Many of the mass events held by Ukrainians in Lviv during the period of autonomy were called viche (assembly). It was a kind of response to the numerous Polish demonstrations and historical celebrations. A viche could also be called to mark a historical date. For example, the First National Ruthenian Viche was organized on the anniversary of Emperor Joseph II, the "Liberator of Ruthenia," in 1880. There were also annual viches dedicated to the anniversaries of the abolition of corvee labor — the so-called freedom celebrations. The Polish administration blocked them as undesirable events, because they discussed "liberation from Polish slavery." While the Ukrainians criticized the Poles for "fictitious anniversaries," the Poles denounced the Ruthenian demonstrations as ideological indoctrination of ill-informed peasants.

This criticism was based on the fact that the idea of a viche at that time implied a certain form of behavior. In particular, there were supposed to be "delegates" authorized by someone to vote, as well as "speakers" and thus some kind of discussion or debate. Obviously, in conditions where several thousand people gathered at a viche, it is difficult to imagine dialogue or voting. Polish activists also blamed the Ukrainians for bringing peasants from all over Galicia to Lviv, while until the late nineteenth century only the organizers themselves represented the urban population.

The mass outdoor viches in Lviv were in fact political rallies. However, they still followed the "standard" list of attributes of a viche: several speakers, formal voting or approval, and the adoption of a resolution.

Peasant and "All-Nation" Viches in 1896

The peasant viche organized by the Radical Party activists on Sunday, November 15, 1896, in the City Council is a vivid example of what an ordinary viche looked like. It was called on the eve of the county council elections to be held in December. Another illustrative example is the viche organized by the Selianska Rada (Peasants' Council) Association, which took place in the Great Hall of the National House in December 1896. Delegates from 70 communities of Lviv, Vynnyky and Shchyrets counties took part in it. They decided to create a joint committee of Ukrainian, Polish and German peasants to nominate candidates from the peasants' curia.

Such events did not involve demonstrations, they did not mark public space, and they involved nothing more than discussions. Accordingly, they received little press coverage. It was rather the mass rallies (rather mechanically called viches) where it was technically impossible to hold any discussions or debates.

Ensuring that the Ukrainian mass events were truly massive was a major challenge for the organizers. Traditionally, parish priests were instrumental, leading "delegations" from their villages or carrying out local mobilization. Polish activists used this as an argument against the priests (whom they rather pejoratively called "popy") that they were deceiving the peasants ("chłopy") with politics.

Indeed, the support of the Greek Catholic Church ensured a larger number of participants. When Ukrainian politicians opposed the reform of the Basilian monastic order by the Jesuits (which began in 1882), seeing it as an act of Polonization of the "Ruthenian Church", they entered into a confrontation with church hierarchs, which directly affected the massive scale of their events. After the First and Second All-Ruthenian Viches in 1880 and 1883, which were really large, the "General Meeting of Ukrainians in Lviv" on May 4, 1884, or other "anti-Jesuit meetings" did not attract so many participants.

On October 11, 1888, the Fourth General Ruthenian Viche was held, as usual, in the National House. The reform of the Basilian Order was not the main topic, so many parish priests were present. The speakers spoke about the abolition of the propination laws (the nobility's monopoly on alcohol production), the economic situation of the peasantry, solidarity with Polish peasants, the use of the Ukrainian language in public service and education, and the need to create a joint electoral committee for national populists and Russophiles that would not cooperate with the Polish administration of the province. The speeches were accompanied by loud applause and shouts of approval. At the end the villagers present at the meeting were allowed to speak.

Ruthenian Assemblies in Lviv

Over time, the all-national viche format, which required extensive preparation, peasant mobilization, and overcoming the resistance of the Polish administration, receded into the background. Instead, Ukrainians increasingly held smaller but more dynamic political actions on topical issues. Sometimes they refused to hold all-national viches at all in favor of other events.

For example, on October 29, 1903, the Ukrainian deputies of the Galician Diet (Sejm) declared secession and demonstratively left the assembly hall because the majority of the Diet refused to open a Ruthenian gymnasium in Stanislawow. The very next day, October 30, a "meeting of Lviv Ruthenians" was held in the National House, attended by about 1000 people. On the one hand, there were deputies who explained their position, and on the other, "the whole of Ruthenian Lviv". After the meeting was over and the anthem "Shche ne vmerla Ukraina" was sung, some people, about 500, decided to march to the Diet building. Singing the song "Ne pora", they marched down ul. Trybunalska, through pl. Św. Ducha, but behind the Savings Bank on ul. Jagiełłońska, the police blocked the street. The demonstrators, shouting anti-Polish slogans, decided to go through ul. Karola Ludwika, Mariacki square and ul. Kopernika. However, there they again met a police cordon, a mounted unit coming from pl. Mariacki. Only thanks to the intervention of Andronyk Mohylnytskyi, a member of the Diet, the tension was broken and the people dispersed. In other words, it was a very modern political action for which local supporters were quickly mobilized and brought "to the streets".

40th Anniversary of the Prosvita Society

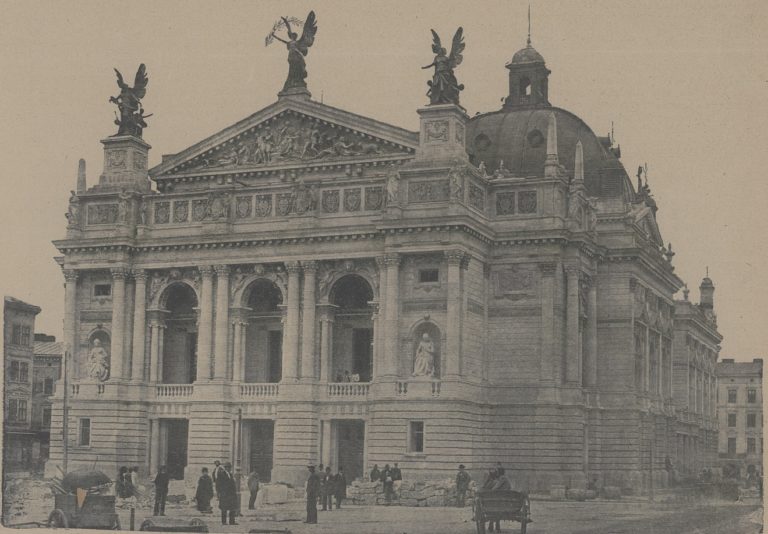

The idea of a national viche was abandoned when planning the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Prosvita Society, which was held on February 1-2, 1909. This was done to "save the peasants' money" and because there was no suitable hall. The National House, run by Russophiles, refused its premises, so the Ukrainophiles gathered in the building of the Yad Haruzim Jewish Society. In 1908 a number of festive evenings were held in the Society's branches throughout the region, while in Lviv it was decided to organize the anniversary in the form of a congress, with admission to the events.

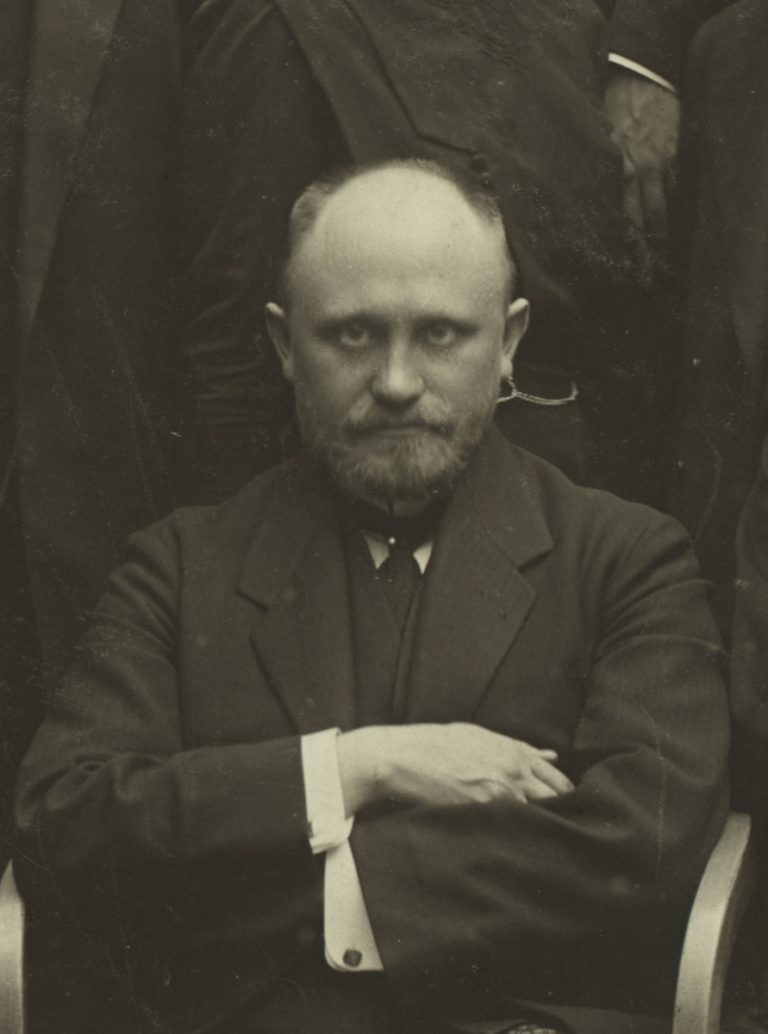

On 1-2 February 1909, "meetings" on education, cooperation, hygiene, economics, and a general meeting took place, opened by Yevhen Olesnytskyi, a member of Parliament. Festive concerts were held in the City Theater, where a performance and concert by the Bojan choir accompanied by a military band was held. The Sokil Society held an amateur performance in the building of the Yad Haruzim Society. Student festivities were organized at the Narodna Hostynnytsia (People's Hotel).

- Брошура до 40-ліття Просвіти / Brochure for the 40th anniversary of Prosvita

- Брошура до 40-ліття Просвіти / Brochure for the 40th anniversary of Prosvita

The ideological content of the events was, as always, eloquent. Lviv was interpreted as the "capital of Galician Rus-Ukraine" and the Prosvita society as the "mother of all Ukrainian societies." Accordingly, the congress was presented as a report on 40 years of national development. It is important that activists from Dnipro Ukraine attended the event, and the rhetoric of Galician activists resembled the theses of Polish politicians about gratitude to the Habsburgs for the opportunity to develop national culture, which was not available in the Russian Empire. They also talked about the need to open a Ukrainian university in Lviv and raised funds for a monument to Taras Shevchenko in Kyiv.

Meanwhile, the Russophiles did not limit themselves to refusing to rent the National House, but held a "meeting of men of trust" on that day. They appealed to the police to protect these meetings from possible provocations of the "Ukrainians" against the "russkiye" (i.e., Russophiles).

Growing Influence of Social Issues

The more Ukrainian events in Lviv became urban, without the participation of the peasantry, the more the card of social justice, workers' solidarity, etc. was played, and the less the clergy participated.

In May 1909, the Lvivska Rus Society gathered several hundred people, mostly workers and domestic servants, in the Yad Haruzim hall. Professor Oleksandr Kolessa, doctor Yevhen Ozarkevych, and deputies Ivan Kyveliuk and Volodymyr Bachynskyi spoke mainly about election fraud, Russophiles, the rights of the Ukrainian language, and education. But there were also speeches about taxation of workers and peasants, social protection, and electoral reform. There was a separate discussion about discrimination against Ukrainians in Lviv schools. After the meeting the participants marched to the building of the Prosvita Society on Rynok Square.

On September 29, 1909, two Ruthenian events took place simultaneously. In the National House, Russophiles gathered to discuss the state of affairs in the Mykhail Kachkovskyi Society. In the hall of Yad Haruzim the national populists discussed the electoral reform and the Russophiles. Later some of the populists decided to go "to the city", i.e. to the building of the Galician Diet, where a session was being held. On ul. Jagiełłońska, they were dispersed by the police. The demonstrators moved in small groups to the National House, where Russophiles were still gathering. From there they moved to the Prosvita building. Here, in Rynok Square, they were overtaken by police on horseback and on foot. Therefore, some of the demonstrators took refuge in the Prosvita building, while the rest retreated through ul. Blacharska, where they broke the windows of the Russophile Stavropegian Institute.

Several people were arrested and accused of organizing demonstrations during the Diet sessions. Minor clashes continued until 10:30 p.m., and police patrols were conducted until midnight.

In 1912, after the events at the university, tensions between Ukrainians and Poles were very high, and clashes with the police were not uncommon. Therefore, the mere suggestion of the Polish press that a Ukrainian demonstration would take place on May 16, 1912, the day of the abolition of corvee labor, mobilized both the police and Polish students. The latter actively protested against the possible opening of a Ukrainian university in Lviv. There was even a rumor that Ukrainians were collecting money to set up a charity fund named after Olena Sichynska, the "mother of Andrzej Potocki's murderer". However, these worries were groundless and nothing much happened.

* * *

Interestingly, despite the striking changes that took place in Ukrainian demonstrations during the period of autonomy, these events continued to be called viche. Although the transformation from the gatherings of "peasants and priests" in the 1880s to street confrontations and clashes with the police at the beginning of the 20th century was enormous. Modern political actions were becoming more common, as quick reactions and the ability to create a newsworthy event to make the headlines were important in politics. In addition, the controversy between Russophiles and the national populists, as well as the resistance of local authorities, added to the dynamics. Moreover, the greater the contradictions with the Russophiles, the more the populists cooperated with Jewish organizations.

At the same time, the general viche did not disappear as an idea, so massive public meetings were held from time to time. During these events, political activists were forced to seek help, or at least moral support, from the Greek Catholic clergy.