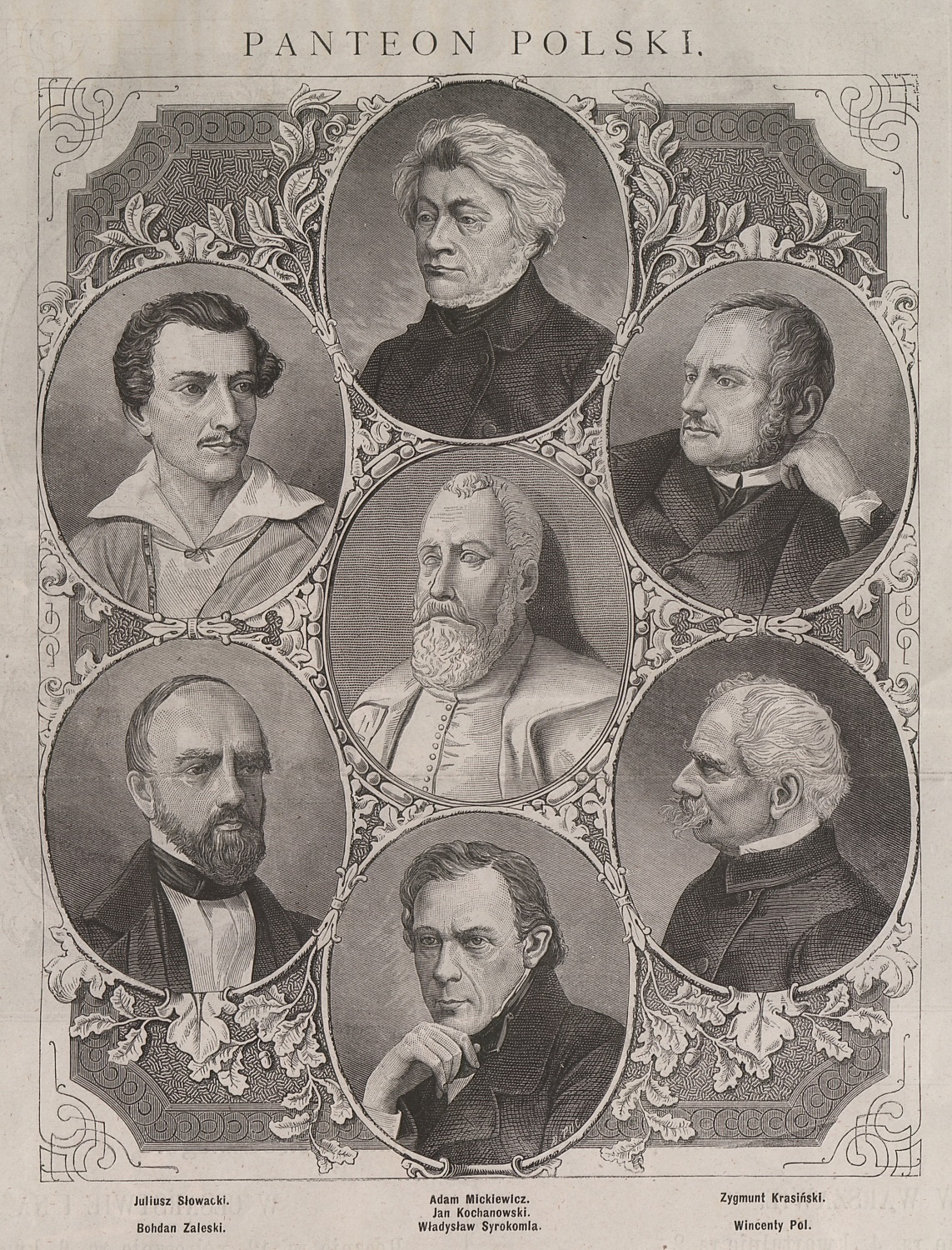

In the second half of the 19th century, an important part of nation building was the development of literature. Writers and poets were not only authors, but also the "voice of the people." This fit the ideological scheme according to which a nation should develop in the cultural sphere of its own language. Thus, the cult of the poet-prophets (above all Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki) was one of the cornerstones on which Polish identity was built. The "kings of the spirit" of Polish Romanticism provided an understanding of what the Polish past had been and what the Polish future should be. In the Ukrainian national project, the situation with Ukrainian poets was similar.

As befits a cult, a calendar of birthdays, deaths, book releases, or the publication of individual works was formed around national poets. This was common to both Poles and Ukrainians and allowed them to regularly "remember" poets and "educate" the younger generation.

Later, in the interwar period, a so-called "political religion" can be discussed, which openly competed with Christianity. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the development of the cult of "poet-prophets", although sometimes contradicting Catholic doctrine, did not yet provoke an open conflict with the Church. Rather, it was an attempt by a section of the secular intelligentsia to compete with the clergy for influence over the masses. It was also about the ideology of modernism, which the Vatican fought against as a "slippery slope to atheism" and which undermined some of the teachings of the Catholic Church. The essence of the problem was that the proponents of modernism took Church dogmas and even Scripture critically rather than literally. This led to interpretations that challenged the authority of the hierarchy.

The situation was complicated by the fact that at the time of the spread of nationalism, there were more people among the hierarchs themselves, both Roman Catholics and Greek Catholics, who could be considered national. Finally, the monarchy and the universal nature of Catholicism were receding more and more into the background, giving way to the patriotic feelings of the clergy.

On the one hand, there was a conservative vision of the Catholic Church as the supreme authority, not limited by national borders, and the interpretation of the commandments as inviolable law. On the other hand, there was the justification of the sin of manslaughter by patriotic feelings, the interpretation of the Jesuits and Crusaders as invaders, and criticism of the Vatican because of political differences. Finally, Juliusz Słowacki criticized Pope Gregory XVI for condemning the November Uprising.

Słowacki and Mickiewicz Between Patriotism and Catholic Conservatism

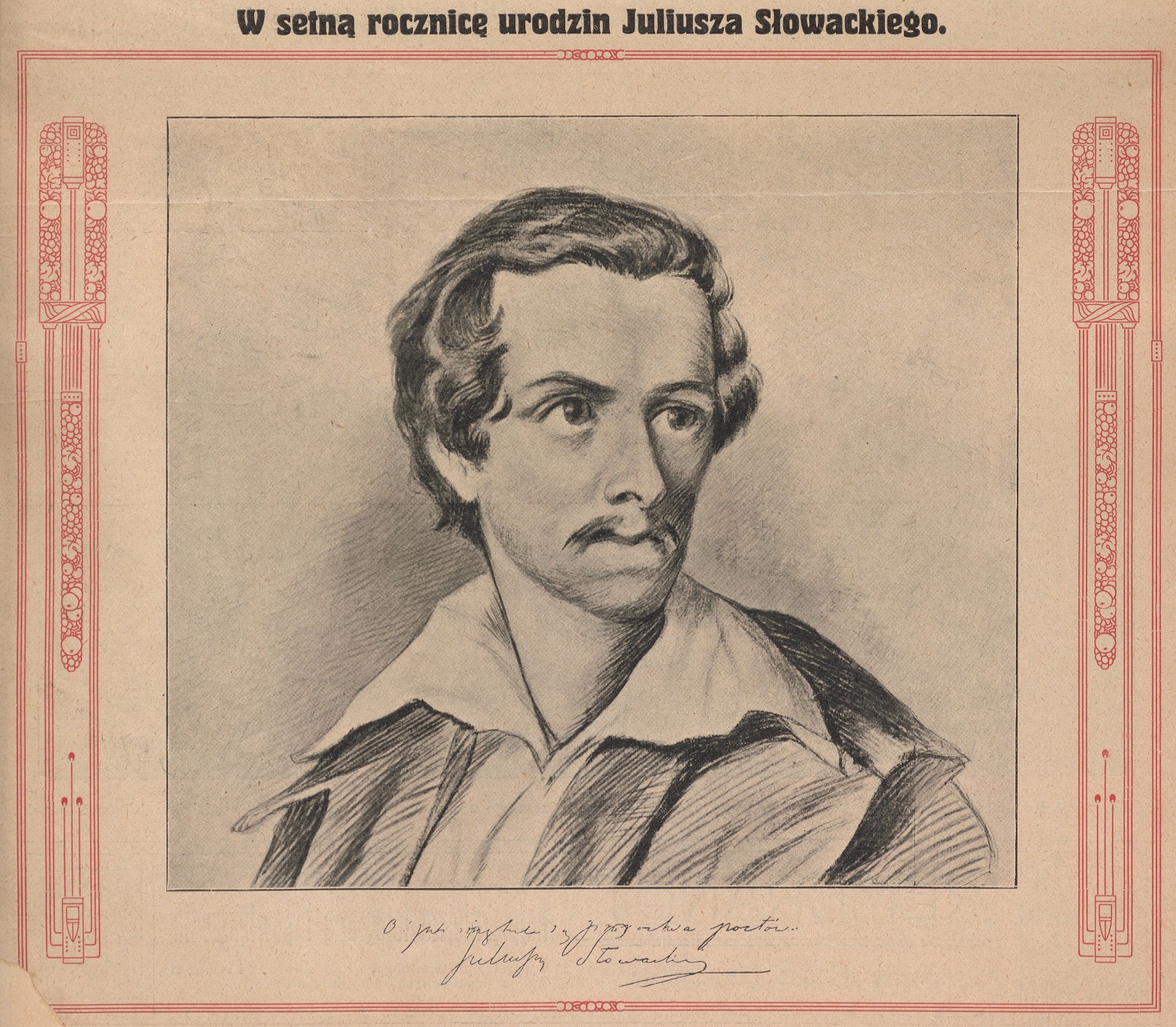

In 1909, on the centenary anniversary of Juliusz Słowacki's birth and the 60th anniversary of his death, the clerical periodical Gazeta Kościelna published an article that perfectly illustrates the clergy's desire to adapt to the conditions of the time, i.e. the conditions of the emergence of a new cult and a new "saint". It was not easy, because Słowacki had a positive interpretation of Martin Luther, described the transition from paganism to Christianity as "a rejection of the faith of the ancestors," did not take certain church dogmas seriously, participated in duels, and thought thoroughly about suicide. He also considered the Vatican and the Jesuits a threat to the future of Poland. The Gazeta Kościelna attributed all this to the poet's "melancholy" because the main thing was that he "was a patriot and really believed in God." Therefore, this clerical newspaper argued, "godless socialists" had no right to consider Słowacki their patron and to use his authority for anticlerical agitation.

Naturally, the non-clerical press went even further in creating the cult of the new prophet. The newspaper Wiek Nowy, describing the same anniversary in 1909, wrote that "100 years ago destiny gave the people a prophet, an immortal creator." The poet's mother, Salomea, was "chosen by God to give Poland a genius."

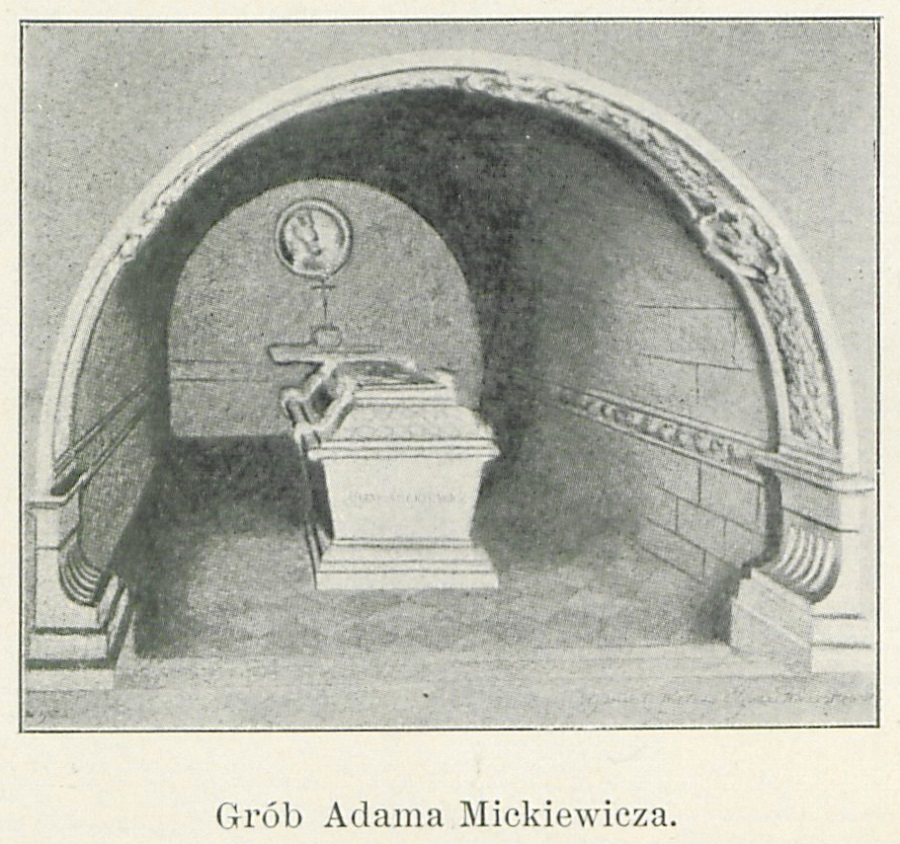

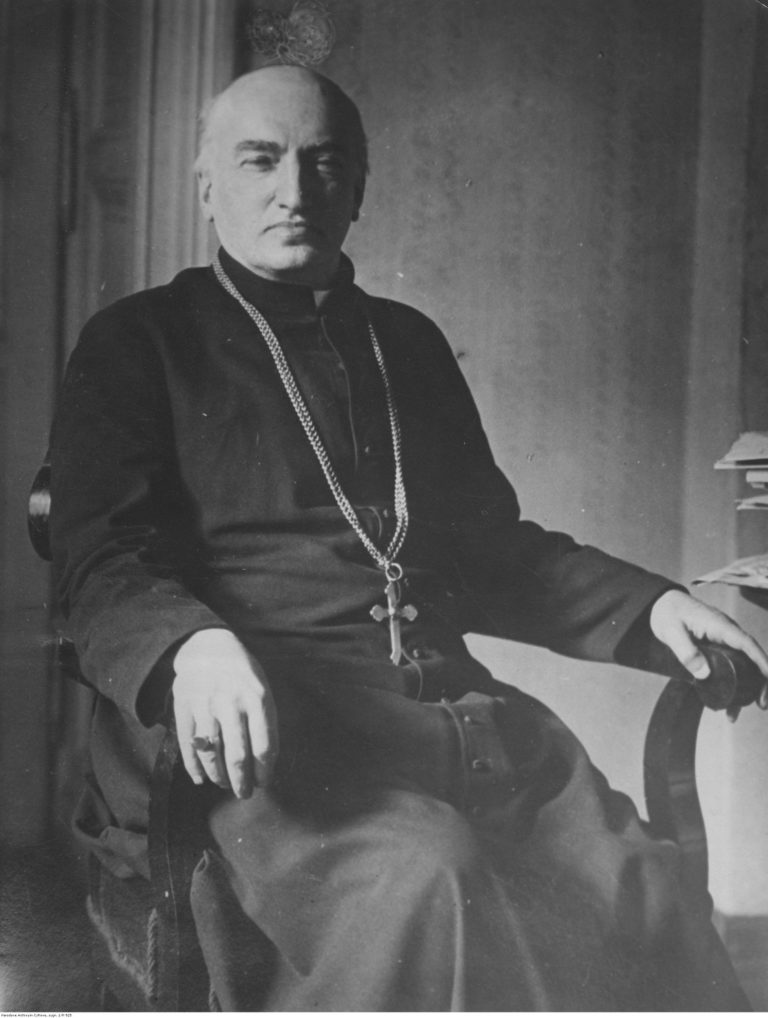

Therefore, when Cardinal Jan Puzyna opposed the transfer of Juliusz Słowacki's body to Krakow, to the crypt on Wawel Hill, where it was to be buried next to the body of Adam Mickiewicz, which had already been transferred there, it was not an argument against it, but rather another factor of mobilization for the patriots. After all, the idea was to transform the tomb of the Polish kings into the crypt of the "Three Prophets and Kings of the Spirit": Mickiewicz, Słowacki and Krasiński.

- Ян Пузина / Jan Puzyna

- Гроб Адама Міцкєвича / Adam Mickiewicz Tomb

At the beginning of the 20th century, the cult of the national prophets gained the right to exist alongside traditional cults, became part of the calendar, and needed places to hold events: tombs, monuments, squares, and so on.

Lviv and the cult of Polish "poets-prophets"

Traditionally, on the anniversaries of Mickiewicz (24.12.1798 – 26.11.1855) and Słowacki (4.09.1809 – 3.04.1849), special evenings were organized in schools, societies and institutions. Their works were recited, lectures were read, musical programs were organized. In the course of time, these events turned into the Autumn Evenings of the Three Prophets, where money was raised for various patriotic causes.

When it came to the cult of Adam Mickiewicz, Lviv was clearly inferior to Krakow. As in the case of Jan Sobieski or the commemoration of the Battle of Grunwald, it was the burial place — the crypt of Wawel Castle — that attracted Polish patriots from various empires. Lviv's status as the capital did not help much.

Krakow was logically the center of the celebrations on July 4, 1890, when Adam Mickiewicz was reburied there. The reburial itself was made possible by the autonomy of Galicia within the empire. All the activists who could afford it went there, while for those "Lviv residents who remained in Lviv," according to the press, a solemn evening was organized in the assembly room of the City Hall.

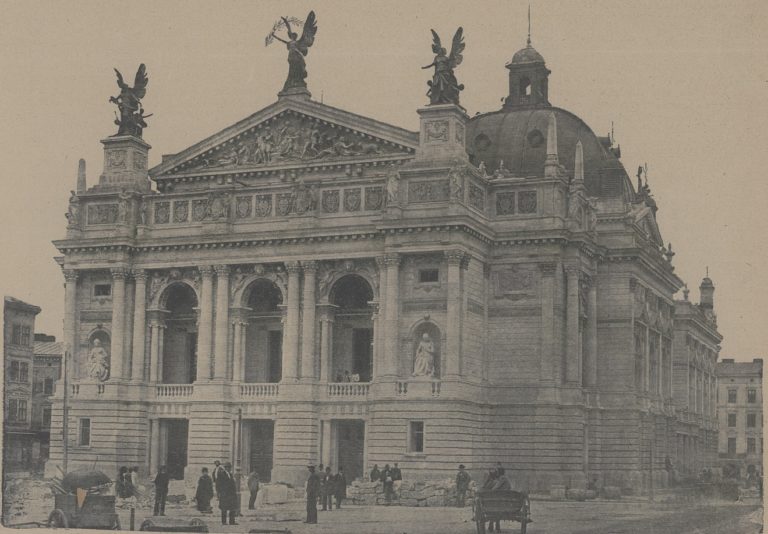

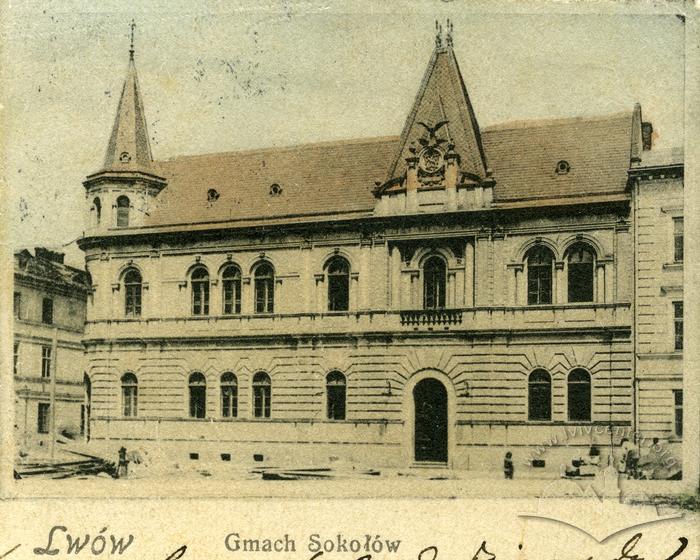

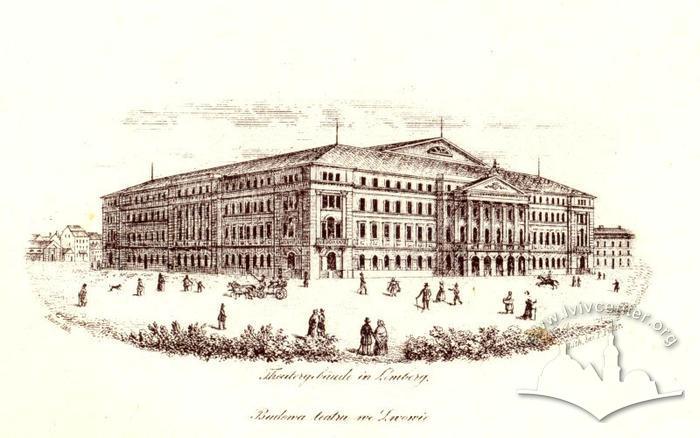

During the centenary of Mickiewicz's birth in 1898, public attention was focused on the unveiling of the monument in Warsaw. Therefore, it was decided to hold the celebration in Lviv on a different date, July 21-22, 1898, so that the two events would not overlap. On Saturday, July 21, a solemn evening was held in the hall of the Sokół Society. On Sunday, the next day, the town woke up to the sound of the "wake-up call" of the Harmonia Choir. At 8 a.m. people gathered at Rynok Square, and an hour later a thanksgiving service was held in the Latin Cathedral. From there, the participants marched through the city center, though not directly, to the site of the future monument to the poet on pl. Mariacki, where a rally was held. In the afternoon, lectures were held in the city's schools and a gala performance was held at the Skarbek Theatre. All these events were accompanied by fundraising for the future monument. The problem of funds was quite acute, so the organizing committee made a special appeal to Lviv residents to decorate and light their houses, since the city council did not allocate any money for lighting.

The solemn inauguration of the monument took place on October 29, 1904.

In 1909, the centenary of Juliusz Słowacki's birth and the 60th anniversary of his death, Lviv became the center of celebrations. The poet's body had not yet been reburied on Wawel Hill in Krakow, and the Lviv City Council supported the idea of "transporting the bodies of the kings of the spirit, the prophets, to the burial place of the Polish kings," while creating an organizing committee to celebrate the anniversary in the "capital of the province." Similar committees were created for Galicia, Silesia and Bukovina. In addition to holding celebrations and producing souvenirs such as portraits, busts, and medals, an important task was to raise funds for a monument to Słowacki in Lviv.

At the same time, various milieus prepared for the anniversary. For example, the student artistic and literary circle "Życie" (Life) in Krakow addressed the "Polish youth" with the idea of publishing a special book about Juliusz Słowacki — "the prophet of Poland, the guiding star, the king of the spirit, the holy book".

As early as March 1909, commemorative evenings dedicated to Słowacki began, first in the City Hall and later in schools and societies. During these events, funds were collected for the future monument. Meanwhile, the reburial of the poet in Krakow was being organized.

Emphasizing the status of the "capital" and the main organizer, the Lviv organizing committee announced its intention to publish a commemorative book describing "all the events in Poland and abroad" dedicated to Słowacki's 100th birthday. It was also decided to separate the events in the province from those in Lviv.

It was traditional for such celebrations to make cards for the illumination. The image itself was commissioned from the Krakow artist Piotr Stachiewicz, and all local organizing committees were advised to follow the same sketch. Silver and bronze commemorative medals were also produced in Krakow. In August, it was discovered that a Krakow businessman was selling his own stickers and sharing the profits 50/50 with shop owners, thus "bypassing" the fund for financing the monument in Lviv. The organizing committee called for a boycott, although the reasons for this "shameful situation" later became known. The businessman asked for stickers, but did not receive them, so he decided to act on his own.

The news that Cardinal Puzyna had blocked the transfer of the poet's ashes to Wawel Hill was met with strong rejection. Thus, on Saturday, May 29, 1909, the students in Lviv organized a "general meeting" in the hall of the Polish Pedagogical Society. There, they compared the position of the clergy with the policy of the Russian tsar, and gathered later at the Adam Mickiewicz monument. Notably, they did not invite the nationalists from the Academic Reading Room.

Since it was impossible to rebury Słowacki in Krakow, the idea of erecting a monument to the poet in Lviv came to the fore. It was to be the first public monument to Słowacki in the "Polish lands," and thus a matter not only of the city, but of the entire nation. Therefore, the Lviv Committee called upon all those who were organizing events dedicated to the centenary of Słowacki's birth to donate them to the fund for the monument's inauguration.

In general, the Lviv organizing committee tried to get involved in matters far beyond the city. For example, it organized the sale of Słowacki's plaster casts throughout Galicia and was involved in the installation of a memorial plaque in Pidhirtsi, where the poet's father was born. On Sunday, October 3, the plaque was unveiled on the wall of the local church in the presence of many Lviv residents, as the committee had arranged discounts on the train from Pidzamche to Zolochiv and back.

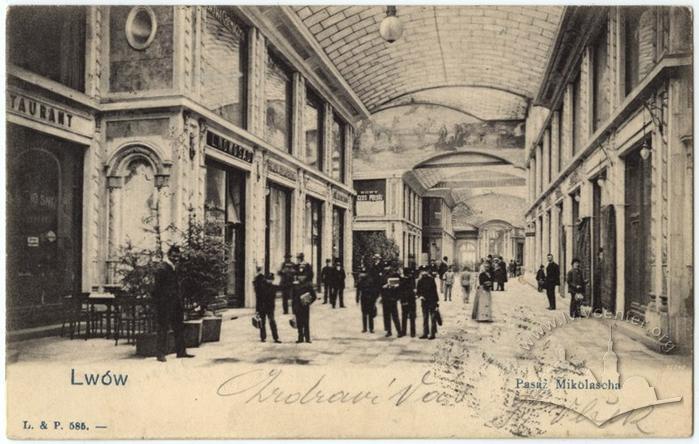

The program of the Lviv celebrations on October 28-31 (from Thursday to Sunday) 1909 was as follows. On the evening of October 28 (Thursday) at 10 p.m. the guests of the festival were received in the hall of the Literary and Artistic Circle in the Mikolasz Passage. On Friday, the opening of the Słowacki Historical and Literary Congress took place in the assembly room of the City Hall, followed by a performance in the City Theater in the evening. On Saturday, October 30, there was a congress in the City Hall, performances for schoolchildren and adults in the theater, and a party in the City Hall in the evening. Sunday, October 31, began with a musical wake-up call, followed by solemn services in the Latin and Armenian Cathedrals, the Evangelical Church, and a synagogue (Tempel). A march from the Latin Cathedral to the City Theater, accompanied by the "hejnals" from the City Hall Tower, was followed by the opening and blessing of the cornerstone at the site of the future monument near the City Theater. In the evening of the same day, performances were held in the theater and celebrations took place in various parts of the city.

The idea of blessing the cornerstone of the future monument allowed Lviv to become the center of all-Polish celebrations. As the press of the time reported, the monument was not allowed to be erected in Warsaw, while in Poznan it had to be "hidden" in the foyer of a theater. Therefore, Lviv "had the duty" to represent "the whole of Poland". And on the anniversary, "the eyes of every Pole were on Lviv."

During the celebrations, the city was decorated not only with stickers and busts, but also with flags. Most of them were national flags, and almost no one used city symbols or provincial colors. All the stickers, of which the committee had printed 70,000, were sold out, and even the windows of the trams were decorated with portraits of Słowacki.

The Latin Archbishop Józef Bilczewski and the Armenian Archbishop Józef Teodorowicz (showing their choice of "Polishness" at the expense of "Catholicism"), Marshal Stanisław Badeni, Governor Michał Bobrzyński and other representatives of the elite took part in the ceremony at the City Hall. On the march to the laying of the foundation stone there were many socialists, their wreaths decorated with red ribbons. In general, very different political groups were represented, although there was no question of "unanimity" in Polish circles. First, there were the clergy and supporters of Cardinal Puzyna. Second, nationalist students (supporters of Endecja, the Polish National Democrats) traditionally tried to "speak on behalf of all Polish youth", otherwise they threatened to "brightly" protest against the committee.

After the celebration it was decided to collect the used cards and send them to the villages where it was necessary to "raise patriotic consciousness". Commemorative evenings, lectures and concerts in societies and schools continued for some time; only in mid-December the committee was dissolved and the results of its work were summarized. It was also decided to set up a committee to publish a book on Słowacki's centenary and a committee to build a monument.

* * *

Thus, the "poet-prophets" occupied an important place not only in the patriotic calendar, but also in the city space. The monument to Mickiewicz was a place of regular celebrations and spontaneous meetings. The laying of the foundation stone for the monument to Słowacki (which was never built) allowed Lviv to secure a conditional patriotic primacy among the "Polish cities", at least for the duration of the celebration of the poet's 100th birthday. It should be added that the central streets of Lviv during the period of autonomy were also named after Polish "poets-prophets".

Traditionally, Ukrainians tried not to react to "fictitious anniversaries," as they called such events. Nevertheless, they actively adopted the practice of honoring their own poets-prophets.