It was the first time the event was celebrated in this format and interpretation. It demonstrated the growing popularity of nationalist ideas and the loss of the conservatives' ideological monopoly in Galicia.

Organization and preparation

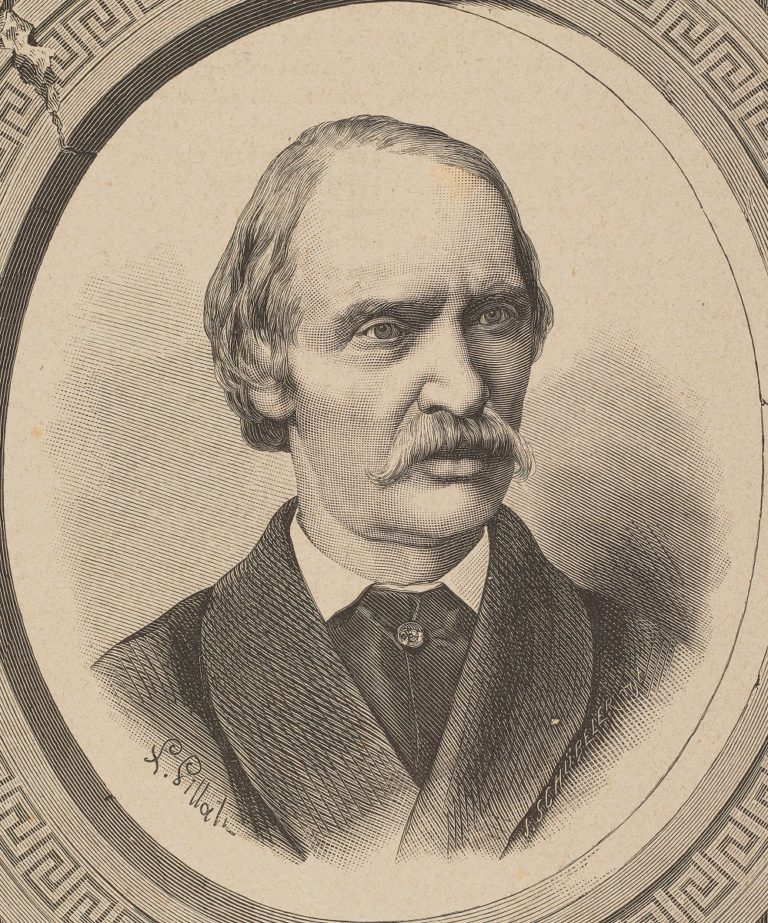

The program of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the November Uprising included lectures, press releases and a solemn celebration. The organization in Lviv was led by Otto Hausner, Piotr Gross, and Tadeusz Romanowicz, members of the Galician Diet. The organizing committee was formed in May, and the program was published in June, after the Diet voted to allocate funds for the reception of the Emperor.

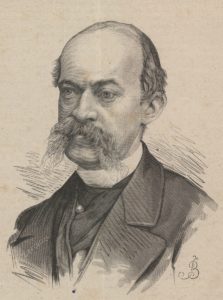

- Отто Гауснер / Otto Hausner

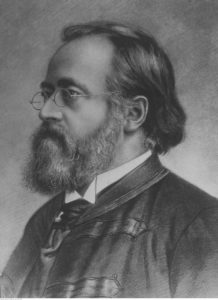

- Пьотр Ґросс / Piotr Gross

- Тадеуш Романович / Tadeusz Romanowicz

What was new was that the organizers began to interpret the uprising beyond the limits of the usual rational analysis. They began to speak of a "spirit of struggle," of an example for future generations. They also began to treat Lviv as "the capital of the region where the Poles have the right to be Poles." After all, other partitions of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (Russian and German) did not have the opportunity to hold such events.

The conservatives, who interpreted the uprising as a "tragic mistake," were furious. Especially since the fate of the Emperor's upcoming visit was at stake. They remembered that the emperor's visit in 1868 had been canceled because of the excessive autonomy of the Diet. The conservative newspaper Czas (Krakow) wrote that only sick people could celebrate tragedies and national disasters. In general, the new interpretation violated the ideological dominance of the conservatives.

The liberal Lviv-based periodical Dziennik Polski opposed the conservatives, criticising the "black and yellow" (imperial) servility. Emigrant organizations in Western Europe and the United States also expressed support for the organizers.

There were also problems with the police, who tried to limit the distribution of materials about the celebrations. The authorities were particularly concerned about the lectures that were to be held in the assembly room of the City hall. On the one hand, the lecturers did not provide any prepared notes, which made it impossible to check their loyalty. On the other hand, canceling the lectures would have caused public discontent. The proposed solution was to limit the lectures to a small group of invited people. The organizers got creative here as well: they decided to sell the invitations and use the money to support the veterans of the uprising.

The course of the event

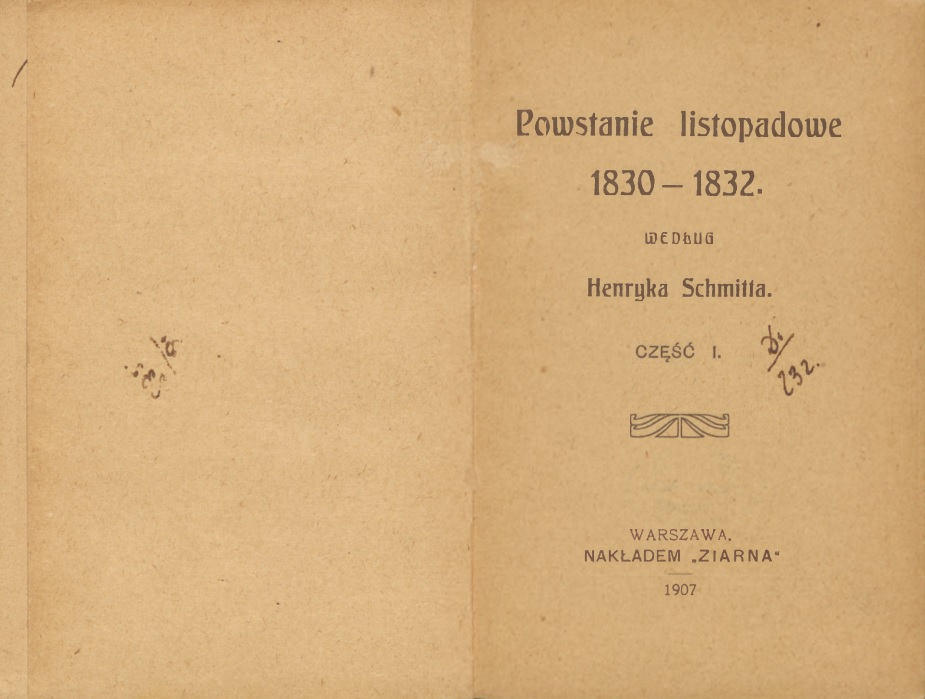

Of the five lectures held in the assembly hall of the City Hall in November 1880, four were recorded by the police as "unsuccessful". They were given by Count Leszek Dunin-Borkowski, Tadeusz Romanowicz, and Henryk Schmitt. The lectures lasted 30-45 minutes each, with up to 400 listeners, "mostly women," who responded with "weak applause." The police concluded that nationalist ideas were unpopular in society. After all, the lectures were about the right of a nation to revolt and the fact that the Polish conservatives' policy of "organic labor" would not lead to future independence. They also discussed the fact that the November Uprising, a "great struggle," could not be reduced to an "immature and mistaken protest," as representatives of the Krakow School of History claimed.

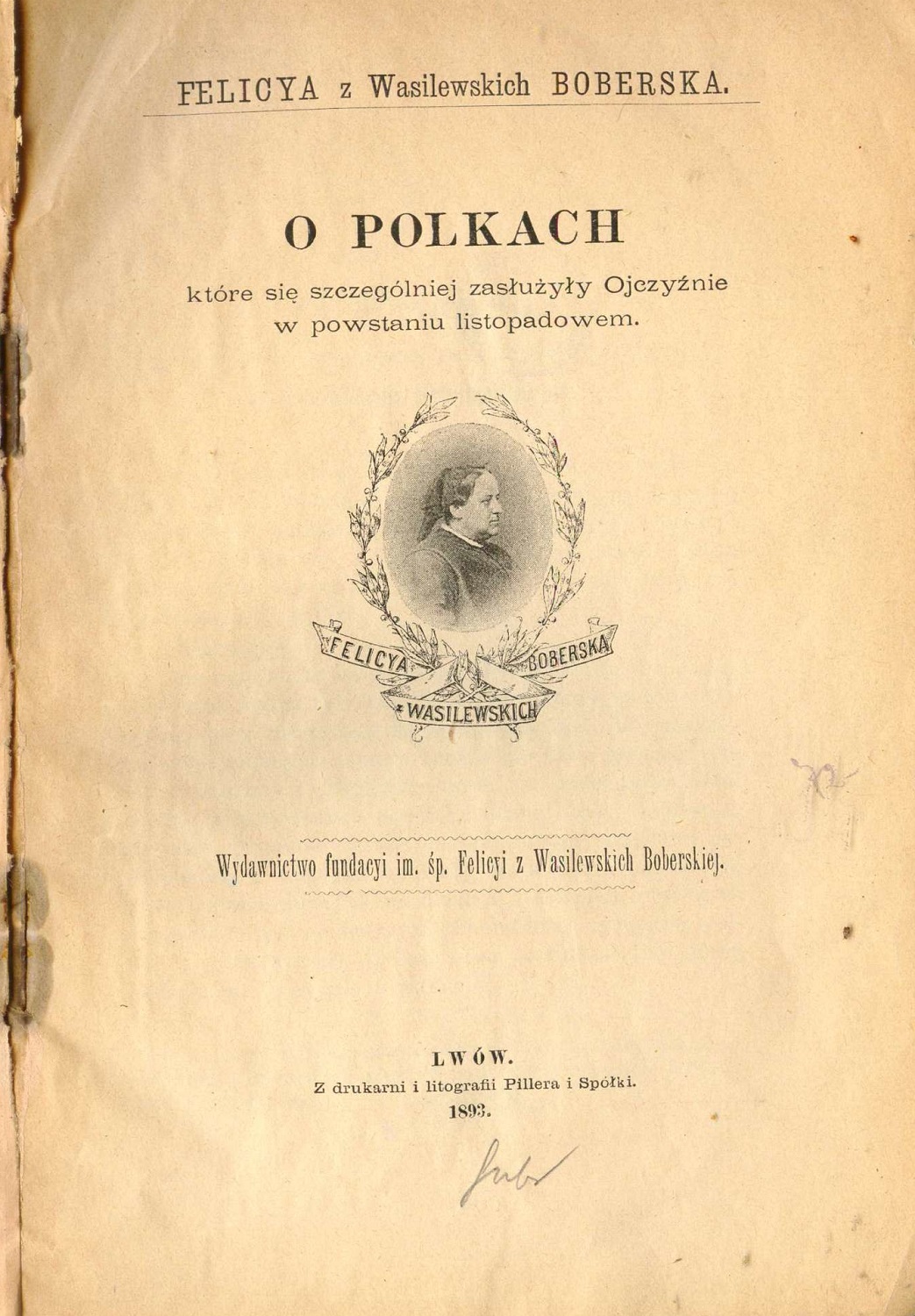

The fifth lecture, given by activist Felicja Boberska, was more successful. The 700 people in the assembly hall were enthralled by her words about the role of Polish women in preserving national identity and women's participation in the uprising. She called on the audience to raise children in the spirit of those who died for their country. The lecturer also criticized conservatives who did not accept women in public life.

The lectures were attended by the leading figures of the democratic movement. However, due to censorship, they could only communicate with those who were physically present at the lectures. The authorities did not allow any printed materials or publications in the press. The result, although limited, was considered a success in mobilizing the urban population.

On 28 November 1880, Jewish academic youth organized a service in the liberal synagogue on the Staryi Rynok square in memory of those who had fallen during the November Uprising. Veterans, members of the City Council, and many non-Jews came to the synagogue and sang the Psalms of David in Polish.

The next day, November 29, the main events took place. At 9 a.m. a mass was held in the church of the Dominican monastery, attended by the participants of the uprising, students of universities and schools, as well as the ordinary residents of Lviv. The square in front of the church and the surrounding streets were filled with people. The service was conducted by priest Józef Nowakowski from Zhovkva, who had been an artilleryman during the November Uprising. Members of the Lviv City Council, dressed in Polish national costumes, kept order. After the service, the patriotic song "Boźe coś Polskę" was sung in the church. It is noteworthy that the shops in the city were closed at that time.At 11 a.m., about 200 veterans marched solemnly to the City Casino. The Harmonia City choir greeted them with a military march there. An amateur choir performed music cantata, specially composed by the poet Kornel Ujejski.

At 11 a.m. about 200 veterans marched solemnly to the City Casino. There they were greeted by the Harmonia City Choir with a military march. The amateur choir performed a musical cantata composed by the poet Kornel Ujejski.

Otto Hausner's congratulatory speech, in which he criticized the current politicians and clergy, was forbidden to be published in the press. However, the censors allowed Count Leszek Dunin-Borkowski's words about the blood of the martyrs, the country, future generations, national memory, etc. to be published.

Each veteran present received a commemorative medal. It depicted an allegorical figure of Poland holding a shield. The inscription read "For Our Freedom and Yours;" on the other side it read "Poland to the Heroes of the November Uprising on the 50th Anniversary."

There were also greetings from the Lviv City Council, readings of letters and telegrams from abroad, poems recited in honor of the participants, and a performance of the 1830 march.

At 8 p.m. a soiree was held in the City hall, where again toasts were raised "to the veterans and to Poland."

Consequences, interpretations and assessments

The liberal Polish press of the time published materials suggesting that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had been an ideal society. The arguments were as follows: absence of Germanization, democracy, elections, and the separation of church and state. Allegedly, it was where "the free with the free and the equal with the equal" lived in harmony there, where the Orthodox Prince Ostrozkyi felt like a patriot of the common fatherland, and the Cossacks and Haidamaks were the prototype of the radical left wing long before the victory of the French Revolution. In contrast to the Krakow school of history, the nationalists idealized the fact of the uprising and actualized the slogan "For Our Freedom and Yours."

In general, those texts by nationalists that were not censored bordered on the edge of foul play. On the one hand, the authors wrote about a "struggle for independence." On the other hand, however, they did not fight against empires in general, but only against the "colossus of the North." At every opportunity, they described Lviv as a city of freedom, where the Poles enjoyed constitutional rights under the Austrian scepter. And this was true because, thanks to self-government, the Polish liberals, in defiance of Vienna, were able to carry out a larger-scale action than the Ruthenians, who were loyal to the central government.

In the end, due to censorship, most Polish nationalist ideas remained relevant to a limited circle of people in Lviv and Krakow, where the celebrations took place. In other words, an active part of the population of these two cities was mobilized. Among the rural population, where Poland was associated with serfdom and not with heroism and where the clergy supported the conservatives, these events had no impact — unlike the Ruthenian assembly that took place at the same time on the neighboring street.