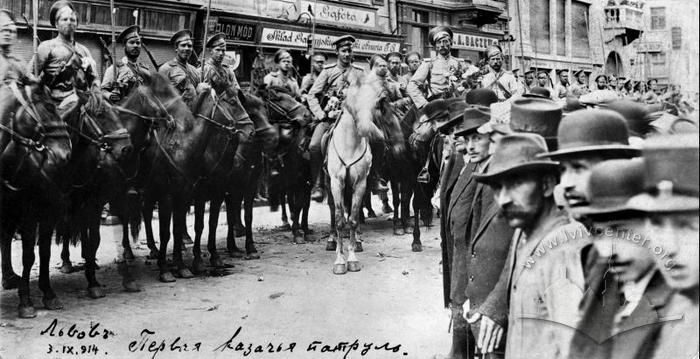

After the proclamation of a "revived Poland" in November 1916 and the formation of the Central Council (Rada) in Kyiv in March 1917, there was an understanding that there would be no return to the former agenda. Lviv ceased to be both "the capital city of the freest region of divided Poland" and, later, the main center of Ukrainian political life. The press paid much more attention to the revolutionary events in the Kingdom of Poland or the Ukrainian People's Republic and was concerned with the future of Chełm Land, peace negotiations between the great powers or the Bolsheviks’ coming to power in Petrograd (St. Petersburg), while local politicians had less and less opportunities to show themselves.

All this does not mean, however, that Lviv residents abandoned the traditional "political calendar." On the contrary, they tried, although in a rather modest way, to carry out all the usual "tours" that had been carried out during the times of autonomy, as well as those invented during the Great War.

Celebrations associated with the imperial family

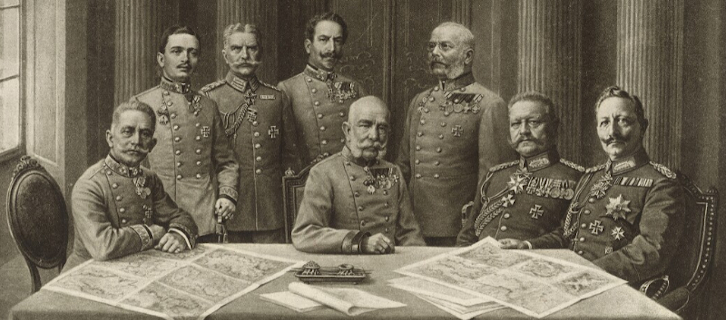

The Austrians were traditionally active in the urban space through celebrations related to the ruling dynasty as well as through the visits of distinguished guests. On November 21, 1916, after 68 years of reign, Emperor Francis Joseph died. The city, like the entire empire, plunged into mourning: black flags were hung at buildings, theater performances and film screenings were cancelled as well as classes in schools, music was banned in restaurants. In addition to religious services in all churches, almost every organization, institution or society held a special mourning meeting.

After that, festive services were celebrated on the occasion of the new emperor Charles’ accession to the throne; the birthdays, name days and anniversaries of the new imperial couple became public holidays. Like, for example, the birthday of Empress Zita of Bourbon-Parma on May 9. The birthday of the main ally, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II, was also celebrated in Lviv on January 27 with solemn services.

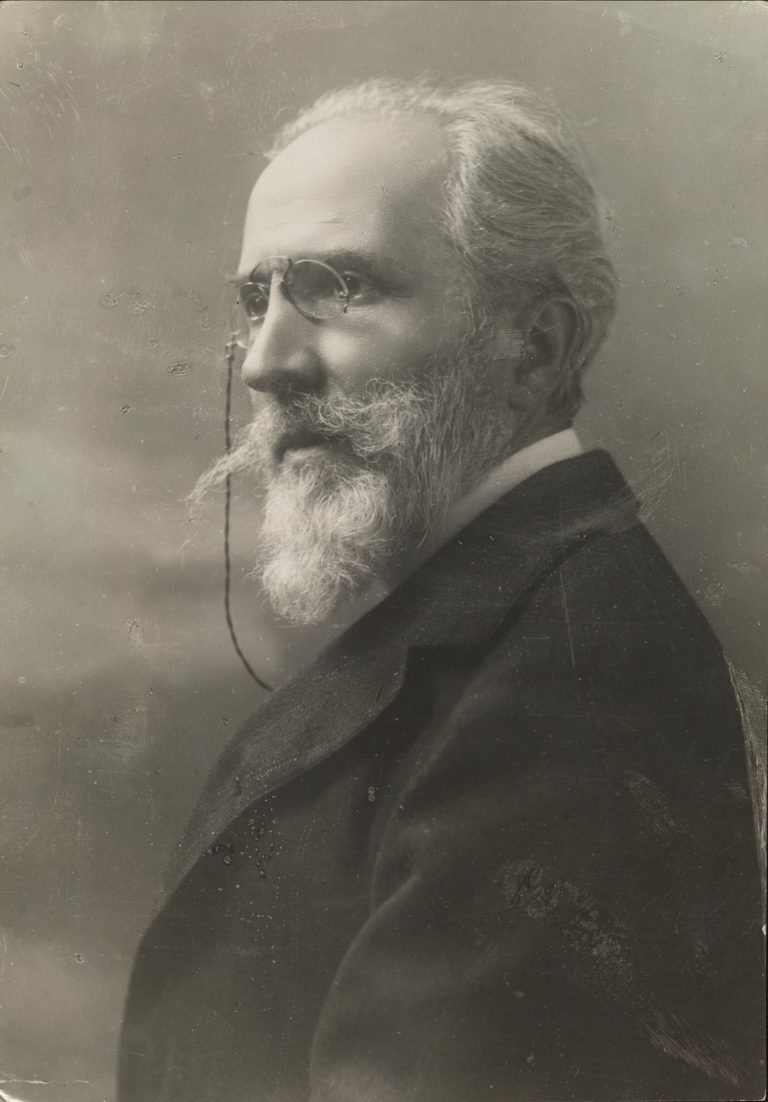

As for the visits of dignitaries, they were connected either with military actions, when, for example, on September 4, 1917, King Friedrich August III of Saxony stayed in Lviv for several hours on his way to the frontline, or with visiting the wounded. Thus, in December 1916, Lviv was visited by Archduke Karl Stephan of Austria. In an institution for the blind on ul. Św. Zofii, he met veterans maimed in battles, then he had dinner with the army commander Eduard von Böhm-Ermolli and archbishops Józef Bilczewski and Józef Teofil Teodorowicz. The visit of Archduke Leopold Salvator in early April 1917 was essentially an inspection of the same kind. In all these cases, it was up to army officers to meet and escort the guests while the public or local politicians were not expected to participate.

Ukrainian mass events in Lviv

The Ukrainian community of Lviv also combined old, pre-war rituals with new ones related to the war or current events. Epiphany was celebrated according to the Julian calendar, special events were held on St. Andrew's Day in honour of Metropolitan Sheptytsky, a solemn procession was organized for the feast of the Eucharist (Corpus Christi), according to the "old style" as well.

New dates in the "patriotic calendar" were the anniversary of the battle on Mount Makivka, April 29 — May 1 (although the solemn events were held not in Lviv but at the battle site) and the anniversary of Ivan Franko's funeral. According to the organizers' design, visiting Franko's grave at the Lychakiv cemetery in late May was supposed to be a "national manifestation"; however, it all was quite modest, limited to speeches, choral singing and laying of flowers. Meanwhile, Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky, who was returning from Russian exile, celebrated a mourning service in Kyiv on the same occasion.

On May 1, 1917, a meeting of socialists was held in the People's House where the national contradictions between the Poles and Ukrainians were so clearly manifested against the background of talks about the working people solidarity that the newspaper Dilo called the event "a mistake of the Ukrainian idealist Hankevych, which was used by the Polish imperialist Herman Diamand."

In spite of the fact that Ukrainian politicians regularly protested against the government's plans to grant Galicia broad autonomy or to annex Chełm Land to the Kingdom of Poland, the faith in Austria as the main arbiter remained strong. So was also the hope that it would be possible to deal with the Poles through complaints and appeals to Vienna. That is why strange things happened: during the mourning for Francis Joseph, the Ukrainians were called to attend memorial services, to hold special events in schools and societies and to hang black flags. At the same time, however, they had to remember that the decision of November 5, 1916 on the "restoration of Poland" was taken by the deceased emperor. When the University’s Senate refused to attend or delegate someone to the memorial service in the Greek Catholic church of St. George, "because everyone attends Roman Catholic churches," the newspaper Dilo called on the authorities to react to this "demarche."

Polish mass events in Lviv

The situation in Polish politics was also ambiguous. On the one hand, the revival of Poland had been allegedly announced and this was a reason for joy, while on the other hand, all this enthusiasm was still controlled by the Austrian authorities in Lviv. Later, in July 1917, when the Polish legions in Warsaw refused to swear allegiance to the king (especially since the person of the latter had not yet been defined), and the German command began detaining the legionnaires, the situation became quite uncertain.

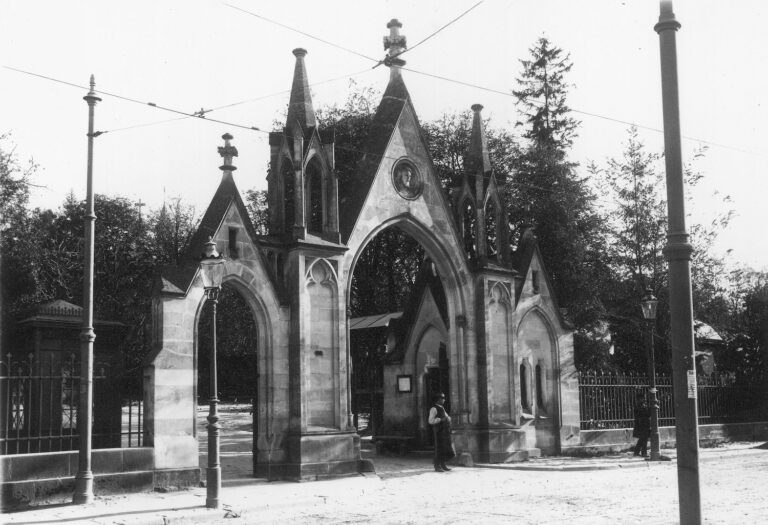

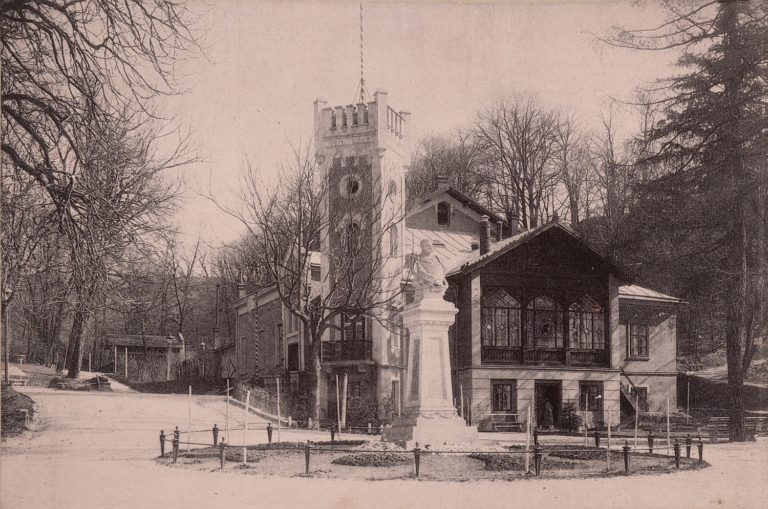

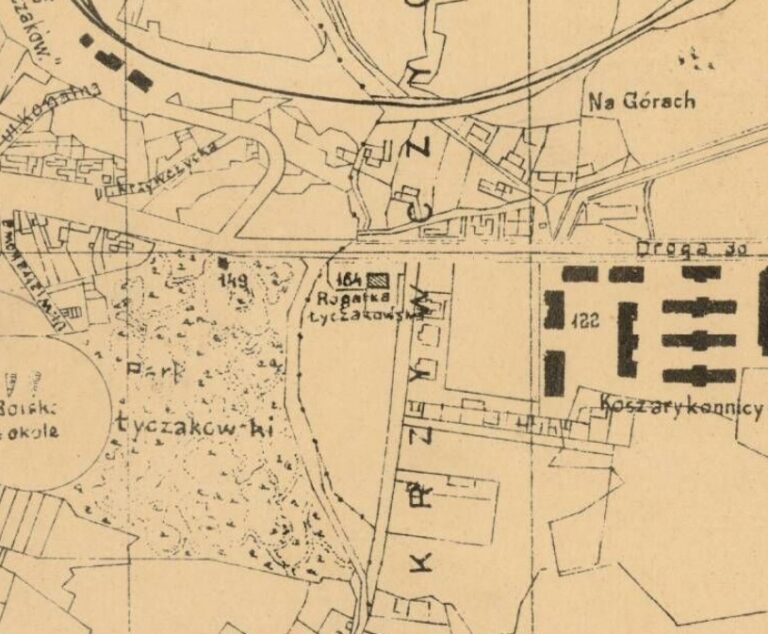

Nevertheless, the Poles, although modestly, held their traditional "tours": the "bourgeois" holiday of the Lviv merchants on December 4, the commemoration of the November Uprising and the January Uprising, the anniversary of the Battle of Racławice, the constitution of May 3, and the 100th anniversary of Tadeusz Kosciuszko's death. As always, their "celebration geography" was wider than that of the Ukrainians: the Latin Cathedral, the City Theater, the Lychakiv Cemetery, the Strzelnica (shooting range), the Lychakivsky Park and the monument to Bartosz Głowacki.

Before the July crisis with the legions, when the Polish soldiers were still unequivocally positive characters, for the Austrian authorities as well, on January 7, 1917 Lviv was visited by the commander of the 2nd brigade of the legions, Józef Haller. The description of this visit in the press was stylistically very similar to materials dedicated to the emperor's visits: the brigade commander praised the city and its inhabitants, journalists reported on some common past of Haller and Lviv residents; the brigadier was being welcomed and inspecting. In particular, he visited the assembly point for legionnaires, the premises of the Polish Women's League, the Józef Piłsudski shelter and the quarters of the Legions. Newspaper reports of this kind, as well as an interview with Piłsudski, formed a specific agenda, not always connected with the reality of the Austrian province.

Over time, though, this agenda began to shape a new reality. On the second anniversary of the liberation of Lviv from the Russians, when solemn religious services were held in the city and buildings were decorated with flags, two flags, Austrian and Polish, were hung on the City Hall; before, an equality like this just could not exist. Another notable detail is that the Execution Mount began to be called Wiśniowskiego Hill in honor of the Polish rebel hanged there by the Austrians. Moreover, all this was happening against the background of the fact that in the Russia-ruled part of Ukraine, after the February Revolution, more and more administrative positions were given to ethnic Ukrainians. Even Ternopil, which was occupied by the Russian army, was managed by the Ukrainian historian Dmytro Doroshenko. All this forced the Ukrainians of Galicia to rethink their views on the Habsburg Empire or at least to look for new arguments in the confrontation with the Poles.

Starting from October 1917, after the successes at the frontline and the removing of the Russian army further to the East, the evacuated authorities began to return to Lviv. Therefore, on November 11, a meeting was held in the city hall "for the return of self-government" (which, in the end, anyway had no desirable outcome). While the Polish public welcomed this initiative, the Ukrainians disapproved it utterly. After all, if the City Council regained its old powers or new elections were held according to the old rules, without fixing the national quota, the Ukrainians would not be represented in power in one way or another.

So, like the previous years, 1917 in Lviv was a time of struggle for the "national future", which consisted mainly in fixing the "national past." However, there were also things in which this year differed from the previous one: for example, the return of the "citizens of the city" who had been deported by the Russians. Many of them were written about in the press, many were welcomed back by representatives of the authorities, societies or organizations, apart from relatives and friends. For example, on January 7, Dr. Jakub Diamand was greeted by representatives of the commissariat, the Jewish community and rabbis.

The most massive were the meetings of the President of the city of Lviv, Tadeusz Rutowski, and the Metropolitan of the Greek Catholic Church, Andrey Sheptytsky.

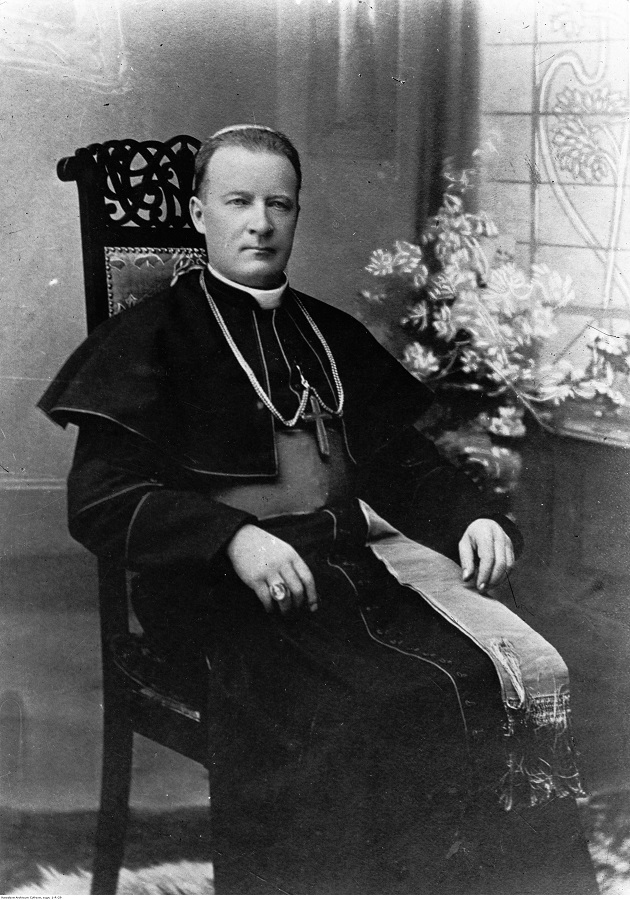

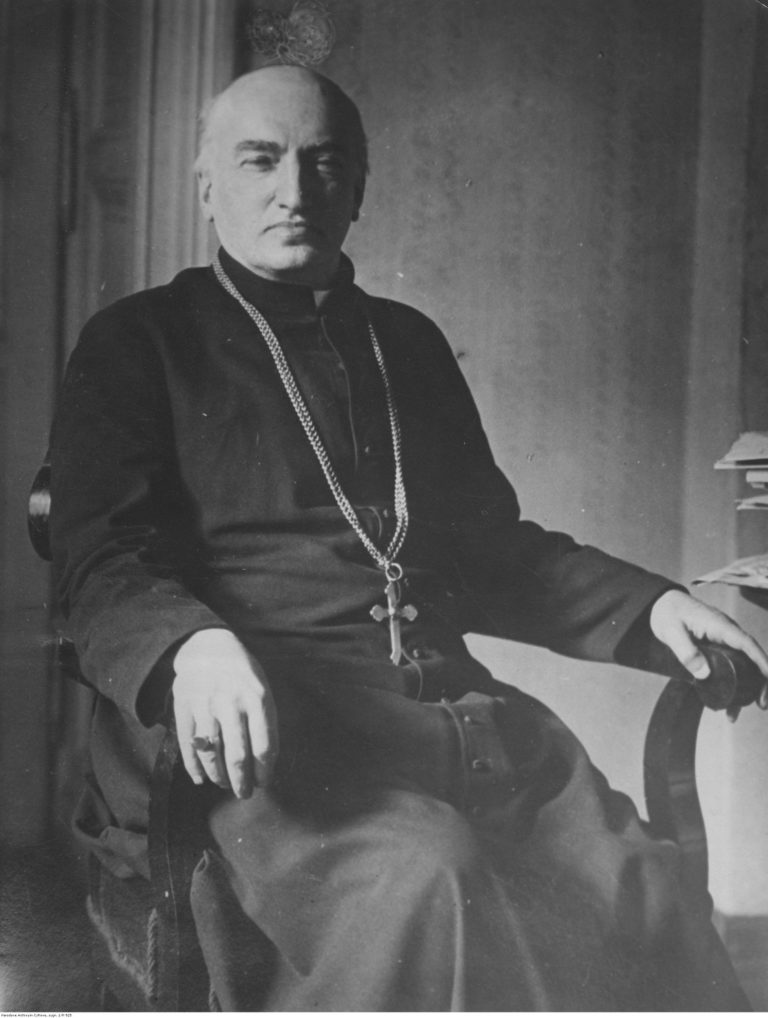

- Андрей Шептицький / Andrey Sheptyskyi

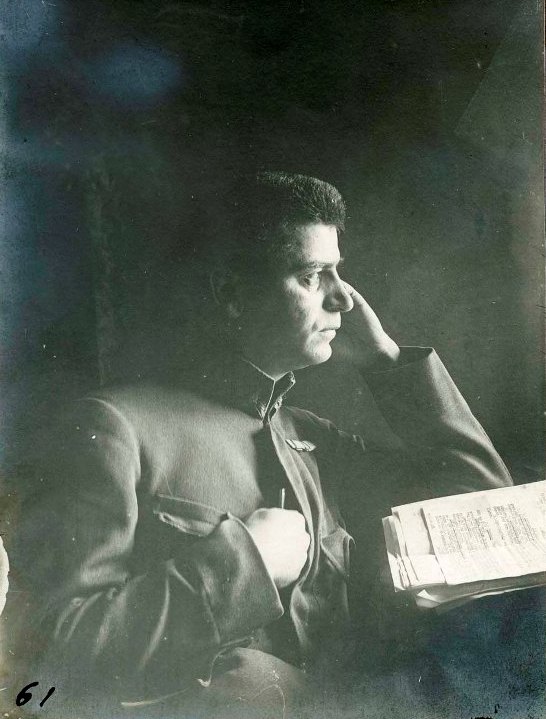

- Якуб Діаманд / Jakób Diamand

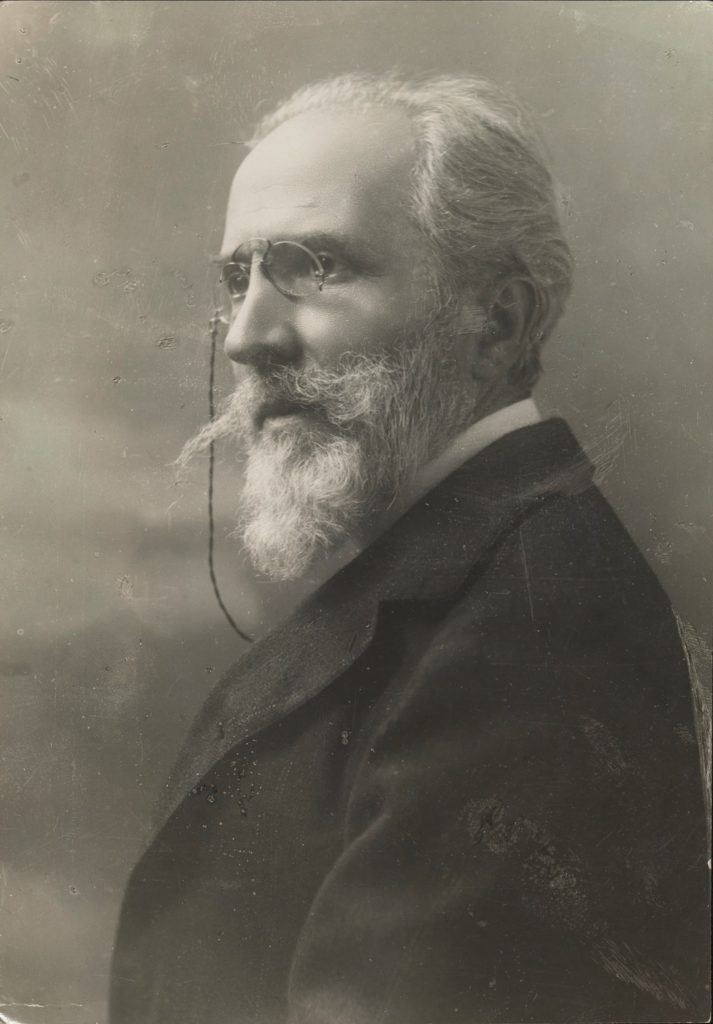

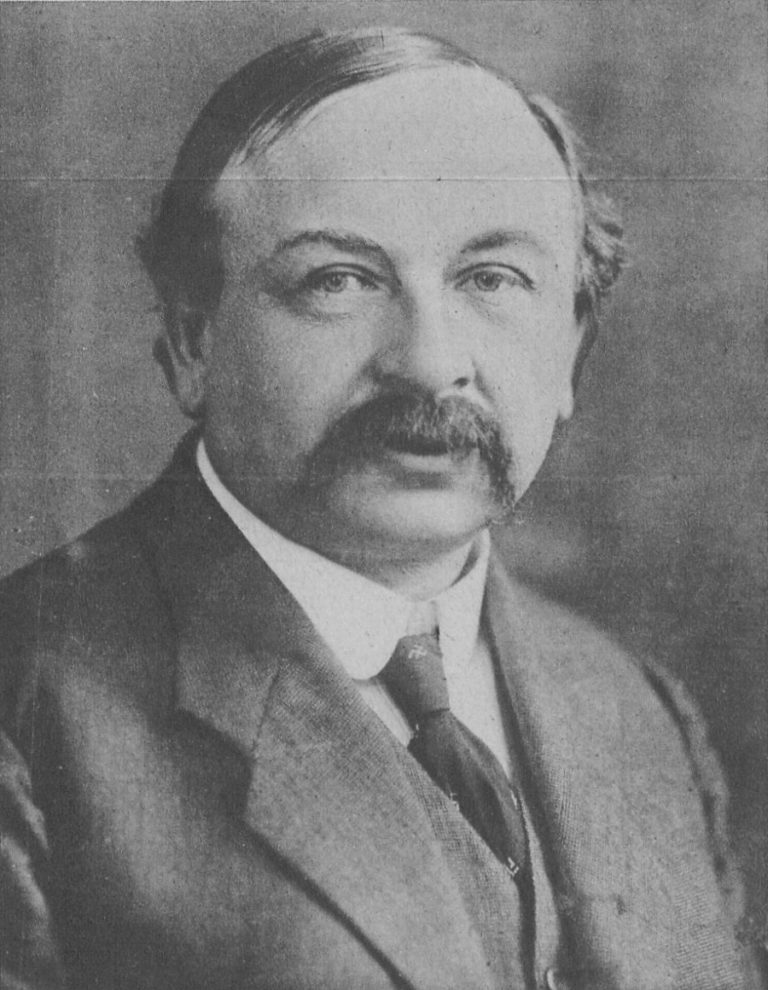

- Тадеуш Рутовський / Tadeusz Rutowski

Tadeusz Rutowski's return to Lviv

In the first half of January, information appeared that Tadeusz Rutowski would soon arrive in Lviv. The city promptly created an organizational committee for his solemn meeting. Patriotic organizations, such as the Rifle Association, called on their members to take part in welcoming the "outstanding citizen." However, there was a problem with schoolchildren, who were traditionally involved in mass events: because of the severe frosty weather, this time it was decided that children would not participate. The press also published materials dedicated to the merits of the "father of the city" before the Russian occupation and his work during the occupation; special posters were placed in the streets.

On February 1, 1917, Thursday, a delegation from Lviv left for Przemyśl to meet Rutowski, who was travelling by train from Vienna. Solemn morning services were held in the Latin Cathedral, the Armenian Cathedral, the Evangelical church and the Progressive synagogue.

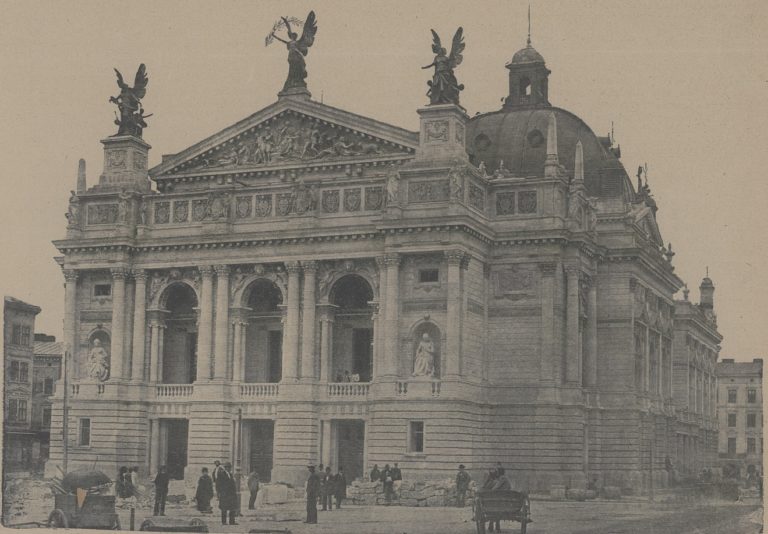

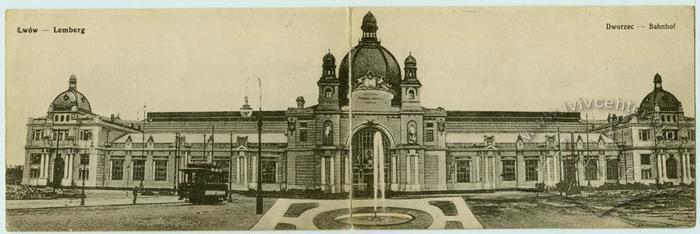

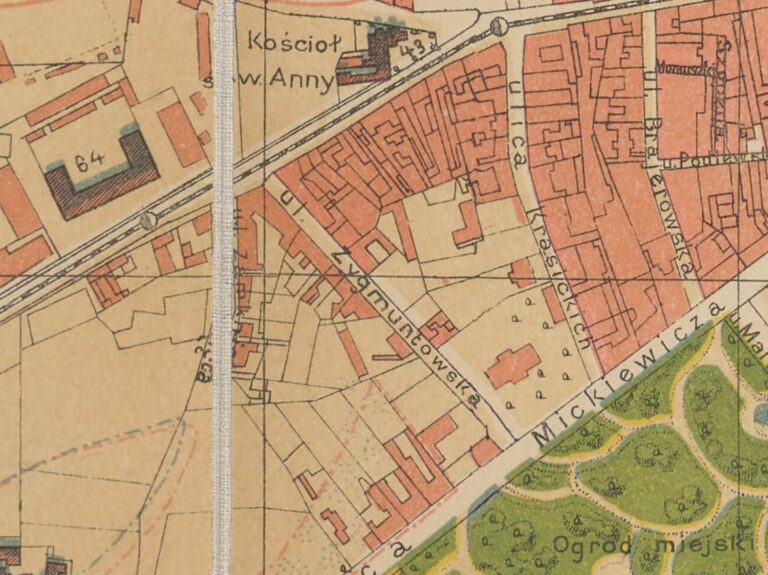

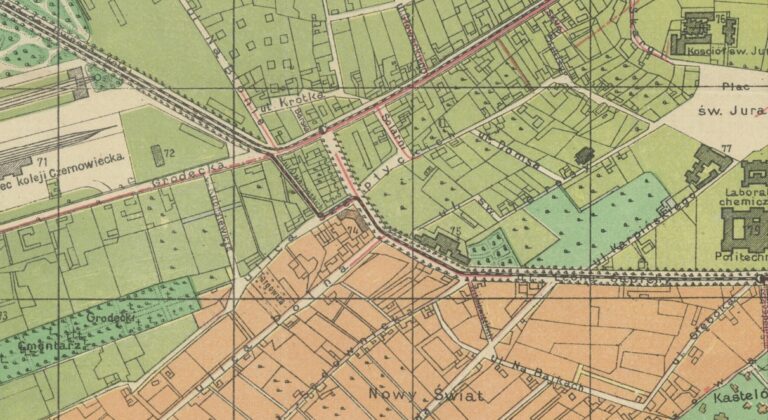

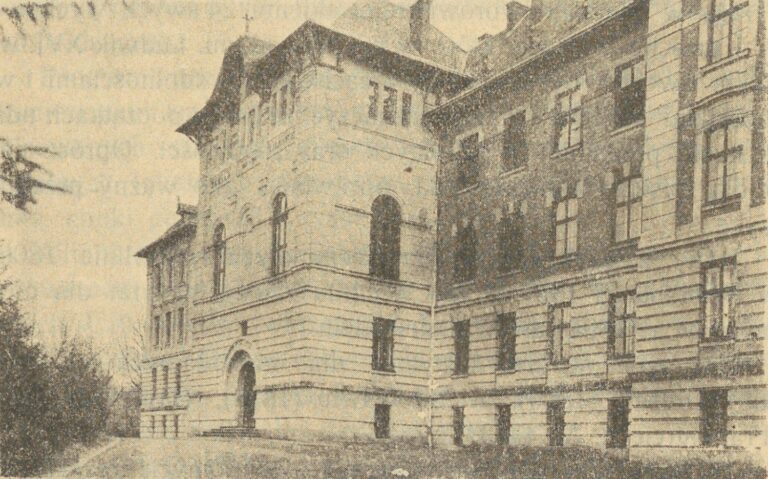

At 2:30 p.m., the train with Rutowski and the welcoming delegation arrived at the platform of the Lviv railway station. There he was greeted with shouts "Niech żyye!" ("Long live!"), speeches, flowers and music by the railwaymen's band. After greetings from the starosta Kazimierz Grabowski, Tadeusz Rutowski got into a carriage. A separate carriage was prepared for his family, local officials used others. The first two carriages were decorated with white and red ribbons, with the drivers wearing national Polish headpieces called "konfederatka". This whole procession, "slowly driving through the crowds of joyful Lviv residents", passed through ul. Gródecka (Horodotska) and ul. Żygmuntowska to the Sejm building, where Tadeusz Rutowski was greeted by representatives of the provincial authorities. Then they drove in a big "circle" around the city center: along ul. Trzeciego Maja, ul. Karola Ludwika near the City Theater, ul. Tadeusza Rutowskiego, renamed in his honor after his arrest by the Russians, pl. Mariański, ul. Kopernika and ul. Ossolińskich to the Loziński Palace. It was there that accommodation had been arranged for the Rutowski family.

The houses in the streets through which the carriages passed were decorated with carpets, flags and stickers. Order was ensured by the civil guard, firefighters, and soldiers of the Polish Legion.

On the following morning, Friday, February 2, about 700 people gathered in the assembly room of the city hall: representatives of the authorities, associations and organizations, as well as a large audience on the gallery balconies. Accompanied by the organizing committee members, Tadeusz Rutowski walked from his residence on ul. Ossolińskich along ul. Kopernika, pl. Mariański, ul. Rutowskiego and pl. Kapitulny to the city hall, where he was greeted with a bugle call from the tower. Then there were speeches and greetings; in the evening, a separate reception was organized.

In general, given the frosty weather, there were "fewer people than there could be" at the event. The number of white and red symbols was quite sufficient, though. Against this background, the participation of the Austrian administration was unnoticeable, which is surprising, because Rutowski was the one who had not dismantled the Austrian eagle on the city hall during the Russian occupation, justifying himself with the "lack of money for works of this kind."

Subsequently, Tadeusz Rutowski’s visits became something like a mandatory programme for representatives of the Polish community. Moreover, a charity fund was founded in his honour, donations to which were regularly reported on in the press.

Andrey Sheptytsky's return to Lviv

The main event of 1917 in the life of Lviv’s Ukrainian community was the return of Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytsky. He was expected to come back since the February revolution in Russia, after which the metropolitan was released from exile. As early as April, the organizing committee began to coordinate the work of local committees along the Vienna-Lviv railway line. However, the metropolitan’s journey from Russia to Lviv was somewhat delayed and he arrived in the city on September 10.

After the train crossed the border of Galicia, it was greeted at railway stations by local priests, parishioners and schoolchildren. In Przemyśl, Andrey Sheptytsky was welcomed by the clergy and representatives of Ukrainian societies as well as by three members of the Lviv organizing committee, who had come to meet the metropolitan. Everything was done so that his return was in line with his status of "Prince of the Church and Citizen of Ukraine."

In early September, it became known that Archduke Wilhelm (Wilhelm Francis Joseph Karl von Habsburg-Lothringen) would take part in welcoming back Metropolitan Andrey to represent Emperor Charles. Wilhelm arrived in Lviv on the previous day, September 9, his arrival becoming a significant event on its own. The member of the Habsburg family, who was wearing a military uniform with the insignia of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, was met by the city commandant Kazimierz Grabowski, the police chief Józef Reinlender and the Ukrainian intelligentsia. After arriving, Wilhelm was taken to the George hotel.

The train with Andrey Sheptytsky arrived at the Lviv station at 1:45 p,m. on Monday, September 10. Archduke Wilhelm and hierarchs of three Catholic churches were waiting for him on the platform. Representatives of the authorities, the City Council, the Ukrainian and Jewish communities of Lviv delivered welcoming speeches in the station hall. Senior officers and officials of the regional autonomy were also present.

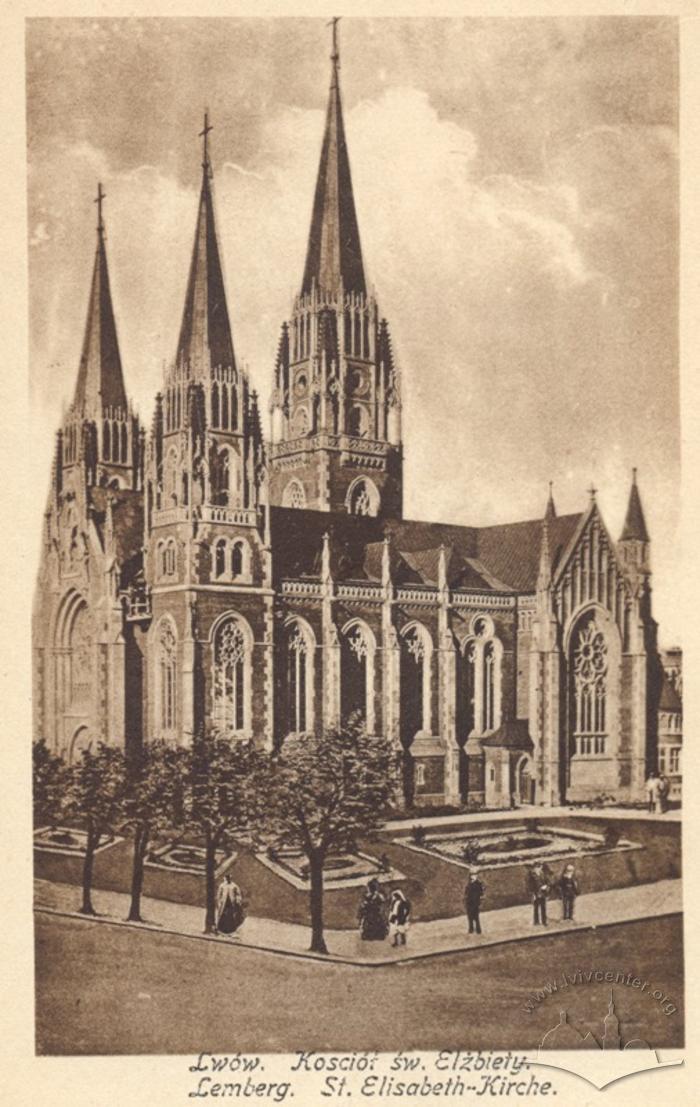

Girls strewed the path to the carriage arranged for the Metropolitan and the Archduke with flowers. People gathered along the way from the station to the church of St. Elizabeth, as well as on St. George's Square. The press noted that there were Sich Riflemen with an orchestra, Plast scouts, members of the Sokil society and non-military societies, schoolchildren (including those from Polish schools), pupils of orphanages, students, workers, peasants, railway workers, clergy, military. That is, it was not a typical purely Ukrainian mass event; the influence of the administrative resource, the Catholic Church, and the person of Andrey Sheptytsky himself was felt.

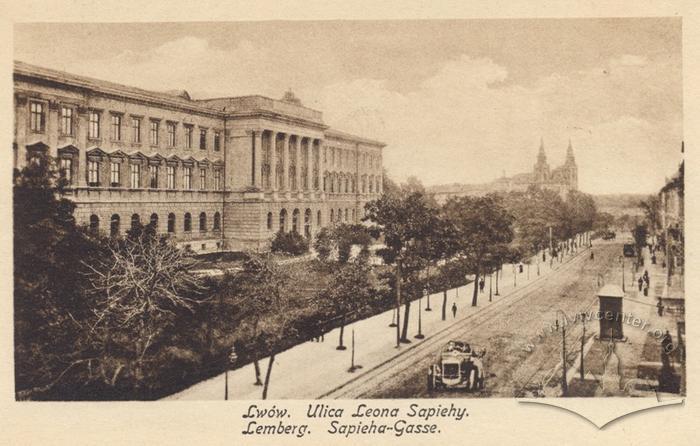

Having passed through ul. Dojazdowa, Gródecka, Sapiegi, and Sheptyckich to pl. Sv. Yura, the metropolitan, after a prayer and several speeches, blessed the crowd.

After that, a reception for approximately 150 people took place in the metropolitan chambers, during which Metropolitan Andrey "represented the Ukrainian community to Archduke Wilhelm." Monday's festivities ended with a program at the "Ukrainian Theater" (Lysenko Society).

On Tuesday, September 11, the metropolitan received visitors and then accompanied his guest Archduke Wilhelm to the station. In addition to the metropolitan, Governor General Karl Georg von Huyn, the city commandant, the chief of police, representatives of the intelligentsia, the clergy, and leaders of the USR Legion led by Hryhoriy Kossak came to see him off. Girls wearing Ukrainian national costumes presented Wilhelm with a bouquet of flowers with a blue and yellow ribbon, the crowd shouted "Glory!"

On Saturday, September 15, on the occasion of the metropolitan's return, a festive musical program was held at the Lysenko Society, and a cantata composed specially for this occasion was performed. After that, there were greetings from various societies, schoolchildren, teachers, and the like.

* * *

So, in 1917, mass events in Lviv were held mainly according to the "old calendar", known since the pre-war times. However, this calendar also contained some new dates, again treated by each political group as "their own." The same can be said about political agendas or visions of the future. What's more, the latter were "owned" by each group so much that it was practically impossible to reconcile the aspirations of the Ukrainians and Poles.

Welcoming "prominent citizens" demonstrated how well the Poles and Ukrainians learned the lessons of political confrontation during the times of autonomy — in particular, that one needs to behave like power in order to be power in the eyes of the people. Hence, there were many elements that Lviv residents should remember from the imperial visits: the civil guard as "their own army", a range of public figures for "representation" when greeting high-ranking guests, the maximum involvement of all layers of the "people" etc.