The 1st of May as the Workers' Solidarity Day began to be celebrated in Lviv simultaneously with the cities of Western Europe and America: in 1890. This date was determined by the congress of the Second International in memory of the mass protests of workers for the 8-hour working day, which took place in the USA in 1886.

Before, the pagan feast of the "return of spring" was celebrated in Lviv, as in many parts of the continent, on this day. Traditionally, a military chapel choir held a so-called "awakening" on the streets of the city center, which was actually dedicated to "the first day of May." From 1890, the emphasis changed.

The local peculiarity was that Lviv was not an industrial center with a large number of proletariat. It was, however, an important center for three peoples: Polish, Jewish and Ukrainian. For the Poles and Ukrainians, it was also an important symbol around which national projects were built. Therefore, the national issue in Lviv was never inferior to the social issue in terms of importance or relevance.

For example, on May 1, 1905, Polish workers not so much fought for their rights as demonstrated solidarity with the Poles of the Kingdom of Poland, victims of Russian repression. The proximity of another important date, the Third May Constitution Day, made itself felt too, reducing social and labour issues in importance and actualizing the ideas of an independent Poland instead.

May 1, 1890: the beginning of a tradition

The day before, the Austrian authorities officially approved a day off and allowed demonstrations. However, in practice, workers had to agree on their absence from work with their employers. Otherwise, it was considered a violation of the employment contract.

In addition, as early as 1890, simultaneously with the idea of a unified workers' holiday, there was an idea to shift its celebration in Lviv to May 3, the Constitution Day. Immediately, a division between "patriots" and "internationalists" arose among Polish activists, who saw the role of workers in the future "struggle" in different ways. Supporters of the May 3 celebration accused the "internationalists" of "sowing the seeds of discord" and splitting the patriotic community.

Expectations for the first May Day rally in 1890 were not trivial. There were rumours of future pogroms and looting, shop owners decided not to work on that day just in case, the military garrison was prepared to disperse the demonstrators. However, the reality turned out to be more ordinary. The City Council allowed the workers to hold a demonstration in the City Hall's courtyard. Not only "radical elements" took part in it but also associations and societies that usually took part in patriotic demonstrations (such as the Society of Polish Workers and Industrialists Gwiazda).

After that, workers near the City Hall often ended their meetings with the shouts of "Long live!" (pol. Niech żyje!) addressed to the presidents of the city of Lviv — for permission to hold rallies in the courtyard. Ironically, the City Council consisted mainly of industrialists and entrepreneurs, owners of factories and workshops, that is, supposedly, the class enemies of those whom they allowed to manifest on May 1 within the City Council walls.

Nothing revolutionary: the course of May Day celebrations

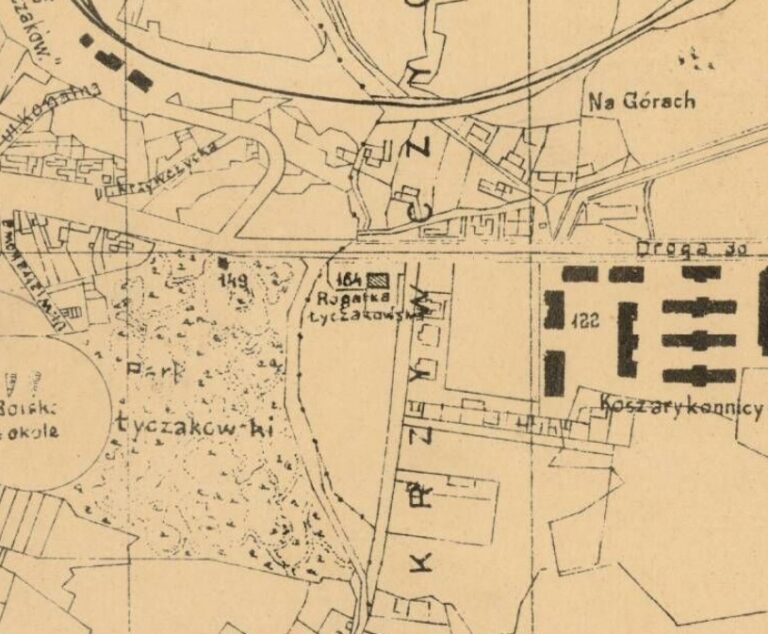

Over time, as sentiment among workers became a factor influencing elections, the festivity became more respectable and more numerous. The participants could no longer fit in the City Hall courtyard, so they chose other locations. The workers moved their evening outdoor fetes to the post-exhibition area or held them at the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) Hill or in the neighbouring villages of Pasiky or Lysynychi.

May Day was an opportunity for social democratic politicians to remind everyone of themselves, to talk about the 8-hour working day, universal secret equal suffrage, insurance, restrictions on women's and children's labour as well as about disarmament and peace in the whole world. There was nothing revolutionary in these rallies. After all, the police were always on the alert, and this should have affected the demonstrators' mood as well.

Nationally oriented politicians criticized this holiday, going so far as to use derogatory anti-Semitic wordings like "gathering of socialists and Jews." Ukrainian populists, for example, generally denied the idea of "proletarians of all countries, unite" as unfeasible and manipulative, asserting that in Galicia it became a tool of the "polonization of Ukrainian workers." Polish nationalists claimed that the constitution of May 3, adopted during the time of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, settled relations with workers a long time ago. After all, for the local elite, who controlled the City Council and belonged to the milieu of local entrepreneurs and acknowledged patriotic leaders (the so-called Strzelnica), leftists were ordinary political competitors, so they fought the latter, attracting workers through patriotism and thus shifting social issues to the background.

In general, the scenario of each action was typical of a demonstration in Lviv at the turn of the century: a rally, speeches, singing workers' songs and anthems; eventually, a march through the city streets and a recreational programme in the evening were added.

We can imagine the celebration geography in the city space with the help of a short chronological presentation of individual (not all) celebrations.

In 1895, workers held a rally on pl. Franciszkański, near the building of the Gwiazda association.

In 1896, about 2,000 people, their absence agreed with their employers, gathered at 10:00 a.m. in the Music Hall in the post-exhibition area. Then the participants went on a march through the streets of the city, accompanied by a police unit. Another rally, in support of universal suffrage, was held in front of the Diet. The newspaper Dilo, which carefully monitored the use of the Ukrainian language at the events organized by social democrats, reported that "some spoke Ruthenian with Jewish jargon" ("jargon" meant Yiddish — note). In the afternoon, the workers gathered for entertainment behind the Lychakivska turnpike, but heavy rain and hail did not allow them to finish the celebration, so the participants returned to the city as early as 6 p.m.

In 1898, the participants wearing red cockades rallied on pl. Strzelecki. After that, they marched to the Hausman passage with banners reading "Long live social democracy!", "Long live May 1!"

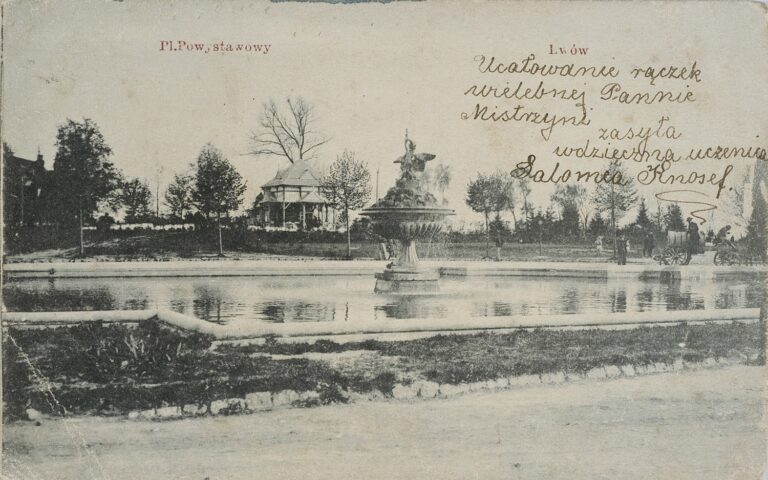

In 1900, a rally was held in the post-exhibition area in the Stryiskyi Park.

In 1901, a rally was held on pl. Strzelecki and a march from there to ul. Sykstuska (now vul. Doroshenka 17) to the premises of the Workers' Association Syla.

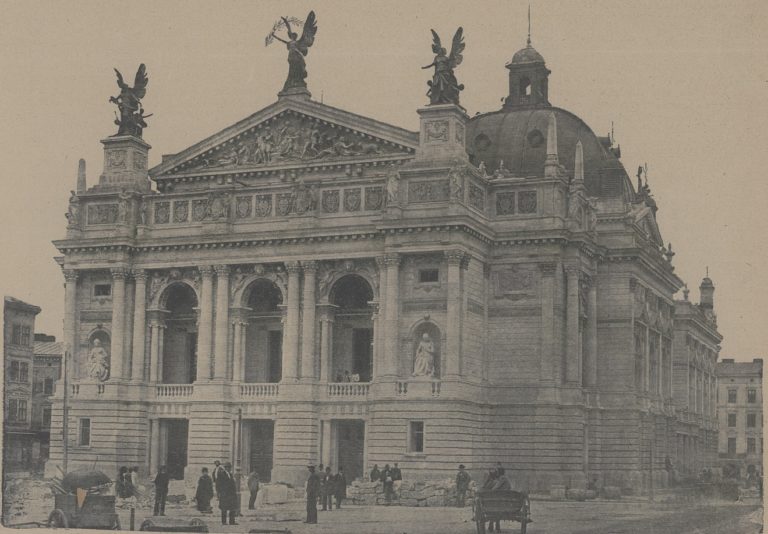

1905 was a year of the revolution in the Russian Empire. In Lviv, it was also full of protests, demonstrations and conflicts. In spite of public fears, however, nothing extraordinary happened on May 1. The workers built a platform on pl. Gosiewskiego (now part of vul. Tershakovtsiv), marched past the Adam Mickiewicz monument to the City Theater and held an outdoor fete at the Vysoky Zamok Hill in the evening. The only difference from the usual May Day was expressions of solidarity with striking workers in the Russian Empire.

In 1907, two rallies were held simultaneously. Polish and Ukrainian workers gathered on pl. Gosiewskiego, while Jewish workers gathered on pl. Zbożowy (the territory of the old Jewish suburban neighborhood, now Zernova Sq.). Although it was raining, the Ukrainians and Poles marched to the City Theater, where they sang the "Marseillaise" and listened to speeches. The Jewish workers marched from pl. Zbożowy to ul. Wały Hetmańskie and gathered in front of the Industrial Museum (arriving at the City Theater shortly after the previous demonstration). In the afternoon there was a special performance at the City Theater, followed by a party with dances at the Belle Vue Hotel in the evening.

In 1909, similarly, two rallies took place. After the rally on pl. Gosiewskiego, the Poles and Ukrainians marched to the City Theater. A performance was held in the theater, followed by an outdoor party in the post-exhibition area in the evening.

In 1912, rallies were held on pl. Gosiewskiego and pl. Zbożowy again. After their assembly's resolutions were read, Jewish workers marched through the city to join the rally of Polish and Ukrainian workers. At 11:00 a.m., they held a joint meeting on pl. Gosiewskiego, after which they all marched together to the City Theater.

Over time, the celebration of May Day became just one of public policy elements. There were no riots, pogroms or skirmishes that the townspeople were threatened with in 1890 (usually, all this accompanied celebrations in many other European cities). Instead, there were performances in the City Theater and parties with dances in hotels or outdoor fetes.

The national question, as mentioned above, always remained in the foreground. The organizers and participants diligently followed the unwritten rule to use the Ukrainian language, albeit in a very limited amount, in speeches and songs or on banners. This allowed the Polish and Ukrainian social democrats to maintain at least an outward monolithic unity. Instead, Jewish workers eventually began to celebrate independently and were criticized as "separatists." On the other hand, Ukrainian populists set Jewish workers as an example for the Ukrainians. After all, they managed to manifest their own national separateness and political position without joining the actually Polish socialist movement.

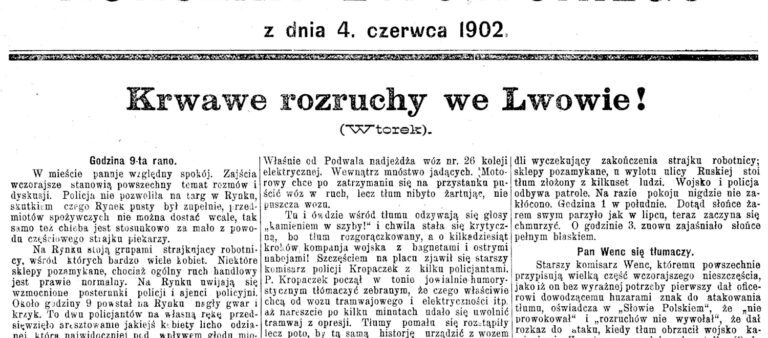

In general, workers' demonstrations that took place in Lviv during the autonomy period are more illustrative and interesting on other occasions than May 1, in cases when they happened spontaneously or as a response to the challenges of time.