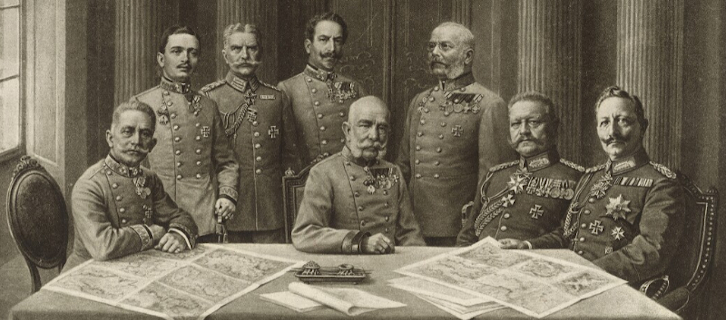

On November 5, 1916, representatives of Austria-Hungary and Germany announced the intention of their monarchs to form the "Kingdom of Poland." Although the future state formation was planned on a very limited territory, seized from Russia, with German control over foreign policy and the army, this news was enthusiastically received by a significant part of the Polish political community. Attempts at criticism and analysis, firstly, were not tolerated by censors, and secondly, were overshadowed by the symbolic meaning of the "proclamation of free Poland."

The Austrians and Germans calculated that in this way it would be possible to attract more Polish volunteers to their side, as well as to mobilize up to one million soldiers from the territory of the future kingdom.

This was a German idea, as the Austrians originally planned to annex the Polish ethnic lands they had captured to Austria-Hungary. Galician Polish politicians hoped that in this way it would be possible to transform the dual monarchy into a union of Austria, Hungary and Poland under the power of the Habsburgs.

In addition, Vienna granted Galicia wide autonomy, refusing the Ukrainian suggestion of dividing the province into Eastern (Ukrainian) and Western (Polish) parts. Consequently, the Polish influence on the affairs of the autonomy with the capital in Lviv increased even more.

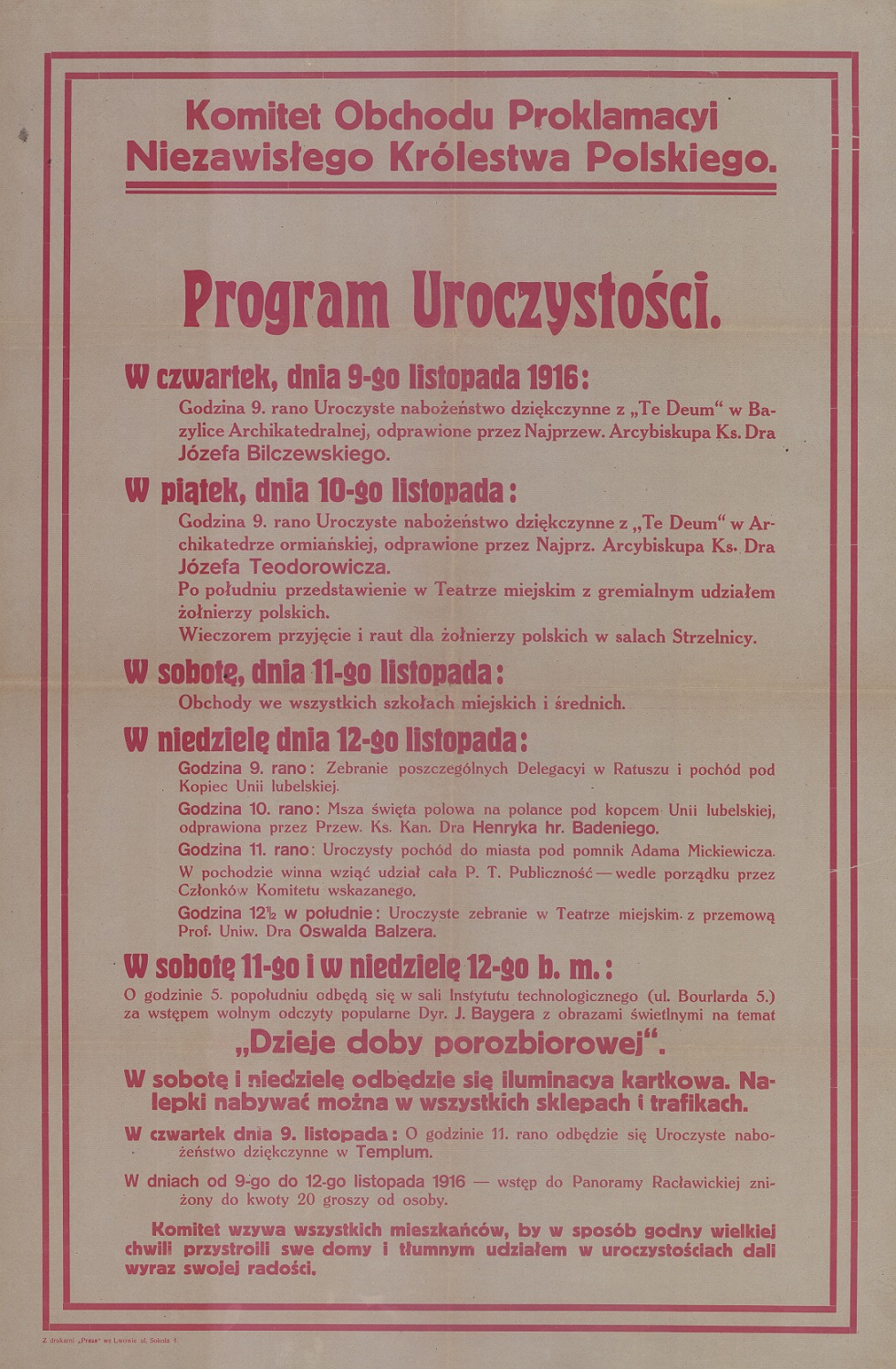

Preparation of a "spontaneous" celebration

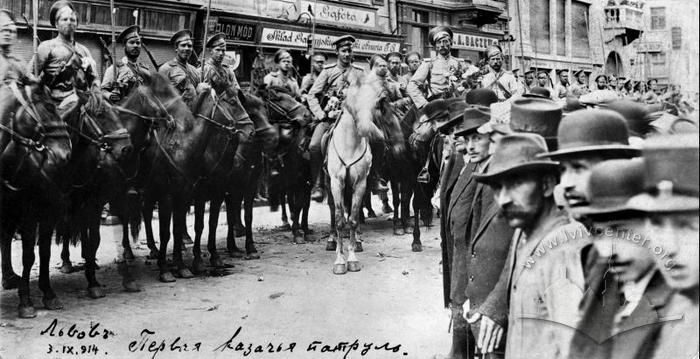

When Lviv learned about the "proclamation of a free Poland" and leaflets with the proclamation were dropped from an airplane at noon, crowds began to gather in the center of the city, mainly near the offices of local newspapers, where the "importance of the moment" was discussed. Some of the buildings were immediately decorated with Polish national flags.

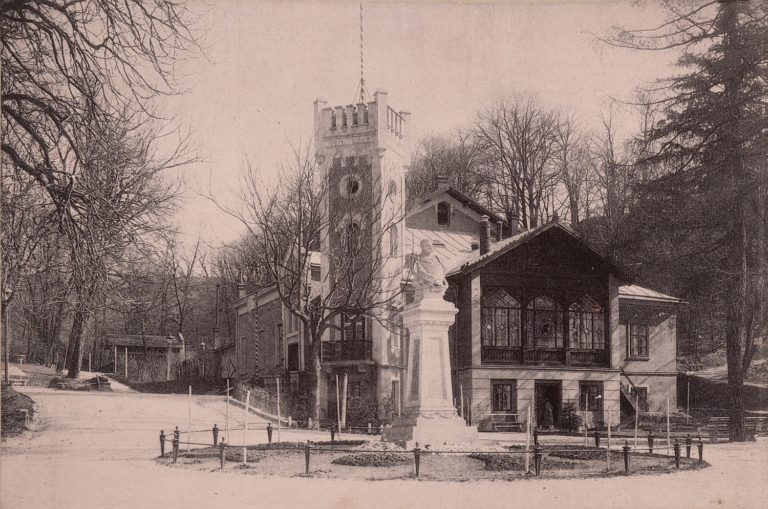

In the evening, a spontaneous rally gathered near the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. There were Polish legionnaires, scouts, schoolchildren, representatives of the Polish Supreme National Committee, and the general public. An orchestra played, young people led a torchlight march of "Lviv children", speeches were delivered in honour of "free Poland." Then, after singing the anthem "Jeszcze Polska nie zginęła", people went to the premises of the Polish Supreme National Committee (an inter-party Polish association oriented towards the Quadruple Alliance) on ul. Batorego (now vul. Kniazia Romana), where patriotic songs were sung again.

On November 6, members of the advisory City Council and of the magistrate as well as other respected citizens gathered in the large assembly room of the city hall: "after a 27-month break, the city's representation gathered." There were many speeches, a decision was taken to send telegrams to the emperor and "to Warsaw". At the same time, however, Lviv representatives of the Supreme National Committee were holding their own meeting, so it is difficult to say in whose hands there was more power at that moment.

Ultimately, it was the Suprene National Committee and the Polish Women's League, and not the magistrate, that were responsible for organizing the celebration in Lviv. They decided to put the main emphasis on the Polish military, their new heroes. This does not mean that there was no local administrative resource. On the contrary, the School Board issued an order recommending that high school students participate in the general demonstration, and before that, students of all grades participate in religious services and activities after them, which were held in schools.

Course of the celebration on November 9-12

Thursday, November 9, began with a thanksgiving service in the Latin Cathedral; accordingly, the shops of "Polish owners" did not work until lunch-time, as in good old days. Some of the celebration participants wore Polish national costumes, kontuszes, which had not been reported on since the time of the Russian occupation. German officers and the German consul were present: a rather unusual situation for Lviv, given the history of Polish protests at the consulate. Also there certainly were legionnaires, guilds, veterans of the January Uprising, representatives of the authorities, etc. Bugle calls were played from the city hall tower, which also happened for the first time after the Russian occupation.

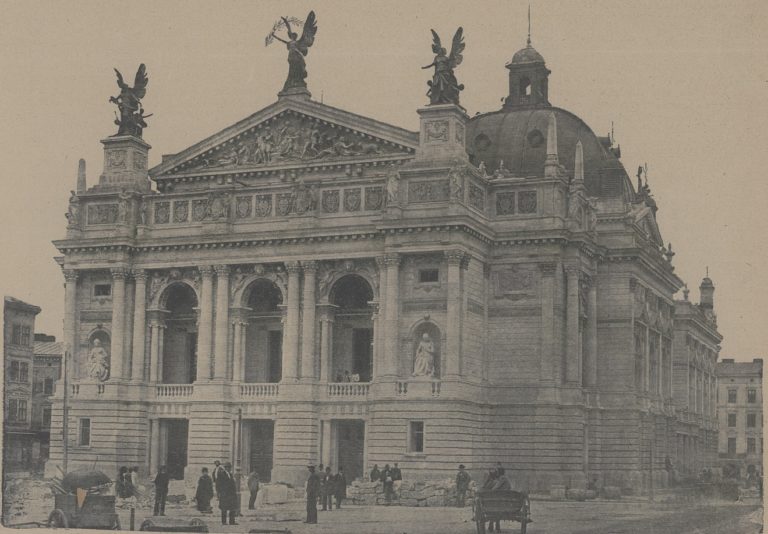

On Friday, November 10, a solemn service was held in the Armenian Cathedral. Then there was a performance at the City Theater and an evening at the Strzelnica (shooting range) for the legionnaires; in general, it was decided to dedicate that day exclusively to the "Polish army." The program was announced in the press, so it is not surprising that the column of soldiers who went from the City Theater to the Strilnytsia was accompanied by crowds of young people. At the Strilnytsia, the soldiers were greeted by rectors, heads of institutions and organizations; of the official representatives of the authorities, however, only starosta Kazimierz Grabowski was present. Similarly, there were no high-ranking Austrian officials in the theater on that day; they came on the following day, when the evening was not devoted purely to "Polish soldiers."

On Saturday, November 11, special "tours" were held in schools of the city; there were also services for students in Roman Catholic churches and synagogues (in particular, in the Tempel).

The culmination of the holiday was Sunday, November 12. After an assembly in the city hall, the procession went to the Union of Lublin mound on the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) Hill, where a field mass was celebrated. Specifically for the service, an altar was built there; bugle calls were played from the mound, while Polish "legionists" acted as a military honour guard. From there, there was another march, this time to the Mickiewicz monument. and then to the City Theater, where another celebration was held. A lot of people gathered there: in addition to the usual associations, educators, guilds and corporations, there were lots of Polish peasants, mostly women and children, since the men were at the frontline.

In general, as the Polish press reported, the day was spent under the motto "Everything through Poland and for Poland", so it was not surprising that the Austrian officers and representatives of the commandant's office ignored the Sunday’s events. There was one more episode that was an indication of fundamental changes: near the Mickiewicz monument, a group of German officers saluted while the Dombrowski March (informal and later the official national anthem of Poland) was performed. It was hard to imagine such a situation in pre-war Lviv.

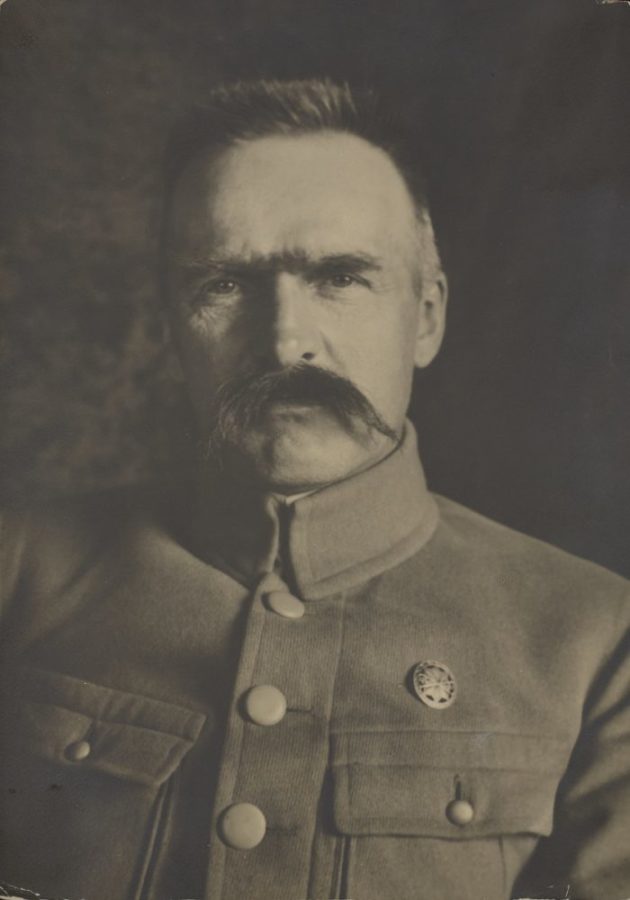

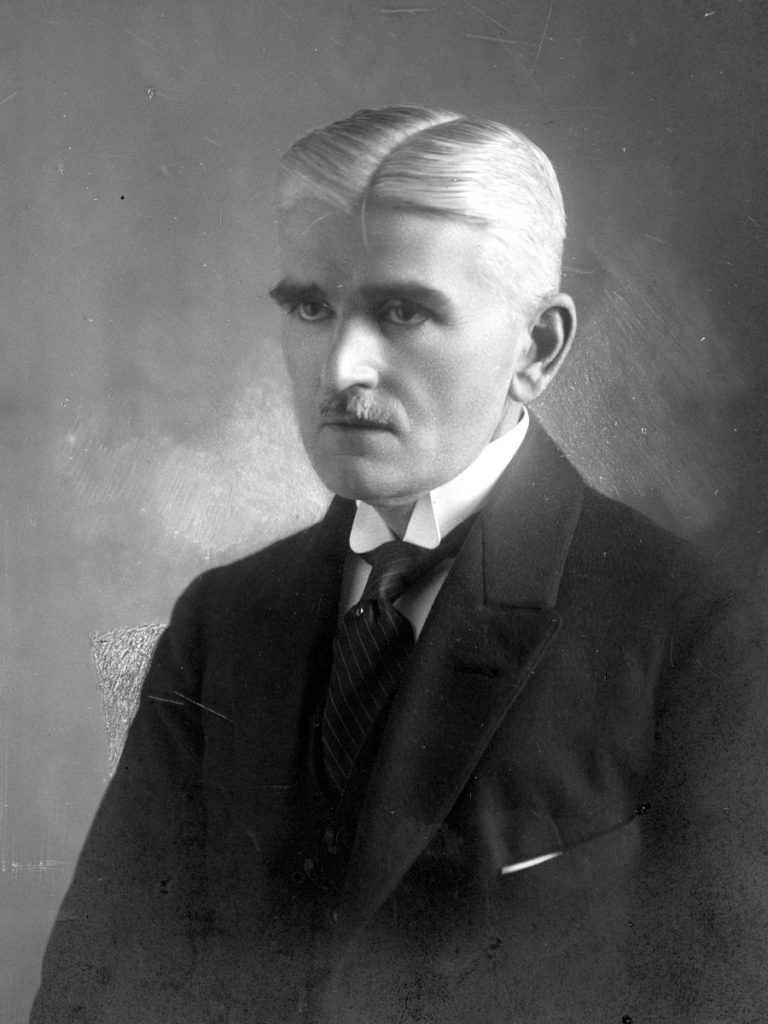

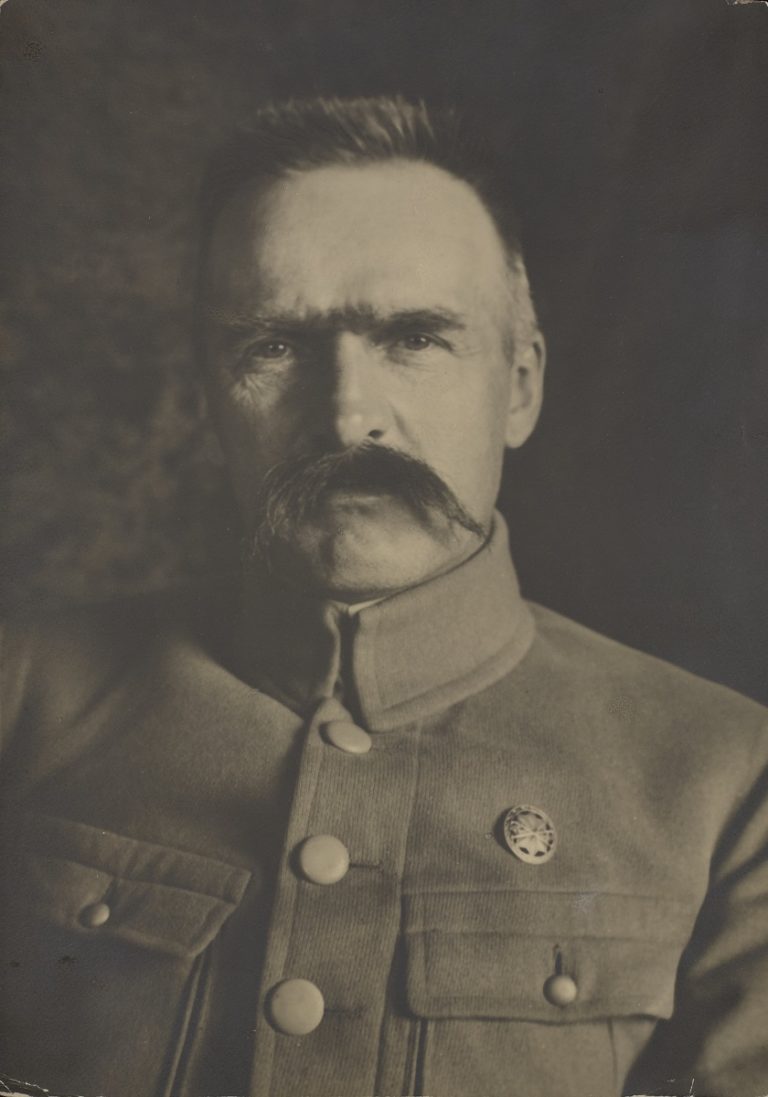

Separately, it is worth paying attention to the decorations that were used in public space. The main subject of the illumination cards was a white eagle, white and red cockades and portraits of Józef Piłsudski becoming very popular as well. As regards flags, Polish national white and red ones dominated totally.

Later, there were many more similar gatherings and meetings, at which Polish and Jewish organizations hurried to express their joy and show their commitment to the "Polish state"; special thanksgiving services were celebrated in churches, and even tickets to the Racławice panorama were sold at a lower price.

It should be understood that the main events took place in Warsaw, which became the capital of the newly proclaimed Kingdom of Poland, while the events in Krakow were at least not inferior to those in Lviv. There were many reports of similar "tours" from various cities of Galicia and lands of the Kingdom of Poland. Thus, Lviv did lose the status of a capital city, at least in what regarded the "Polish cause."

The Ukrainian press was more concerned with general political issues, in particular the status of Galicia after the creation of "free Poland" and the mutual understanding between Vienna and the Polish elites. Mentioning the demonstrations in Lviv, the Ukrainians just reported that they had been held and that many houses had been decorated with Polish and Austrian flags.

* * *

In general, demonstrations in November 1916 showed that mass Polish events could be organized in Lviv in spite of the evacuation and deportations — this time, however, with peasants from nearby villages being involved, which had earlier been considered a purely Ukrainian method of mass politics.

On the other hand, Lviv was losing its status as the main Polish center: the capital of the "freest part of divided Poland." There was more security and therefore more political activists in Krakow. And the main, important and therefore the most massive manifestations took place in Warsaw. It was Warsaw that, after all, was the focus of Polish politicians.