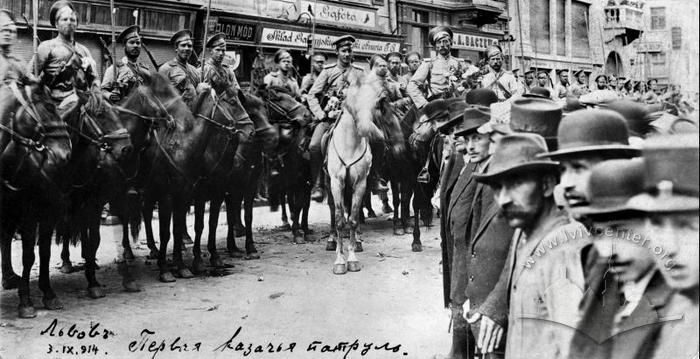

From September 3, 1914, to June 22, 1915, Lviv was under Russian occupation. As early as the first day, Russian flags were hung on government buildings. Signs in government institutions were also quickly replaced; now they were in Russian and Polish. The clocks were changed to St. Petersburg time; then the Russification of the space was continued through the replacement of shop signs and the transition to the Russian language in education and administration. True, the pace of Russification after the first "surge" noticeably decreased – until late February 1915, when signs in Russian began to be attached on top of street signs with Polish street names.

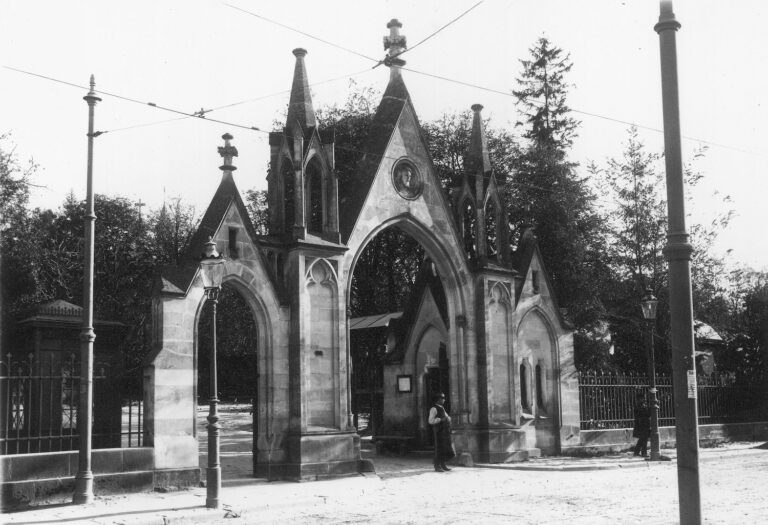

Handing over the symbolic keys of Lviv. Tadeusz Rutowski, vice president of the city and representatives of the Russian army at the Lychakiv slingshot in Lviv

A specific feature of the Russian occupation was the Russians’ attitude to the region, to its population, and to their own role in this war. While the Austrians at least did not consider Galicia to be a German land, the Russians, on the contrary, interpreted their occupation as the liberation of the "primordial lands of Russia", inhabited by alien Poles and "irregular Russians", who had to be corrected through education, the language of the press and business administration, as well as deportation.

As for the possibility of public demonstrations, Lviv, in a certain sense, seemed to have returned to the condition it was in after the Spring of Nations in 1848 and to the neo-absolutism established in the 1850s. Publicly, it was only allowed to demonstrate one's religiosity and loyalty to the monarch, this time to the Russian one. Everything was clear with the monarch (the Russians did not count on mass loyalty in a "Polish city"); in terms of church celebrations, however, when religion could tell a lot about nationality, Roman Catholic events were automatically considered Polish. Obviously, it should be taken into account that the society in 1914 was "politically more mature" than 60 years before, relying on the experience of autonomy as part of Austria-Hungary. But only the Roman Catholics had such opportunities as the hierarchs of the Greek Catholic Church were repressed, the attitude towards the Brest Union of 1596 on the part of the new government being sharply negative. The Jews, after the pogrom of September 27, 1914, also tried not to attract too much of the occupiers’ attention.

When national manifestations were actually reduced to church rites, the calendar became important again. In this regard, the Poles and Ukrainians in Lviv seemed to have switched places since now the Julian calendar was official, while the Gregorian calendar was purely religious. Now it was the Poles who were forced to preserve their identity only "in the denomination", since other options were closed.

* * *

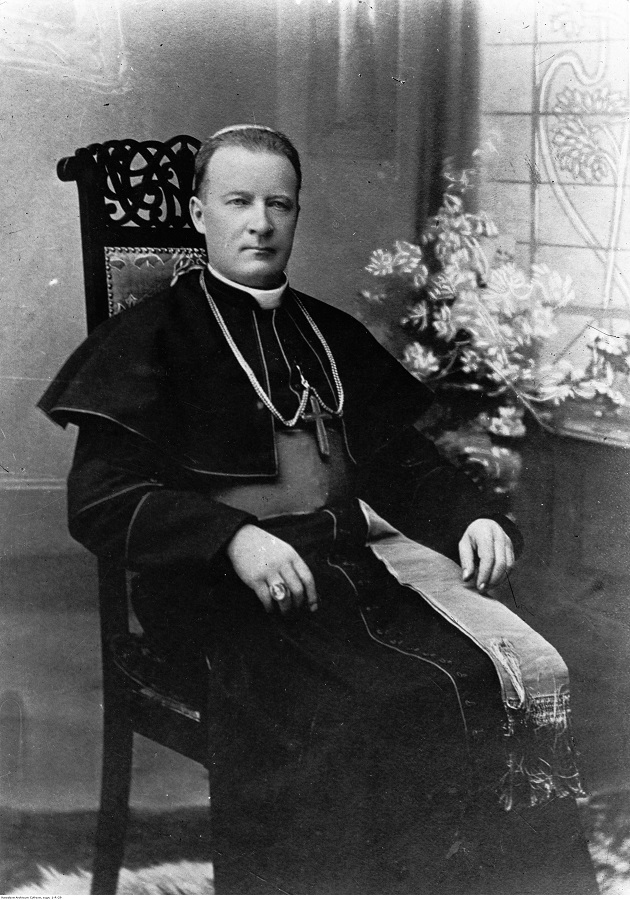

The first mass event after the beginning of the Russian occupation was a solemn service held on September 14 in the Latin Cathedral on the occasion of the election of a new Pope. In contrast to the usual "broad representation" of officials, military, politicians and public figures, this time the cathedral was attended only by "the clergy and the public", although it was Metropolitan Józef Bilczewski himself who celebrated while the city choir was singing.

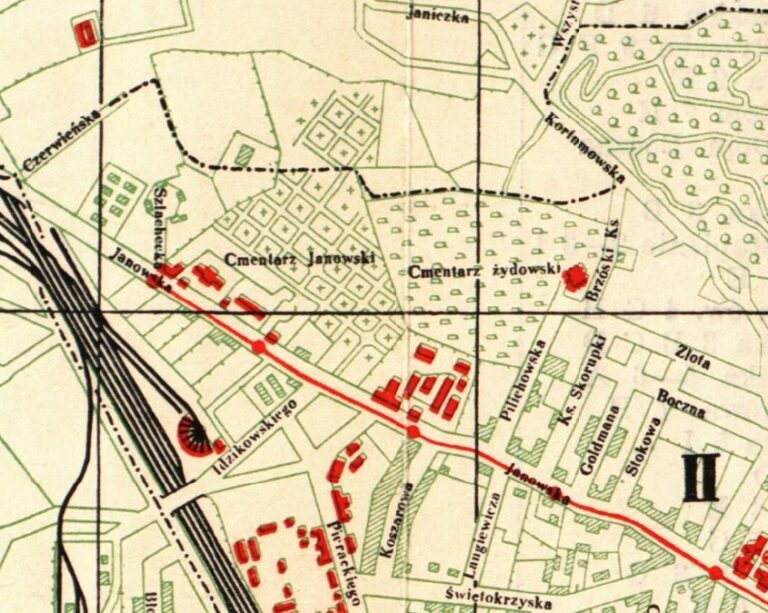

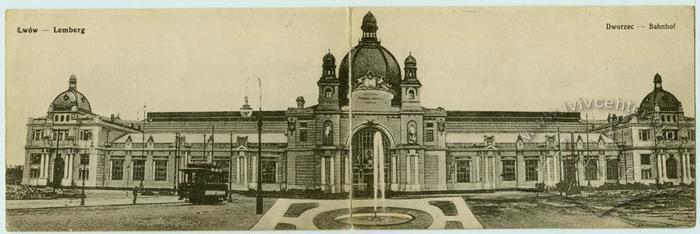

The Russians also "appeared" in the public space of Lviv through religious ceremonies, mostly funerals. On Wednesday, September 16, the body of General Sergey Vannovsky, who had been wounded and captured and died in a Lviv hospital on September 10, was ceremonially exhumed. At 9 a.m. on that day the body was dug up at the Janowski cemetery, put in a carriage and taken to the railway station. The carriage was followed by the widow and the higher military command as well as by the guard of honour consisting of infantry and Cossacks. At the station, Orthodox priests sang funeral dirges over the late general and sent his body to St. Petersburg by train.

Later, the press noted two more interesting funerals. On February 19, 1915, a funeral service was conducted over the body of a Russian colonel on ul. Piekarska; then the coffin was again sent to the station accompanied by an orchestra, officers, infantrymen, as well as Don and Siberian Cossacks. In April, a downed pilot was buried: the farewell ceremony was held in the Polytechnic building, turned into a hospital; then the coffin with the body was taken by car (which, actually, was a curiosity) to the newly established Orthodox cemetery (now the Hill of Glory).

On December 19, the tsar's birthday (according to the Julian calendar), house owners were instructed to decorate their façades and balconies. Mostly this decoration consisted in hanging a small Russian tricolor. The Russians held a military parade on ul. Podwale and solemn services in Orthodox churches. Similarly, on Christmas and Easter, according to the "old style", the Russian administration organized celebrations mainly for "their own" soldiers and officials.

While the Russians were taking the bodies of their high-ranking officers to Russia, the Polish press lamented over a small number of people attending the Lychakiv cemetery on memorial days. On November 1, 1914, after a memorial service in the Latin Cathedral, "very few participants gathered for the march to the cemetery." In addition, the graves of "prominent citizens and figures" were left without the usual wreaths and lamps that year. After all, funerals of Polish public activists and politicians ceased to be crowded events, now they were attended mainly by relatives and colleagues of the deceased.

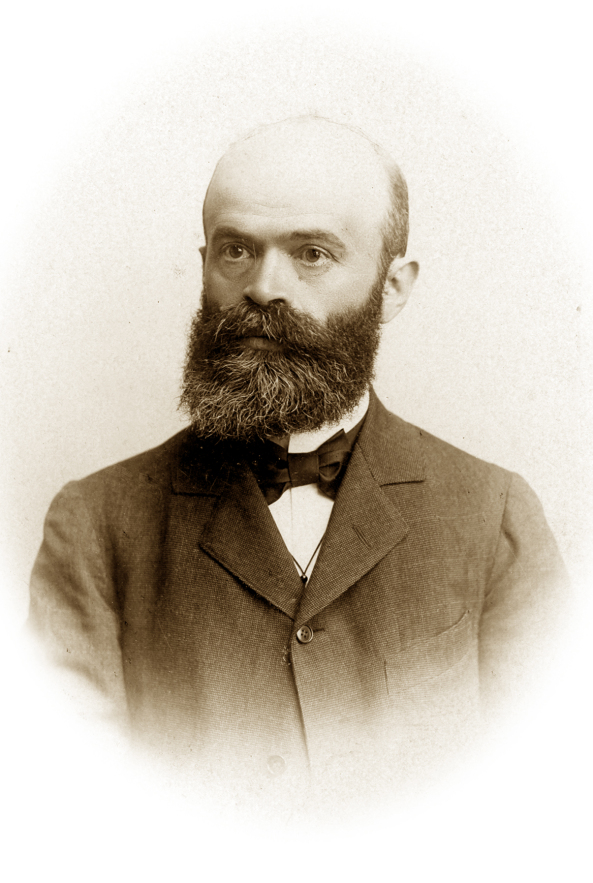

The Ukrainians were not an exception in this series of "funeral representations": in January 1915, when politician Mykhailo Pavlyk was buried, a Ukrainian mass event took place. In view of the fact that the occupying Russian administration was very hostile to Ukrainophiles, the very fact of a mass funeral can be considered a political event.

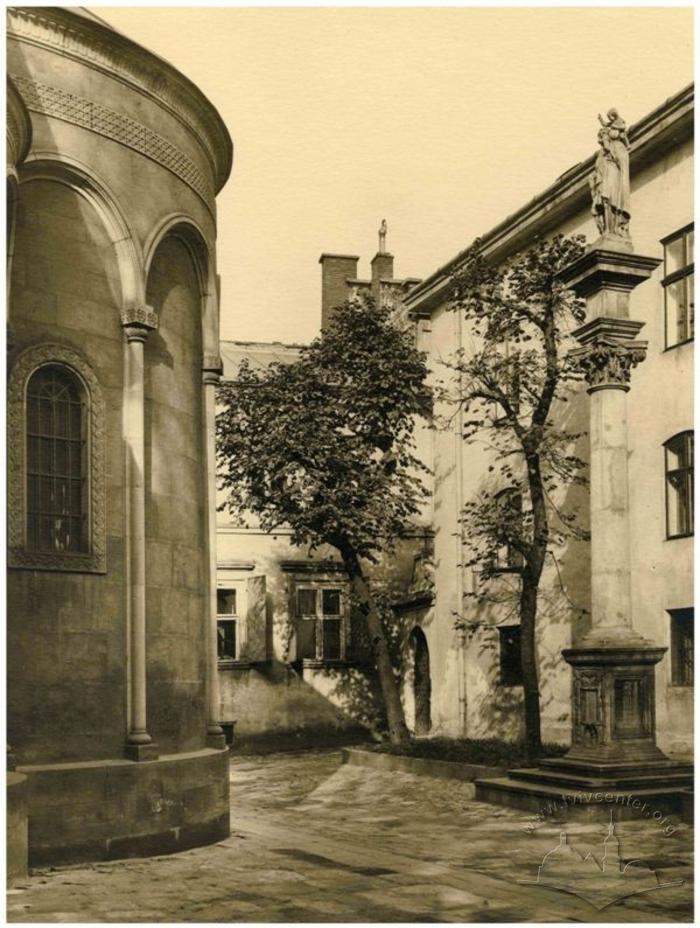

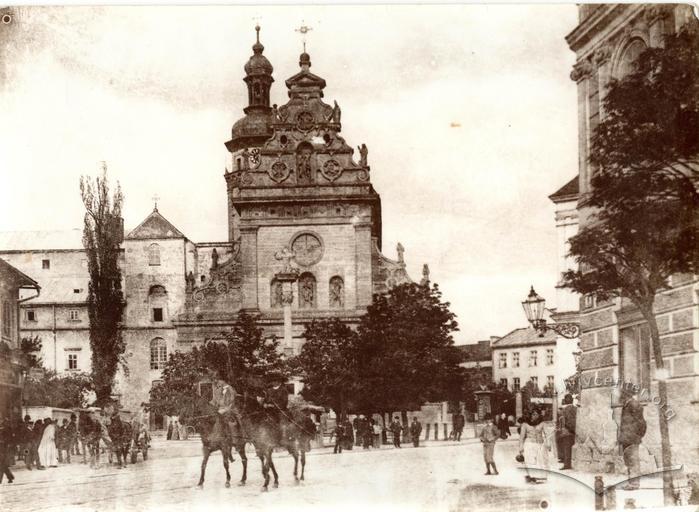

The first mass event during the Russian occupation, which remotely resembled the former pompous celebrations, was the "merchants' holiday" on December 8. During the period of Galician autonomy within the Austrian-Hungarian empire, when it was possible to celebrate the anniversary of the November Uprising and to honour Adam Mickiewicz throughout November, this "corporate holiday" in early December with its reference to the history of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was not very popular. The "merchants' holiday" was one of the many dates when it was possible to recall the history of independence, in particular the history of guilds in Lviv before the "partition of Poland"; early December, however, clearly did not contribute to its popularization. Nevertheless, in the new conditions, it was the merchant traditions that did not threaten the state power, and the Marian holiday, which coincided with the "Lviv merchants" jubilee, that made the celebration of "Polish history" possible. Guilds, societies, clergy gathered for the solemn divine service conducted by Metropolitan Józef Bilczewski, shops were closed, while the statue of the Virgin Mary on pl. Mariacki was decorated with additional electric illumination.

Even the name days of Józef Bilczewski and Armenian Archbishop Józef Teofil Teodorowicz in March 1915 were interpreted similarly. The magistrate members – those who remained in Lviv in September 1914 – came to the Cathedral separately. It was even possible to hold something like a rally on pl. Kapitulny, where Tadeusz Rutowski, who acted as the president of the city of Lviv, told Józef Bilczewski: "We stand by you and we want to obey your instructions." Actually, it was an almost verbatim repetition of the formula "we stand with you and we want to stand" with which the Polish aristocracy greeted Francis Joseph during his visits to Lviv. This was the first appearance of the City Council in this capacity at such an event; before, the city president and the magistrate in general focused exclusively on economic issues, in contrast to the period of autonomy, when the City Council always sought to engage in "big politics" on a national scale.

Archbishop Teodorowicz was congratulated by the same respectable gathering in the Armenian Cathedral. "Polish financial institutions" joined these congratulations separately, demonstrating "national solidarity" in this way.

So, as of the spring of 1915, the Polish politicians of Lviv found a model of coexistence with the Russian authorities in which public life, although it moved into the sphere of "religion", had clear signs of nationalism.

It is important to remember that all this happened against the background of arrests and deportations of "suspicious characters", including hierarchs of the Greek Catholic Church, such as Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi. Press reports about prisoners, the ban on the sale of alcohol and the threat of cholera became completely emotionless, and most of the news consisted of reports about looting, theft and food shortages. Even attacks by stray dogs, which happened frequently and regularly, were described as something quite familiar and understandable. The former times could only be reminded of by the news about the illegal cutting of parks (for firewood) or the mention of the May 3 constitution (but not about the uprising or examples of the struggle against Russia). In May, articles were added to this depressing list about refugees from the Carpathians who fled either to Lviv or through Lviv further east from the frontline.

On March 22, on the occasion of the capture of Przemyśl by the Russians, by order of the Governor-General, processions with flags and portraits of the tsar and the commander-in-chief appeared in the city, accompanied by military bands.

On April 22, 1915, Tsar Nicholas II visited Lviv. In the morning, he arrived by train in Brody, where he received a report on military operations and had breakfast. At 1 p.m., accompanied by the chief of the general staff Nikolai Yanushkevich, he left by car for Lviv, stopping on his way near the mass graves of Russian soldiers.

He arrived in Lviv at 5 p.m. and was welcomed by the governor-general, count Georgiy Bobrinskiy. On the streets, as was customary in cases like this, he was greeted with shouts of "hooray" by a crowd of curious people as well as an orchestra and Russian soldiers. First the tsar visited the garrison church at Klepariv, where the Archbishop of Volhynia Yevlogiy conducted a divine service; then he came to the military hospital in the premises of the Academic Gymnasium, where Grand Duchess Olga Aleksandrovna was listed as a sister of mercy.

At 8 p.m., the tsar with his retinue (his motorcade consisted of 16 cars in total) arrived at the governor's office, where a crowd was already waiting, "greeting him with shouts of enthusiasm." Nicholas II's speech from the balcony was succinct: "Thank you for the warm welcome. May there be a single, strong, indivisible Russia. Hooray!" Then a dinner was held in the building, with representatives of civil and military authorities invited. On the following day, the tsar left for Przemyśl; on his way back he spent a night in Lviv again, having visited the Vysokyi Zamok (High Castle) Hill before. After the visit, information appeared in the press from time to time about a monetary donation from the tsar for the benefit of the city, which was disbursed through charitable initiatives.

In May 1915, the "vows of King Jan Casimir" (dedication of Poland to the Mother of God) were solemnly celebrated in the Latin Cathedral, while traditional "majówkas" were held in all the churches of the city. They were held daily and reported on in newspapers; considering the fact that, officially, it was still April (according to the Julian calendar), Polish religious rituals in May were becoming even more Polish.

The anniversary of the constitution was also solemnly celebrated in the cathedral on May 3, when the service ended with a "song of prayer for a better future for Poland."

Thus, during the whole of May, with concerts of church music and the decoration of houses for the Green Holidays (popular name of the Pentecost), Lviv’s Poles prepared for the celebration of Corpus Christi (when the so-called “chicken king” was traditionally elected, members of the Rifle Association marched through the city, and almost all representatives of the City Council were involved in the celebrations).

In 1915, everything was much more modest, but, nevertheless, it was described as a manifestation of "the whole of Catholic Lviv." Members of the City Council took places of honour in the Latin Cathedral, pl. Rynok was filled with processions from all the churches of Lviv, and four altars were built in the center of the city (one was opposite the Jesuit church, two were opposite the houses on pl. Rynok and another one was in front of the City Hall gate). A mass was held from 9 to 10 a.m., then there was a procession from one altar to another. The clergymen were followed by members of the "riflemen brotherhood" with a standard — an unusual phenomenon for occupied Lviv, – representatives of the University and of the Polytechnic, members of the City Council and the public. Even a "public guard" formed by members of the fire department was involved.

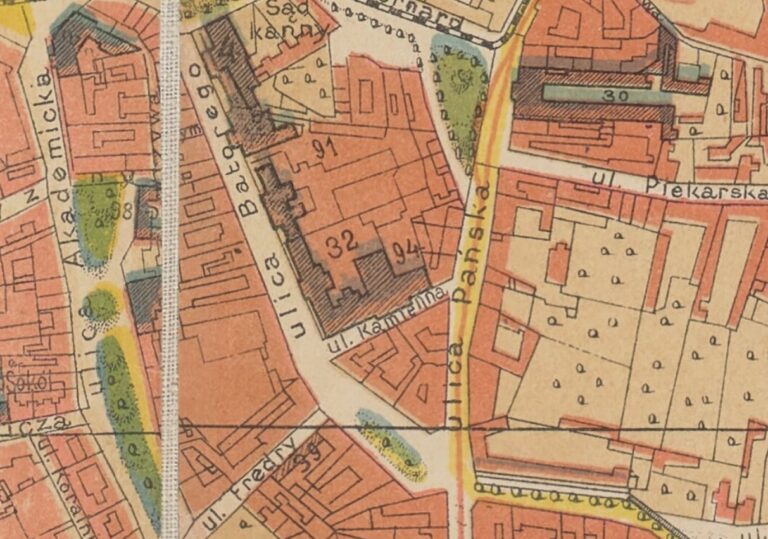

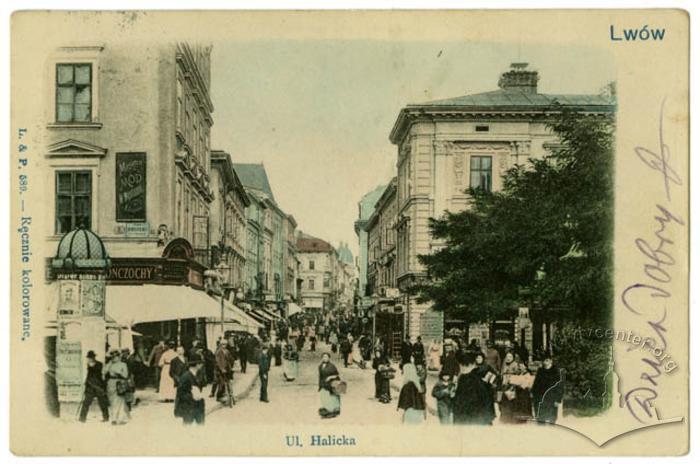

On the following Sunday, May 24, according to the old style, another Corpus Christi celebration took place under the leadership of Józef Bilczewski, this time in the Bernardine church. The procession passed from pl. Bernardyński through ul. Pańska, ul. Kamienna, ul. Batorego, pl. Halicki and pl. Bernardyński again. The day before, the residents of the houses along the route were urged to display icons and candles in their windows and to decorate their balconies with carpets and flowers.

Later, when June began, the patriotic Polish public focused on Catholic devotions to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, not betraying their tactics of emphasizing religious and calendar differences. In the end, the Russian troops left the city and it is not known whether this approach would have brought any results in the long run.

* * *

Thus, after repressions by the occupation authorities, the only legal way of manifestation in Lviv (except for welcoming the Russian tsar and funerals of Russian officers) were Roman Catholic religious celebrations. They allowed the Poles to emphasize their identity through their denomination and, in addition, were celebrated according to the Gregorian calendar, while the Russians had made the Julian calendar official. Actually, the Poles acted as the Greek Catholic Ukrainians had done before.

Under these conditions, the Poles of Lviv managed to attach a maximum of national meaning to church events. At first they held these events in a very cautious way, limiting themselves to solemn religious services, but after six months of the occupation processions were already organized in the center of the city, though, true, without any political slogans, speeches or proclamations. It is possible that this freedom was due to the importance of the Polish question in this war, hostilities in the Kingdom of Poland and anti-German component of the Polish movement. The fact remains that Polish politicians managed to use even these limited opportunities for their own representation.