In the 19th century, Europe was actively engaged in "restoring traditions", "remembering history" and other things that were supposed to consolidate societies into modern nations. Accordingly, commemorative events and mass politics became a common element of public life. Citizens were intensively involved in meetings of rulers (such as the visits of Emperor Francis Joseph to Lviv), parades, and the unveiling of monuments.

The rituals used by the authorities were quickly adopted by local politicians who were busy building their national projects. Among other things, societies for "education," "hardening," and "training of the new generation" emerged, working mainly with young people and "showing" themselves to society through sports exercises and parades.

Therefore, by the beginning of the 20th century, various paramilitary structures became very common. So did their participation in mass events. Even the volunteer firefighters in Lviv were interpreted as a force that would come to Poland's defense "when Poland needed it."

The Sokół/Sokil (Falcon) gymnastic movement was an important part of this process. In Lviv, neither Ukrainians, nor Poles, nor Jews were original here. In Austria-Hungary, it all started with the Czechs in the 1960s with their slogan, "Let's get stronger." At the same time, Slovenes, Poles, Croats, and other Slavs of the empire took up the initiative. The main audience and initiators of the movement were students who organized sports societies, which eventually turned into paramilitary ones.

The Poles in Galicia were known to be "building a society," and in the conditions of autonomy, they did not openly talk about the struggle for independence. This society, however, "had to be prepared for different versions of the future." Since the army constitutes an integral part of "society," it was necessary to develop, simultaneously with the official Austrian military, "one's own" military, which would prove useful one day.

As two national projects were openly competing for Galicia, two national paramilitary movements emerged in Lviv. They were supposed to show strength, pride, victory, the nation's ability to solve something in the future, and so on, this leading directly to flexing their muscles in front of their competitors.

Furthermore, although Jewish politicians, unlike Polish or Ukrainian ones, did not claim exclusive rights to this territory, some Jewish organizations also began to gravitate towards militarization.

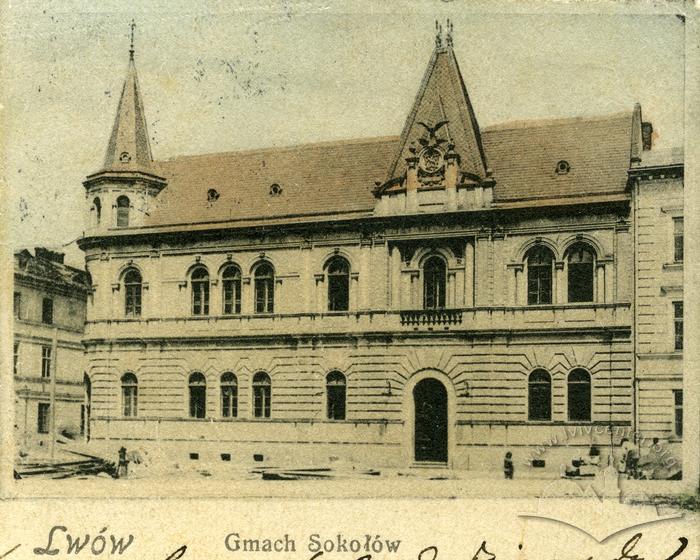

The Polish Sokół gymnastic society was founded in 1867, almost simultaneously with the introduction of the Galician autonomy, and from the very beginning of its activities enjoyed the support of local authorities. All the necessary infrastructure quickly appeared: stadiums for training, meeting halls, periodicals to promote their ideas, branches in towns, courses for teachers, etc.

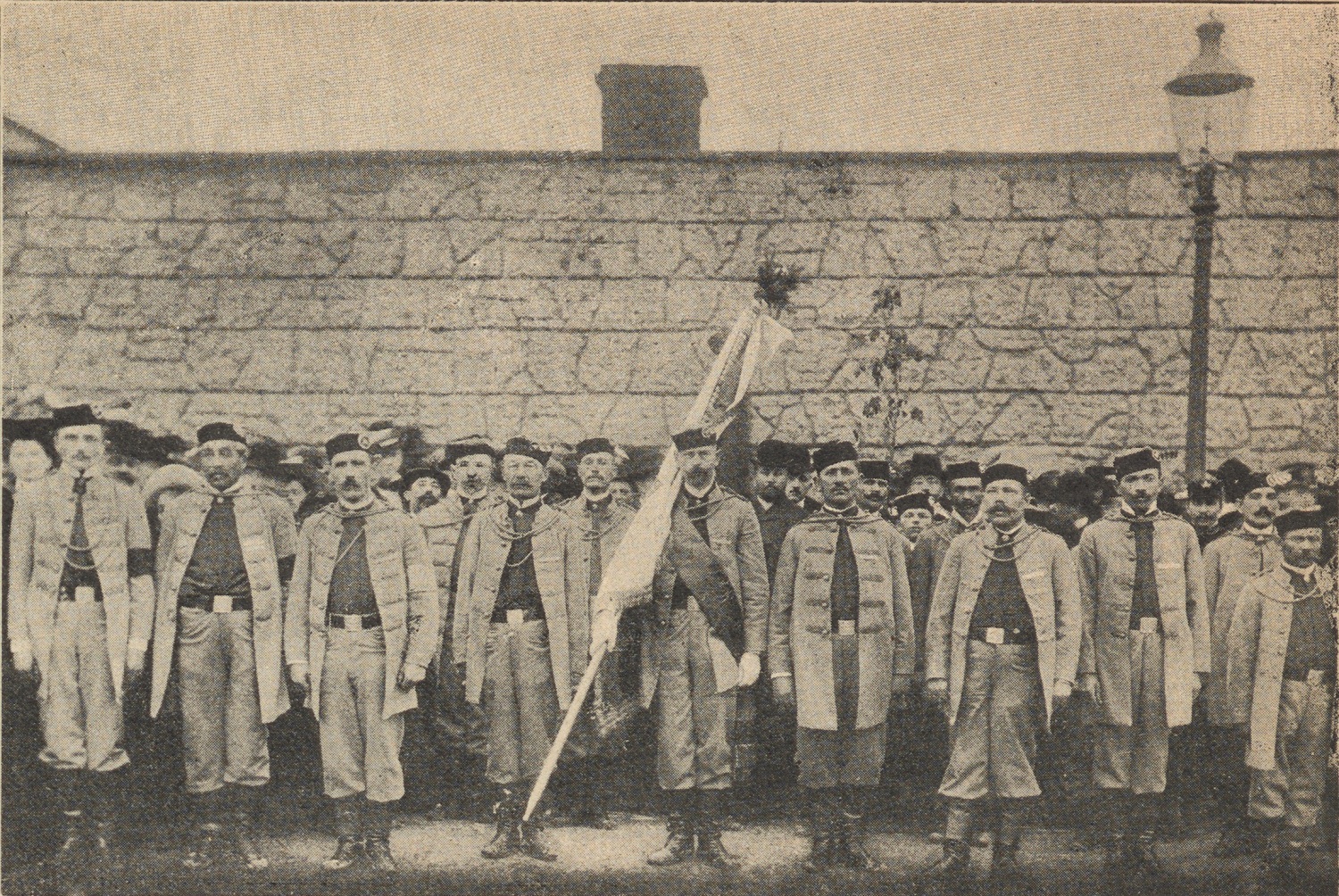

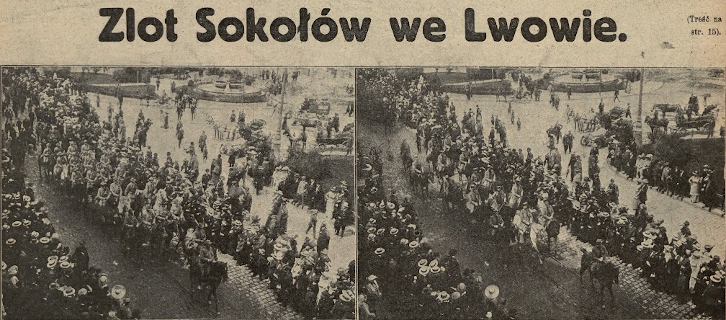

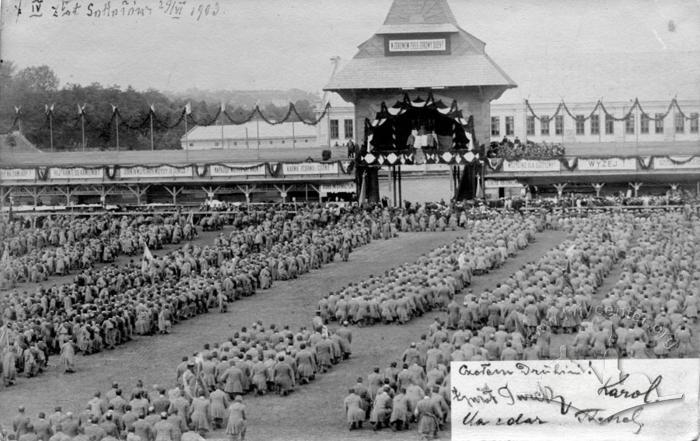

Sokół rallies (meetings with demonstrations of successes) were a separate type of demonstration that took place every few years. At the same time, the Sokółs actively participated in almost every Polish mass event in Lviv, playing the role of Polish own national "quasi army." In the early 20th century, the military component became no less important than the sports component: military instructors, uniforms, and weapons appeared. In 1913, during another gathering in Lviv, a "war game" for several thousand participants was held, not a gymnastic show.

The Ukrainian Sokil was founded in 1894. In 1900, the first Sich society was registered — also a sports and military one, but with an even greater linkage to "Cossack traditions." The Cossack history and the cult of Taras Shevchenko were what united these organizations in their opposition to the Poles. They differed in that the Sokil was close to the populist movement, while the Sich was closer to the radicals and therefore more critical of the government and clergy.

Although the Ukrainians could not count on the support of local authorities and had much more modest material support, they, like the Poles, also held their rallies, initially (since 1907) not in Lviv, but in Stryi, Ternopil, Berezhany, Kalush, and other towns of the province. Later, in 1911 and 1914, Lviv hosted two "provincial gatherings," which once again showed that the massive Ukrainian demonstrations in Lviv were mainly organized by delegates from the province.

From fun to "hardening the masses": physical education in the city

In the early 20th century, the idea that one should train to be healthy and physically strong went hand in hand with an understanding of the purpose of these efforts. The goal, as a rule, was a better future for the people, which was yet to be won in the struggle against the "others." This opinion did not dominate the public consciousness immediately as sometimes sport was also interpreted as a useful pastime and a fun attraction.

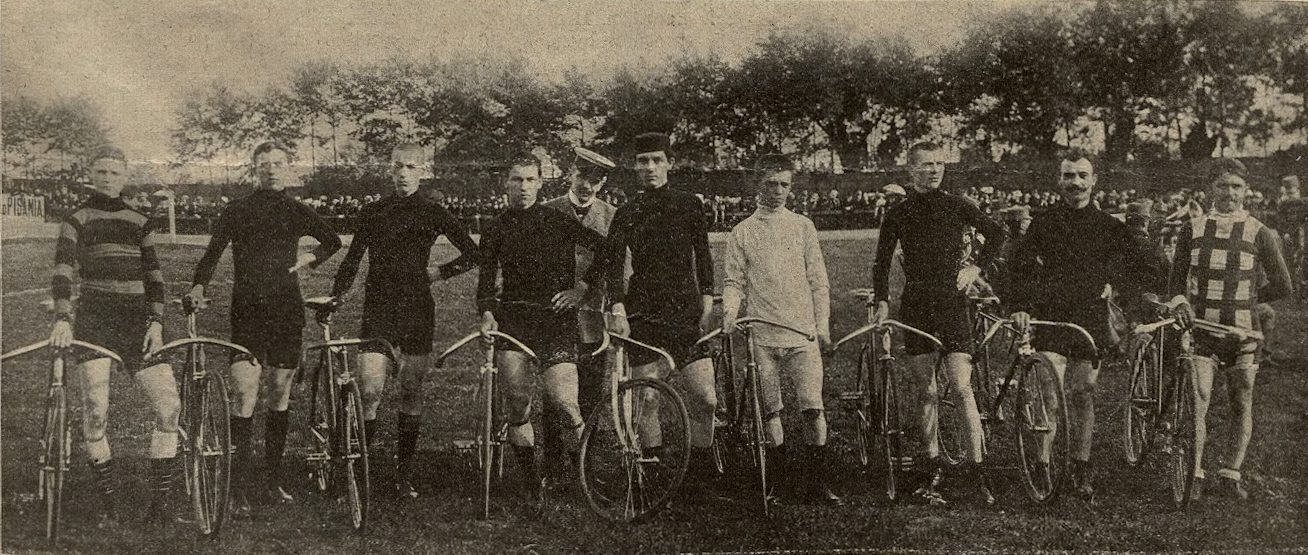

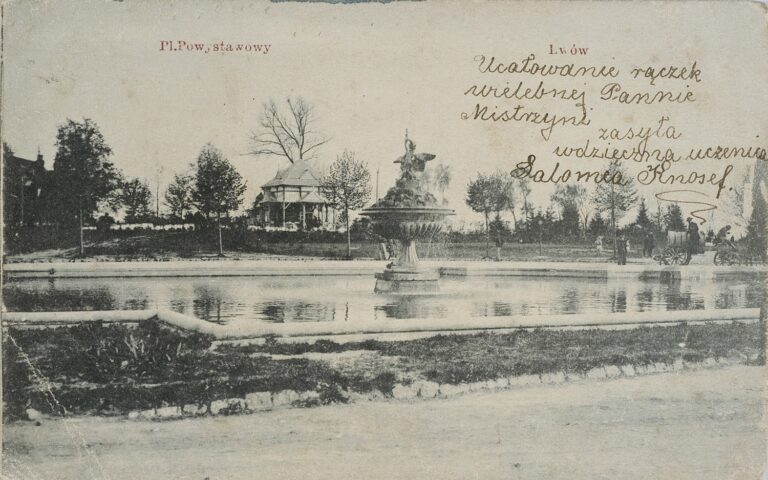

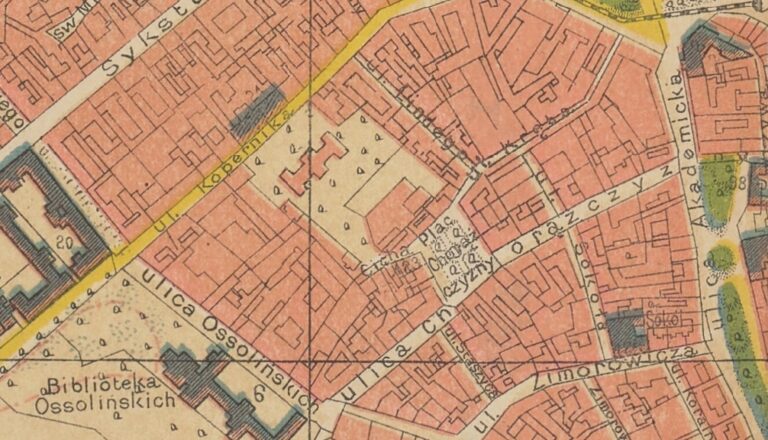

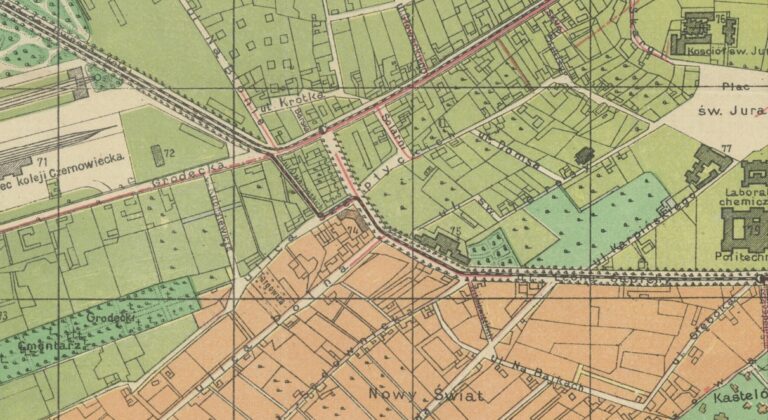

For example, in 1896, the first cycling competitions were held in Lviv. In addition to the actual race on the Lviv Cycling Club (pol. Lwowski Klub Cyklistów) track near the post-exhibition area, on 6 September 1896, the organizers held a bike ride along ul. Kurkowa (starting from the Strzelnica), ul. Czarnieckiego, pl. Bernardyński, pl. Galicki, pl. Mariacki, ul. Karola Ludwika, ul. Jagiełłońska, ul. Trzeciego Maja, ul. Słowackiego, ul. Ossolińskich, ul. Chorąszczyzny, ul. Akademicka, ending at the City Casino.

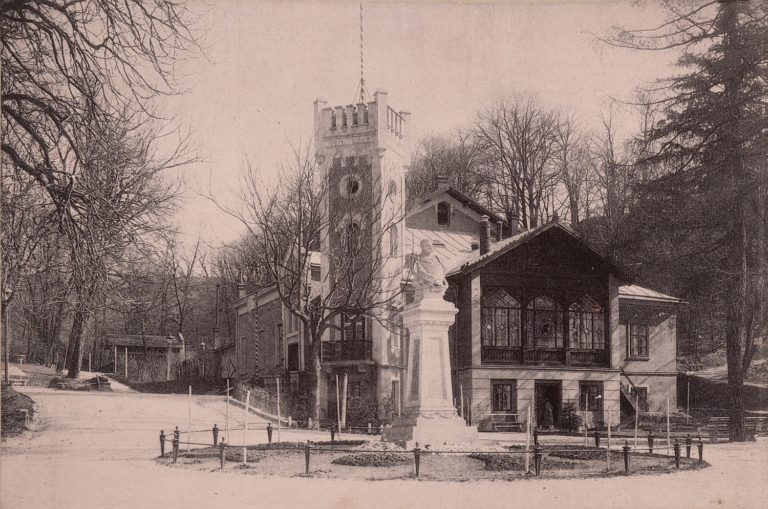

Luge competitions in March 1909, organized by the Pogoń club on its luge track near the Vysoky Zamok Hill ("on the Kisielki") and the Physical Activities Society (pol. Towarzystwo Zabaw Ruchowych) in the Zalizna Voda Park, were also perceived as entertainment. Nevertheless, in this case, too, the organizers were societies, which, by definition, worked "for the benefit of society".

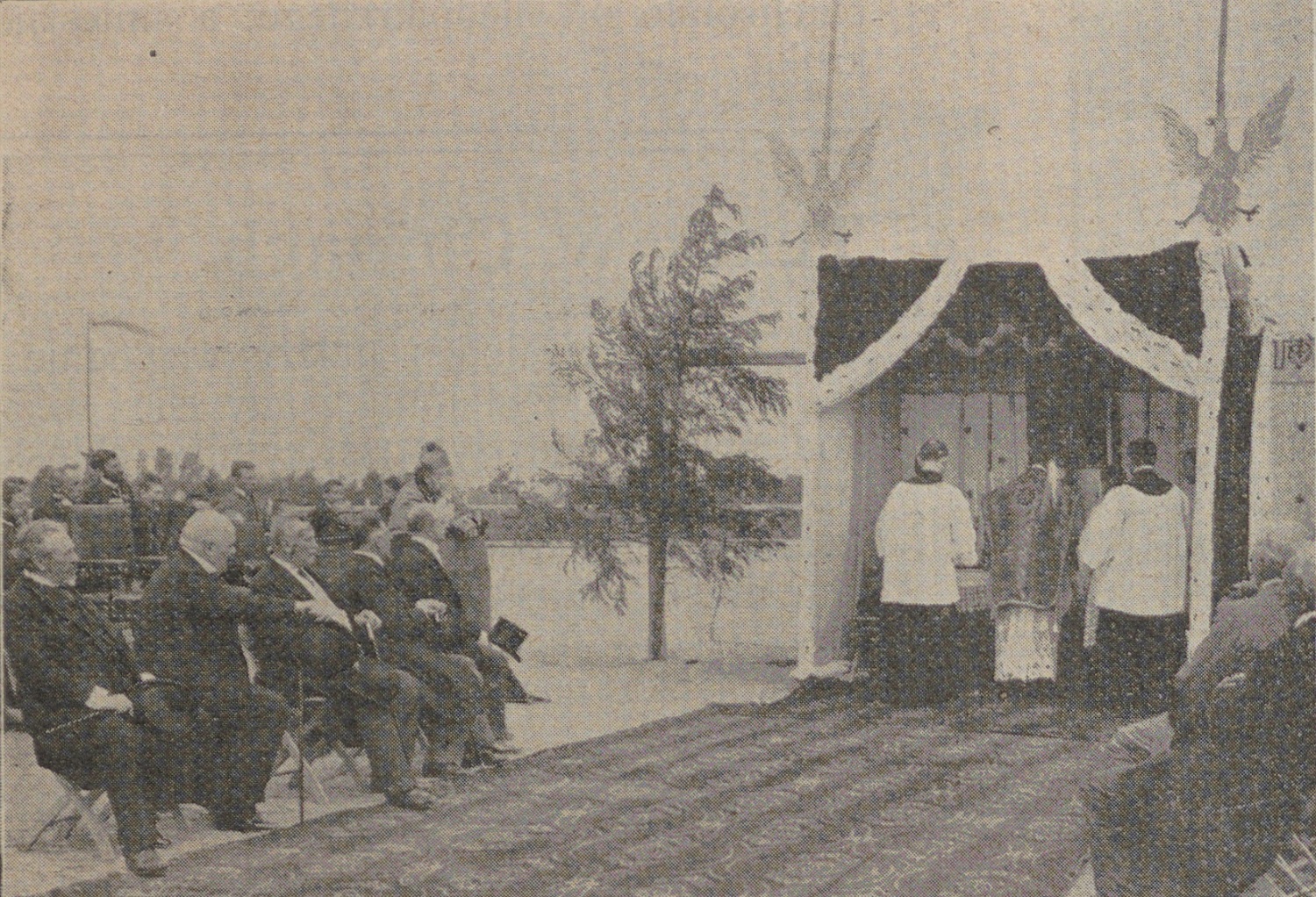

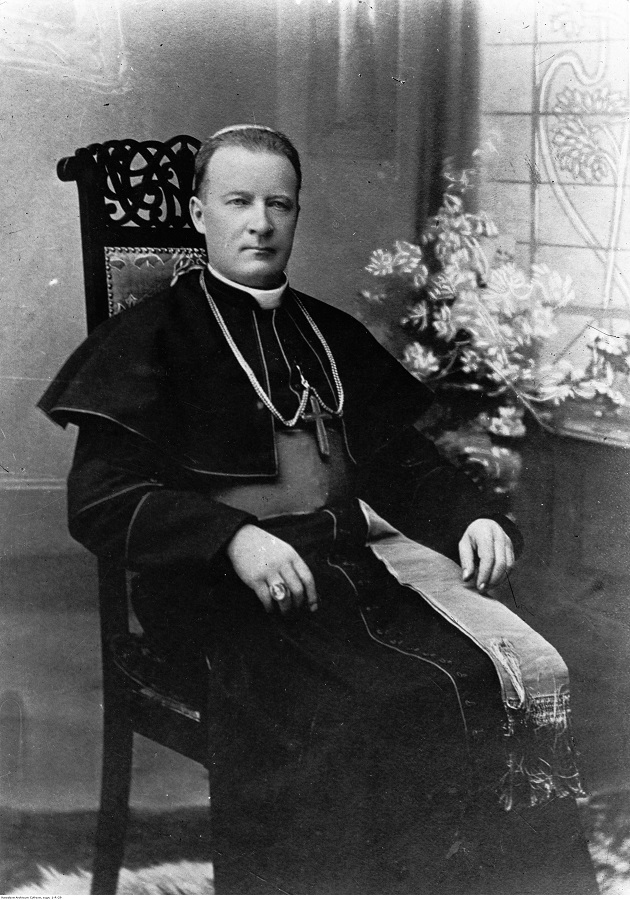

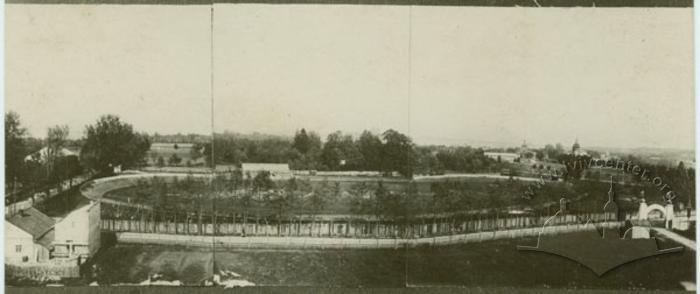

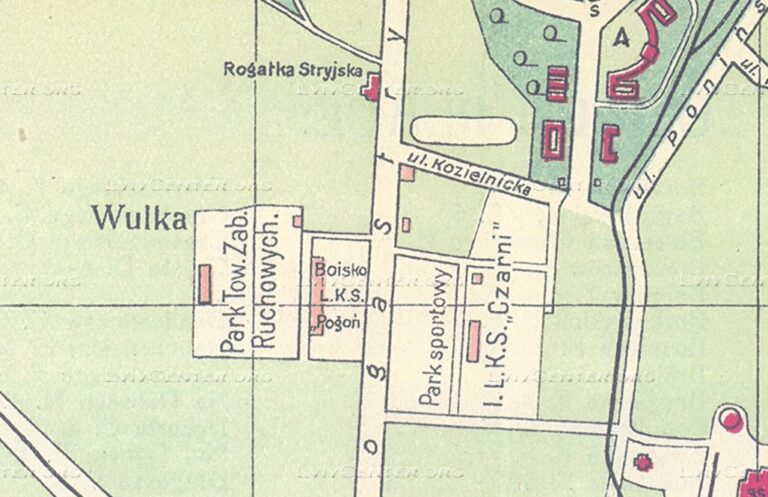

At that time, mass sports were interpreted quite differently. Since the purpose of physical education was to "harden the masses", opportunities for mass physical education were a priority. This is illustrated, for example, by the opening of the Physical Activities Society's summer sports complex, which took place on 29 June 1909 near the Stryiska checkpoint. The complex was described as the first park in the city where children, young people, and the elderly could "improve their health, increase their strength, and fortify their will." Archbishop Józef Bilczewski celebrated the field mass and consecration; among those present were Marshal Count Stanisław Badeni, Governor Michał Bobrzyński, President of the city Stanisław Ciuchciński with Vice-Presidents Tadeusz Rutowski and Karol Epler, many city councilors, the Rector of the University Antoni Mars, and the Rector of the Polytechnic Bronisław Pawlewski. Members of the Sokół, Gwiazda, Skała, Wspólność, the Sokół Volunteer Fire Brigade, and other patriotic organizations arrived in an organized manner.

There were many speeches that, in one way or another, promoted the "education of Polish youth for the future of the Motherland." Józef Bilczewski believed that it would be better for Poland if young people made noise at the stadium rather than in taverns. The president of the Fitness Play Society asked to extend the tramway to the stadium, and this would also help Poland. The President of Lviv, Stanisław Ciuchciński (who could theoretically respond to the request for a tram), stressed that the Poles are a nation which everyone around them is trying to assimilate, so they must become physically tough to fight.

The program then included a performance by the Echo Society choir, various school team competitions, field hockey, and basketball between women's teams, as well as a football fixture in which Czarni (Lviv) played against Wisła (Krakow). At the same time, "Polish records in running for 500 and 3000 metres" were set: so Lviv, in addition to being "the capital of the freest part of Poland," also declared its ambition to become the centre of "Polish sport."

In the summer of the same year, the stadium hosted a training course for teachers (17 women and 26 men enrolled in the course) who were to teach physical education in Lviv schools. The program included first aid, the importance of games for education, hygiene, organizing competitions in schools, and practical training.

As a result, mass sports and physical education became a matter of national importance, and only horse racing with sweepstakes and various stunt shows remained without a patriotic component.

Military training

Military training was the second component of the gymnastic movement after sports. Although the Austrian authorities allowed their subjects to express their national sentiments even in the army, in Galicia, this created even more problems due to the Polish-Ukrainian confrontation.

For example 1909, the 100th anniversary of the Austrian victory over Napoleon's troops at Aspern was celebrated. Galician units also distinguished themselves in this battle, so it was decided to hold celebrations in Galicia on a grand scale. In Lviv, the infantrymen of the 15th Regiment (several hundred) marched in the evening with colorful lanterns, accompanied by an orchestra, from the barracks on ul. Jabłonowskich to the commandant's office on pl. Bernardyński, to pl. Mariacki, and to the governor's office. As the newspaper Dilo reported, the garrisons in the province were allowed to "show their national features." This is where the conflict arose: although the officers' speeches were delivered in Ukrainian, services for Greek Catholics were held in the Latin rite. Similarly, the hall for the theatrical performance of "The Courtship at Honcharivka" for the infantrymen of the 15th Regiment in Lviv was decorated only with white and red flags. Such things naturally contributed to the realization of the need to have "one's own army."

The Sokół/Sokil in the city space

No more or less mass action in Lviv could be done without the participation of paramilitary structures, especially when there was a need for a so-called civil guard. However, the Sokółs also became visible in the public space as independent organizers of demonstrations, meetings, parades, etc.

Lviv was primarily the center of the Polish Sokół movement, both because of the assistance of the authorities and because of its demographics. The Ukrainians managed to build their own stadium ("Ukrainskyi Horod") only in 1911, which once again confirms the existence of the Ukrainian movement in Lviv as a network of national enclaves.

The most active periods for Polish Sokółs were May and June, when they started the "new Sokół year" and reported about the previous one, and when the weather was favorable for outdoor sports events. In addition, these are the traditional anniversaries of the Third May constitution and the feast of Corpus Christi, important dates in the Polish patriotic calendar. This period also marked the end of the school year, when pupils could be more actively involved in gymnastic movements under the supervision of their elders at the stadiums on ul. Cetnerówka or ul. Łyczakowska. The opening of the season traditionally included a divine service, speeches, exercises, games, and a solemn march "to the city". Besides, the festival season had also to begin in which the Sokółs took an active part as well.

Over time, new ways were invented to attract more spectators who bought entrance tickets to watch sports performances. For example, a demonstration of the cavalry unit in the uniforms of the Polish Lancers in June 1911, or horseback riding exercises "for ladies." This is in addition to running, saber fights, and the construction of "living pyramids" by athletes.

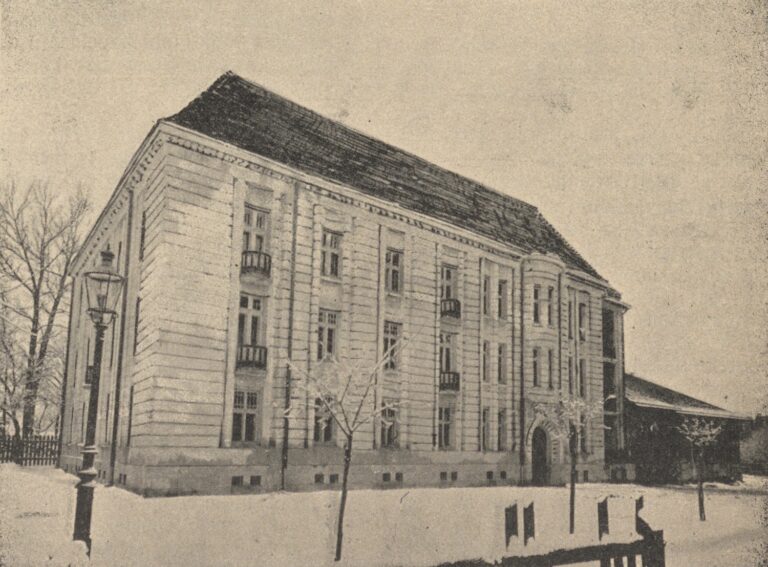

Opening of the Sokół-III branch in the Żówkiewskie district

Various consecrations were also held pompously and on a massive scale. In 1909, another branch of the organization, Sokół-III (Żówkiewskie district (III) of the city), consecrated its standard. At first, members of the society from Lviv and the vicinities gathered in the hall of the central organization of the Sokół-Mother building. Then, accompanied by an orchestra, they went to the Żówkiewskie suburb. They were met by local Sokółs "at the railway" and went together to the Sokół-III stadium on the grounds of the former barracks located on ul. St. Martin. Local residents, members of the Skała and Gwiazda societies, volunteer firefighters from the Sokół society, firefighters from Zamarstynów, and others gathered at the stadium. Archbishop Józef Bilczewski celebrated Mass at a special altar, saying in his sermon that there was a need to "go into battle, like Żółkiewski or the Bar Confederates, for a better future and liberation." There were other speakers who said, among other things, that the Sokół was a brotherhood of the whole nation, regardless of class or origin, i.e. very modern mobilization things.

After the service and speeches, the ritual of "nailing" the standard pole began. The nails were driven in by Archbishop Józef Bilczewski, Lviv Vice President Karol Epler, representatives of the Sokół, the marshal of the Lviv County Council Leopold Baczewski, whose family business was located just outside the Żówkiewskie suburb, and other dignitaries. Then they entered their names in the commemorative book and eventually handed the standard over to its bearer. All of this was accompanied by numerous references to the Motherland and the Virgin Mary, the Queen of the Crown of Poland. From the stadium, the members of the society went to the Sokół-III building, where they held a parade, sang the Polish national anthem, and brought the standard into the building. The streets of the Żówkiewskie suburb, along which the demonstrators were moving, were decorated with greenery and flags.

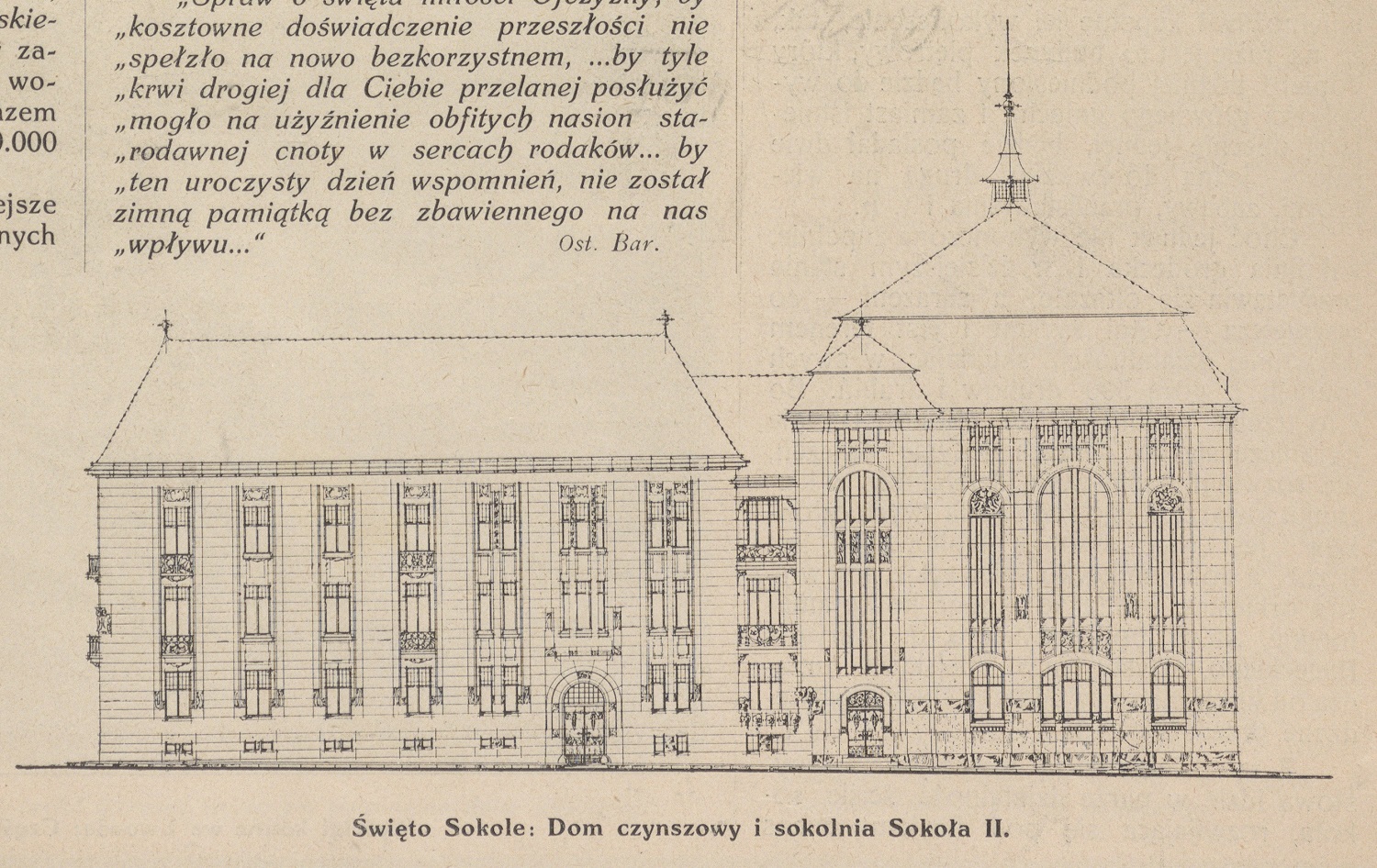

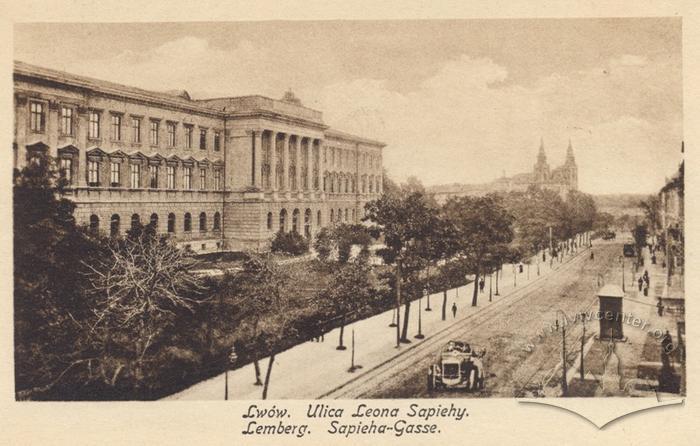

Opening of the Sokół-II branch near the main railway station

A similar scenario was used to consecrate the standard and premises of the Sokół-II branch on ul. Szeptyckich (now vul. Fedkovycha 30-32) on 6 June 1909. From 7:30 to 8 a.m., guests arriving at the railway station were greeted. At 9 a.m., a meeting began in the halls of the Mother-Sokół and the Sokół-II on ul. Szeptyckich. At 9:30 a.m., two groups of the Sokółs went from there to the event venue located on ul. Leona Sapiehy, opposite the Konarski School. Here, at 10 a.m., a field mass began, followed by speeches, the consecration of the standard, nailing, entry in the commemorative book, and the handing over of the standard to the bearer. Then there was a solemn march along ul. Szeptyckich, ul. Szumlańskich, ul. Gródecka, ul. Sapiehy, and ul. Szeptyckich again to the Sokół-II building. It was only after all of this that the consecration of the building itself began.

At 4 p.m., the guests could attend (for a fee) "sports activities" in the open space on ul. Sapiehy opposite the Konarski School. At 8 p.m., there was a party with dancing, a choir, and an orchestra performance in the building on ul. Szeptyckich.

The support of the authorities and local elites was manifested not only in their attendance at Sokół celebrations. For example, when members of the Lviv Polish Sokół were preparing for a shooting competition to be held in Krakow in 1910, the Rifle Association allowed them to use their shooting range. Young people from Lviv schools were encouraged to use the Sokół's stadiums, where the students were supervised and thus "educated" in the right spirit. Even school patriotic events, such as various recitations and singing on the 3rd of May, could be held in the Sokół premises.

Places of the Ukrainian Sokil

In principle, the activities of the Ukrainian Sokil did not differ from those of its Polish counterparts, adjusted for the scale and the fact that they had to work in their national "enclaves." Nevertheless, it was possible to rent a hall or even a whole pond. Thus, in winter, the Morskie Oko (Sea Eye) pond was decorated with blue and yellow flags, and people organized their own "festivals" and rented out skates. They also would arrange festivities in the suburbs (for example, at Zboishcha) and return to the city afterward, sometimes even organizing torchlight processions. Traditionally, the calendar was also different: for Ukrainians, the Taras Shevchenko commemorations in March and the Intercession of the Holy Virgin in October were important dates. An example of how successful such activities could be even in unfavorable political conditions was the so-called "Ukrainskyi Horod" (Sokil-Father stadium). The land for this stadium was purchased by raising funds even from Ukrainians in emigration.

In contrast to the regular Polish gatherings, Ukrainians held only two provincial gatherings during the period of autonomy, in 1911 and 1914. If we carefully study the rhetoric of the 1914 action organizers, it was a mobilization of the entire national resource and, in fact, a challenge to the Poles.

Thus, Poles and Ukrainians, while "building societies", simultaneously formed prototypes of their own armies, which proved themselves during the Great War and after it, during the battles for Lviv.