In the period of Galician autonomy, many different associations and societies functioned in Lviv, including women's ones.

Women actively participated in nationwide actions, in various social actions and thematic events held in the city, though almost always as an "auxiliary force." This happened even during charity events or even when the charity was related to such a supposedly women’s matter as helping brides.

This activity was headed mainly by educated women, who, moreover, had enough money to not spend all their time in low-paid jobs. At the same time, women, who were active in the city’s public space, represented the entire "social palette" of their time. They took part in workers’ demonstrations in Lviv; in particular, among the five victims of the police crackdown in 1902, there was one unemployed woman. Female workers organized strikes and joined workers' strikes (for example, in 1905). Female teachers conducted the so-called additional classes in physical education for girls in the city schools, when healthy youth became the goal of national education. The wives of aristocrats patronized charity events, women were present in student societies (from the 1890s) and in youth patriotic organizations.

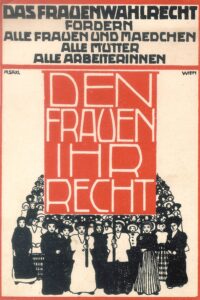

At the same time, the position of women at the legislative level was unequal, the disparity ranging from voting rights or education to wages. It was believed that women should "assist" men and that they were objectively less productive. All this led to the emergence of a women's movement as a movement for the emancipation and equality of women. First of all, women demanded equal opportunities with men in the field of education and voting rights. From that time on, women began not only to participate in "men's" national or social actions and events but also to organize their own ones, where their rights became the main agenda.

Just a few purely "women's" actions of this kind took place in Habsburg Lviv: assemblies with demands to expand women's rights, as well as the so-called Women's Day in 1912. At the same time, the last one is almost the only exclusively female action that really took place not indoors but in the space of the city.

Women's and national issues

In Lviv, women's activism was formed on a national basis, while their activities, which were chiefly publishing, charity, lectures, associations based on interests, took place in the fairway of national policy. Even those organizations that declared "non-partisanship" gravitated in one way or another towards some political force, which, in turn, was national to one degree or another.

On the other hand, the movement for women's rights, which ran parallel to this activism, although it declared itself to be “supra-party”, nevertheless cooperated more closely with the left-wing movement as both considered themselves to be supra-national.

For Lviv, however, women's actions — that is, joint activities of Polish, Jewish, and Ukrainian women — were rather exceptions. It was considered the norm to "work in national associations." In spite of the fact that the demands for electoral and educational rights were common for the whole empire, in a short time the national still prevailed over the social.

So for Polish, Ukrainian, and Jewish women, in the end, emancipation was taking place in parallel, so to say.

At the same time, the activity of women in associations did not always mean their inclusion in the emancipation movement. Most of the participants of women's charitable organizations did not associate their activities with emancipation and did not want to be labeled "emancipants." Regardless of this, though, they still pursued emancipation or enjoyed its gains, such as access to education.

Women's Days in 1890-1910

Lviv women actively joined the all-Austrian women's movement almost immediately. This movement coincided in time with a wider trend of holding assemblies and signing petitions.

In the spring of 1890, women's organizations of Lviv collected signatures for a petition to the State Council with a proposal to grant women access to higher education. In December 1890, a meeting was held in the Lviv City Hall where the demands of voting rights equal with men were discussed. It was attended by women but not considered purely "women's."

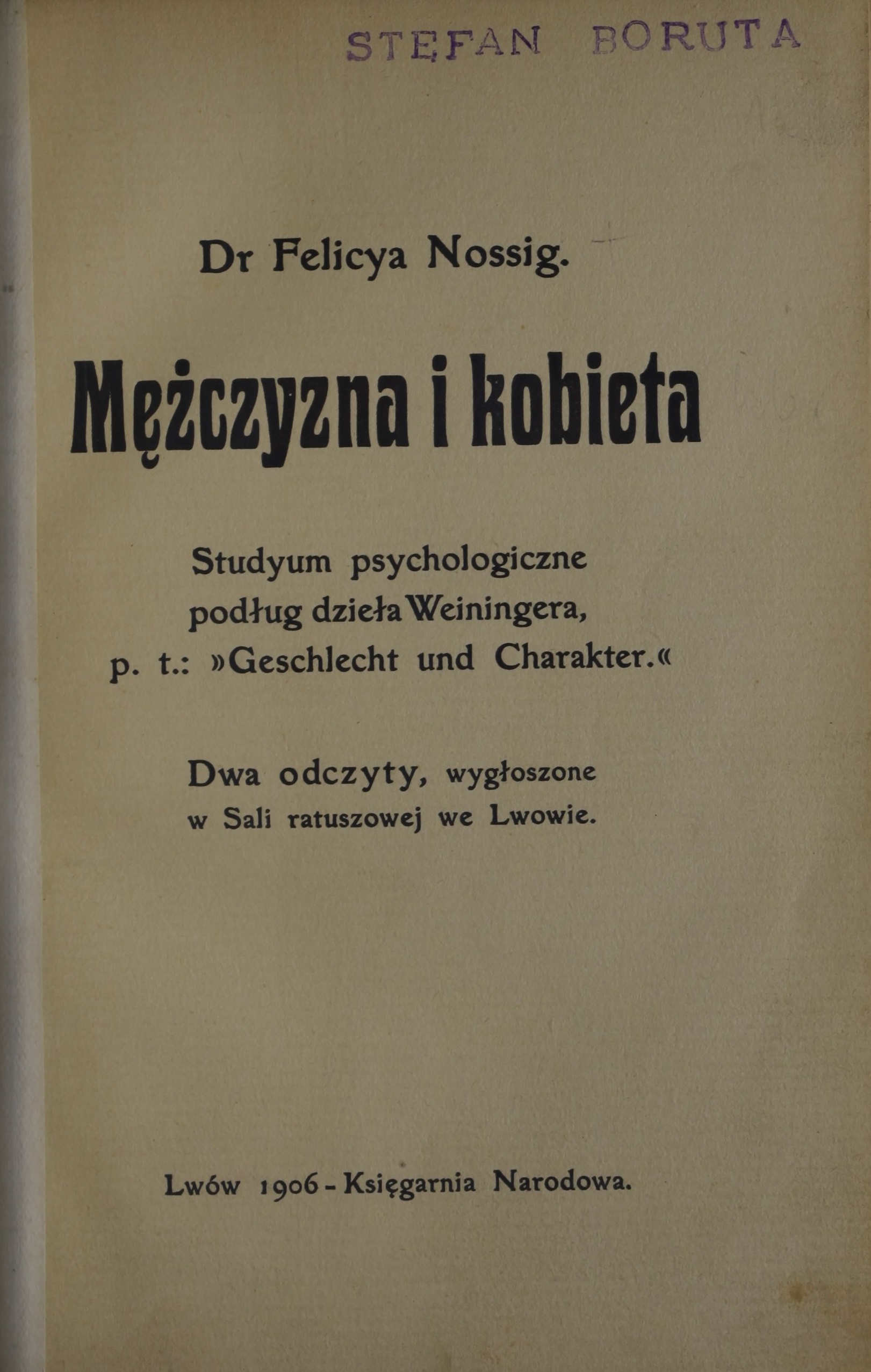

On April 10, 1892, the "First General Women's Assembly" was held in the City Hall. The main demand of this meeting was the introduction of universal suffrage for women and their equal participation in political organizations. The event was attended by about 200 women and 200 men, together with representatives of Polish, Ruthenian and Jewish organizations, including Felicia Nossig, Olha Franko, and Natalia Kobrynska. Ivan Franko was present as a correspondent of the newspaper Kurjer Lwowski. Reports were presented, participants voted for decisions and supported appeals and petitions to the authorities; there were many conversations about unity and solidarity.

After this occasion, women's events took place relatively regularly and began to play a prominent role in pre-election processes. They were organized by the Women's Equality Committee. Simultaneously, smaller gatherings and actions took place. In 1907, all men over the age of 24 (then the age of majority) received the right to vote in the elections to the imperial parliament. At the same time, discussions of electoral reform for the Galician Diet (Sejm) began. All this once again brought to the fore the issue of the rights of women, who still had no suffrage in the elections both to the parliament and to the provincial Diet or the City Council.

On October 4, 1908, at the initiative of the writer Maria Konopnicka, a women's assembly gathered in the City Hall to speak out for direct, equal and secret suffrage for women in the elections to the Diet.

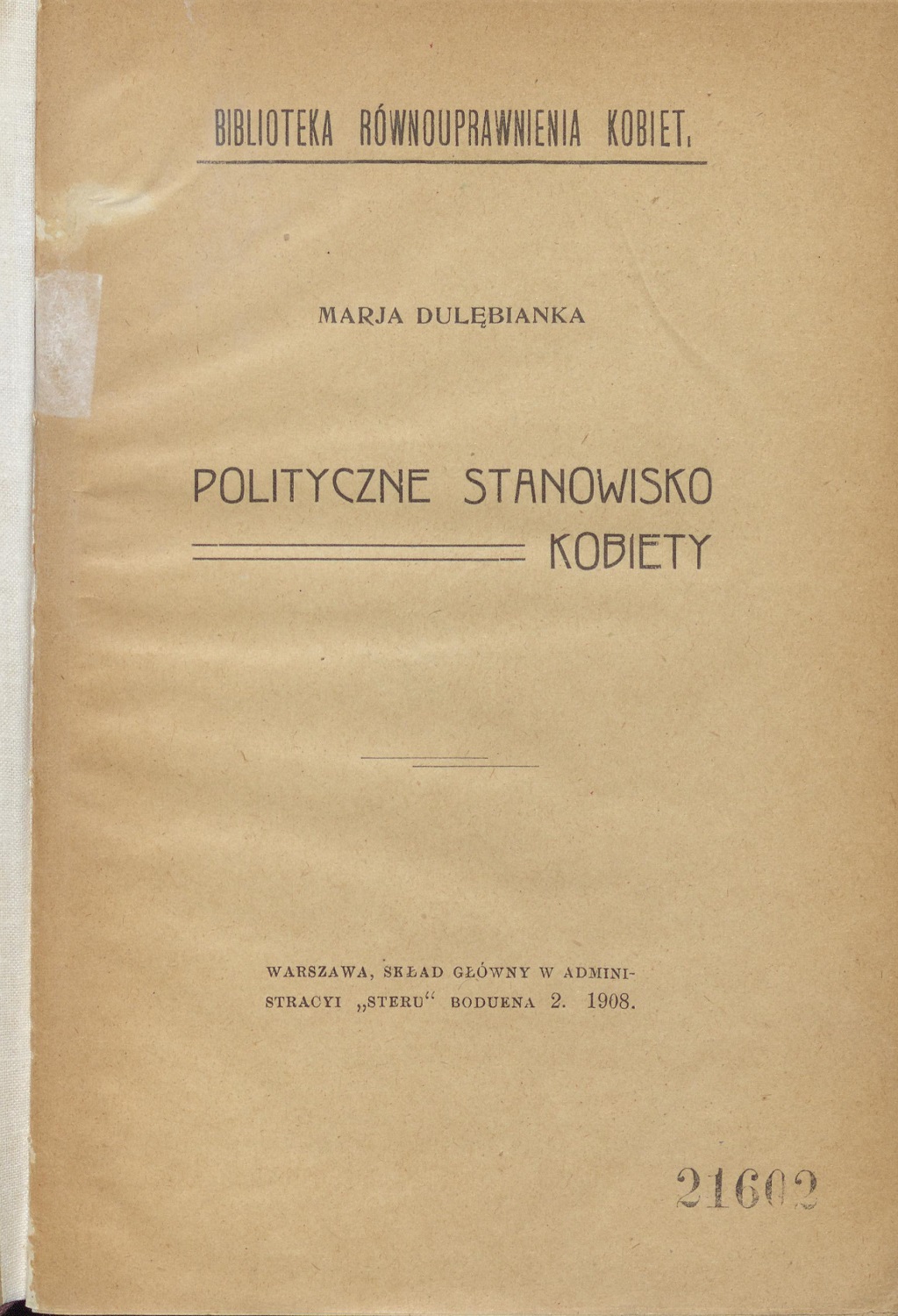

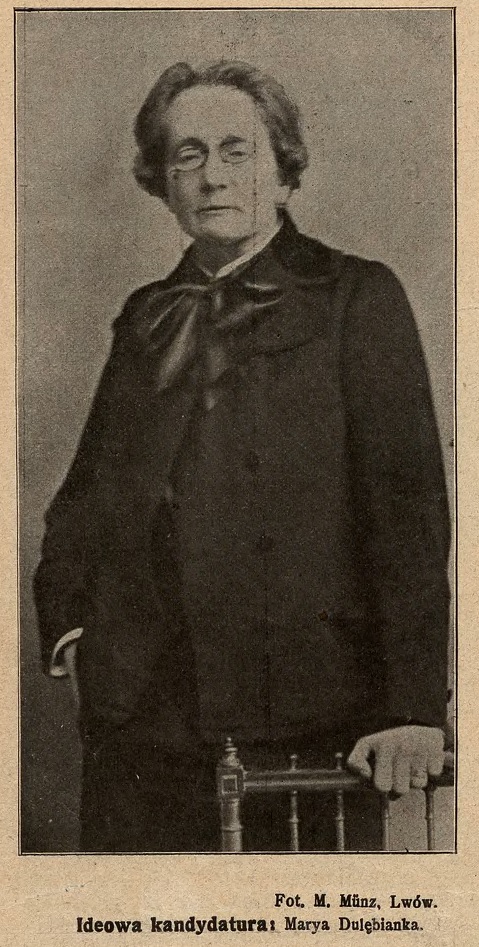

On May 20, 1909, a women's assembly was held on the matter of changes to the charter of the city of Lviv and elections to the City Council, where the activist and artist Maria Dulębianka reported. In March 1908, she already nominated her candidacy for the elections to the Galician Diet, which was rather a "performative act", because it was known in advance that she would be rejected for formal reasons, and the votes of those who voted for her would be annulled. Since these were not nearly the first steps of the women's movement, and all general slogans and mottoes about unity or natural rights had long been said and heard, it is interesting to look at how women substantiated their right in a specific situation.

In particular, they talked about the fact that women bore all the burdens of national construction, were actively involved in public life, even took part in Polish uprisings and therefore deserved equal rights with men. Since one of the main topics of that year was the Chełm Land, Polish women also spoke out against its separation from the Kingdom of Poland; so the assembly participants adopted a special appeal to the Polish deputies of the Austrian State Council and the Russian Duma. In the end, the press published an open letter to the commission engaged in updating the Charter of the city of Lviv (this commission might or might not include a stipulation on equality for women in the Charter). In this letter, women, demanding equal voting rights with men, appealed to the standards of the international Women's Rights League, which monitored the situation, as well as to Polish patriotism, because "Polish women deserved it."

As a result of the reforms, in the process of electoral rights democratization, Lviv and Krakow recognized in their charters the rights of those women who paid real estate or business taxes. In Lviv, rights were also granted to female teachers and women in public service or with scientific degrees. In general, the situation in Lviv was more "progressive", because, in contrast to Kraków (where conservatives retained strong positions), many politicians, especially socialists, began to compete for the support of women.

Another women's assembly held in the autumn of 1909 (in the City Hall again) became a notable event during the discussion of the Diet reform. Before that, women's organizations collected the signatures of "peasant women" on a petition for the expansion of electoral rights. City Council members and the president of the city, Stanisław Ciuchciński, as well as deputies of the Diet and the State Council attended the event, the main speaker was Maria Dulębianka. The male politicians present, such as Józef Hudec, a member of parliament, maintained that the emancipation process was being hindered by conservatives, so the left wing politicians should be supported in the elections.

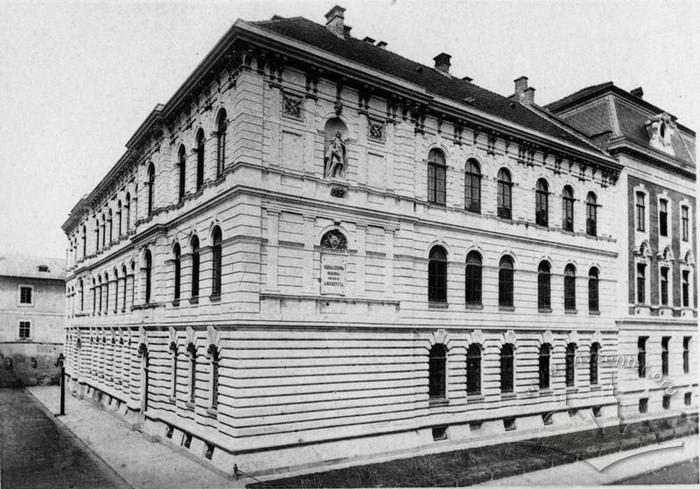

In the end, the situation developed in such a way that the socialists declared their support for women's rights to education, participation in politics, and equal pay with men. They attended women's meetings urging women to convince their husbands to vote for the left wing. It was the case, for example, at the meeting organized by the Committee for the Equality of Women in the hall of the Mickiewicz School (on ul. Teatralna) on June 3, 1911.

All this led the women's movement in Lviv to the point when in 1910 "women's" politics "went out to the streets" for the first time. This happened due to the cooperation of women's organizations that acted in line with national policy. On October 12, 1910, Ukrainian, Polish, and Jewish women first held their own assemblies and then organized a march to the Diet building. There they announced their demands, namely, giving women the right to vote in the upcoming Diet elections. Delegates from the three assemblies even got to meet with Marshal Stanisław Badeni. Maria Biletska, Jadwiga Tomicka, and Karolina Reizes (also from the social democrats) voiced their demands.

After that, the women went on a joint march along ul. Trzeciego Maja (now vul. Sichovykh striltsiv) to the Mickiewicz monument, singing the "Red Flag" in Ruthenian and Polish along the way. Having listened to the speeches of Semen Vityk, a socialist and a member of the Diet, and Karolina Reizes, the meeting dispersed. It was probably not only the first public speech given by a woman in Lviv at an open-air rally where women's rights and freedoms were discussed but also the first women's march through the streets of the city.

The Dilo reported that the police had tried to stop the march, but "the demonstrators bypassed the police and reached their goal." Polish women were criticized by representatives of the right-wing forces (the Słowo Polskie), saying that it was not good to hang out with Ruthenian women and lefties. Jadwiga Tomicka wrote in the Kurjer Lwowski in response: "We will not allow our union to be disrupted, to divide ourselves into groups."

Women's Day, May 12, 1912

Sunday, May 12, 1912, was declared "Women's Day" in many European cities, women's organizations of Austria-Hungary together with left-wing political parties joining the action. In addition to Lviv, where the "socialist women's organization" (that is, women from the Social Democratic Party) acted as the organizer, events in Galicia were held in several other cities, in particular in Krakow.

The novelty was that on this day mottoes and slogans, which had previously been heard mainly at meetings of organizations advocating for the equality of women, were pronounced during marches on the streets of the city. Most of the participants in the demonstrations were still men.

At 15:00, the hall of the Gwiazda society on ul. Franciszkańska was filled to the brim. Several hundred participants could not fit in the room, so the rally had to be held in the open air. Members of various societies, students, and activists, including Salomea Perlmutter, spoke about women's rights. An unnamed employee of the tobacco factory in Vynnyky also spoke, complaining about discrimination in wages on behalf of her colleagues, as well as socialist politicians Józef Hudec and Mykola Hankevych. In the end, the participants adopted a resolution demanding equal political rights and went on a march to the city center.

Under a red flag and banners, several hundred men and women marched through ul. Łyczakowska, ul. Czarneckiego and ul. Akademicka to the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. Here, in front of several thousand spectators, according to the then press, the activist Reizes spoke in particular. After the rally, the participants left peacefully, there were no comments from the police.

The government-run press reacted to the action as discreetly as possible, simply indicating the route and place of the meeting, as well as some speakers. Instead, the Ukrainian newspaper Dilo, reporting on the event in Lviv, was most happy about the fact that, in Vienna, where 7,000 people took part in the action on May 12, 1912, the organizers forbade the speech to be made in Polish at the rally. The Russophile periodical Halychanin wrote the most succinctly about the campaign: the reporters did not even name the speakers, describing them all as "social democrats."

* * *

Meetings and assemblies where women's rights were discussed continued until the beginning of the Great War, as did attempts to reform the Diet. In the meantime, the war exacerbated completely different problems. Women's movements, formed as national projects from the beginning, enthusiastically joined the processes of "national revival." Women's organizations were involved in helping the wounded, orphans, charity auctions and supporting national formations in the Austrian army. In addition, the period of the Great War meant a shortage of men who were sent to the frontline, so women had to "master" previously inaccessible professions. The same, by the way, can be also said about children, who were also actively involved in low-skilled work.