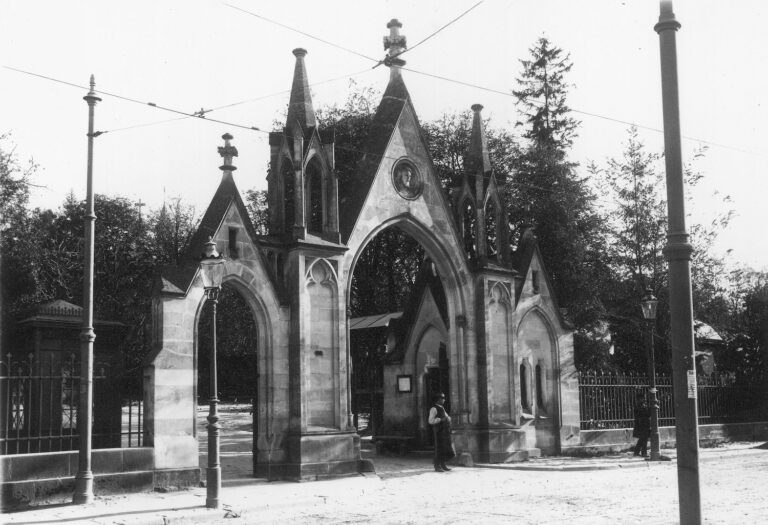

At 8 p.m., the procession reached the Lychakiv Cemetery, passing through the following streets: ul. Ponińskiego, ul. St. Sophia, ul. Zyblikiewicza, ul. Akademicka, pl. Galicki, pl. Bernardyński, ul. Pekarska. Here, the remains were again taken by Sich Riflemen and temporarily placed in the vault of the Sas-Motychynskyi family (in the autumn of 1916, the NTSh appealed to the Magistrate to allocate a plot for the poet's grave free of charge, but the remains were moved only in 1921).

Until 10 p.m., speeches were delivered: Oleksandr Kolessa spoke on behalf of Ukrainian cultural societies, then there was Mykhailo Lozynskyi, a member of the Dilo editorial board, Kyrylo Tryliovskyi of the Radical Party, Zenon Noskovskyi, a sotnyk of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, a "delegate from Volyn" (i.e., those of its territories that were occupied the Austrian army), Vasyl Ratalskyi from Drohobychchyna, Fed Fedortsiv from Ukrainian youth, Orysia Velychkivna (Iryna Velychko) who spoke about Franko's struggle for women's equality, Mykola Hankevych on behalf of Ukrainian socialists, Sydir Tverdokhlib on behalf of young writers and artists. Numerous telegrams were received as well.

This was the visible side of the funeral, which, however, was not as simple a matter as it might seem at first glance. Ivan Franko's reputation as an atheist and talk of his unfinished confession created problems with priests who refused to conduct the ceremony. Seminarians were forbidden to attend the funeral; consequently, a choir of seminarians could not take part either: hence the need for a joint choir of Ukrainian societies.

In the end, the priest Volodymyr Hurhula to whom Franko refused to confess the day before, agreed to bury him. The deceased's wife, Olha, was being treated for mental disorders, his daughter Anna was in Kyiv, his son Taras was at the frontline serving in a unit of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen. Of the whole family, only one son, Petro, an officer of the USR, could be present.

Nevertheless, Franko's funeral showed that when there was a conflict in the Ukrainian environment between representatives of the Greek Catholic Church (although in the absence of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi, who had been deported to Russia) and secular politicians, the latter prevailed. Political and national expediency and perhaps simple human relations dominated even such a purely religious event as a church funeral.

In addition, the Ukrainians demonstrated the presence of all the attributes of a "fighting and aspiring nation." The funeral was attended by the military, the intelligentsia, representatives of organizations, as well as the "masses of the people" even without the involvement of villagers (who could not be involved due to the wartime restrictions). Moreover, this was actually contrary to the position of the Greek-Catholic church hierarchy. All this was very unusual and was evidence of huge changes. The situation emphasized the fact that the Ukrainians in Lviv were no longer just "peasants and preasts" as it was customary to state in the 19th century, but a society with ambitions to fight for the city and in the city.

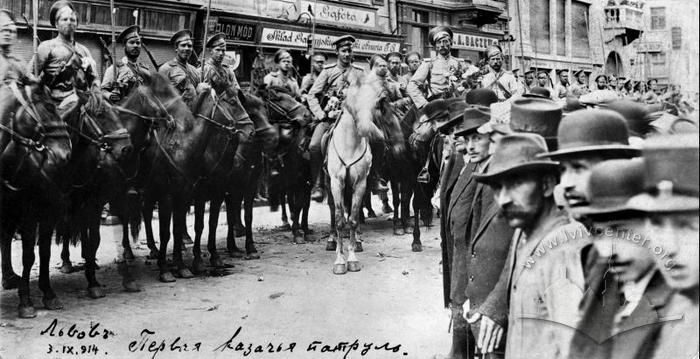

Besides, against the background of Ivan Franko's funeral, the degree of freedom available in Austrian Lviv can be realized. Even at wartime and under strict control by the military administration, the opportunities for national manifestation were enormous, compared to the period of Russian occupation. What follows is, for example, a description of the funeral of the iconic Ukrainian politician Mykhailo Pavlyk in occupied Lviv in January 1915 (from the memoirs of Yaroslav Levytskyi):

“Almost the entire Ukrainian intelligentsia, who was then in Lviv, gathered for Pavlyk's funeral. His funeral was the first “Russian” funeral in "liberated" Galicia. Both mounted and unmounted gendarmes arrived in huge numbers. Gendarmes were everywhere: in front of, around and behind the caravan. Mounted gendarmes were following. It looked like some prominent gendarme officer was being buried and not a poor Ukrainian writer”.