November in Lviv was traditionally full of Polish national celebrations. It was in this month that the beginning of the November Uprising was celebrated and the anniversary of Adam Mickiewicz's death was commemorated.

The troubled year of 1905 was no exception. The atmosphere in society was tense.

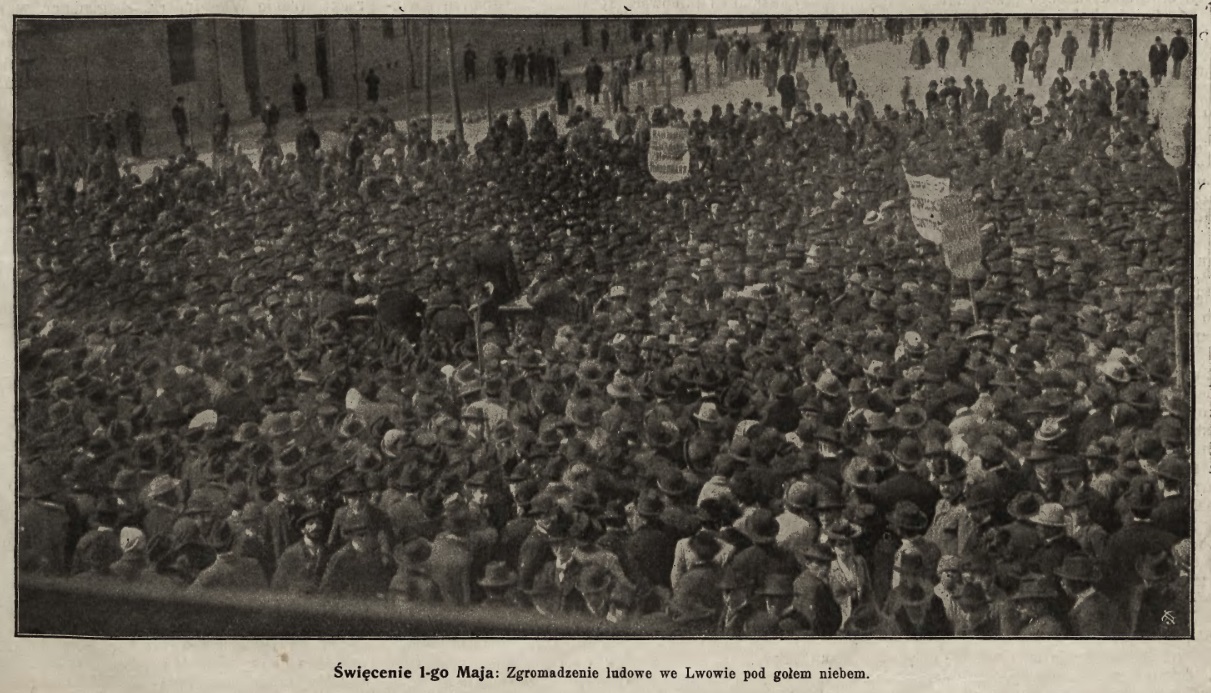

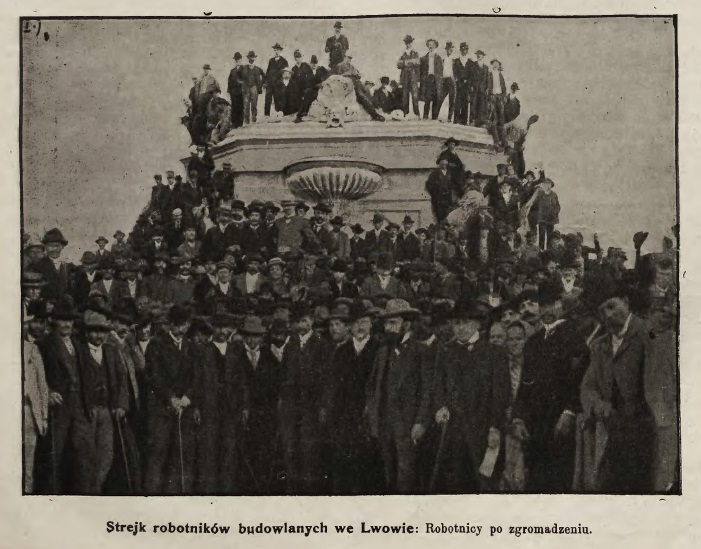

In the spring and summer, strikes were organized by leftist politicians in Lviv and regular actions of solidarity with the revolutionaries of the Kingdom of Poland were held; in addition, in late October it became clear that the constitution "granted" by the tsar did not apply to the Polish lands of the Russian Empire. All this affected the course of traditional November patriotic actions in Lviv, especially those in which nationalist youth took an active part.

Consequently, right-wing activists in Lviv were still able to make themselves known and heard, partially seizing the initiative from the local social democrats. However, this happened rather because of the unsuccessful actions of those organizing nationalist youth's events as they were unable to prevent pupils and students from conflicts in the streets.

The level of nervousness in the city is shown even by the course of the usual November charity parties. These events were traditionally accompanied by dancing parties, but it did not befit patriots to dance due to mourning over the Russian repressions in the Kingdom. And so, when it came to music, one part of the guests demonstratively did not have fun and attacked the less "conscious" guests for their lack of a patriotic stance.

Arrival of the Hungarian Youth

In November 1905, 17 representatives of Hungarian youth organizations came to Lviv in response to the previous year's visit of the Lviv Academic Choir to Budapest.

The Polish press reported about "historically" friendly relations that had developed between the Poles and Hungarians. In addition, the periodicals emphasized that the interests of the two peoples coincided in view of their aspirations for greater "national rights" within the empire. The visits of young people were compared to the "congresses of kings" of the past.

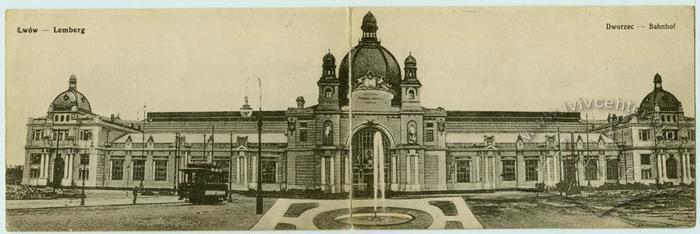

On Sunday, November 5, at 8:20 a.m., a train with delegates sent by Hungarian associations and societies arrived at the Lviv railway station, accompanied by Erno Kovacs, a member of parliament. The guests wearing Hungarian national costumes were greeted by the Academic Choir on the platform. The Hungarian and Polish national anthems were sung, the guests and hosts exchanged greetings, and the Hungarians sang "Boże, coś Polskę"; then everyone went to the Polytechnic for breakfast.

The guests were welcomed at the Polytechnic at 11:00 by the leaders of nationalist student organizations, the Ogniwo workers' association, the vice-president of the city of Lviv Stanisław Ciuchciński, some members of the City Council, professors and the administration of the educational institution. One way or another, the topics raised by speakers always revolved around references to the "glorious past of the two enslaved peoples."

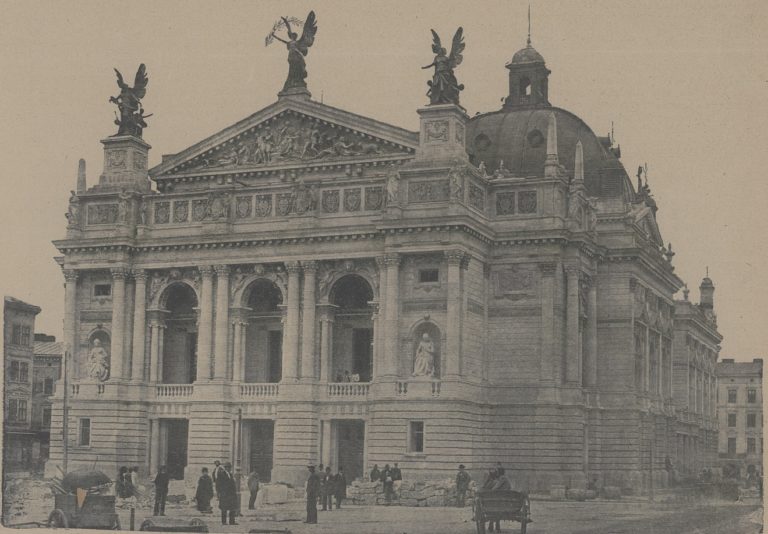

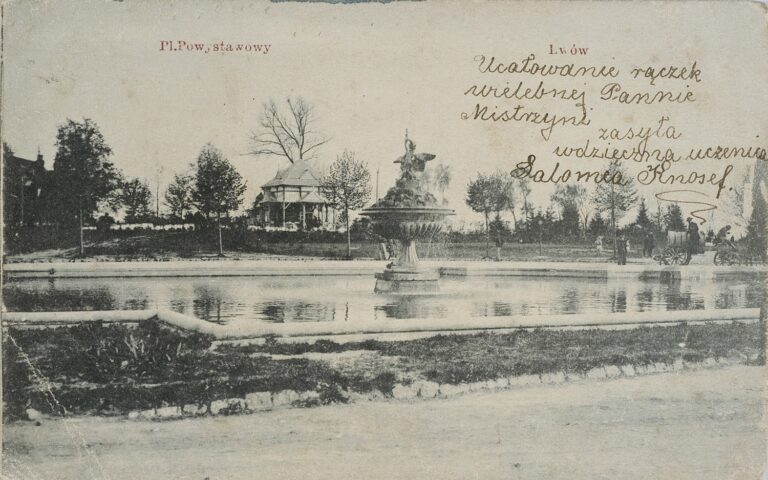

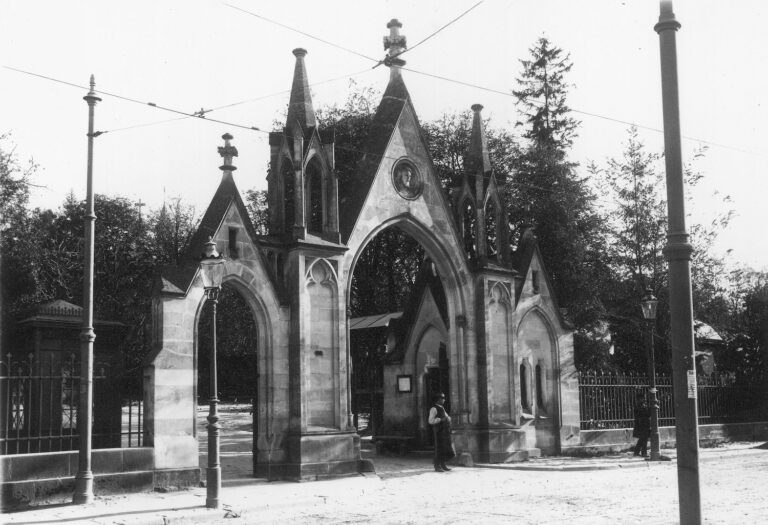

At 16:30, the guests first laid wreaths at the monument to Adam Mickiewicz, then at the monument to Kornel Ujejski; at 7:00 p.m. they went to the City Theater. There were also many gestures of the "patriotic friendship" as the theater orchestra played the "Rakoczi March", the Hungarians shouted "long live independent Poland", everyone sang national anthems together. After the theater, there was a march to pl. St. Spirit, and then a student party.

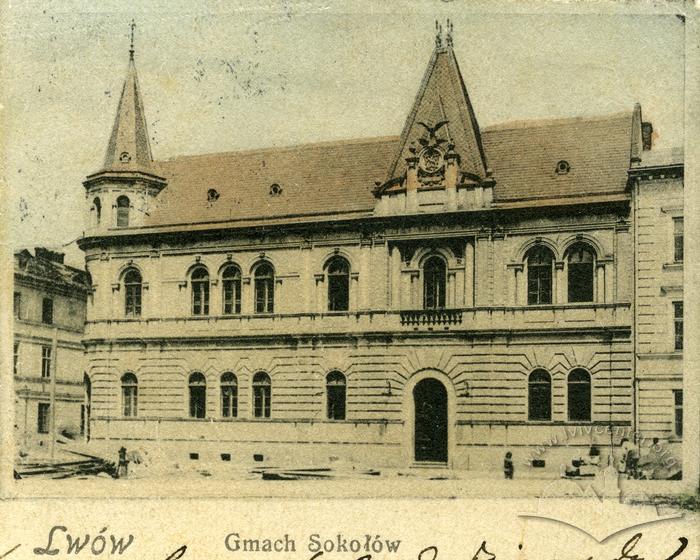

On Monday, November 6, the guests were shown the Ossoliński Institute, the Lubomirski Museum, the University, the Diet (Sejm), and the Panorama of Racławice. In the building of the Diet, the Hungarians had a meeting with the president of the city of Lviv, Michał Michalski, wishing him "to see an independent Poland." In the afternoon, a festive reception was held at the Strzelnica (Shooting Range). On November 7, a meeting was held in the "Falcon-Mother" society's assembly room, where the City Council was also represented.

So, the program was quite patriotic and presentational, and it all should have passed smoothly. However, the socialists (students predominating among them) actively opposed it. During these few days, they constantly tried to disrupt their ideological opponents’ actions. Trying to shout over the speakers, they appeared both in the assembly hall of the Polytechnic and near the monument to Mickiewicz. They were pushed out of the hall and beaten near the monument, Semen Vityk being injured among others. It is not known whether the socialists purposefully came to pl. Mariacki towards the evening of November 5 to spoil the laying of flowers by the nationalists and the Hungarians at the Mickiewicz monument. They may not have finished their demonstration, when the police tried to confiscate their red flags.

Another interesting point is that while the populists, centered around the Dilo newspaper, interpreted the Galician social democrats as a Polish movement in which the Ukrainians act in the Polish interests, the national democrats, centered around the Słowo Polskie, described the actions of the PPSD as "provocations of the socialists and Ruthenians" who worked against the Polish national project.

Clashes Near the Consulate

Public opinion regarding the events in the Kingdom of Poland was dominated by the idea that the tsarist government was not implementing a constitution for the Polish lands due to the insistence by the Germans. Thus, there were two institutions in Lviv that were considered directly "responsible" for the Polish national tragedy: the consulates of Russia and Germany.

On November 14 at 20:00 (2 days after the violent dispersal of a Ukrainian demonstration on the anniversary of the siege of Lviv by Khmelnytskyi), several hundred students of the University and Polytechnic, as well as some part of young workers, decided to express their indignation in front of the consulates.

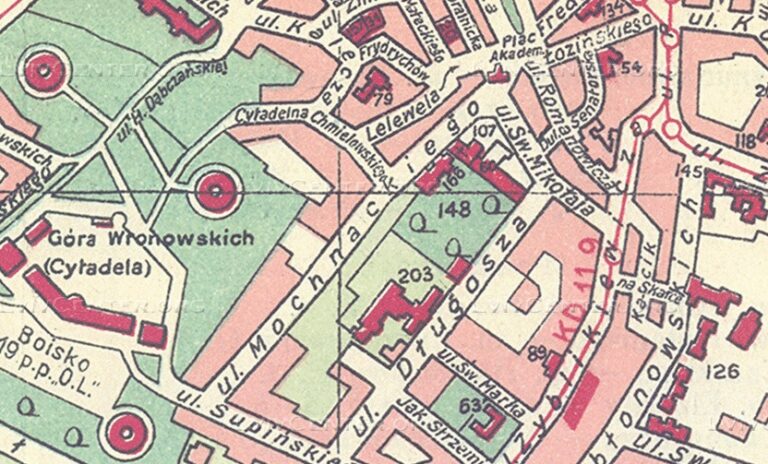

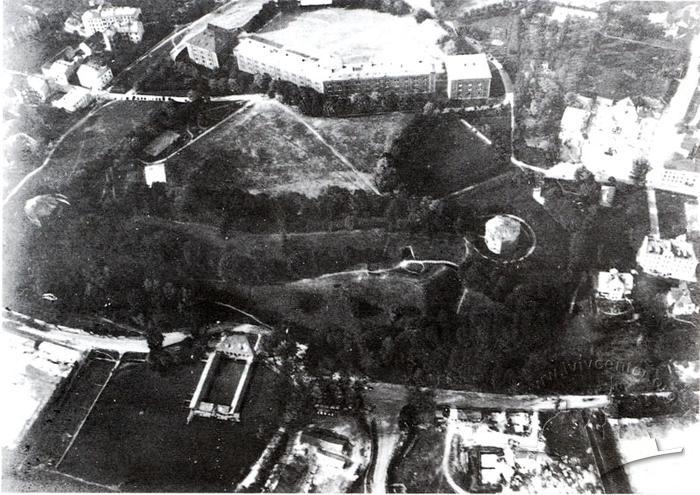

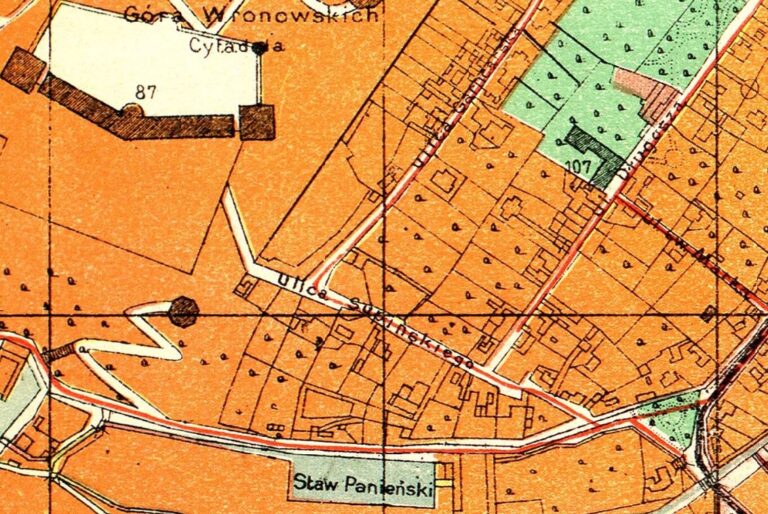

The Russian consul’s residence on ul. Sykstuska was well guarded: the police blocked the street from both sides completely. Therefore, the young people went to the German consul, who resided on ul. Mochnackiego, where there was less police forces. Groups from the Polytechnic, approximately 500 people, made their way from the direction of the Citadel, through ul. St. Lazarus and ul. Supińskiego. Then they started throwing stones and bricks at the policemen, who did not let the demonstrators through. Mounted and foot police units dispersed the demonstrators with their sabers. A bit later there was a shootout between the demonstrators and the police, fortunately, without serious consequences, as the injuries (four on each side) were inflicted exclusively by cold weapons.

Meanwhile, another group of students, about 200 people, tried to break through to ul. Mochnackiego from the direction of the University. They threatened the policemen with revolvers, but there were not only students among the demonstrators. Someone "senior" dissuaded them from shooting, and the whole group marched to the monument to Mickiewicz, singing patriotic songs and shouting "Long live the Warsaw Sejm!"

The governor, Count Andrzej Potocki, went to the skirmish site and spoke with the consul; the president of the city, Michał Michalski, did the same. Since the evening session of the Diet (Sejm) was still going on at that time, some deputies also arrived at the University. Rectors of the Polytechnic and the University met and signed an appeal to the government commissioner regarding the shooting and in support of the students.

Naturally, the "massacre" in the city center was widely talked about. The Polish patriotic press reported that the students, marching peacefully with several torches, had just wanted to demonstrate their dissatisfaction with the policies of Russia and Germany, while the police allegedly took out their sabers and bayonets immediately and then started shooting at the retreating students who were carrying their wounded comrades. According to various sources, there were significantly more wounded students than four (four were actually reported only by the government-run newspaper). In the end, they wrote that only "the senior students' foresight prevented a repetition of the bloody year of 1902."

It is noteworthy that when the police reported on their actions of November 12 and 14, the dispersal of the Ukrainian demonstration with cold weapons was not at all considered extraordinary. Instead, the use of firearms on November 14 required "further investigation" as this could have been an "abuse" (excess of powers).

Patriotic School Students in the Late November 1905

School students also joined the patriotic revolutionary fervour of 1905.

On Saturday, November 18, at 19:00, a "school student assembly" was held near the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. A small gathering, about a hundred people, advocated the reform and "nationalization" of the school: a reduction in the number of lessons in classical philology and religion, an increase in Polish literature, as well as the abolition of "supervision of students' conscience." In addition, there was a completely relevant political program: the students held banners reading "Down with the tsar!" and "Long live Poland!"

On November 21, 1905, school students honored the victims of repressions in Russia at the Lychakivskyi cemetery. This time the evening was dedicated to those killed and repressed in the town of Kroże (now Kražiai, Lithuania), where in 1893 a church was forcibly closed. There were patriotic speeches and singing of anthems, followed by a march with torches to the monuments to Ujejski and Mickiewicz. At the same time, as the populist periodical Dilo remarked, the Polish press did not call it "youth getting wild", although these were the words with which the "Ukrainian Haydamaks’" actions were described.

The most interesting thing happened, however, when schools officially held celebrations dedicated to the November Uprising. The programme for November 29 included morning services in the city's churches from 8 to 10 a.m.; later, after two hours of studying, a lecture on the uprising was planned.

Yet the students of the 1st Realschule decided that this was not enough. Therefore, after a divine service in the Poor Clares church on ul. Łyczakowska, they, "to the great surprise of their professors", lined up in a column, four in each row, pulled out a red banner with a white eagle and went not to the school, but in the opposite direction, to ul. Piekarska. Near the church of the Resurrectionist Fathers, they met the students of the VI gymnasium, who were just leaving after a service. Together, students of the two institutions marched to the V gymnasium building on ul. Wałowa, where they were joined by another group of students.

Singing songs and shouting patriotic slogans, the crowd of school students headed for the building of the IV gymnasium located behind the City Park. The door was closed, because studies had already been resumed there. After shouting "Shame!" at the directorate, the students went across pl. St. George to ul. Szumlańskich, where the 2nd Realschule was located.

The school management had already been warned about the demonstration, so the door was also locked. The young demonstrators, though, managed to enter the school yard through the yard of a neighbouring house. In the yard of the educational institution where classes were being held at that moment, they began to sing patriotic hymns, and the students of the 2nd school opened the windows in their classrooms and joined the singing. This encouraged the "guests", they broke down the door and from the school corridors started calling the students to join.

The teachers were confused. One of them even tried to drive the crowd out with a stick, but he was beaten. Then the students broke the school windows, while some of the demonstrators even rushed to the beaten teacher's flat to break windows there as well. The teacher himself tried to escape, but he was caught. In the end, the "guests" began to enter the classrooms and drive youngest pupils out into the yard. At that time, it was not only schoolboys, as in the beginning, but also university or Polytechnic students and even workers who joined them.

After the "success" in the 2nd Realschule, the youth tried to return to the closed 4th gymnasium, but a police unit blocked their way. The banner with the white eagle was snatched by a policemen from the hands of a schoolboy, so a fight nearly broke out. In the end, after "senior comrades" settled the situation, the students continued their march heading, though, for the monument to Mickiewicz. After singing and speeches, they wanted to go back to their schools, but the schools were already closed. Therefore, the programme was continued at the Lychakivsky cemetery from where (now with torches) they marched back to the monument to Mickiewicz again.

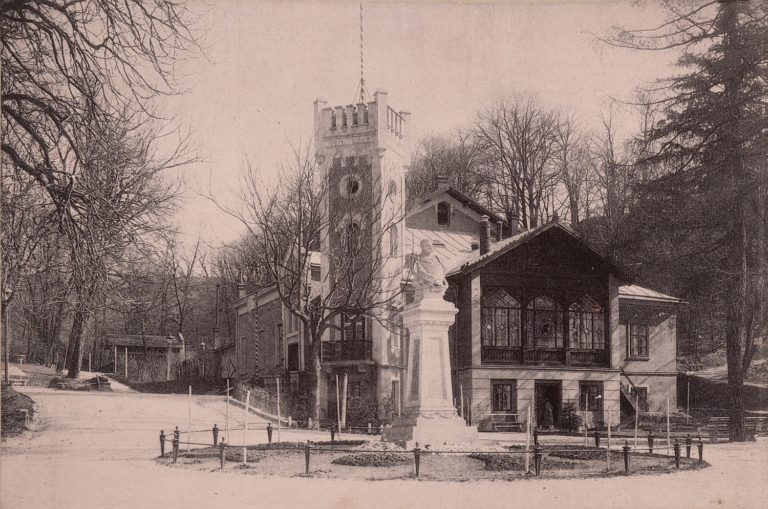

On the following day it became known that the senior three classes in the 1st Realschule were discharged. Only those who passed a new selection would continue to study there. The expelled school students gathered in the Stryiskyi Park for a meeting.

Obviously, the Polish and Ukrainian press had completely different explanations of what happened. According to the Dilo, the punishment of Polish students was too trivial. The newspaper also reminded that two Ukrainian students, detained on the day of the demonstration on the occasion of the "siege of Lviv by Khmelnytskyi", were expelled from school without the right of renewal. Allegedly, they had ended up there quite unintentionally. At the same time, the manifestations of Polish youth turned into open pogroms and beating of teachers, the punishment for this being only re-examinations. Polish newspapers justified "some violation of school rules" claiming that these were turbulent times, and young people were sincerely anxious about the future of the nation.

Youth and the Street Politics: "Going Wild" in the Era of National Confrontations

As a result of the Polish nationalists' activities in November, the Ukrainian national newspaper Dilo published several lengthy materials on the topic of the youth environment militarization. These materials should be taken with the same skepticism as the Polish press' news about "wild Haydamaks", but they convey the general mood of that time in a rather accurate way.

They criticize a practice widespread in the first years of the 20th century, when young people dressed in military uniforms began to be massively involved in the celebration of "fictional" anniversaries. This led to conflicts with school administrations as well as to fights and skirmishes with the police. According to the Ukrainians, local authorities treated young Poles and Ukrainians very differently. Polish schoolchildren, incited by nationalists, thus grew up with a sense of their own impunity, while Ukrainian schoolchildren felt resentment and hatred. That is, ideal conditions were created for national confrontation in the future. On the word of the Dilo, if the issue could not be resolved at the provincial level, dominated by the Poles, it had to be brought to the level of the parliament. To be precise, an action similar to the problem of the Ukrainian university was required.