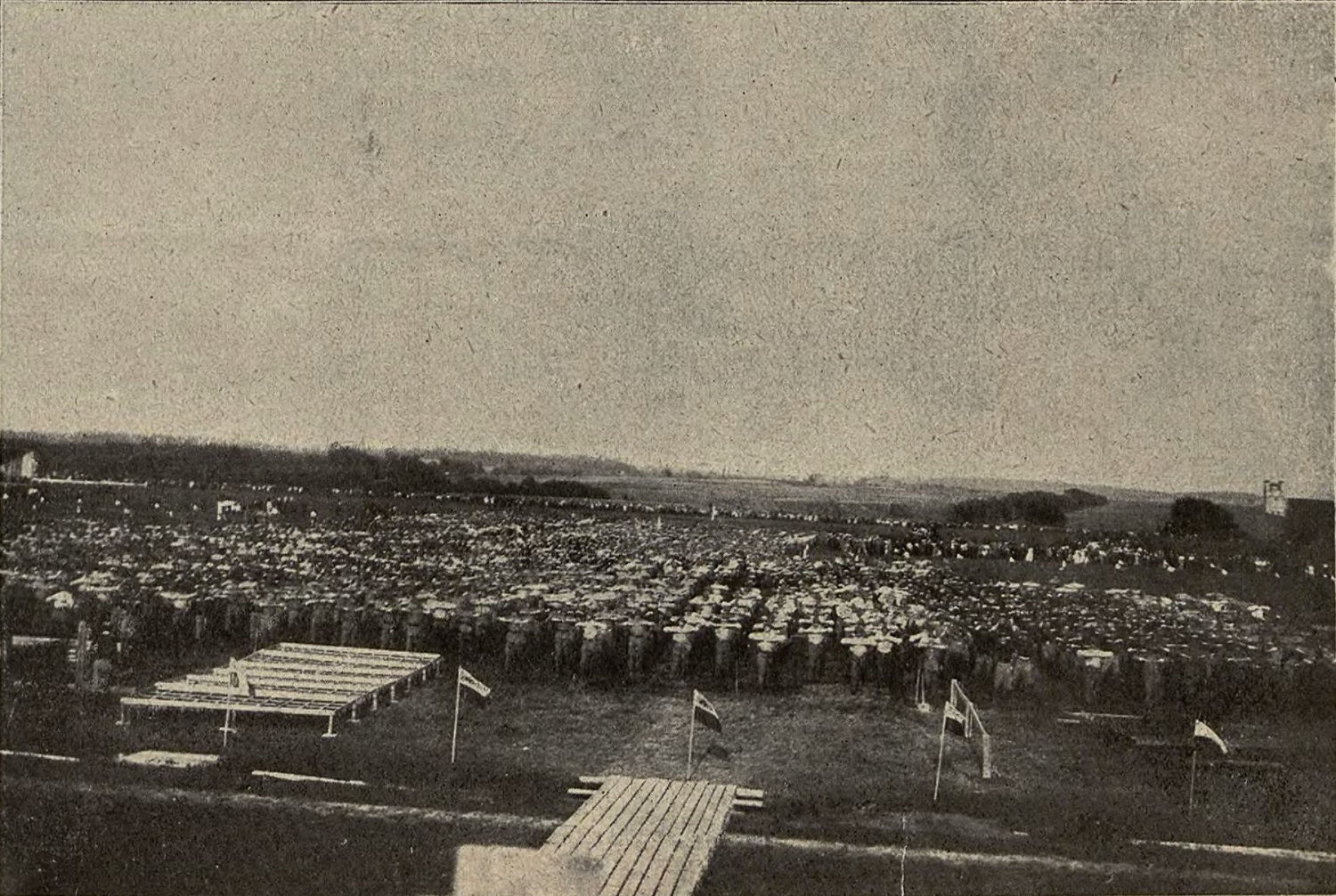

In 1913, Lviv hosted not just a regular Sokół's rally, but a real military demonstration. On the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the January Uprising, more than 8,000 armed and equipped members of the gymnastic society and scouts held a "training" on the topic of "the battle for Lviv against the Russian army". This, against the backdrop of deteriorating international relations, wars in the Balkans, and the expectation of new conflicts, was a serious claim for the future armed struggle.

The course of the event

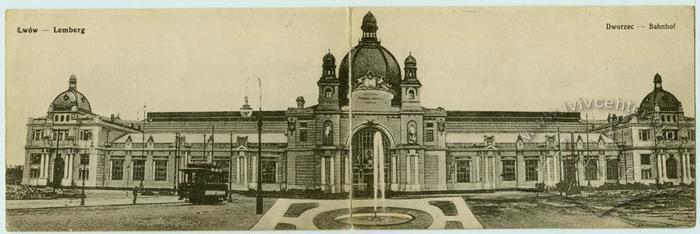

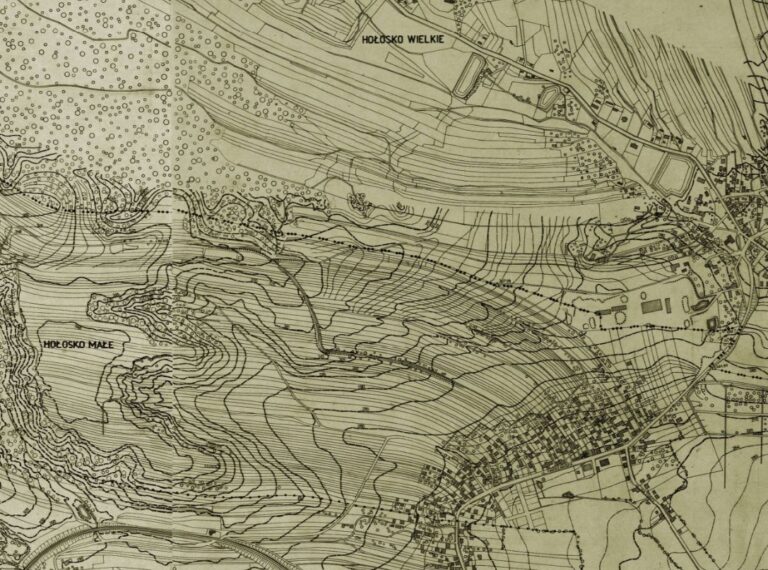

On the night of 6 July, about 7,500 participants arrived by ten specially ordered trains in Lviv, at the main station and the Pidzamche station. In the rain, at night, they marched to the northern outskirts of the city — to Zamarstyniv, Holosko, and Hrybovychi.

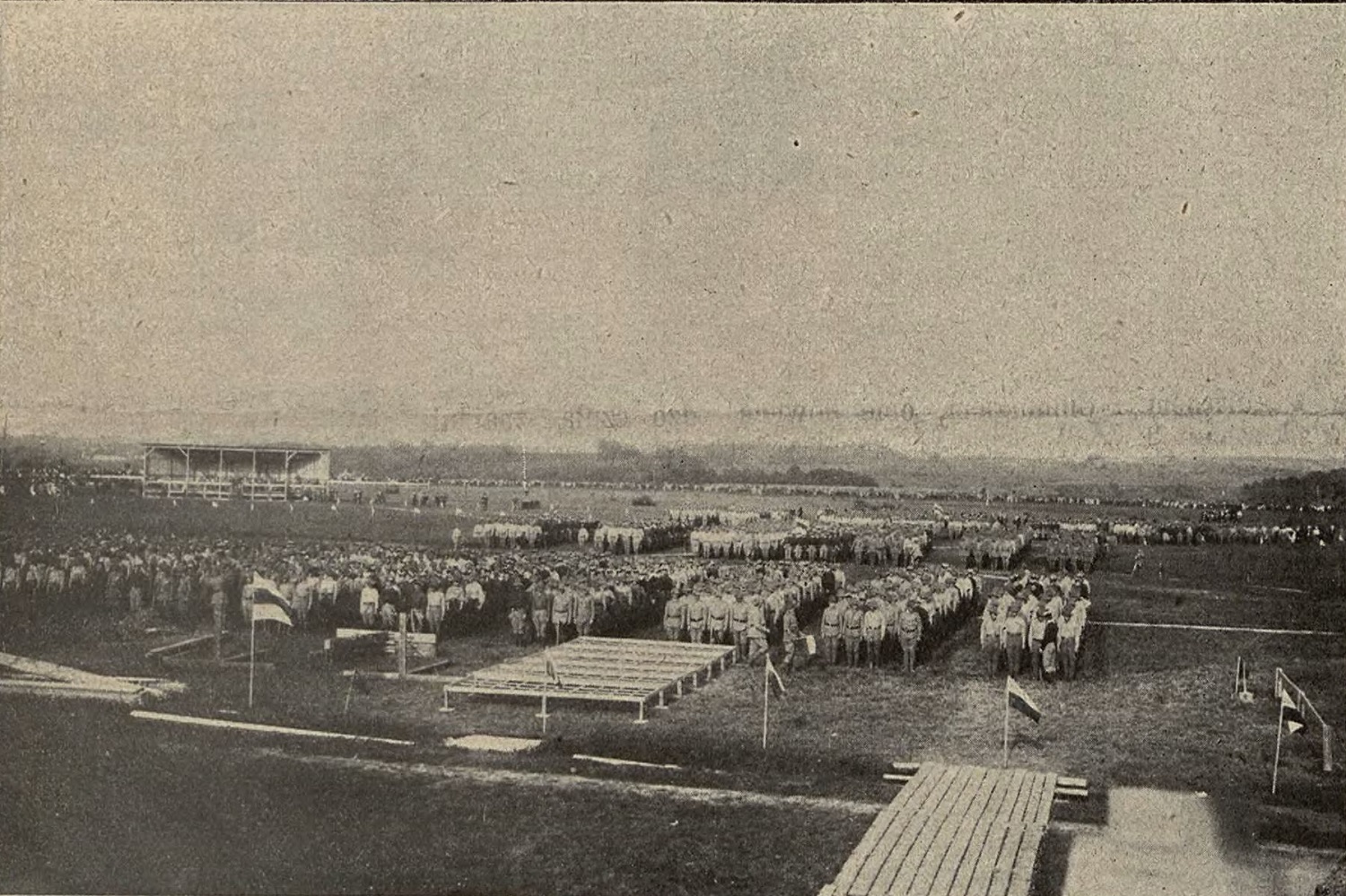

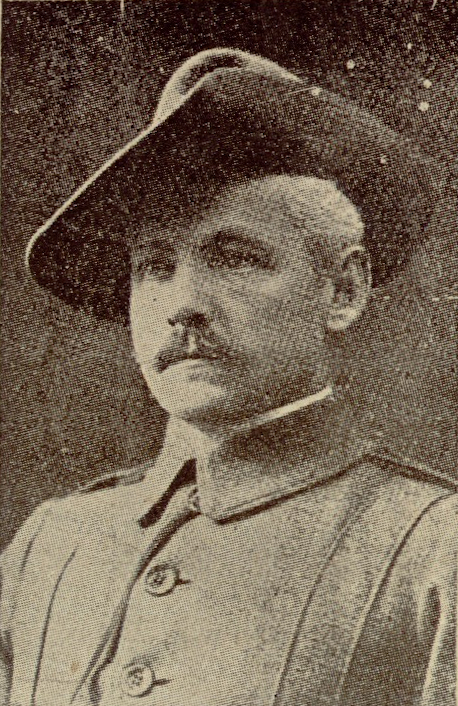

At 5:30 a.m., the "commandant" Józef Haller announced that 6,600 Sokółs and 780 scouts were ready for the exercise, and another 300 scouts were finishing preparing "defensive positions" near the village of Hrybovychi. Here, in the Zamarstyniv meadows, chaplains from the Lviv and Krakow Sokół branches, with the participation of the Sokół choir and the Sokół orchestra, celebrated a field mass.

The "game", which lasted from 6 to 9:30 a.m., even involved the cavalry of the Lviv and Krakow Sokół — 90 cavalrymen in total. The only thing that distinguished these manoeuvres from regular military training was the ban by the authorities on firing real ammunition.

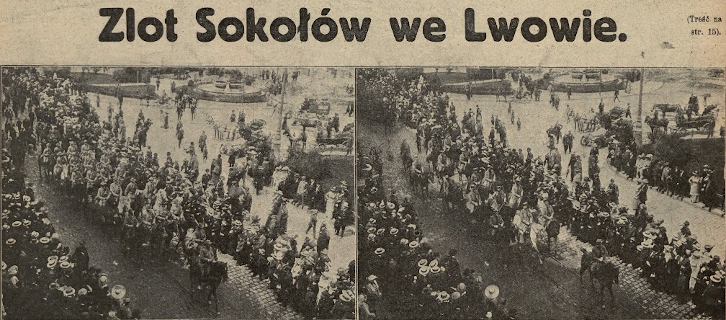

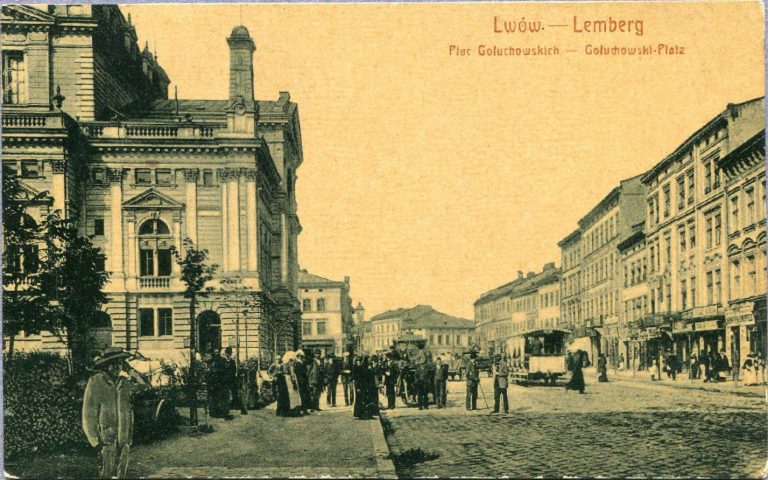

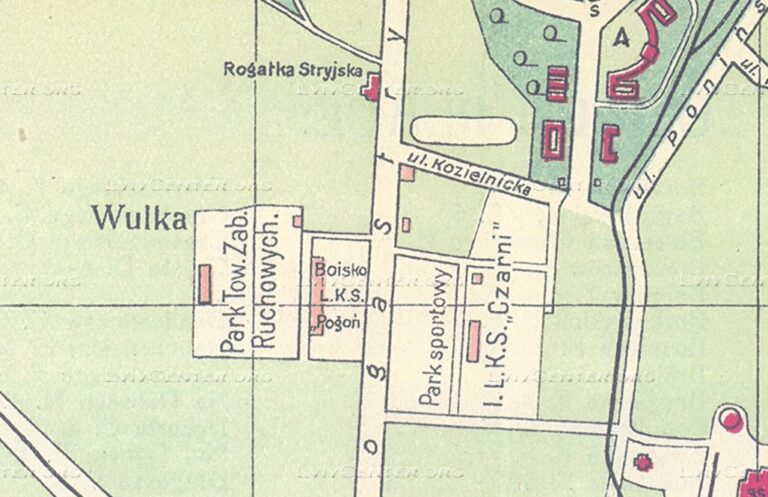

After breakfast, which was held along the Żółkiewska road, the scouts and the Sokółs went to the post-exhibition area. They walked along ul. Zamarstynowska, through pl. Gołuchowskich, ul. Karola Ludwika, ul. Akademicka, ul. St. Nicholas, ul. Zyblikiewicza to the stadium of the Physical Activities Society (pol. Towarzystwo Zabaw Ruchowych) and the Pogoń Club.

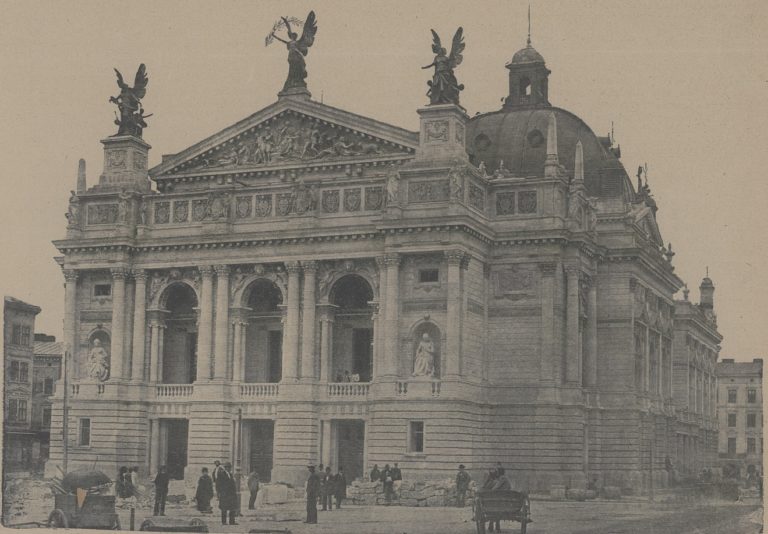

On the way, they were separately saluted by the seniors of the Lviv Sokół, who came to the City Theatre with the organization's banners, while participants of the January Uprising, accompanied by the Sokół leadership, stood on ul. Zymorowicza. In addition, the march in which members of patriotic organizations marched with rifles, military backpacks, field kitchens, sanitary units, and bands — that is, they visually looked like a national army — was welcomed by many townspeople. At 2:30 p.m., the march finally ended, and the participants settled down near the Stryjska tollgate.

The rest of the program was also far from gymnastic. In addition to a lecture on the Swedish system of physical education, there were exercises with weapons, drills, and the basics of camping. There was also a parade and an imitation battle with an attack and retreat.

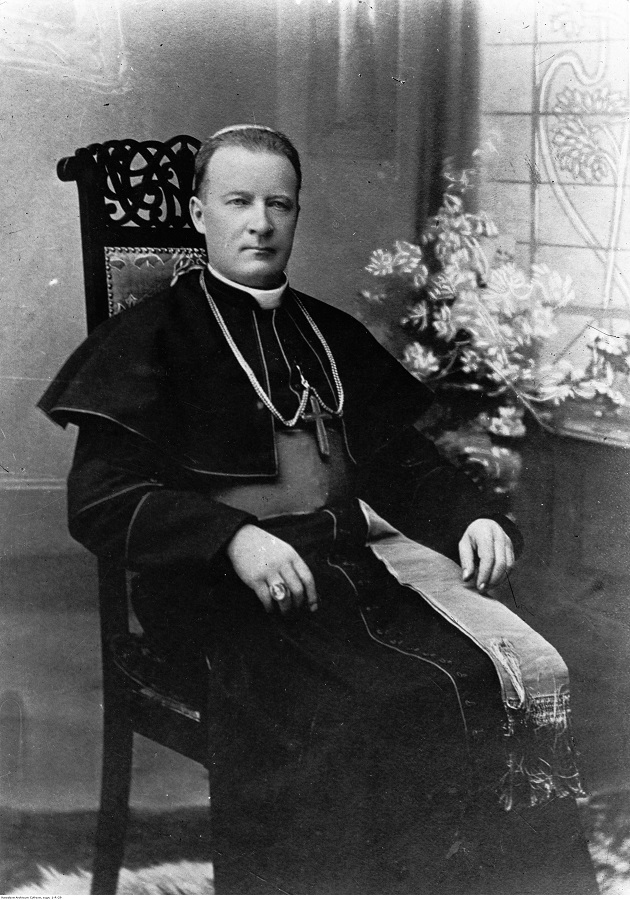

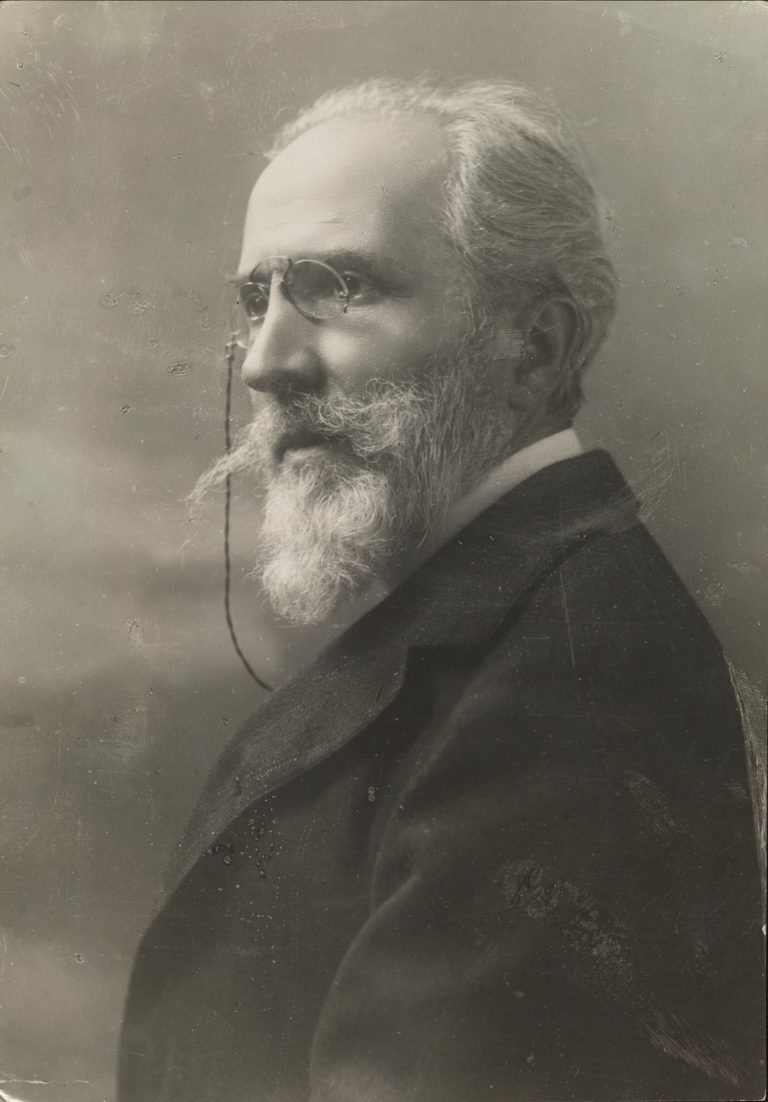

Naturally, such an attraction allured a lot of spectators as well as the national elite: Archbishop Józef Bilczewski, Bishop Władysław Bandurski, Vice-President of Lviv Tadeusz Rutowski, many officials and even military officers. The "host" of the celebration, "standing on a high platform", was the head of the Lviv Scout Movement, Kazimierz Wyrzykowski.

At 8:30 p.m., the visiting Sokółs and scouts marched to the station, and journalists later calculated that in less than a day, they had marched an average of 42 kilometers each, initially in the rain and without proper food.

Interpretation of the event in the Polish and Ukrainian press

It was a reason to be proud of "our army", especially now when (compared to previous rallies) this status was not even particularly disguised. The article on the front page of the Kurjer Lwowski, for example, was entitled "The Military Sokół".

The article discussed changes in the Polish national consciousness over the past 50 years. Supposedly, when the gymnastic society was formed, some voices said that it was a preparation for new uprisings and new losses. At that time, these voices were opposed, saying that it was only about sports training. This kind of logic went on to say that since the generation that remembered the catastrophe after the 1863 uprising was passing away, the next generation should be more optimistic. However, optimism can lead to a new catastrophe, so one should be better prepared for the fight by studying weapons and forming an army in advance, not just promoting physical education. Because the nation needs heroes, not martyrs. Hence, the parade was interpreted as a "small army campaign" and the event itself as "military training."

The government-run Gazeta Lwowska described the event very favorably, with obvious sympathy. It mentioned the support of the spectators, the 12,000 participants, and the performances at the Stryjska tollgate. The issue of militarism, however, was skilfully avoided. Reading the article in this newspaper, one could get the impression that it was an innocent scouting game, not a simulation of war.

Logically, Ukrainians were outraged, especially as the Diet (Sejm) elections were just coming to an end. Moreover, in the spring of the same year, two months before the Polish "military rally", the Austrian Ministry of the Interior did not allow the creation of the Ukrainian Rifle Society. The reason was that such a society could train its members in military affairs under the guise of sport.

In the end, the Sich Riflemen, as part of the Ukrainian Sokil, were able to demonstrate that they were not going to give up. For example, in March 1914, 120 Ukrainians demonstratively marched to the Kaiserwald for shooting lessons.

* * *

Thus, by 1913, sports associations had finally turned into paramilitary ones, as a fit body was supposed not only to work for the good of the nation but also to fight for it.

Thanks to the fact that the Polish Sokół enjoyed the unconditional support of local self-government, clergy, and influential politicians, the Poles managed to hold not just a parade, but a real military march on the eve of the Great War, as well as to show that their claims to Lviv were backed by military force.

A simple trick like declaring the Russians the official "enemy" in the maneuvers allowed them to maintain the appearance of loyalty to the Austrian authorities.