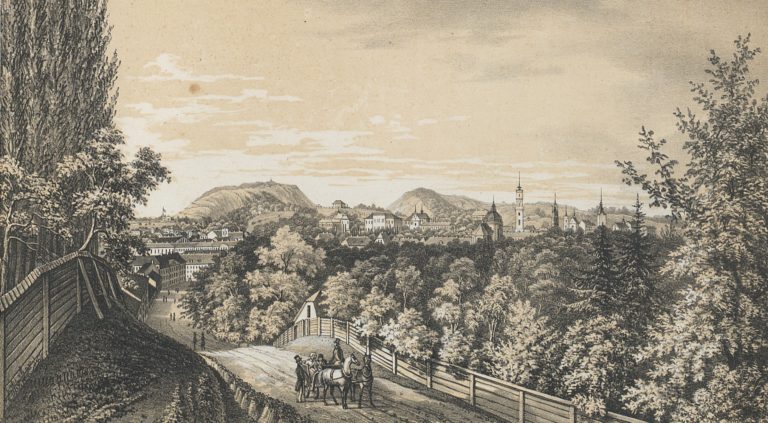

The best way to see how Lviv and Lvivites wanted to "show themselves" to the guests of the city is through the stories of imperial visits. In addition to the fact that these visits were very important and revealing, their example can be used to trace the evolution of welcoming guests and self-presentation over the course of half a century. However, this is also an extreme example as, for Lviv, there was not and could not be a more important guest in those days. And there were other visits and other guests, less significant, but no less revealing.

Due to examples like the visit of Henryk Sienkiewicz, the Shah of Persia or Georg Brandes, one can also understand what was seen under the term "our city" in those days; who presented this city, how and to whom; where bureaucratic things had more importance than national ones and where it was vice versa. Moreover, it can be seen how many national aspects permeated the bureaucratic sphere and how the visit of a guest was both a protocol event and a part of modern public politics when politics "came out" of the aristocratic salons "onto the street."

Furthermore, the difference in the positions held by the Poles, Ukrainians, and Jews can be seen better. Actually, the last two groups did not show the city but themselves in the city or could even basically prove their very existence. Instead, Polish activists could indulge in welcoming their "national prophet" Sienkiewicz with all the attributes with which they had greeted the emperor, repeating rituals, routes, and elements of mass mobilization.

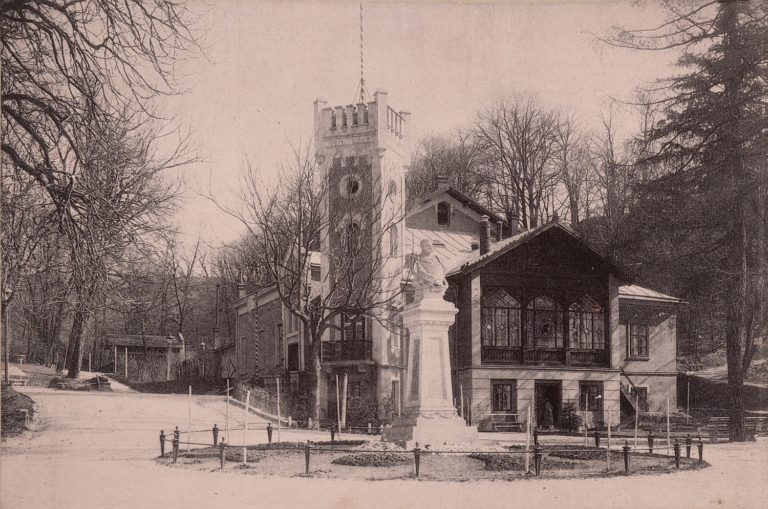

In addition, the Poles of Lviv could keep Viennese aristocrats company during a dinner party. Also, they could invite high-ranking guests to the Strzelnica (Shooting Range), which combined a club for the local economic elite, an important public institution, local self-government, and patriotism.

* * *

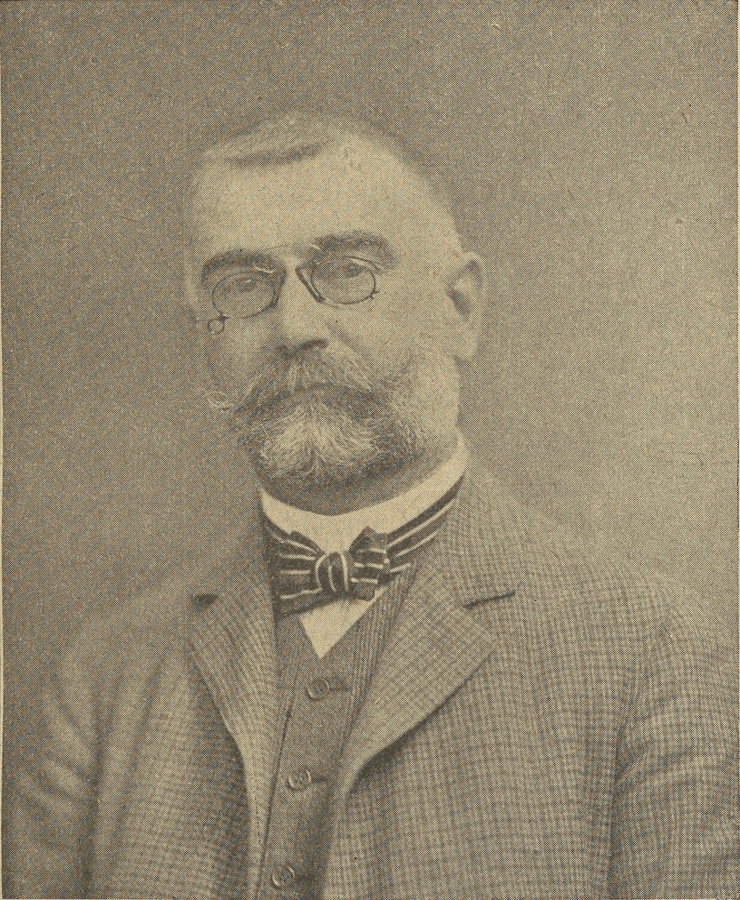

This was what happened, for example, during a meeting of government ministers in Lviv on October 5, 1909, actually, not just ministers, but Poles and persons who were not strangers to Lviv. The Minister for Galician Affairs, Władysław Dulęba, had studied in Lviv and had been a member of the City Council. The Minister of Finance, Leon Biliński, had been the rector of Lviv University.

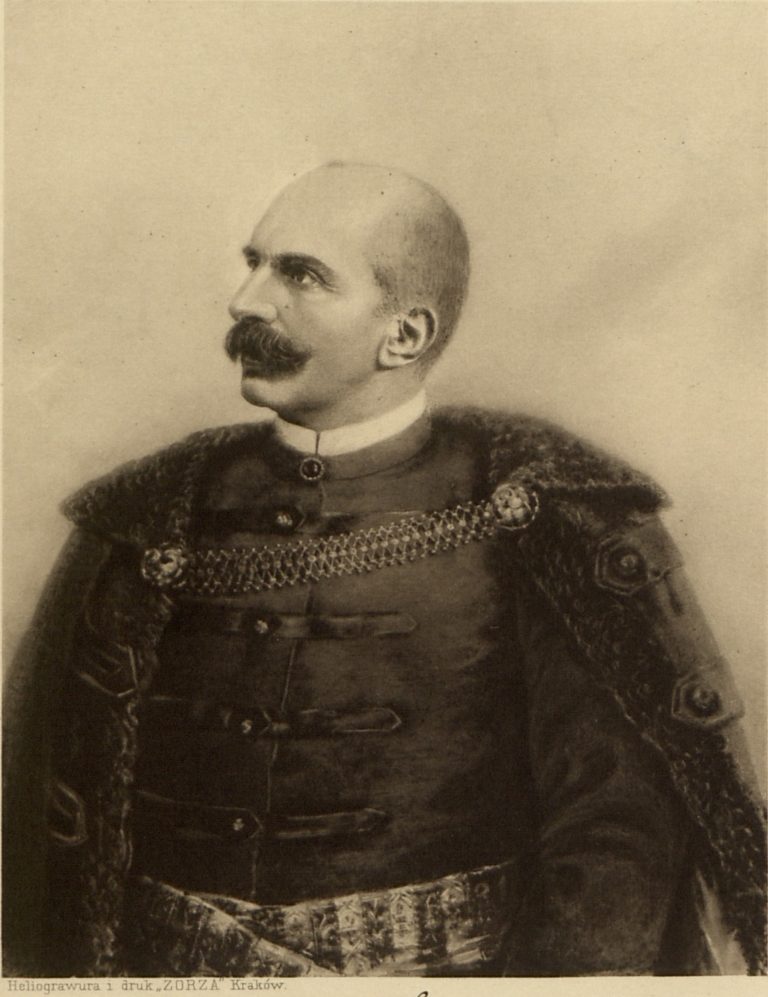

The banquet at the Strzelnica became, in fact, a festive meeting of top local politicians, it was attended by the provincial marshal, Stanisław Marcin Badeni; the head of the Polish circle in the Diet (Sejm), Stanisław Głąbiński; Franciszek Tomaszewski, a member of the Diet; virtually all members of the City Council of Lviv, as well as the city president, Stanisław Ciuchciński.

It all would have gone as loyally and calmly as possible, if there had been no leftists among the members of the City Council, who were also invited to the banquet. During his toast, Aleksander Lisiewicz, a member of the City Council, instead of praising the guests like all the previous speakers said that the support of Lviv from the government and from the Lvivites in the government was just words, not sustained by any deeds. He was, of course, "discussed" by his colleagues at the tables, but the unpleasant impression remained. Still, the Strzelnica was not a place for discussions but rather an elite club, whose "right" to determine the city's policies was occasionally undermined by various circles.

However, it does not follow from this that the Polish leftists in Lviv simply sought some kind of abstract social justice. They believed that since Lviv was destined to be the center of Polish national life, it should be used to the full, not only because of agreements at the level of "the Strzelnica — Government Ministers", especially since there was little practical benefit from such agreements. Besides, Lviv was growing and developing, so managing the city through the "elite patriotic club" was no longer effective.

When Lviv was visited by representatives of the Habsburg family, the situation was somewhat different. Here the local or provincial government had to demonstrate a policy of cooperation with all the peoples populating the province. The exception was the so-called visits incognito, when it was possible to avoid a series of political manifestations, merely enjoying the company of aristocrats.

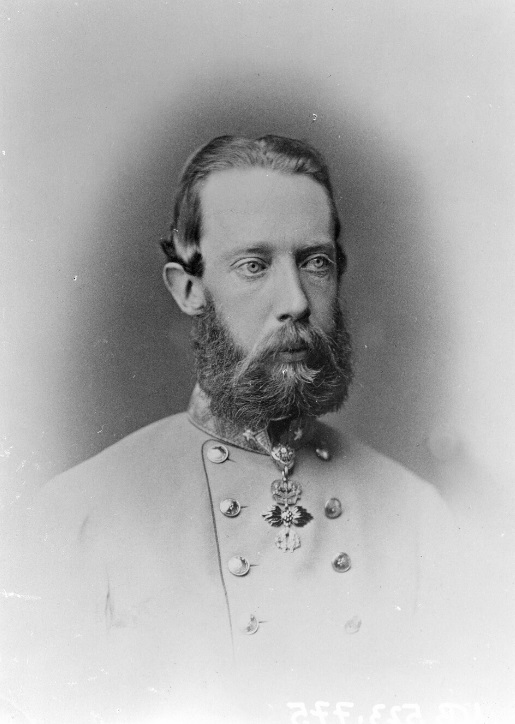

One of such visits incognito took place on September 19, 1896, when Archduke Ludwig Viktor Joseph Anton von Österreich came to Lviv. The guest was met by the governor Eustachy Stanisław Sanguszko-Lubartowicz, then there was a visit to the warehouses of the Red Cross and an audience with representatives of the Red Cross in the governor's office. Next, there was a breakfast in the governor's office in the company of aristocrats, followed by dinner at Countess Waleria Borkowska's in the evening.

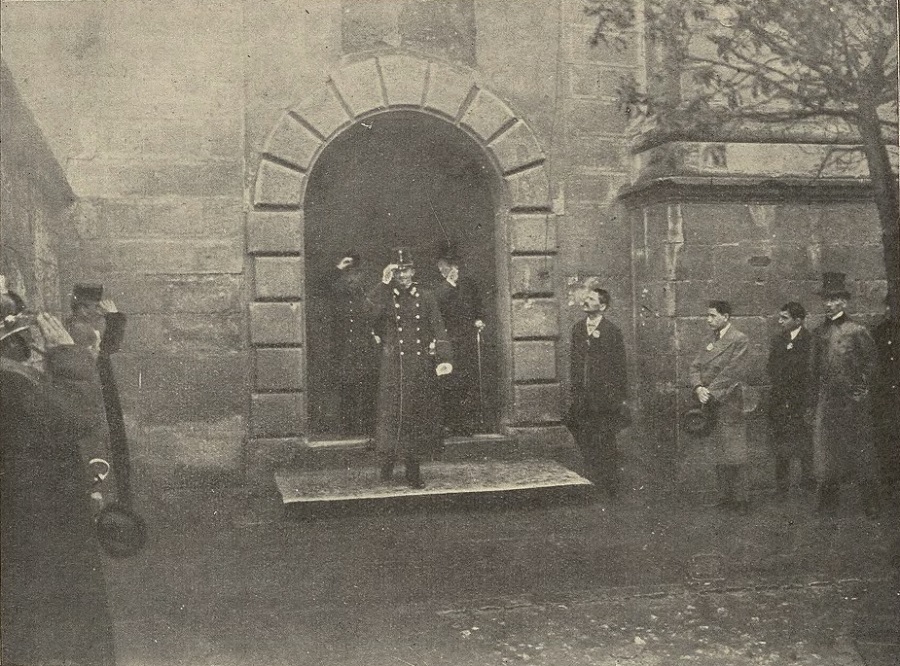

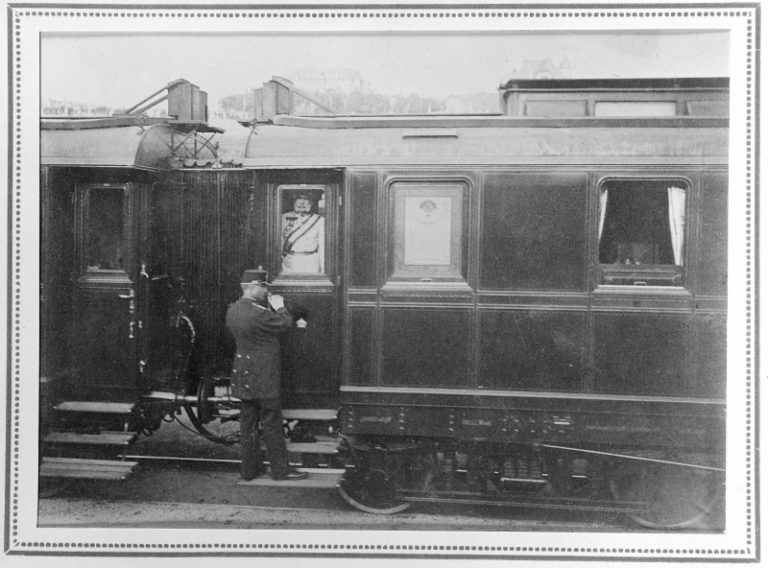

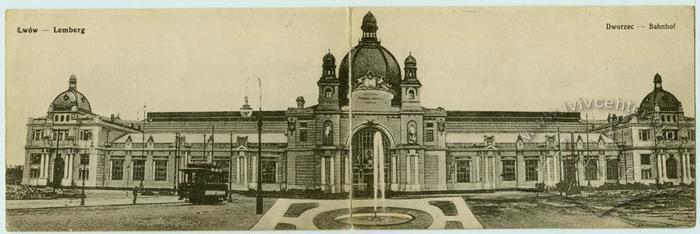

The arrival of Archduke Karl Franz Joseph, the heir to the throne, on Sunday, May 26, 1912, looked different. It was the first day of the Green Holidays (according to the Gregorian calendar); in view of that, the programme of the annual election of the "chicken king" was quickly reduced to a minimum, as everyone went to the railway station to meet the distinguished guests. Provincial Marshal Stanisław Badeni, Deputy Governor Michał Bobrzyński, President of the City of Lviv Józef Neumann, members of the City Council clad in Polish national costumes, rectors of the University and Polytechnic, Ukrainian politicians of various orientations, officers were present on the platform, as well as an honour guard of the 30th Infantry Regiment.

The national confrontation between the Ukrainians and Poles, as it became clear already on the platform, was one of the key issues. Józef Neumann, the President of the City, included a passage about Lviv as a "Polish Catholic stronghold in the East" in his welcoming speech. In response, the Archduke spoke of "the two peoples of the province." In the end, the guest was greeted alternately with shouts of "Niech żyje!" and "Славно!"

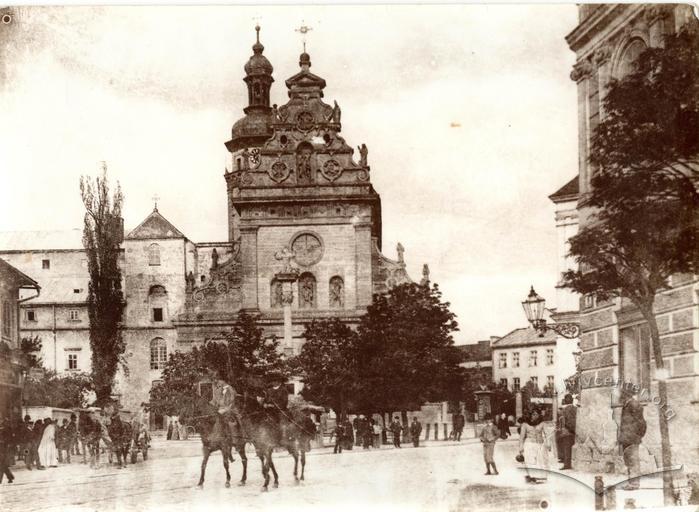

As was appropriate in such cases, the distinguished guests travelled from the railway station to the center of the city in the company of the governor. On the square they were greeted by the railway workers, the railway orchestra performing the Austrian national anthem. The procession consisted of several carriages, on the way they were awaited by members of guilds, schoolchildren, representatives of numerous associations and societies; in front of the governor's office, there were military officers. That is, everything was happening according to the scenario of imperial visits. The difference was that to express their joy, the Ukrainians were allocated a separate place: part of the route from the church of Mary Magdalene to the post office. Members of the Sokil Society, girls in national costumes and Greek Catholic seminarians gathered there.

In the afternoon, the potential heir to the throne received various guests in the governor's office. The Russian and German consuls, heads of all three main Christian churches of the province, representatives of three national groups (Ukrainians, Poles and Jews), rectors of educational institutions arrived. Moreover, the archduke even mentioned the "250th anniversary of the University", which clearly looked like flirting with the Polish politicians. In the evening, there was a dinner party in the Lubomirski palace, followed by a ball at the governor's residence later.

Monday, May 27, began with a divine service in the Bernardine church. A "review of schoolchildren" at the stadium was cancelled due to heavy rain, so they immediately moved on to a breakfast for 40 people at the provincial marshal's. After breakfast, the Archduke had fun at the Strzelnica shooting at targets and then, accompanied by the governor, went by car to see horse races. After a late lunch at the governor's residence, the archduke left for Kolomyia; he was again escorted to the railway station by the governor and the president of the city.

Therefore, the programme was more like entertainment, while Emperor Franz Joseph, known for his diligence, was mainly engaged in inspecting various objects. Nevertheless, the main attributes of the "imperial visit", such as onlookers, a guard of honour, travelling in the company of the governor, were present.

There were also traditional Polish-Ukrainian conflicts over the opportunity to represent themselves before the monarchy. Special announcements in Polish newspapers reminded that the "real civil guard" would have armbands only in white and red (that is, Polish) colours. The owners of any other armbands did not belong to the city civil guard.

Instead, the Ukrainians claimed that, after greeting the archduke and his wife with friendly shouts, they had "driven away" the Poles in national costumes (who were riding in the same procession) with shouts of "Shame!" and "Go behind the San [river]!" "Driving away" is a very dubious statement, considering the fact that the procession did travel along a specified route. However, the fact of such a "manifestation" directed towards Polish politicians cannot be ruled out.

Unlike the Poles, the Ukrainians could not afford to welcome guests as the hosts of the city. On their part, it was more like invitations to certain institutions or individual buildings. In 1909, a group of Russian scholars led by Alexander Pogodin visited Lviv. The programme included visits to the Prosvita society, the Taras Shevchenko school, the Narodna Torhovlia (Peoples' Trade) cooperative society and the "Sokil market", where the guests bought Hutsul clothes. The only "official" point of the programme was the Diet, but even there the visitors were given a tour by a Ukrainian official. Also, there was the railway station, where the guests were escorted by a group of Ukrainians, but this point could not be avoided.

However, the Ukrainians, although they were represented in Lviv as a kind of national enclave, were not the same as "peasants." Ukrainian peasants appeared in the public space of Lviv mainly for assemblies and demonstrations, while with Polish peasants, it could happen in various ways.

In 1912, some peasants were brought to Lviv from villages near Łańcut, as would be said now, "with the help of the local member of parliament", Prince Andrzej Lubomirski, who paid for this excursion. The peasants were to see how land consolidation occurred, when small plots in different places were exchanged for a single larger one, more convenient for cultivation.

At the League for Industrial Assistance (pol. Liga pomocy przemysłowej) they were met by the prince himself and other dignitaries. In two days, the peasants visited the villages of Sknylivok and Pidberiztsi to see "positive examples" of land consolidation, as well as the Ossoliński institution, Prince Lubomirski's machine factory, the League building, the Diet, the Przeworsk dairy shop, and, of course, the Panorama of Racławice in the Stryisky Park, a mandatory point of any patriotic event.

The history of the First World War shows how important welcoming visitors and presentation of the city were. During the Great War, the functions of "formal welcomers" of officials were transferred to the military administration, while local politicians were left only to meet their national leaders.

* * *

So, from the examples of the visits, it can be seen that only the Poles could afford to use the concept of "our city" to the full. They controlled the local government, the majority of the city's population was Polish, the aristocrats who could "invite" representatives of the ruling dynasty were also Polish. For the Jews and Ukrainians, when they had to welcome high-ranking guests, the only option left was "we are in the city" or even "we also are in the city."