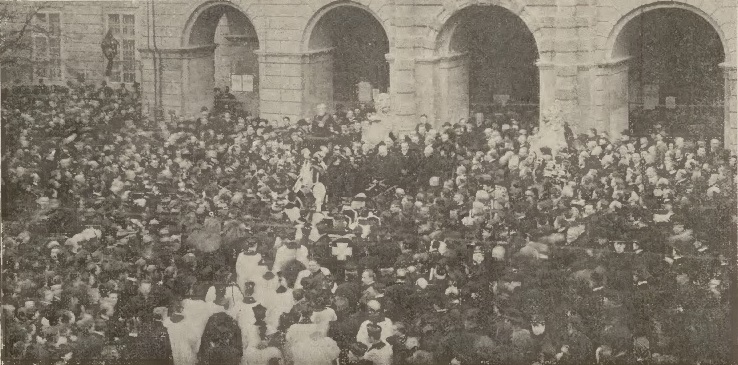

After the unexpected death of the current burgomaster and a popular politician, the city authorities organized a farewell ceremony, which the Polish press of that time described as a "city-wide manifestation." It took place on April 16, 1907.

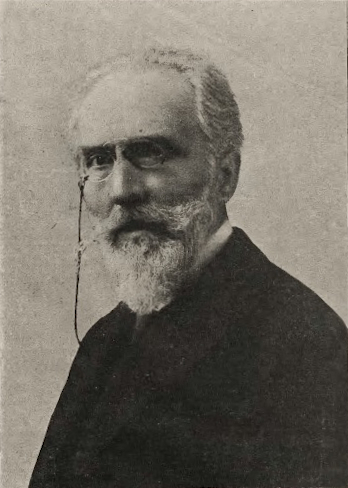

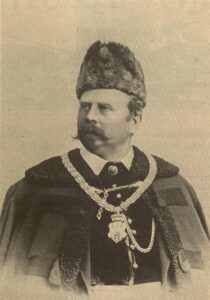

Michał Michalski, wearing Polish national garments, with the ceremonial gold chain of the head of the city

Michał Michalski came from a non-aristocratic Lviv family. After finishing school, he worked in a forge. He took part in the Polish January Uprising of 1863. After returning to Lviv, he started his own business and some time later became the owner of a carriage manufacturing factory. He received the citizenship of Lviv only in 1878, and as early as 1880, at the age of 27, he was elected to the City Council. Apart from working as the second vice president (1889-1895), the vice president (1895-1905), and later the president of Lviv (from 1905), he was also enthusiastically involved in public activities. He was a member of the Sokół, the president of the Rifle Association, a member of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Lviv, the governing bodies of the Count Skarbek Foundation, the Industrial Museum and many other organizations. From 1889, he was also a member of the Galician Diet (Sejm). His energetic political and public activity coincided with a period when Lviv was turning into the "capital of the Polish movement." Accordingly, Michał Michalski himself became a politician of national scale.

In addition, in the late 19th century, the entire political class of Austria-Hungary was democratized, when non-aristocrats started occupying high positions in the government. The president of Lviv, Michał Michalski, was the embodiment of these changes, the personification of a new type of politician. A man "from the people" who "made himself" and was a representative of "ordinary citizens" of the city.

Probably, these factors, as well as the fact that the actual president of the city was being buried, turned his funeral ceremony into a city-wide manifestation. In previous years, only the burial of a prominent church hierarch could reach such a scale.

After the burgomaster's death

Seven hours after the unexpected death of the city president, Michał Michalski, on Saturday, April 13, at 18:00, a special meeting of the City Council members present in Lviv took place. The meeting room was decorated accordingly: the desk of the deceased was covered with a black tablecloth, with the burgomaster's ceremonial gold chain placed on it. The galleries of the hall were open to the public.

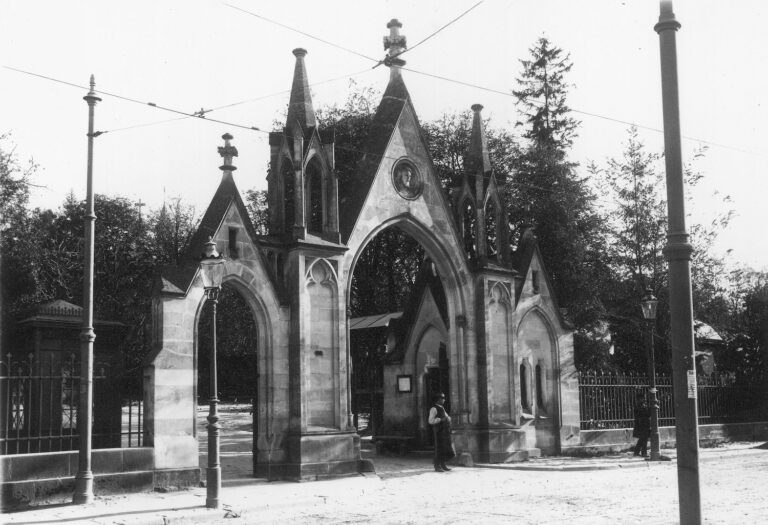

The Council decided to hold a funeral and arrange a grave at the expense of the city, to place mourning ribbons on the houses, to reduce school hours and to cancel theatrical performances. Along the route of the mourning procession on the day of the burial (from the City Hall through the square in front of the Latin Cathedral, Mariacki Square, Halicki Square, Bernardyński Square, Piekarska Street to the Lychakivsky Cemetery), street lamps covered with black cloth were to be lit. In addition, the vice president of the city, Tadeusz Rutowski, was instructed to deliver a speech at the grave of the deceased. Individual members of the Council were delegated to express their condolences to the widow. Like her husband, Michalina Michalska, née Krykiewicz, paid a lot of attention to charity. There were also plans to establish a charity fund named after the deceased.

- Міхаліна Міхальська/Michalina Michalska

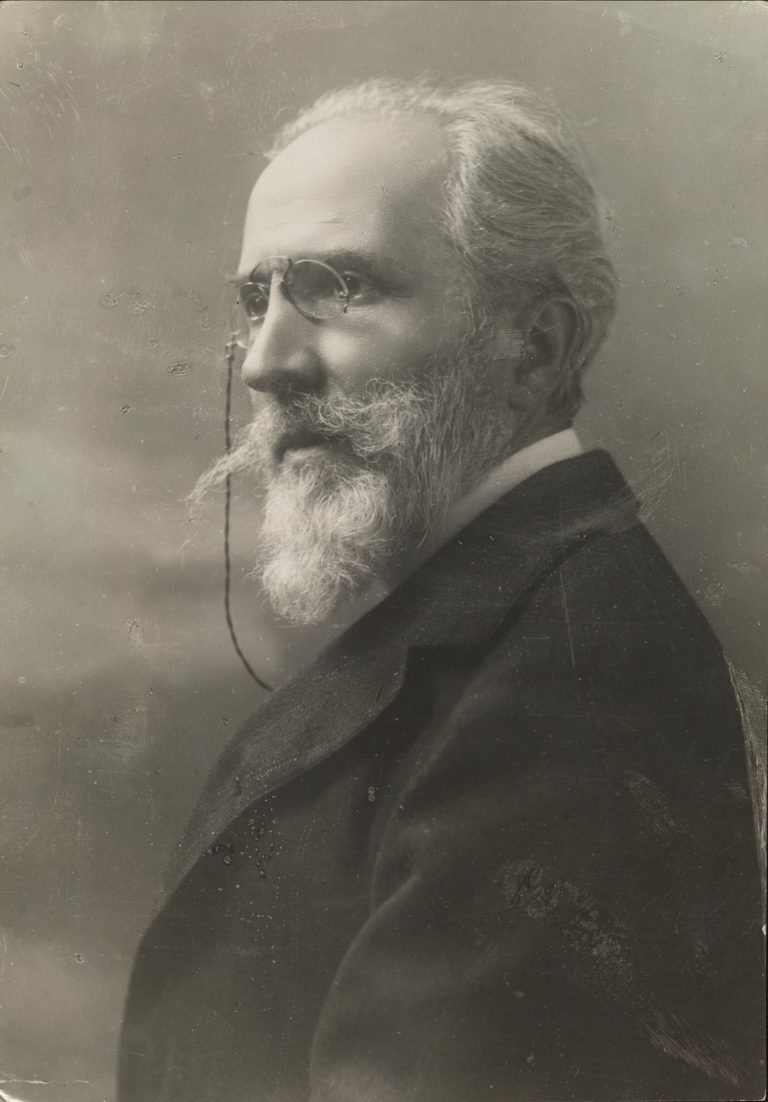

- Tadeusz Rutowski, the vice president of Lviv and likely successor of Michalski/Тадеуш Рутовський, віце-президент Львова та ймовірний наступник Міхальського

The organizing committee, headed by Tadeusz Rutowski, decided to involve school students (from year IV and older) in the burial ceremony and to hold memorial services in schools on Monday. A list of all institutions, associations and organizations was drawn up, which, according to the specified order, had to form a procession to move from the City Hall to the Lychakivsky cemetery, as well as the list of those who would give speeches over the coffin. It was decided to post announcements about the funeral scheduled for Tuesday, April 16 at 15:00 all over Lviv.

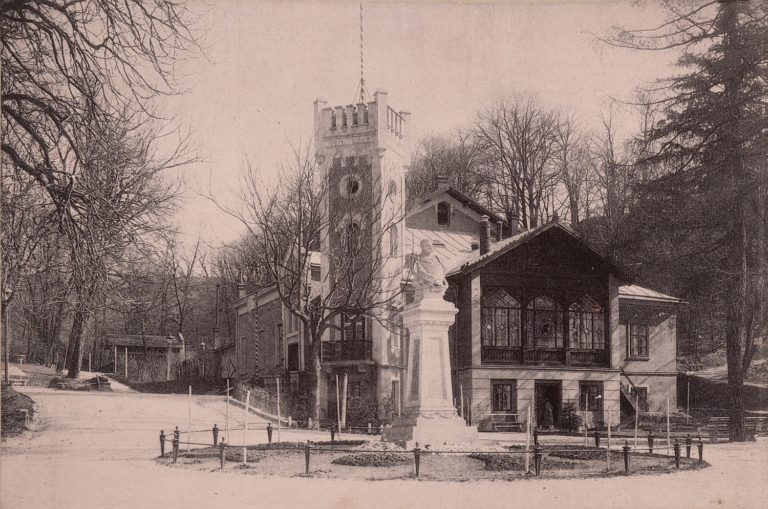

Similarly, numerous Lviv associations (Michał Michalski was a member of many of them) decided to join the farewell ceremony and to honour his memory. For example, the Rifle Association, in addition to participating in the funeral in full, decided to cancel all their events for the three following weeks and to install his bust on the territory of the Strzelnica (Shooting Range). The Teachers' Association decided to create a scholarship fund for the education of Lviv orphans.

From April 14 to 16, the body was laid out in a black coffin for farewell in the large hall of the City Hall, which, besides a cross, flowers and candles, was decorated with a copy of Our Lady of Częstochowa icon, one of the main Polish sacred objects.

The body of Michał Michalski in the coffin. The icon of Our Lady of Częstochowa (a copy) is placed behind

There were so many people who wanted to pay their last respects to the deceased that it was difficult to keep order. Therefore, later certain hours were established when it was possible to enter the premises.

Funeral

On Tuesday, April 16, 1907, at noon, all workshops and factories stopped working so that the workers and craftsmen of Lviv could bid their farewells to the body of the city president. Shops were closed at 2 p.m. Offices and government institutions also were closed earlier than usual. From the City Hall to the gate of the cemetery, tens of thousands of Lviv residents gathered to see Michał Michalski on his last journey. The City Hall tower was decorated with mourning flags.

At 15:00, a mourning service began in the City Hall, held by priests of the Greek Catholic, Roman Catholic, and Armenian Catholic rites (namely, the father-mitrate of the Greek Catholic Church Andriy Biletsky, the Armenian Archbishop Józef Teodorowicz and the Roman Catholic Archbishop Józef Bilczewski). After that, to the accompaniment of 24 strikes of the City Hall bells, the body of the "first citizen" was taken to the hearse.

In front of the City Hall, the combined choir of the Liutnia and Ekho societies performed a mourning song. Tadeusz Rutowski, the vice president of the city, spoke from a platform covered with cloth in mourning colours and the colours of the city. When his speech was over, a signal was given to the head of the column with special whistles, and the procession started.

The problem was that a lot of space was needed to line up all the societies, organizations and institutions participating in the funeral in the planned order. Based on their list, one can get an idea of the social structure of Lviv in the early 20th century. There were professional and patriotic organizations, corporations, deputies and officials, clergy.

The march was led by firefighters and military veterans with an orchestra followed by children (schoolchildren and pupils of orphanages). Separately, the workers of Michał Michalski's factory were going. There were gymnasium students, representatives of the Polytechnic and Ossolineum. There were the Home for the Poor, the Orphanage, the Deaf and Dumb Institution, the St. Helena Institution, the Jewish Orphans Institution, the Stanisław Kostka Institution; members of the Sokół, some of them on horses; as well as the Kiliński Society (with white and red ribbons), the Jedność, the Gwiazda, the Skała, the Zgoda, the Kościuszko Society, the Yad Charuzim, the Association of Jewish merchants, evangelists, the associations of cobblers, clerk assistants, teachers, craftsmen. There were representatives of the following corporations (some with standards, most with wreaths): blacksmiths and cart-wrights, butchers and soap makers, builders, theater artists, journalists, lawyers, notaries and many others. Among them, the Society of the 1863 Uprising Participants and the Rifle Association stood out. Among the clergy were rabbis, many Roman Catholic monks, and few Greek Catholic clergymen.

In the middle of the column, closer to the widow and the hearse, there were members of the magistrate, the City Council and the Sejm, deputations from different cities and towns of Galicia, members of the Provincial Department led by the Marshal of the Sejm Stanisław Badeni, employees of the governor’s office, and the governor, Count Andrzej Potocki, himself.

Such a massive character of the event cannot be explained only by the fact that the current burgomaster was being buried. Probably, it was influenced by the growing role of local self-government (development of schooling, care of the needy, etc.), as well as the very figure of President Michał Michalski as a patriot and national politician.

In the middle of this mass of people (which stretched from the Rynok Square to Piekarska Street), two horse-drawn hearses were moving. The hearse of the city president was pulled by three pairs of horses. On another, wreaths from the governor, from the marshal, from the Krakow City Council, from family and friends, as well as from the Lviv magistrate (decorated "in the colours of the city") were carried.

On the way, the procession made two planned stops: near the monument to Adam Mickiewicz, where the Academic Choir performed a mourning song, and on Bernardyński Square, where the city orchestra performed one of Chopin's compositions. At that time, the police, firefighters and the local customs service were monitoring the order.

From the gate of the Lychakivsky cemetery to the burial place, members of the Rifle Association and employees of the magistrate carried the coffin in their arms. The burial ceremony was conducted jointly by Greek and Roman Catholic priests. After that, the planned speeches were delivered.

The second vice president of the city of Lviv, Stanisław Ciuchciński, spoke on behalf of "all the townspeople and members of the Rifle Association" about the work of the deceased for the benefit of "the Fatherland and the City." A representative of the Society of the 1863 Uprising Veterans spoke about the "Polish soldier" Michał Michalski. Other speeches, given by a priest and representatives of the magistrate, the chamber of commerce and the chamber of craftsmen, were more politically moderate. These topics clearly indicate a shift in emphasis from the local or imperial to the national and social.

The ceremony ended around 18:00.

Interpretation

The texts of the Polish press about the president of the city, Michał Michalski, published in those days, demonstrate the changes in national and social politics in Lviv of the early 20th century, as well as the growing role (including that symbolic) of local self-government.

The late burgomaster, the newspapers reported, "had been at the head of a powerful bourgeois party." He entered politics in 1880, when the elections to the Lviv City Council changed the local political landscape completely. Then the victory was won by the Unity and Consent group of the Roman Catholic priest Stanisław Stojałowski, which included 27-year-old Michał Michalski, while only eight of the former deputies were re-elected.

His very biography, when published in the press, testified to the de-aristocratization of politics. A democrat and liberal, although of noble origin, he did not shy away from work in the forge and did not believe that any, even hard but honest work could be disgraceful. A participant in the revolution of 1863, an entrepreneur, he became the head of the city not by birthright but thanks to his personal qualities and was then involved in the transformation of Lviv into a "true capital."

However, the purpose of this non-aristocratic activities as the head of the city was still reduced to the national issue. After all, as the first vice president, Tadeusz Rutowski, said in his speech, he "spent his whole life correcting the mistakes of the past, in order to return Lviv to Poland." His work was crowned with the "revival of the bourgeoisie for the service of the people."

It is worth noting the place of the Ukrainians in this situation. Firstly, they were not represented at the funeral either numerically or at the highest level (including the clergy). Even obituaries and notes in the Ukrainian press illustrate the growing Ukrainian-Polish confrontation. While the Russophile newspaper Halichanin reported at least that a prominent politician, not an enemy of the Ruthenians and the Ruthenian Church, had died, and the Christian-social newspaper Ruslan mentioned several dates from his life, the populist periodical Dilo published a notice of Michał Michalski’s death under "minor news."