During the "long 19th century", beginning from the time of the French Revolution, the concept of "citizenship" spread massively in Europe. Governments and rulers sought to secure the loyalty of a wide range of citizens and subjects using the methods available at the time. In addition to the press, the spaces of cities, where the government directly appealed to the population, became very important. On the other hand, these spaces became places for manifestations and representation of citizens, where they "spoke" to the authorities.

Lviv was no exception. Moreover, in the last third of the 19th century, after gaining autonomy, it all was even more interesting here. The presence of three main population groups: the Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians, as well as competition between the Poles and Ukrainians for Lviv as the capital city for their national projects, was felt quite well. The Poles tried to emphasize the "Polish nature" of Lviv, while the Ukrainians and Jews attempted at least at showing their presence in the city.

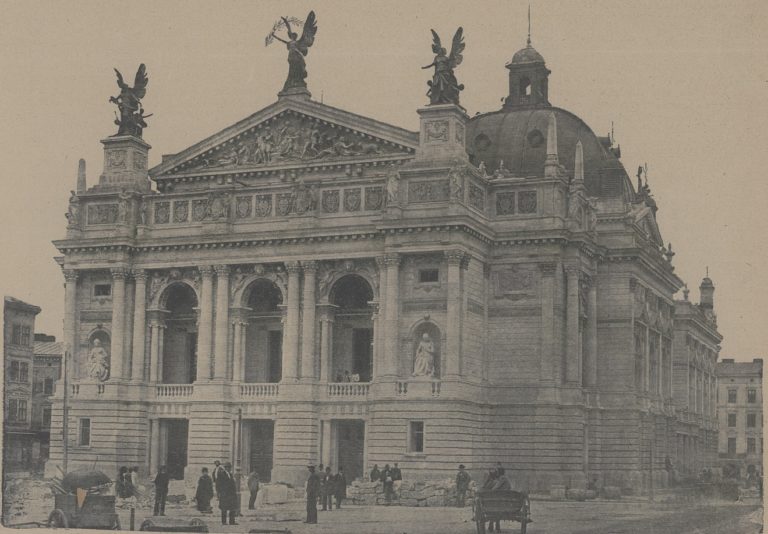

Consequently, different interpretations of the same spaces and objects appeared: what was the "City Theater" for some, was at the same time yet "another Polish institution on our Ukrainian soil" for others.

At the time of mass politics, when the suffrage covered an ever-increasing share of the population, city squares, spaces and objects available there were attributed a new function. They became a place for regular meetings and demonstrations. Most of the marches ended near the City Theater or the monument to Adam Mickiewicz, rallies were often organized there. In contrast to the "good old" times, when one could celebrate in the church and at the Strzelnica (Shooting Range), mass politics brought people to the streets, without confining them to institutions or clubs.

Mass politics influenced not only using the city’s space but also building it. Lviv was considered the capital of a crown land and, in addition, the capital of two national projects, so it should have appropriate buildings and monuments, while streets should have the correct names.

In the last third of the 19th century, unique conditions were formed in Lviv. The population growth, the increase in the bourgeoisie’s influence, the formation of new centers of power due to autonomy overlapped in time with the growth of the Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish national movements. This led to a turbulent process of renaming, rethinking, construction and exploitation of urban space.

Monuments

In the second half of the 19th century, after the granting of autonomy, Polish monuments began to appear in Lviv en masse. At first, these were purely religious things, such as sculptures. However, apart from being positioned as Catholic and therefore Polish, they also had an additional, purely national significance. Thus, in 1861, the column of St. John of Dukla was restored in front of the Bernardine church with the inscription reading as follows: "The city of Lviv, miraculously freed from the siege of Bohdan Khmelnytsky and Tuganbey, Khan of the Tatars, by the hand of the blessed John of Dukla in 1648."

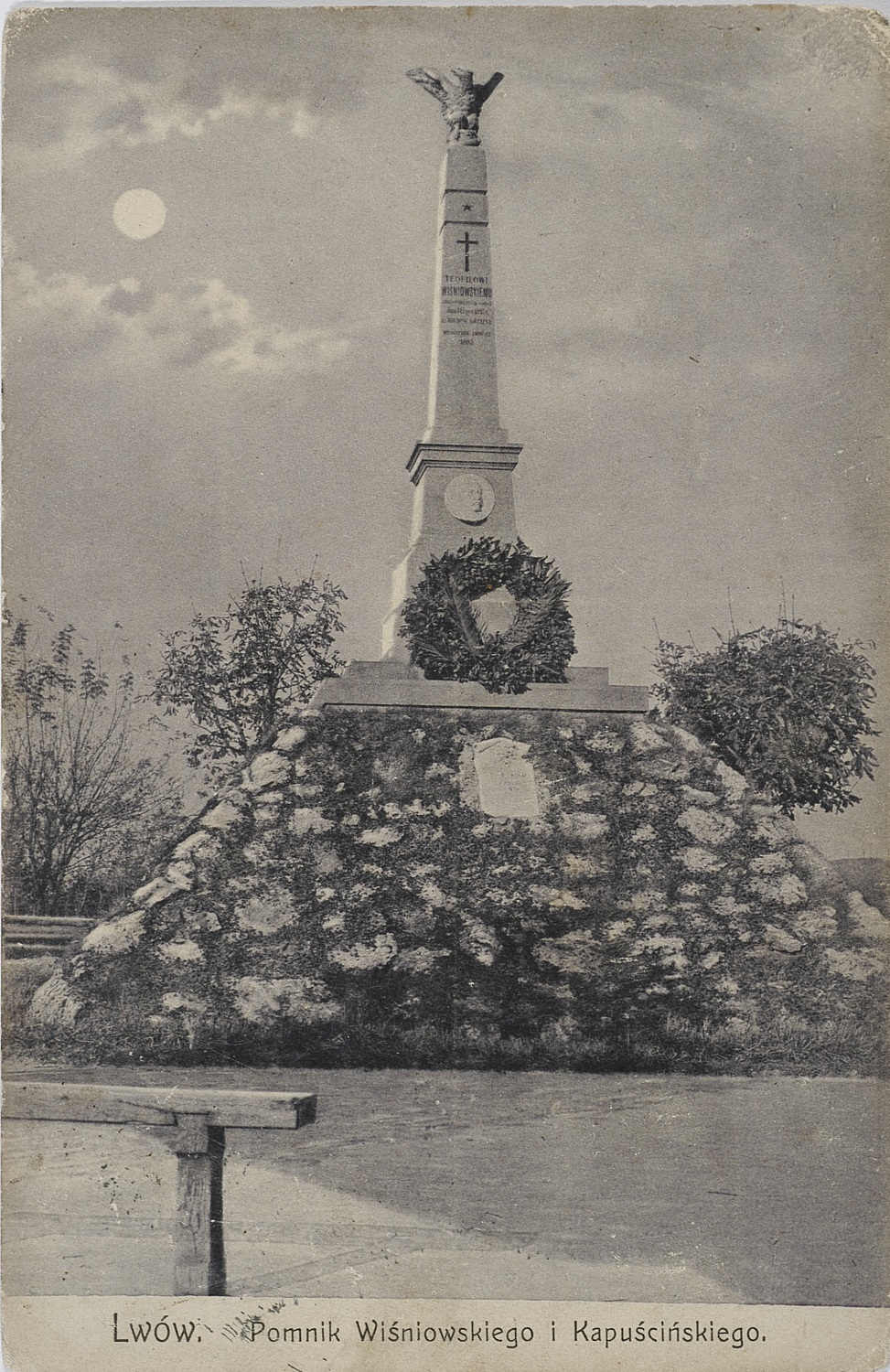

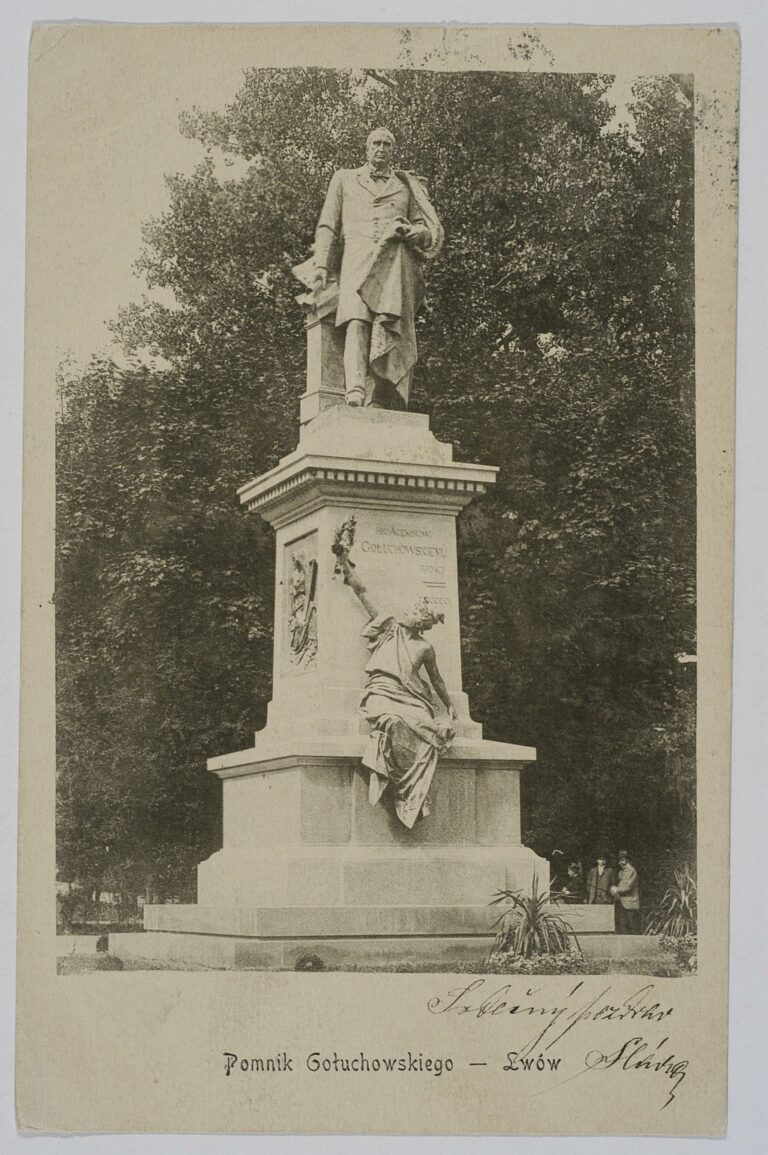

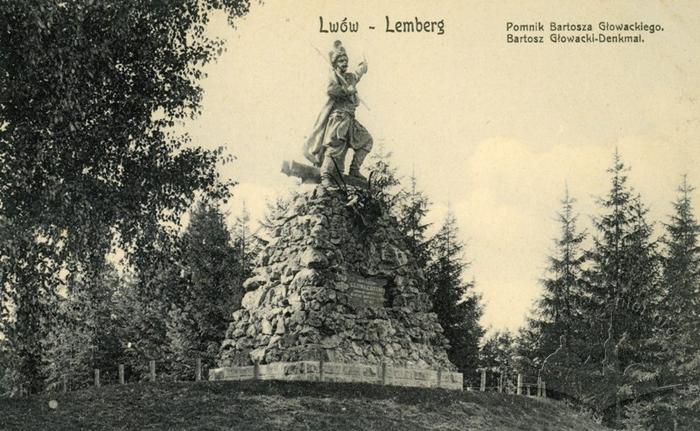

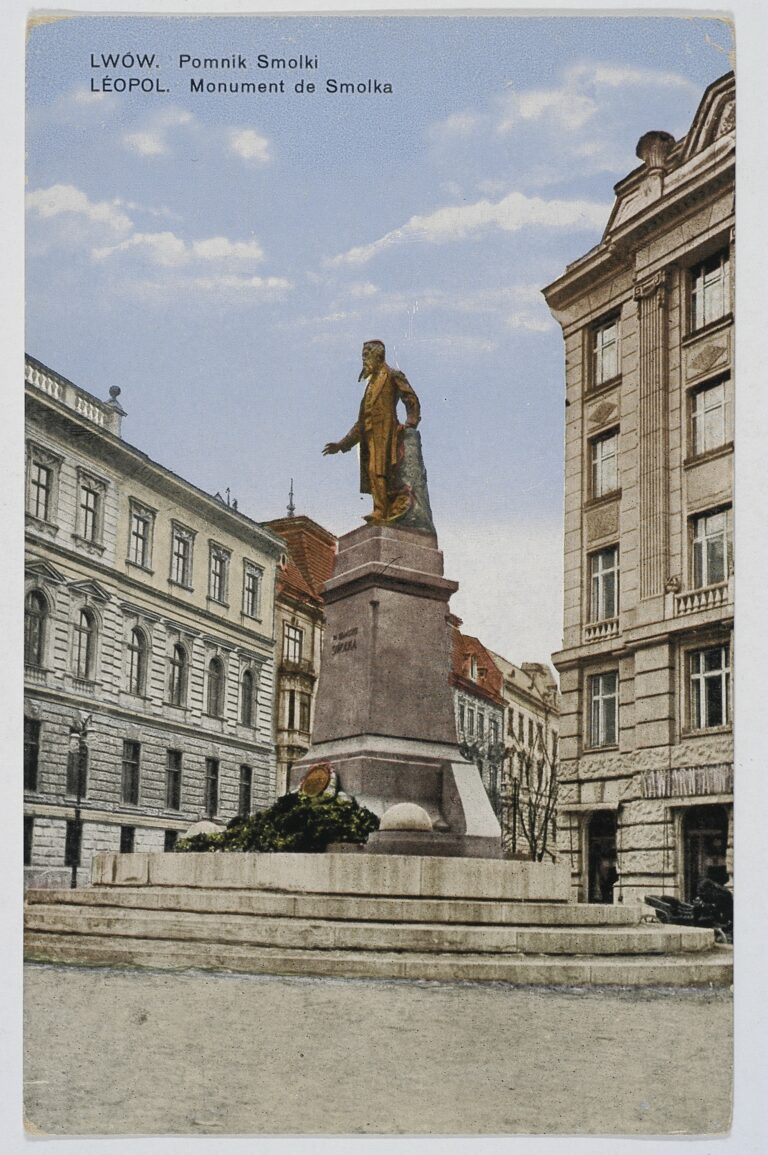

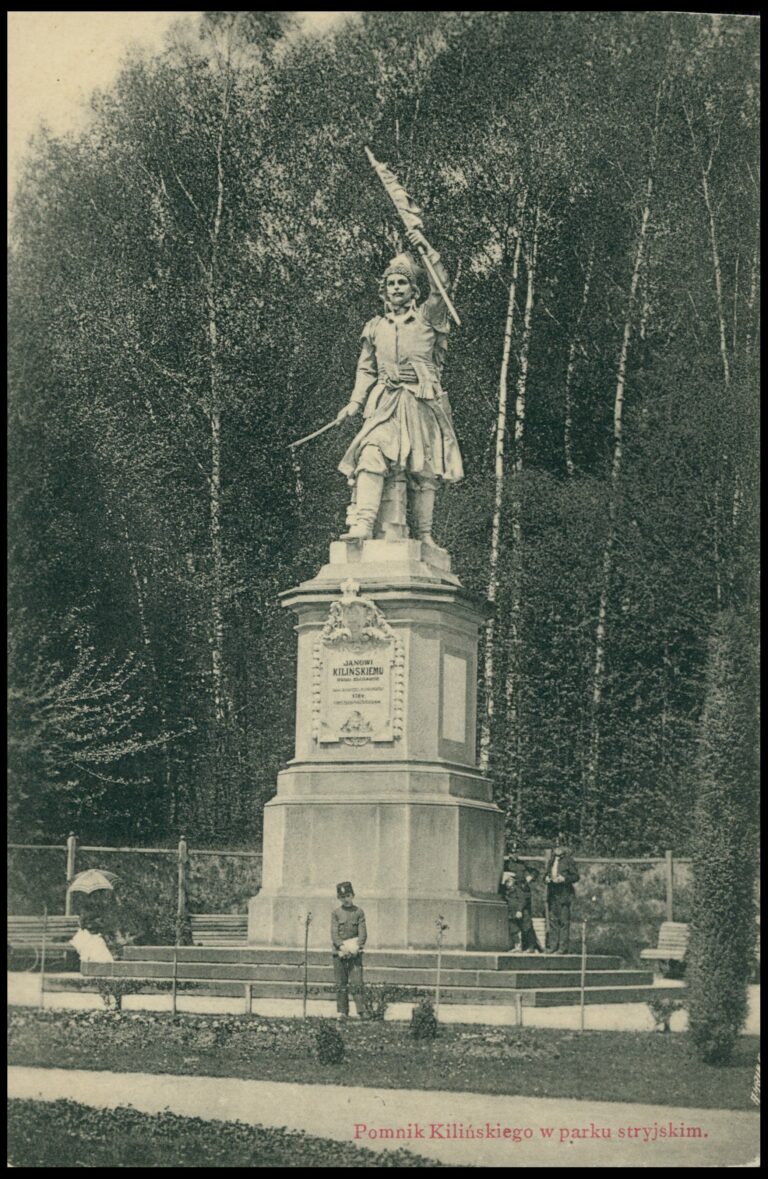

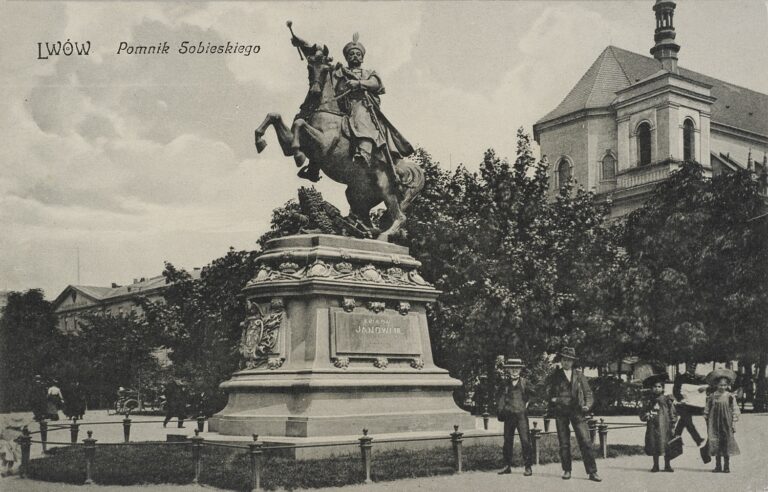

At the turn of the 20th century, there was a surge in the installation of monuments in the modern sense: to Jan III Sobieski, Jan Kiliński, Teofil Wiśniowski and Józef Kapuściński, Aleksander Fredro, Kornel Ujejski, Agenor Gołuchowski, Bartosz Głowacki, Franciszek Smolka, or Adam Mickiewicz. There were also numerous plaques, busts, and halls named in honour of various distinguished figures, it all filled with the right ideological content. Massive marking of public space and its instrumentalization for political purposes took place.

The Ukrainians also tried to take part in a similar process, in particular, to erect a monument in honour of Taras Shevchenko. When the Shevchenko Scientific Society purchased a building on Wały Gubernatorskie (now Vynnychenka Street), Ukrainian politicians tried to lobby for this monument to be erected in front of this building. However, opposition from the Polish city authorities did not allow this to be done. Before the First World War, Ukrainians were able to put up a bust of Shevchenko in the town of Vynnyky and a memorial stone sign in the village of Lysynychi near Lviv, but not in Lviv itself.

Buildings

With buildings, it was easier. Firstly, it was a matter of private property, not public space. Secondly, the Austrian authorities tolerated manifestations of the subject peoples’ national development, such as the opening of schools, society halls, and the like.

Of course, the Poles had more opportunities in this area as well, since they not only owned an extensive network of real estate like the Strzelnica but also, having the city government at their disposal, used theoretically "city-wide" objects, such as the City Theater, for their national project.

However, when the Ukrainians or Jews built something of their own, they could give the new building such an appearance that would clearly indicate its national affiliation and would make it a kind of monument affecting the public space and changing it. Like, for example, the building of the Dnister society, designed in a "folk style", with heraldic signs like historical coats of arms of the Ruthenian Voivodeship and the city of Kyiv on the façade.

Nevertheless, the city's main public buildings and symbols worked for the Polish national project, while the Ukrainian or Jewish ones increasingly turned into national enclaves, islands of "their own" in the middle of the Polish city, whose highest point was the Mound of the Union of Lublin at the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) Hill.

Streets

To this should be added the renaming and naming of streets and squares, which acquired a distinct Polish national character during the Habsburg autonomy. Although Ukrainian names, if compared with Jewish ones, were more numerous relative to the proportions of the population, the streets with Ukrainian names were located on the periphery and did not have any key role in the central part of the city.

Mykhailo Hrushevskyi wrote that Szewczenko Street in Lviv was a small, unpaved street on the outskirts of the city, in the neighbourhood of Pohulianka, rightly called Błotna (Boggy) Street before. Its only sign was written in Polish and nailed to one of the houses.

Thus, when politics and everything related to it, including various celebrations, "went to the streets", these streets, public buildings and symbols were or were becoming Polish.

* * *

How exactly the three national groups marked the space can be seen in three not-so-famous but quite revealing examples.

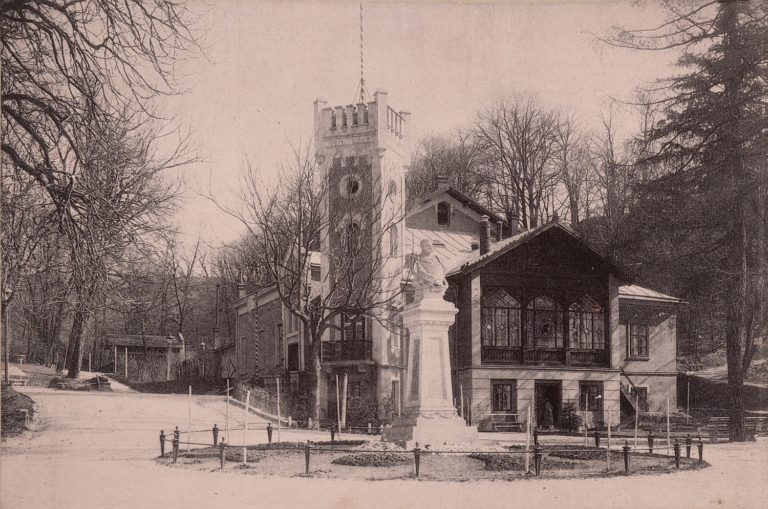

I. The installation of the bust of Michał Michalski at the Strzelnica on September 29, 1909 was, on the one hand, a private affair of the Rifle Association. On the other hand, Michał Michalski was not only the former chairman of this association but also one of the most popular presidents of Lviv, so the case acquired a city-wide significance. The event itself seemed quite private as only the widow and members of the Rifle Association were present. However, since this association united the most prominent politicians of that time, the bust was actually opened by well-known deputies and the then president of the city, Stanisław Ciuchciński.

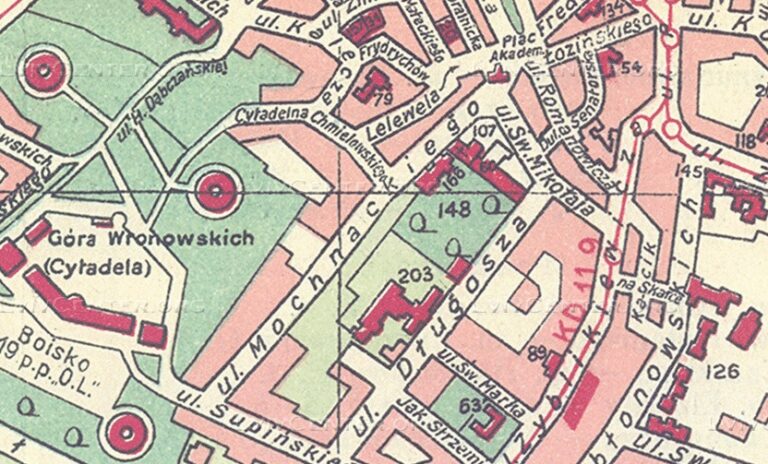

II. On December 13, 1913, the name day of the founder, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, in a specially purchased villa at Mochnackiego 42 Street (now Drahomanova Street) an institution called "National Museum. The Jubilee Scientific Foundation of the Metropolitan of Halych, Andrey Sheptytsky" was handed over "as a gift to the Ukrainian people" and opened to visitors. This event confirmed two typical things of that time. Firstly, the museum was handed over to the "Ukrainian people", without mentioning the "city" or "community", thus proving once again that Ukrainian institutions in Lviv were rather national enclaves. Secondly, despite the efforts of politicians and secular intelligentsia, the role of the Greek Catholic Church in Ukrainian politics remained a key one.

III. In 1909, as part of the celebration of the 115th anniversary of the victory of Tadeusz Kosciuszko near Racławice, the city authorities renamed one of the streets in the Jewish quarter in honour of Berek Joselewicz, a participant in the Polish uprising (this also coincided with the anniversary of his death). A special memorial plaque in his honour was also opened there, as though setting in that way the standard of a "correct Jew", who had to be a political Pole and, even better, an active participant in the Polish struggle for independence.

Thus, a Polish object, even if it was private, turned into a city-wide and often a national object. A Ukrainian object, even if it was called "national", did not become city-wide but remained part of the national enclave. A Jewish object could become city-wide turning into a Polish one.

It was even more interesting when the public space became not just an object of competition between national projects but a place of a conflict between them, especially when such an object was far enough from the center of the city and without appropriate supervision by the police.

Thus, in 1909, during the same celebration of the 115th anniversary of Kosciuszko's victory, a memorial plaque in honour of Kosciuszko and Głowacki, as well as a cross in memory of the May 3 Constitution, was erected at the Devil's Rocks near Lviv. The plaques were shortly destroyed by three Ukrainians, residents of the nearby village of Lysynychi. In court, it was not possible to prove the national or political motives of the vandals, but the case was an irritant and a reminder for a long time.

The Polish press traditionally described this incident as "Haydamak savagery". Since the case was clearly not in favour of the Ukrainian movement (the vandalism was proven in court after all), the Ukrainian press decided to "dig" deeper and to investigate the reasons behind this act of vandalism.

According to the Ukrainians, the Poles were engaged in "decorating the Ruthenian land with Polish symbols": Mickiewicz oaks, crosses dedicated to Polish insurgents, monuments, chapels, and statues of the Mother of God, the Queen of the Polish Crown. The Ukrainians also remembered the case when in 1907 Polish activists stole the bust of Shevchenko in Vynnyky and threw it into the Sobko pond, as well as the reluctance of the City Council to allow the installation of a monument to Shevchenko in principle. Therefore, Ukrainian politicians interpreted the actions of Ukrainian vandals as a natural reaction of the oppressed people. That is, the Ukrainians not only noticed the active marking of space by the Poles but also did not protest against it. Thus, the marking process itself became the object of controversy between national projects.

* * *

Therefore, the public space of that time is not only about the environment, which spoke through monuments, tables, inscriptions, etc., but also about the place where the action of political activists was possible. Consequently, the opening, presentation or consecration of the space is like an invitation to its "use", which was actively exploited by political activists. Polish politicians mainly exploited the Mickiewicz monument, the City Theater, the Rynok Square, the Hill of Executions, while Ukrainian politicians exploited St. George's Square and the People's House. The Vysoky Zamok Hill and the Lychakivsky cemetery can be described as common or disputed territories.

With the development of the gymnastic movement in Lviv, the corresponding infrastructure was also built: stadiums and Sokół/Sokil houses, which also worked for the "national cause."