The period of Habsburg autonomy was a time of emancipation, when various population groups became "visible", obtaining at least the opportunity to "speak out" at rallies and demonstrations, to sign a petition or to discuss a draft law, if not the right to vote in the modern sense of the word. This was a time, when not only nationalism was spreading but also socialist ideas, which in Austria-Hungary, where the interests of different peoples had to be reconciled, took shape in a specific type of socialism, Austro-Marxism, whose followers paid considerable attention to the national issue itself.

Emancipation processes allowed various national communities to "come onto the stage"; the government was now formed not only by aristocrats but also by representatives of bourgeoisie; in addition, manifestations of workers and women became frequent as both were becoming organized groups with their own subjectivity.

Workers

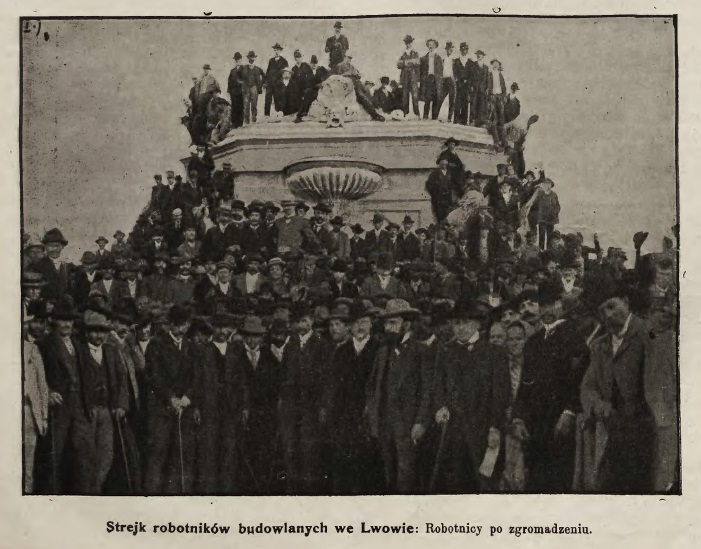

Lviv had never been a working center, as there was no developed industry there. Nevertheless, the city had a certain number of workers, whose political activism was visible, mostly in cases where they coordinated their actions with students and left-wing politicians. Moreover, it was the city where the authorities of the entire province were located, as well as editorial offices of influential newspapers; a lot of politicians and officials also lived in Lviv, making the city an important center of political life.

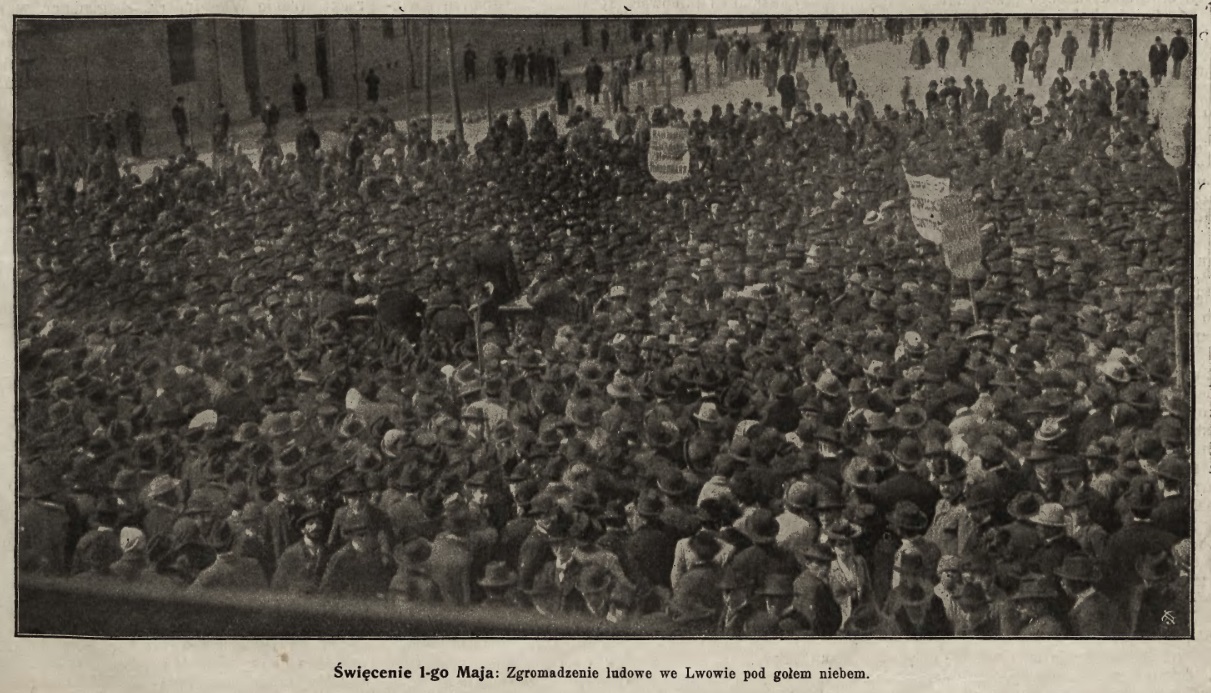

Therefore, workers' actions in their pure form were never sufficiently massive unless other groups joined them. The May Day demonstrations were mostly quiet and peaceful. On the other hand, when the national was added to the social — for example, solidarity with the insurgent workers of Warsaw — there were serious riots and mass protests in the city sometimes.

The socialist movement leaders represented all three of the province’s largest national groups, and for a long time, almost until the Great War itself, there were no national conflicts between them. There were misunderstandings between Christian and Jewish organizations, there were accusations of "venality" and "internationalism" by nationalist politicians. However, there was nothing strange in the fact that a Ukrainian socialist spoke at the grave of a Jewish worker. As a rule, class solidarity, at least in rhetoric, prevailed over national solidarity.

Examples of workers' demonstrations in Lviv during the times of autonomy demonstrate many interesting things that cannot be seen through the prism of purely "national history", for example, the fact that there were real conflicts between highly skilled and low-skilled workers (so-called "foremen" and "journeymen"). These conflicts nullified business attempts to "revive guild solidarity." It turned out that workers were not willing to work for minimum wage, even if it was considered patriotic. At the same time, the workers were ready to get rid of competitors from other cities under the same pretext: to protect the interests of "Lvivians" by not allowing newcomers to the local labour market.

Another interesting aspect was the role of socialist politicians in the workers’ movement. The history of workers’ strikes shows that politicians always tried to mediate between workers and employers. Moreover, they sought both to obtain political dividends and not to be arrested on charges of incitement. They often failed to control the crowd, and workers' demonstrations turned into bloody riots.

The course of workers’ demonstrations shows the difficult relations in the triangle "Poles-Ukrainians-Jews", both at the level of "Christians-Jews" and at the level of the Ukrainian-Polish confrontation, as well as the fight between nationalist and socialist politicians for the same electorate. As a result, socialists were forced to appeal to national feelings, while nationalists had to appeal to the problems of social injustice.

Also, "another geography" of Lviv can be seen through workers' demonstrations. Unlike imperial visits, religious festivities or national manifestations, the workers' Lviv was not only a square in city’s center but also the city’s periphery, where, as a rule, everything initiated.

Women

The situation with women's emancipation was similar. For a very long time, women did not act as a separate entity at all, and the women's movement in Habsburg Lviv developed on a national basis. One of the first notable actions, when women manifested their "political existence" not indoors but in the public space of the city, was the Women's Day in 1912, organized by the socialist party throughout the empire. However, even at this action, like at previous chamber events, about half of the participants were male politicians, who had their own plans for women as agitators on the eve of the elections. Mostly women's associations and organizations were a kind of "auxiliary units" of national communities.

In the end, the tendencies, when the labour and social issues were subordinated to those national, finally prevailed during the Great War and the subsequent Ukrainian-Polish war. Faced with a choice between social and national solidarity, workers and women chose the latter.