Two almost simultaneous events dedicated to one episode in history, the siege of Lviv in 1655, which demonstrate the confrontation between Ukrainian and Polish society in Lviv at that time.

On November 11, 1905, the Lviv City Council solemnly celebrated the anniversary of the "defense of Lviv from the Cossacks and Russians." On the following day, November 12, Ukrainians organized a rally in honour of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, which ended in clashes with the police.

Theoretically, given the very reason for the celebration, an understanding between Poles and Ruthenians was not envisaged. The only way to avoid confrontation could be to ignore this date; however, this did not happen. It should be remembered that in late 1905, the effects of the Russian Revolution were felt, including in Austria-Hungary. So, it is not surprising that mass riots and clashes with the police took place in Lviv. An additional factor of tension was the information about the Jewish pogroms in Russia, and that is why the celebration of the anniversary of the siege of Lviv by the Cossacks emphasized the fact of the Jewish presence in the city.

Organization and preparation of the celebration of the defense of Lviv

The Polish part of society celebrated the citizens’ victory, which showed their "loyalty to the Crown." Jews had the opportunity to celebrate the anniversary of "the salvation from the Cossacks." For the Ruthenians, this date was a reminder of the failed attempt to "be liberated from the Polish captivity."

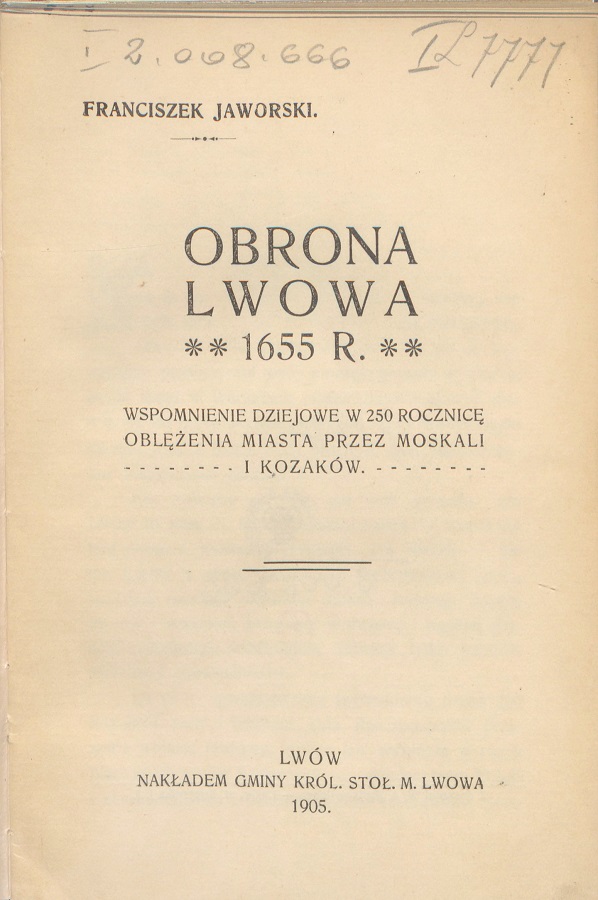

The idea of the celebration was discussed in the City Council in October 1905, when an organizing committee headed by the President of Lviv Michał Michalski began to meet, with the participation of five other city deputies. The program of events, which included services in churches and synagogues, a historical lecture in the City Hall and a series of lectures in schools, as well as publishing a brochure, was supported by the City Council with great enthusiasm. Companies, organizations, and corporations functioning in Lviv were invited to join the events. The dissatisfaction of the Ukrainians had no effect at this stage.

Although it is worth noting that attempts to divert the focus of attention from contemporary Ukrainians, their fellow citizens, were still made by the organizers, even through the wording "the siege of the city by Muscovites and Cossacks", in which neither Ukrainians nor Ruthenians were mentioned. Instead, "the burghers of Lviv, who in difficult times for Poland showed their courage and loyalty to the Fatherland, the king, and the church", were mentioned.

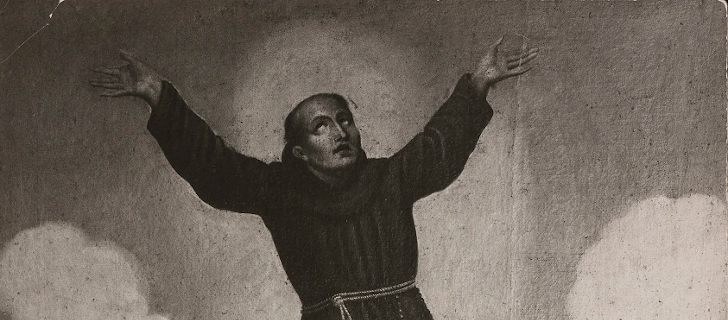

Saint Jan of Dukla defends Lviv from the siege of Bohdan Khmelnytsky. Wall image in the Bernardine church in Lviv

The course of the celebration

Saturday, November 11, began with a solemn service in the Latin Cathedral, where the Lutnia Society choir sang, and in the Armenian Cathedral.

At 5 p.m., a solemn meeting began in the City Hall, to which, in addition to members of the City Council, representatives of the clergy, including Auxiliary Bishop Józef Weber, deputies of the Galician Sejm and members of patriotic organizations were invited. The musical programme was provided by the Echo Society’s choir; Aleksander Czołowski, manager of the Lviv archives, gave an hour-long lecture on the siege of Lviv in 1655. A historical brochure on the events of 250 years ago by Franciszek Jaworski and a commemorative card issued at the expense of the city's Jewish community were distributed among those present.

At 7 p.m. a special programme began at the City Theater. The mentioned historical brochure was also distributed there, the event ending with singing of the anthem Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła.

The Ukrainian rally and clashes with the police

On the following day, Sunday, November 12, a Ukrainian rally was convened in the People's House. Officially, it was organized to honour the memory of Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and not as a reaction to the Polish events of the previous day. The rally was initiated by some populists, although not only their supporters but also sympathizers of the Social Democratic Party came. In total, there were, according to various estimates, from 2,000 to 4,000 people, including a lot of pupils, students, workers. There were also women and intellectuals.

The meeting was opened by architect Vasyl Nahirny and chaired by Fr. Teodor Bohachevsky, a deputy of the Galician Sejm; Yevhen Levytsky, the editor of the Dilo newspaper, spoke. In his report, he linked the situation of Ukrainians in Lviv to the history of the Cossacks’ struggle against the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and called the celebration of the defense of Lviv by the City Council an example of Polish chauvinism. Ukrainian societies in the province were recommended to hold thematic events dedicated to the history of Bohdan Khmelnytsky's campaigns. Separately, it was decided to send a telegram to Kyiv and to congratulate the Ukrainians there on the promised democratic transformations (that is, the impact of the 1905 revolution was felt). The rally ended with a performance of the anthem Shche ne vmerla Ukraina.

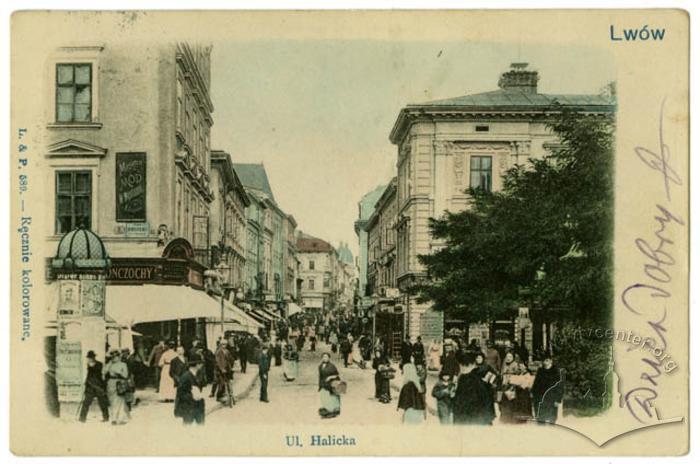

After the report, the participants left the People's House wishing to organize a demonstration near the City Hall. There were even calls to "finish what Khmelnytsky started." However, on the way to pl. Rynok, namely on ul. Trybunalska, the police detachment blocked the way for the demonstrators.

A skirmish took place there, with the Polish and Ukrainian press providing diametrically opposed information on the causes of the conflict. From the Polish point of view, the Ukrainians, seeing the police, decided to break through the cordon and started shooting revolvers. Then the police used sabers, the mounted police joining the dispersal. The Ukrainian press reported that the police cordon on the narrow and dimly lit street was a provocation, that there were no revolver shots but firecrackers ("shooting frogs"), and that the demonstrators were merely not given the possibility to stop. Moreover, events of this kind with the participation of Polish activists were not dispersed by the police.

As a result, five policemen sought medical help: two had their heads injured with stones and one was stabbed. Among the demonstrators were about 20 wounded; however, only one of them dared to see a doctor officially (although newspapers reported about chopped wounds made by sabers and about fractures due to a horse attack). This evening, six people were detained for disorderly conduct, illegal assembly and resistance to government officials; two of them were arrested.

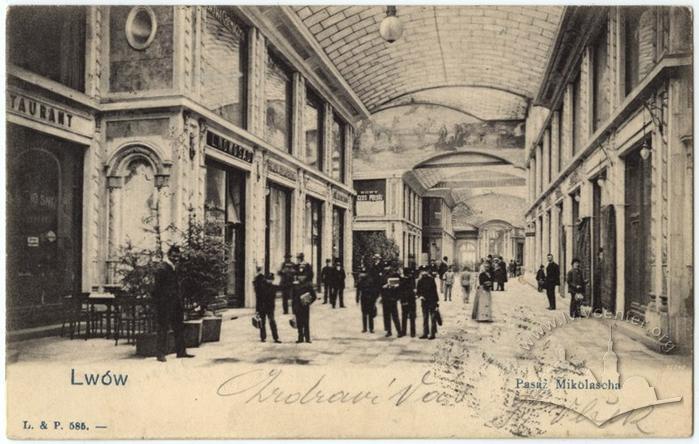

Some of the demonstrators still managed to reach pl. Rynok from vul. Halytska, but the police were waiting for them there as well. Therefore, about a hundred protesters, singing Ruthenian songs, went to pl. Mariyska. In the Mikolasz passage, they smashed the windows of the Słowo Polskie newspaper’s kiosk, and only half an hour later, at about 7 p.m., the police managed to disperse them completely.

The Ukrainian event from the Polish perspective

The Polish press contrasted the City Council’s events (allegedly peaceful and unpoliticized) with the Ukrainian rally. In particular, they wrote that even during the meeting in the People's House, the police commissioner intervened with demands to stop shouting "death to the Poles" and "let them disappear." Quite logically, Polish newspapers did not support the thesis that Khmelnytsky had twice tried to free Lviv from captivity.

The decision to go to the City Hall was considered by Polish journalists to be an example of anarchy when the organizers lost control of the crowd. They wrote that loud singing Shche ne vmerla and Ne pora, as well as shouts "To the City Hall!" caused panic in the surrounding streets. Jewish shops and gates of nearby houses were urgently closed.

The Ukrainian version

The situation was most fully covered in the populist newspaper Dilo. The rally was interpreted there as "a respectable people's demonstration and a worthy response to the provocative actions of the city council." Quotes from Yevhen Levytsky's essay were cited, for example, about "Polish-Catholic warring orders" or about "Lviv Ruthenians being betrayed by Latin priests." Khmelnytsky was called the liberator of Ukraine, who merely took pity of the city, so there was no question of any heroic defense. It was not without the influence of the Russian revolution as the Dilo noted that "it is dawning in the East, and the first rays of freedom have fallen on Galician Ruthenia."

The Dilo called the performance of the anthem Shche ne vmerla Ukraina on vul. Teatralna "a reminder to Polish chauvinists that the capital of the "one free part (apparently it was the Austrian part of the divided Commonwealth) is located in the land that has been Ruthenian since the beginning of time."

For several weeks after the dispersal of the demonstration, each issue of the Dilo published either the participants’ testimonies or information about the victims, eventually summing up with a transparent threat of street confrontation. If the Poles continued to provoke the Ruthenians with similar anniversaries, the newspaper insisted, they would end up by "an appropriate violence on the part of the Ruthenian element against Polish demonstrators in the provincial capital."

The reports in the Russophile magazine Galichanin were very colourful, starting with a statement that the "jubilee provocation" was organized by the City Council and ending with a comparison of Khmelnytsky with Suvorov. The latter was a rather risky step, given Suvorov's role in suppressing the Polish uprising of 1794. In the newspaper, however, this mention was not presented as an author's position, but was part of a report: allegedly, one of the participants in the rally had made this comparison in the People's House. Bohdan Khmelnytsky was described as a "glorious Russian hero" and it was predicted that "the Russian people will produce yet another new Bohdan the Avenger." The newspaper also wrote that in addition to the Ukrainophile anthems Shche ne vmerla and Ne pora, the demonstrators also sang a "radical hymn" Yakyi to shumnyi veter igrayet.

Even the ultra-loyal Ruslan newspaper supposed that the idea of celebrating a jubilee of the defense of Lviv caused unnecessary tension and was perceived by Ukrainians as a challenge. By the way, this is the only periodical that managed to critically consider the impact of the Russian revolution on the situation in Galicia. This was done not only in the context of intensification of politicians or radicalization of street demonstrations but also in relation to the interethnic conflicts that followed. The Poles were accused of substantiating their claims to some lands on the basis of "old parchments", that is, trivially instrumentalizing history in the era of self-determination of peoples (gradually dawning even in Russia).

The consequence of the anniversary was a further interethnic aggravation. Apparently, under the influence of revolutionary events in Russia, the degree of tension only increased, and the street confrontation looked like a real way out of the stalemate. Even the position of local politicians was far from moderate or willing to find a compromise.