Funerals with the participation of a large number of people took place in Lviv even at the time of strict centralization after the suppression of the Spring of Nations in 1848. These were opportunities to hold legal demonstrations at a time when all mass events, except imperial and religious ones, were prohibited. This type of manifestation did not lose its relevance after the liberalization and granting of autonomy in the 1870s.

Like other church rituals, over time funerals in Habsburg Lviv increasingly acquired a distinctly national character, no less than "classical national" festivities like Epiphany or Corpus Christi. In them, it is important to see not only a massive character, a certain route or the involvement of representatives of the authorities but also the treatment and interpretations accompanying the actions.

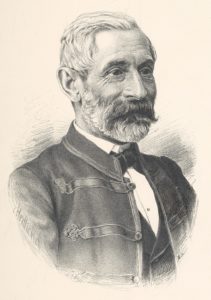

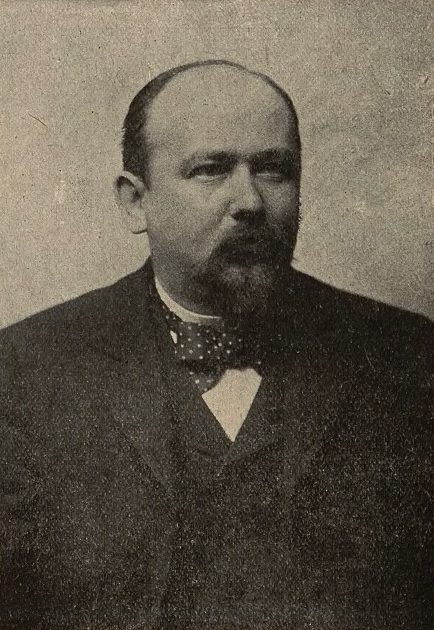

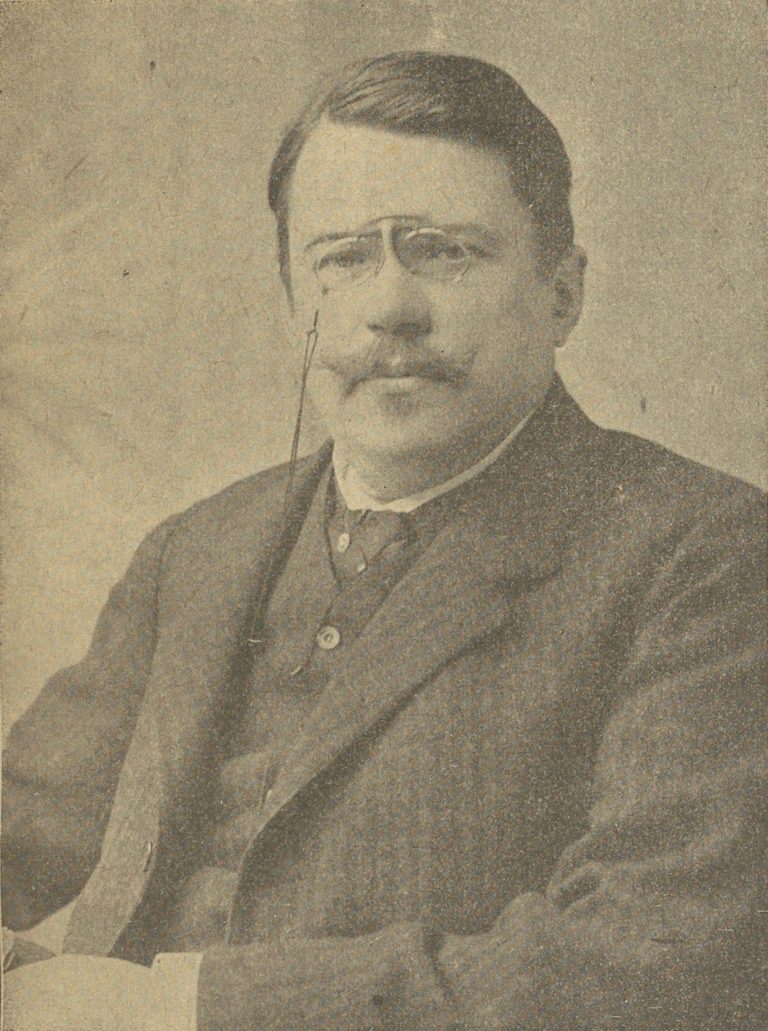

For instance, when the president of the city, Michał Michalski, was buried in 1907, it was a question of a new type of local politician: an entrepreneur (industrialist) of a new generation who had achieved success due to his abilities and not his origin. At the same time, Michalski's role in the all-Polish national project was discussed, as well as Lviv as the center of Polish patriotism. Franciszek Smolka was honoured as a purely national Polish political leader.

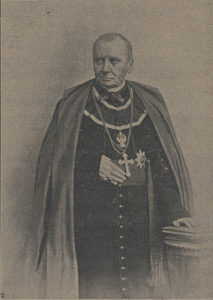

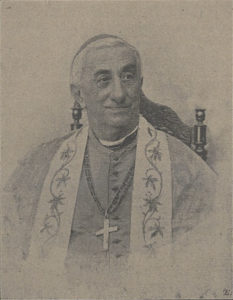

Funerals of Catholic hierarchs

In the second half of the 19th century in Galicia, religious affiliation almost always determined national identity. So Roman Catholic hierarchs were considered "Polish" national leaders, while Greek Catholic hierarchs were "Ruthenian/Ukrainian" national leaders. This was especially true of the Ukrainians, since these hierarchs, at least initially, were almost the only representatives of the "people." The same applied to the archbishops of the Armenian Church, who took an active part in the Polish national project. Thus, funerals of archbishops turned into national demonstrations, where the mobilization of their supporters enabled raising the prestige of the denomination, that is, of the people.

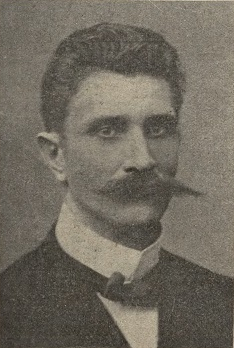

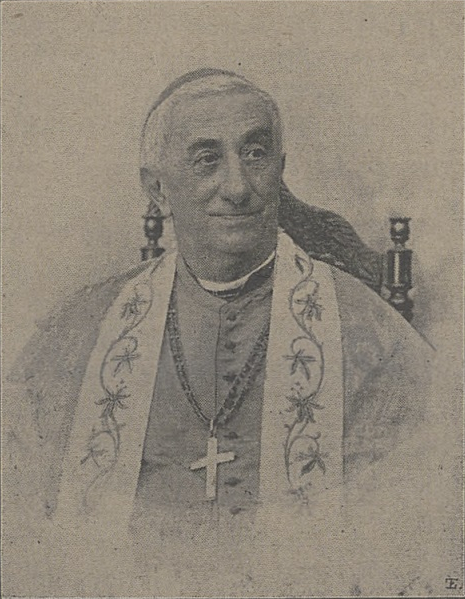

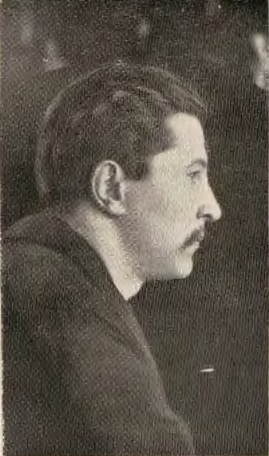

- Сильвестр Сембратович/Sylvestr Sembratovych

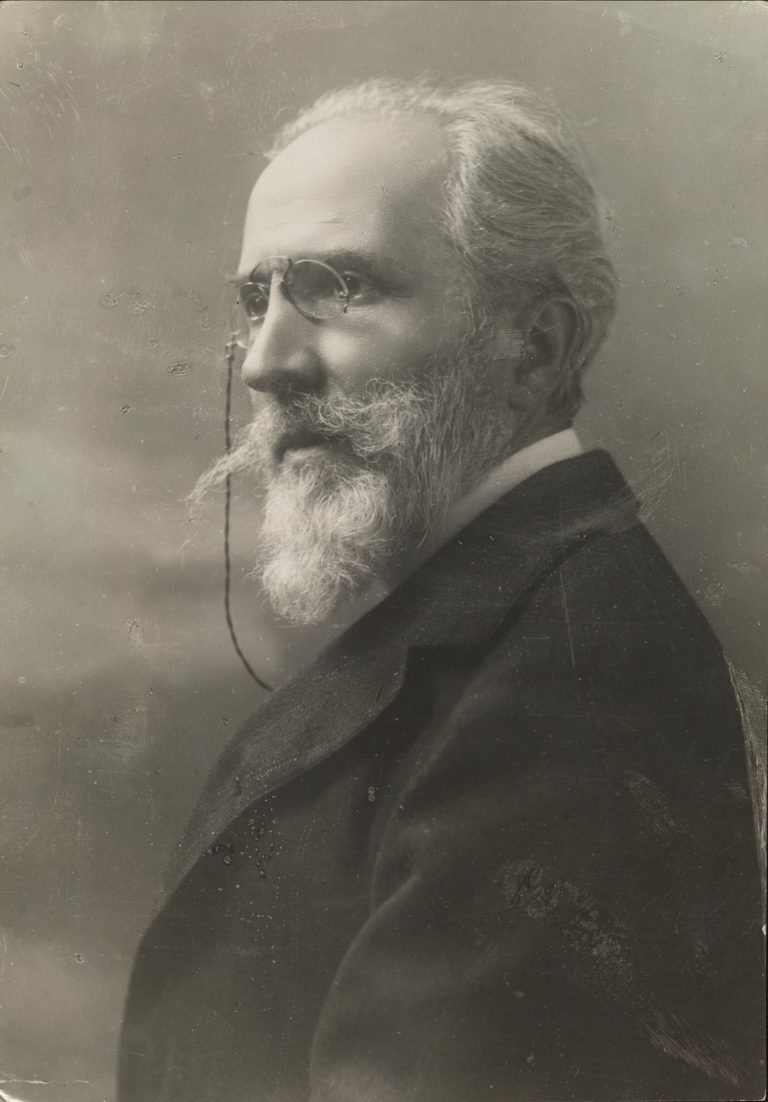

- Северин Моравський/Seweryn Morawski

- Юліан Сас-Куїловський/Yulian Sas-Kuilovskyi

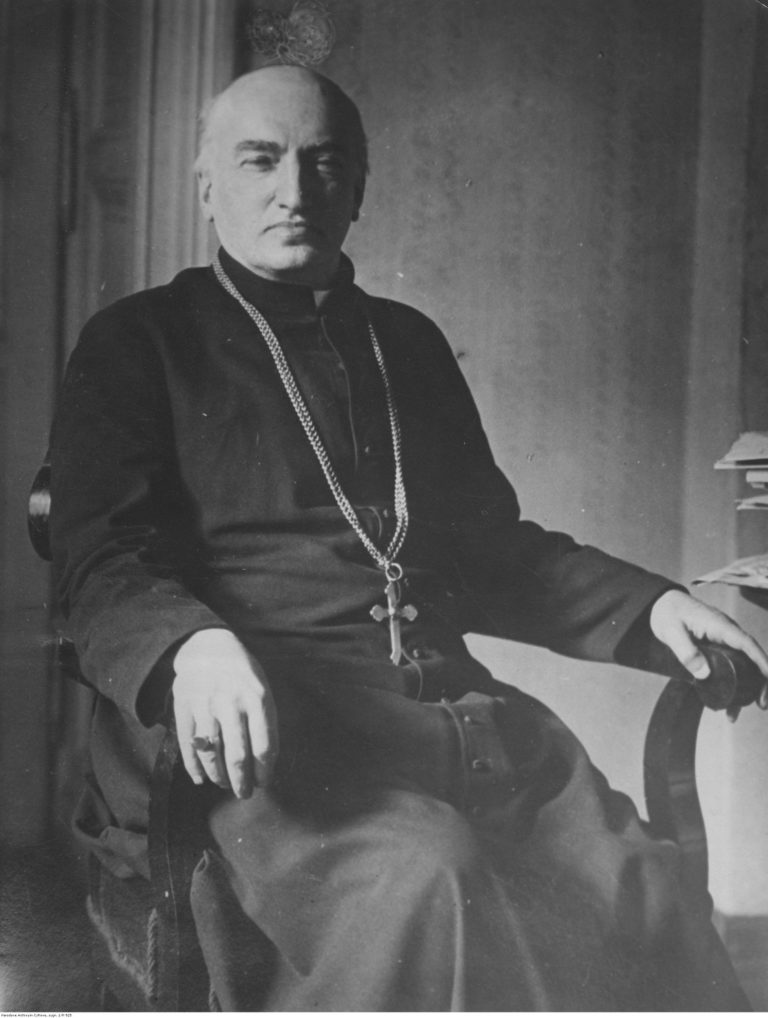

- Ісаак-Миколай Ісакович/Izaak Mikołaj Isakowicz

On August 7, 1898, Greek Catholic Metropolitan Sylvester Sembratovych was buried in Lviv; on May 7, 1900, Roman Catholic Archbishop Seweryn Morawski and Greek Catholic Metropolitan Yulian Kuilovsky were buried; in May 1901, there was a funeral of Armenian Archbishop Izaak Isakowicz. In all these cases, the unity and solidarity of the Catholic clergy of the three rites was demonstrated: funeral services were each time celebrated by priests of all denominations, and representatives of all churches took part in the funeral processions.

Representatives of the authorities acted similarly. Both the governor's office and the City Council were in that or another way present. However, there was still a noticeable difference between the way the "full City Council" bade their farewells to the Roman Catholic hierarch and the way "the City Council representatives" were delegated to the Greek Catholic Cathedral of St. George.

Despite the high social status (next to the hierarchs' remains, their orders and decorations were placed), as well as the role of each of them, above all, as the head of a church, each of the archbishops was a political figure, and therefore caused sympathy or antipathy of an active part of society. This also affected the course of the funeral.

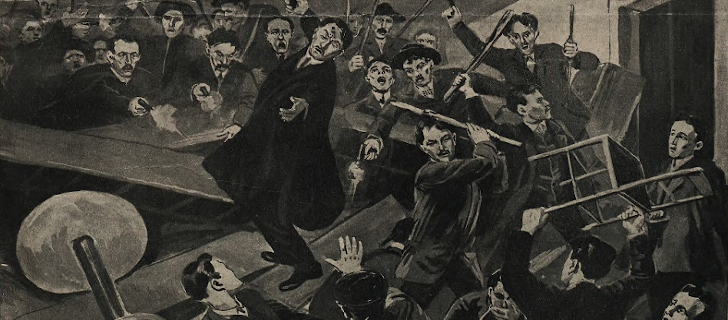

Thus, at the funeral of Sylvester Sembratovych, a cardinal and metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church and a supporter of the New Era policy and a mutual understanding with the Poles, who had hostile relations with Ukrainian populists and Russophiles, there was misunderstanding with representatives of populist organizations. The latter wanted to occupy certain seats, so the police intervened. Even before that, there were disputes about wreaths, which associations wanted to lay, apparently with inscriptions telling from whom they were, while the deceased himself had asked not to do this in his will. So the associations had to be convinced to give the money they wanted to spend on wreaths to charity. In general, Sylvester Sembratovych's will provided for a modest funeral. The cardinal's property was to be distributed mainly for charity: between the workers' boarding school, Basilian monasteries, various aid institutions, widows, orphans; a smaller part was bequeathed to the deceased's sister, her children and distant family, as well as to two personal servants. On the other hand, Sylvester Sembratovych was a cardinal and used a carriage drawn by three pairs of horses. The carriage was used at the funeral, emphasizing the high status of the metropolitan, as well as a silver wreath from the governor's office, but the coffin with the body was carried by priests, in fulfilment of the deceased's will.

The Order of the Iron Crown (1st class) was carried next to the coffin of the Roman Catholic Archbishop Seweryn Morawski. Next to the coffin of the Greek Catholic Metropolitan Yulian Kuilovskyi, who was also unpopular among Ukrainian politicians, there was only one wreath with an inscription reading "The village of Ruske — to their benefactor", as Metropolitan Kuilovsky had been the parish priest of that village for a long time. On the hearse of the Armenian Archbishop Izaak Isakowicz, in addition to his orders and coat of arms, there were wreaths from the Polish Parliamentary Circle, the Ossolineum, and the Armenian Scientific Institute. In his farewell speech, the successor of Isakowicz, Józef Teodorowicz, spoke of the deceased as of "the most popular citizen of the province", although the latter was "neither a landowner, nor a politician, nor a knight, but a poor and quiet priest."

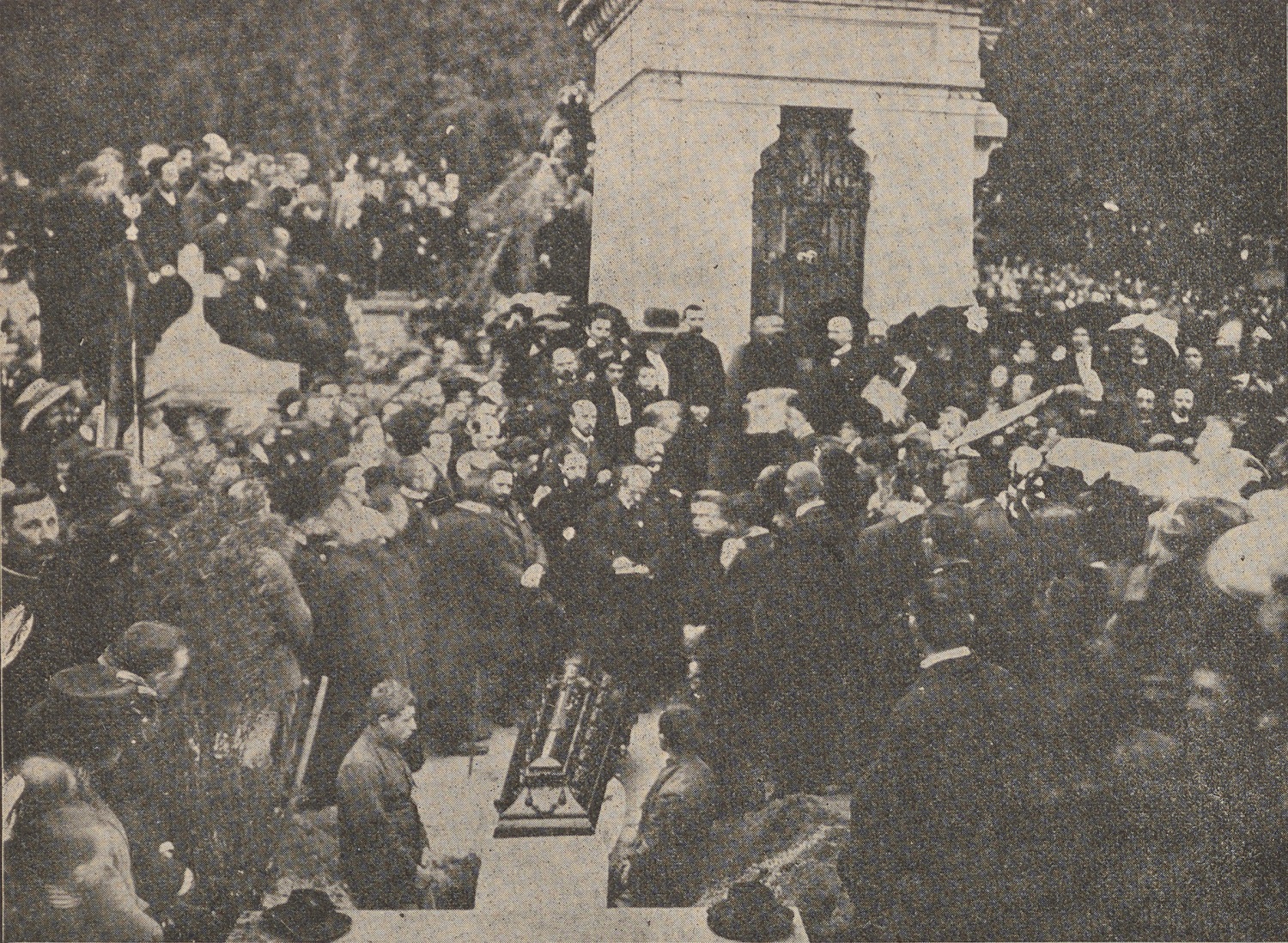

Along with the attributes, the presence of political activists, the elite, and the local population at the funerals obviously had a huge significance. Governors of the province, marshals of the Diet (Sejm), presidents of the city of Lviv and bishops were always present. However, there were also noteworthy differences. Parish priests from all over the province, leading groups of their parishioners, gathered for the funerals of Greek Catholic metropolitans. Therefore, most of the participants in "Ukrainian" funeral processions were peasants, while the "Polish" hierarchs were escorted on their last journey mainly by the townspeople, residents of Lviv.

In general, solemn marches were usually led by pupils of schools or orphanages, followed by monks, church brotherhoods, associations and organizations with their standards (it was here that national features were clearly visible), representatives of the University and the Polytechnic. In addition to the police, order was guaranteed by an honour guard formed by the military. The hearse was followed by the deceased’s family and representatives of the authorities, as well as the high military command.

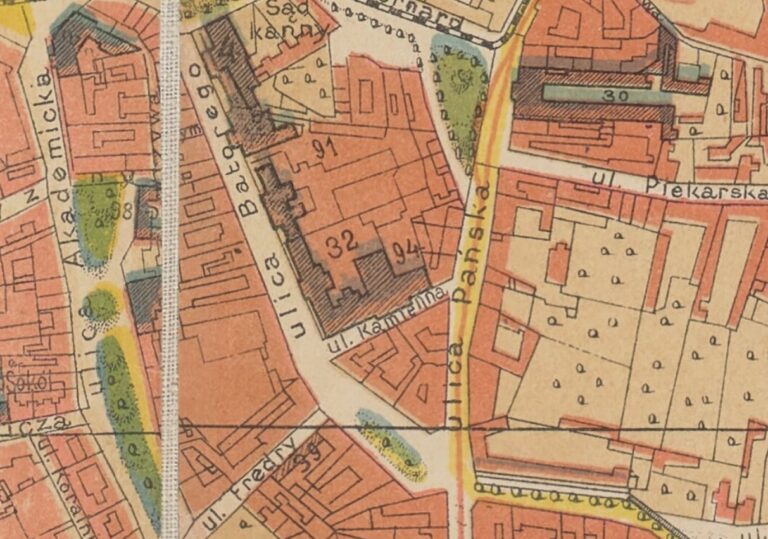

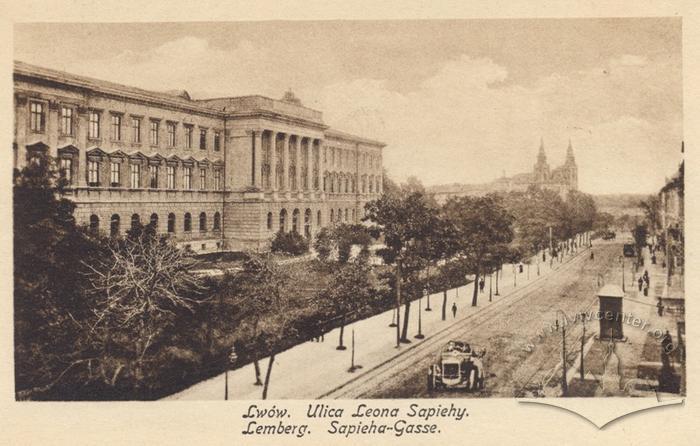

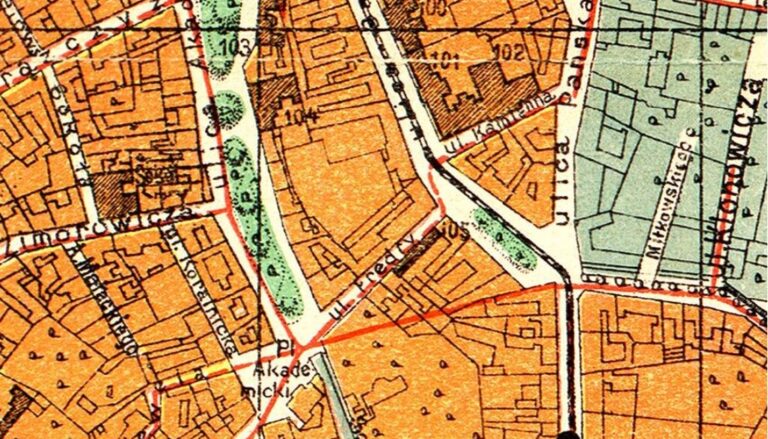

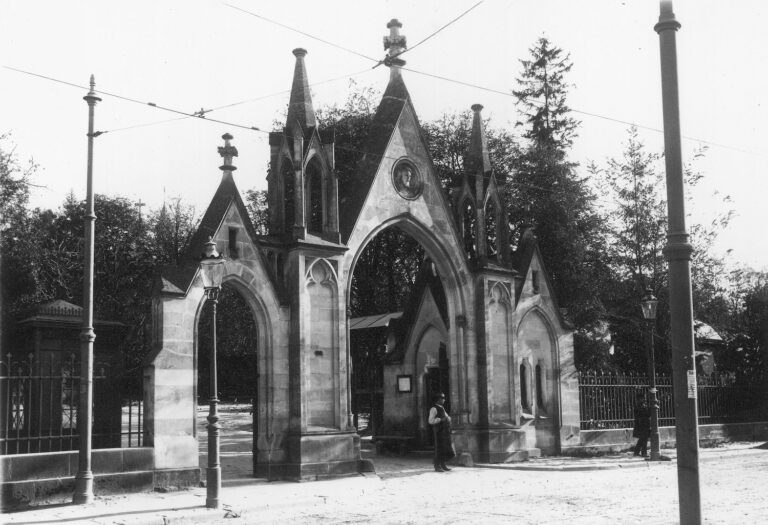

There was no established place for the funerals of the highest church hierarchs. Accordingly, on the map of the city, these events were reflected differently each time. Mourning flags and mourning bells in churches or cathedrals were common. The procession at the funeral of Sylvester Sembratovych followed this route: St. George's Cathedral — Greek Catholic Theological Seminary — St. George's Cathedral. To enable doing this, traffic was blocked on Mickiewicza Street, Jagiełłońska Street, Karola Ludwika Street, Kopernika Street, Leona Sapiehi Street, Lipowa Street; tram traffic was also restricted.

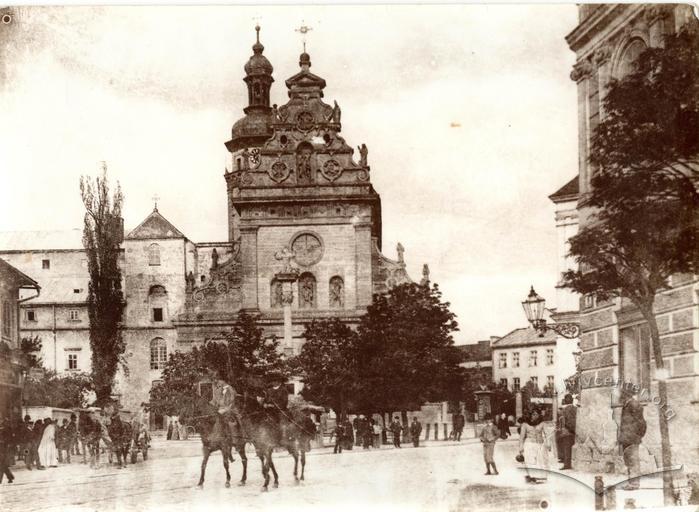

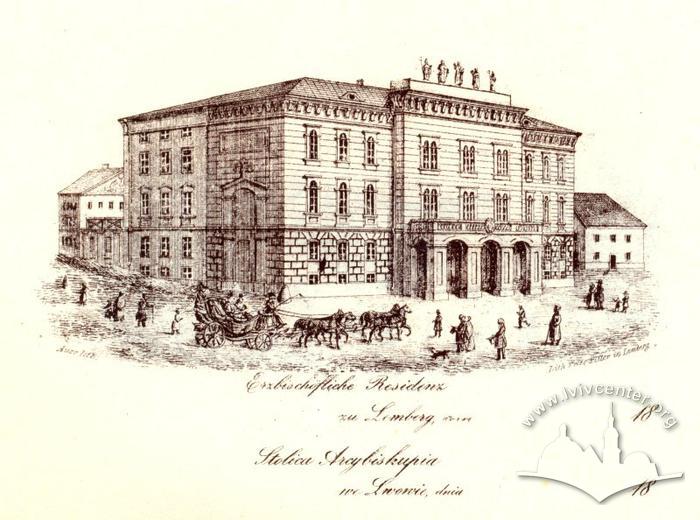

The body of Seweryn Morawski was carried from the archbishop’s palace to the Latin Cathedral, along Czarneckiego Street, Ruska Street, Rynek Square and Kapitulna Street. From there to the crypt in the church of the Roman Catholic seminary, the procession moved through Halicki Square, Mariacki Square, Bernardyński Square and Czarneckiego Street.

Yulian Kuilovsky and Izaak Isakowicz were buried at the Lychakivsky cemetery, the routes running, respectively, from the Armenian Cathedral and St. George's Cathedral through the city's center (Mariacki Square) and Piekarska Street.

Apart from the "visible" marks, clear from the description of the ceremonies, national differences were also mentioned in the press of those times. For example, the newspaper "Dilo" noted that announcements about the death of Seweryn Morawski were printed only in Polish, while those of Yulian Kuilovsky were only in Ukrainian. The "Kurjer Lwowski" called Metropolitan Kuilovsky the leader of the entire "Ruthenian people and the first citizen"; that was why his body was carried to the cemetery by peasants.

At Izaak Isakowicz's funeral, in addition to the usual list of associations and organizations, society was also represented by members of the paramilitary Sokół and a group of participants in the 1863 Uprising. Speeches about his "work for the good of Poland and the nation" were given over the grave.

Funerals of the Polish secular elite representatives

The funerals of the secular elite during the period of autonomy also vividly illustrated the changes affecting the city and the perception of the city at that time.

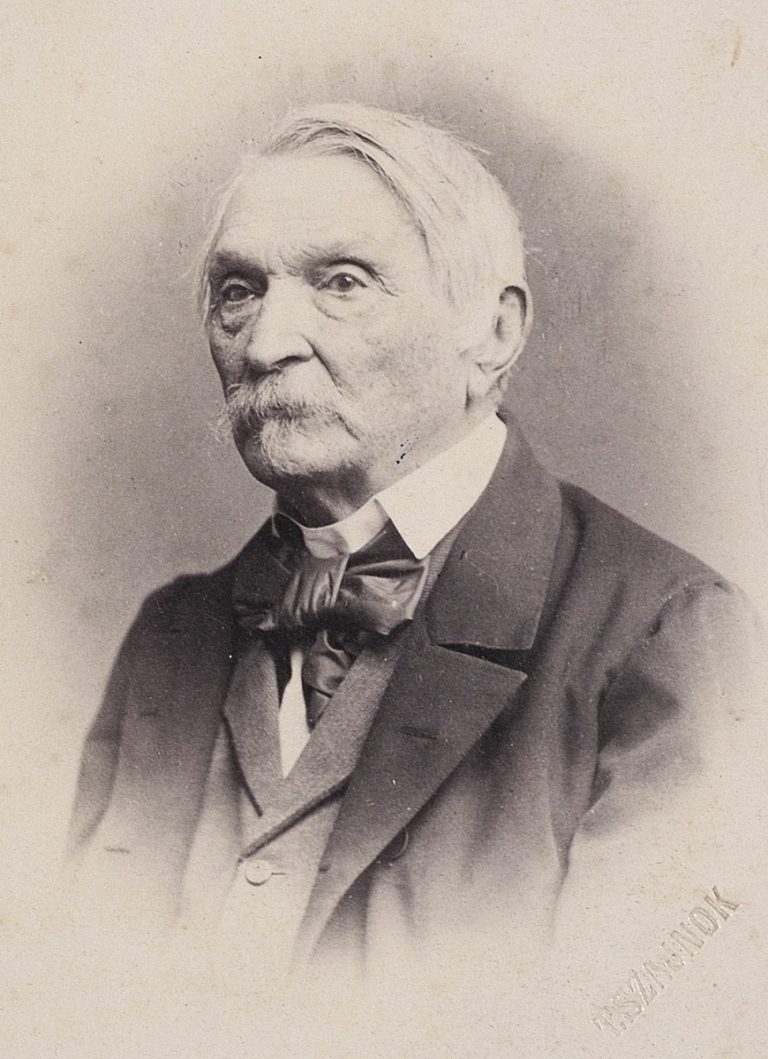

When the outstanding Polish writer Aleksander Fredro was buried on July 18, 1876, the area around his palace and up to the Roman Catholic church of St. Nicholas was full of people: youth, schoolchildren, members of associations, "comrades in arms" (the deceased participated in the November Uprising). The funeral procession left the church through Halicki Square, Mariacki Square, Kopernika Street and Nowy Świat Street to the Gródecka (Horodotska) turnpike. There, the townspeople bade their farewells to the body, which was then taken to the family tomb in the town of Rudky.

Funeral procession at the beginning of modern Hrushevskoho and Drahomanova Streets. A drawing based on a photograph by Józef Eder, 1876

Over time, the formation of a pantheon at the Lychakivsky cemetery became more important, so efforts were made not to bury prominent citizens in their family estates, but on the contrary, to specially bring their bodies to Lviv.

For example, in November 1905, the farewell ceremony for the participant of the January Uprising, the "colonel of the Polish army" Jan Rudowski, was held in Lviv. He was buried next to other insurgents for whom a separate field was allocated at the Lychakivsky cemetery. The National Chapel (choir) and veterans of the January Uprising led the procession from the railway station along Kolejowa Street, Sapiehi Street, Kopernika Street, Mariacki Square, Bernardyński Square, and then along Piekarska Street to the Lychakivsky cemetery.

The funeral of the president of Lviv, Wacław Dąbrowski, in 1887 showed both the city's patriotism, the high status of the deceased, and the new important role of local self-government, which also became "power." The Catholic clergy of three rites were invited to the ceremony, performances in theaters were cancelled, shops were closed. The traditional Saturday bazaar on the Rynok Square was also cancelled. The funeral itself was held at the expense of the city, and the farewells to the body were bidden in the City Hall. Houses in the city center were decorated with mourning flags.

On Saturday, April 2, at 10:00, the body was taken to the Rynok Square. Mourning bells were rung in the churches and cathedrals of the city, the vice president of the city of Lviv, Feliks Gryziecki, spoke from a special platform. The coffin was carried by eight city councilors in "mourning national costumes" around the Rynok Square, then along Trybunalska Street and Teatralna Street to the Latin Cathedral.

The list of participants in the funeral showed how important the position of the head of the city of Lviv was during the period of autonomy. There were representatives of the governor's office and of the Diet (Sejm), as well as the high military command. From Krakow, the president of the city, Feliks Szlachtowski, and Cardinal Jan Puzyna arrived. The procession also included pupils of orphanages, members of church fraternities, associations and organizations, schoolchildren, the Sokół members, workers; in total, as the press reported, several thousand people. More than fifty wreaths alone were carried. The musical programme was provided by the choirs of the Liutnia society, the Harmonia society and the choir of the Greek Catholic seminary.

The procession passed from the Latin Cathedral through Mariacki Square, Halicki Square, Bernardyński Square and Piekarska Street. The hearse, as "a manifestation of the deceased's modesty", was pulled by only one pair of horses. During the march, order was guaranteed by city officials, since volunteer firefighters, veterans and the Sokół members took part in the procession.

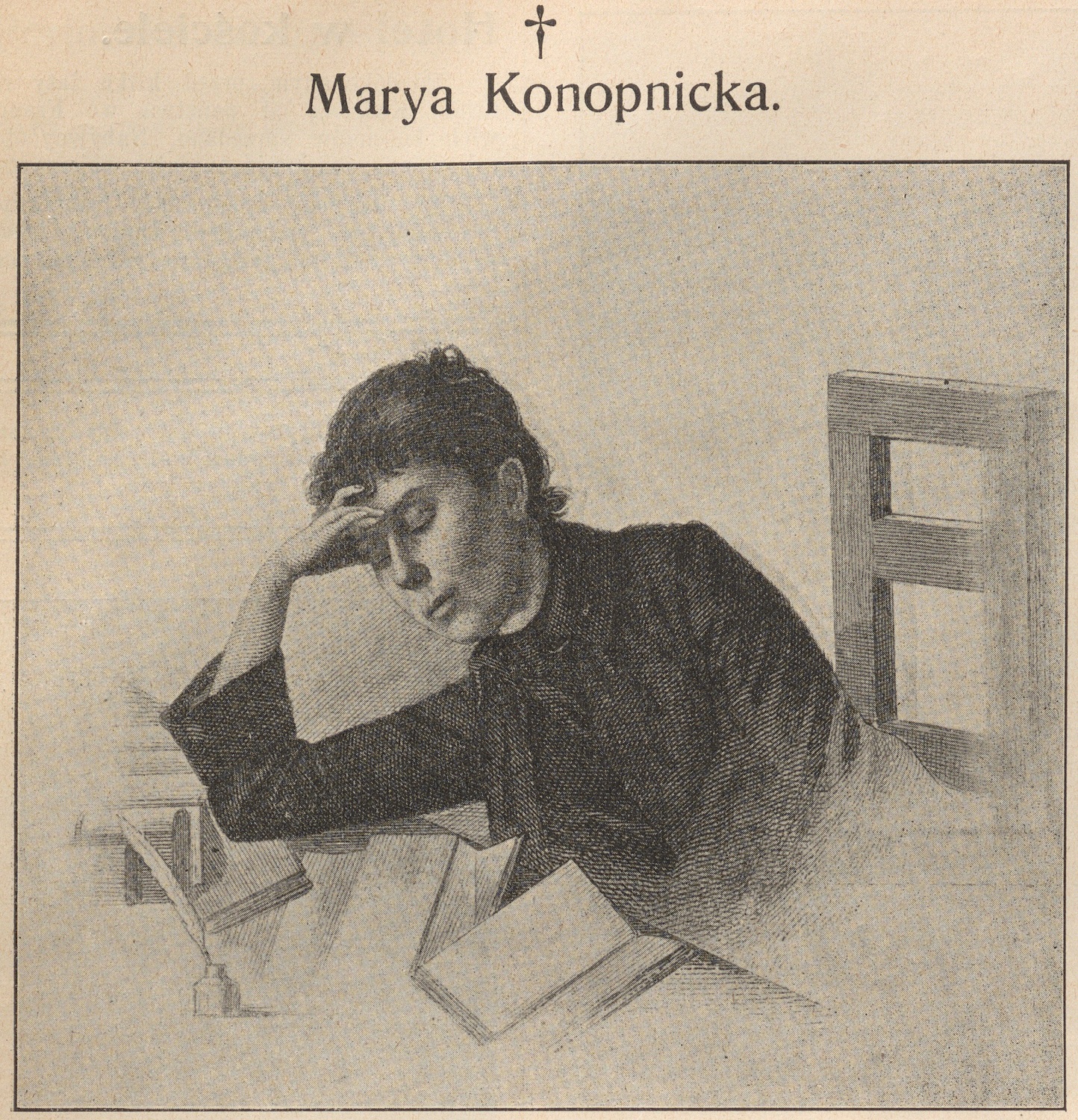

The funeral of the writer Marya Konopnicka on November 10, 1910 was even more "national." A special committee for the preparation of the ceremony was created by the City Council, and numerous Polish societies and organizations joined the farewell.

When the body was taken out of the Bernardine monastery church, the vice president of the city of Lviv, Tadeusz Rutowski, spoke from a temporary rostrum. Then the procession went to the monument to Mickiewicz, which by 1910 had already become a mandatory point of every patriotic event, then through Akademicka, Fredra, Kamienna and Piekarska Streets to the Lychakivsky cemetery.

The list of participants also emphasizes the importance of the event and the level of civil society development: pupils of orphanages, schoolchildren, students of the University, Polytechnic, Veterinary and Agricultural academies, workers' and women's associations, veterans of the January Uprising, the Sokół members, volunteer firefighters, professional and creative unions, the Rifle Association, as well as members of the Diet (Sejm), the Parliament, and the City Council. There was also an honorary "civil guard" and a human corridor formed by schoolchildren.

A theater orchestra played near the monument to Mickiewicz; in front of the church, it was replaced by the Liutnia society, and at the cemetery, by the Ekho society. In addition to the deputies of the Diet (Sejm) and the State Council, delegates from Krakow, Warsaw and Poznań made speeches.

Actually, it was a nationwide event comparable to the funerals of archbishops. The difference was that instead of priests, representatives of the national movement came from all over the region.

Funerals of the Ukrainian movement figures

To better understand the practices that existed during the funerals of Ukrainian figures, several examples can be used. The reburial of Markiyan Shashkevych, like the funeral of Volodymyr Barvinskyi, turned into a Ukrainian national manifestation. In these events, features characteristic of all Ukrainian manifestations of that time can be seen: the mobilization of peasants and the leading role of the clergy. On the other hand, Ivan Franko's funeral in 1916, despite the absence of villagers due to the war and the non-involvement of priests due to issues with Franko's atheism, became the most massive Ukrainian event in Lviv.

In an article dedicated to the funeral of Anatol Vakhnianyn on February 12, 1909, the newspaper Dilo described Lviv, where Vahnianyn had lived, as a foreign land in contrast to his native Stryi, where the deceased was truly loved and respected. About 40 representatives of various Ukrainian societies came to the funeral from the vicinities of Stryi. Wreaths were decorated with blue-and-yellow and red ribbons (the latter were considered mourning ones).

Several thousand people took part in the "march through the streets of our capital", according to the Dilo estimate (probably overstated). Among them were members of church brotherhoods, deputies from the Stryi region, the orchestra of the Stryi gymnasium and the Boyan choir, students, Greek Catholic seminarians, and clergy. Representatives of Ukrainian associations and organizations were also present, that is, not only peasants led by priests, but members of a much more developed society. Yevhen Olesnytsky, a Parliament member, spoke over the grave at the Lychakivsky cemetery.

The funeral of a socialist activist

There were also funerals that had a rather distant relation to the then traditional idea of this ritual. In May 1905, Kazimierz Mokłowski, an architect and a socialist movement activist, was escorted on his last journey by Lviv socialists (it is important to understand that Austro-Marxism, widespread in Galicia at that time, was rather different from the version of socialism known to us), architects and "admirers of his talent." When the coffin was taken out of the house on Miłkowskiego Street 11 (now Hulaka-Artemovskoho Street), on the nearby Kochanowskiego Street (now Kostia Levytskoho Street) workers gathered, whom the deceased "had led to fight for a better future and human rights", as well as architects and monument conservators. The workers' choir, the choir of the Zoria association, and the technicians' choir were singing. Songs were performed in Polish and Ukrainian: a linguistic parity of this kind was typical of Lviv socialists. Józef Hudec spoke from the balcony on behalf of the Lviv PPSD organization.

Workers and members of the Socialist Party took part in the march along ul. Kochanowskiego, ul. Batoriego and ul. Pekarska to the Lychakivsky cemetery. The "workers' coat of arms" was carried in front, and instead of wreaths, decorations and orders, ornamentations made of weeping willow and birch were used. Among the speeches at the cemetery — and they were on behalf of the masons, the socialists of Przemyśl, and the USDP — the most interesting was the speech of one of the socialist leaders, Ignacy Daszyński. He mentioned "a bloody sun rising in the East" (apparently, the Russian revolution), which the deceased would no longer see. When the coffin was lowered, workers' songs and the Red Flag anthem were sung.

***

Thus, funerals in Lviv during the period of autonomy were real political manifestations. Their massiveness and pomp were supposed to show the success of "the cause" or to testify to current political processes, like the funerals of Adam Kotsko or Andrzej Potocki.

Political activists adopted many things from church rituals. Imperial rituals were also copied, with the use of certain elements of the emperor's visits during the events, such as honour guards, torches, arches.

The funerals of ecclesiastics, on the contrary, took on an openly national character. Instead of a telegram from the Vatican with condolences on the death of the archbishop, we can see telegrams from Warsaw and Poznań from well-known figures of the national movement. Instead of monks and priests, the main role was played by representatives of patriotic or political societies, with city officials and schoolchildren instead of military guards.

The Ukrainians were inferior to the Poles in terms of organizational abilities, having fewer institutions, due to the need to come to Lviv for a funeral, etc.

However, as the mass funerals in Lviv demonstrate during the times of autonomy, both the Ukrainian and even more so the Polish community were parts of a much more developed civil society, capable of mobilizing its members. Progress during the last third of the 19th century was colossal.