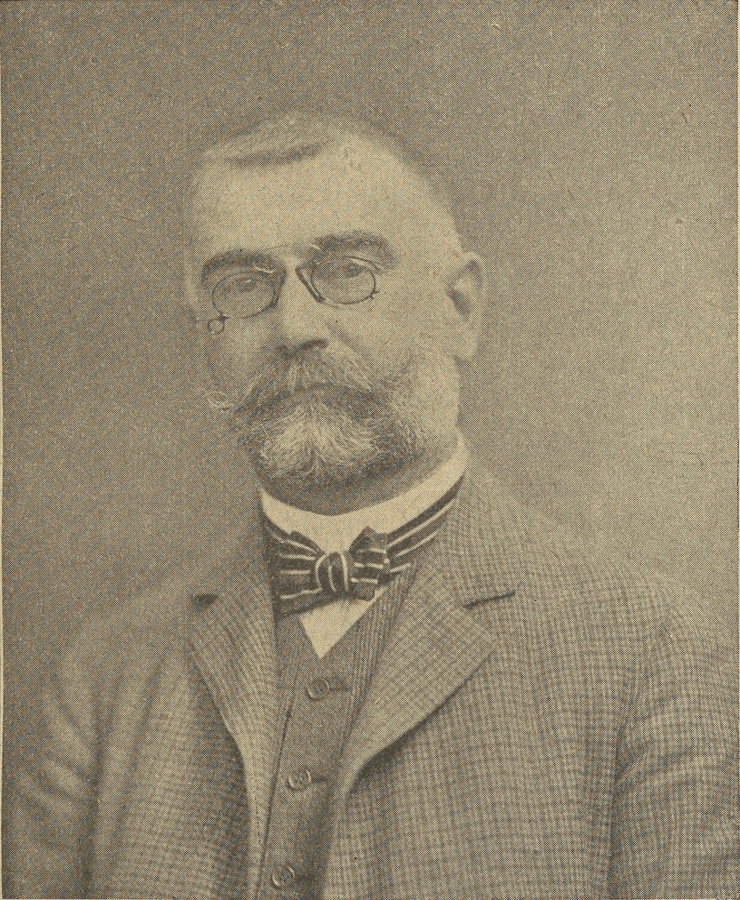

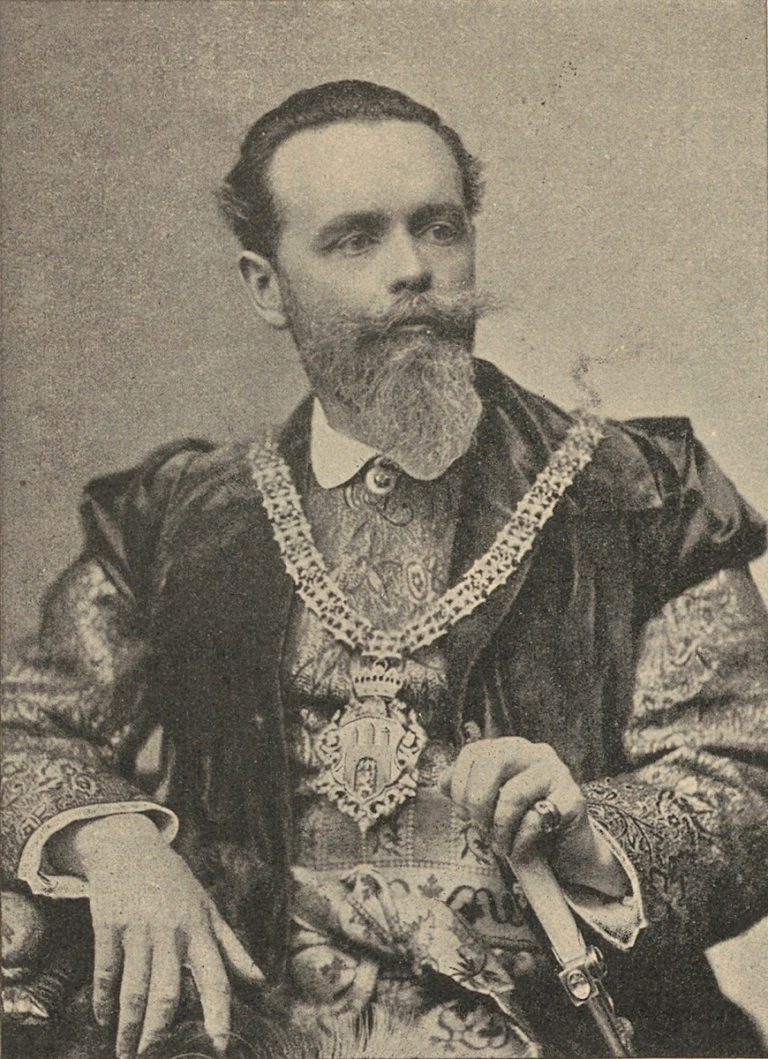

Franciszek Smolka was the one who started holding patriotic events and demonstrations in Lviv after the constitutional compromise of the 1860s. It is beginning from the celebration of the Union of Lublin anniversary in 1869 that we can talk about the mass politics of the times of Habsburg autonomy, when local elites got the right to hold such events instead of following instructions from Vienna.

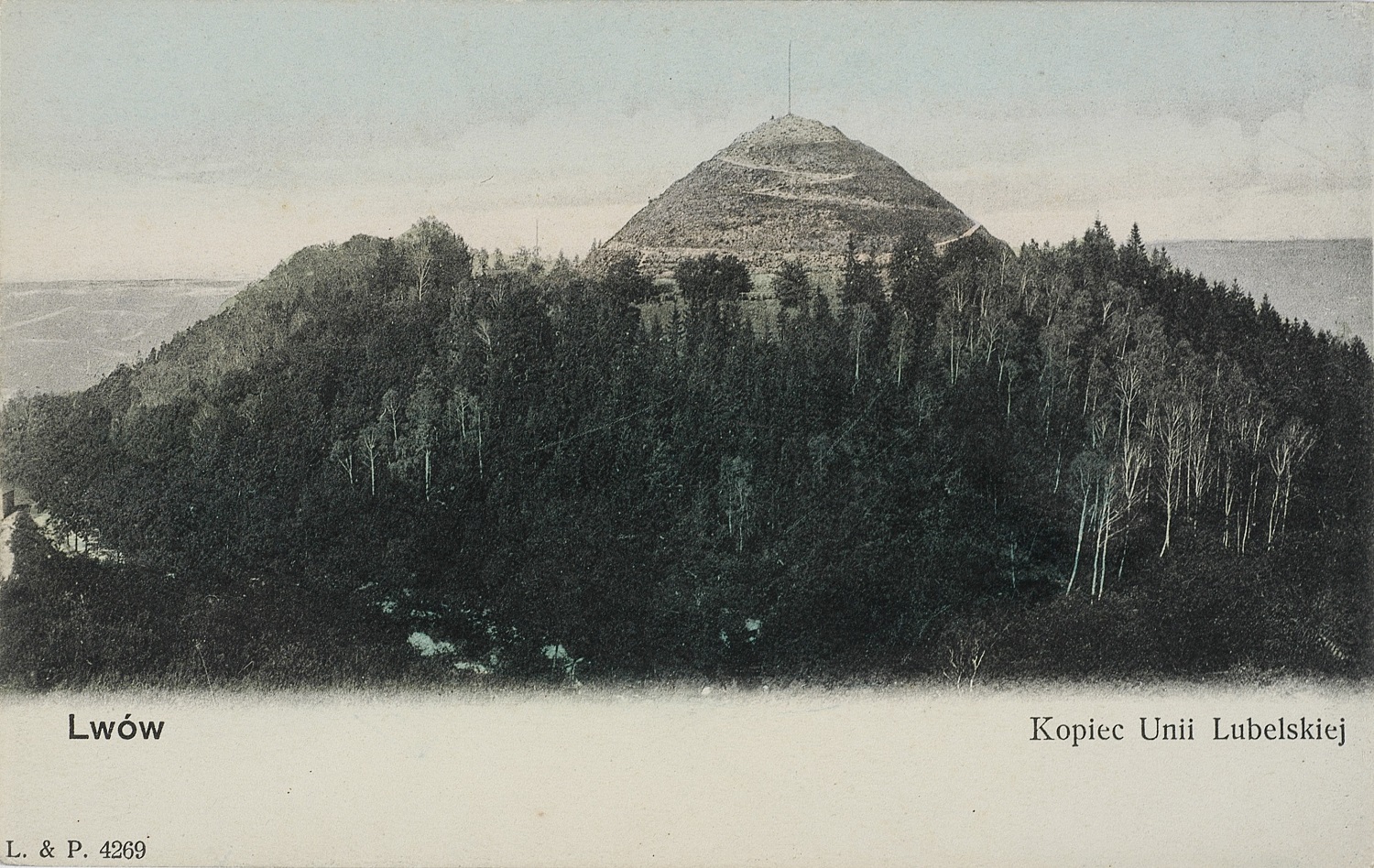

The mound, built on Smolka's initiative at the Vysoky Zamok (High Castle) Hill at that time, was a permanent testimony of his political activity, a kind of memorial erected during his lifetime. However, the immortalization of Franciszek Smolka in Lviv did not end there.

Funeral

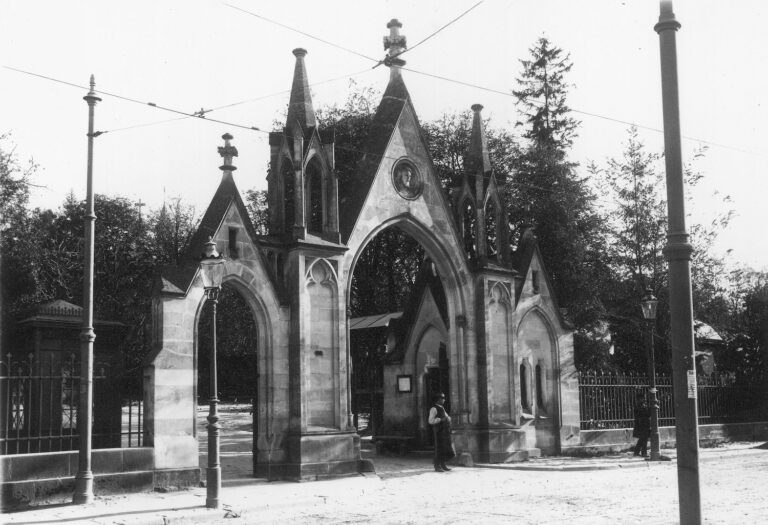

His funeral on December 7, 1899 was one of the many national events that funerals of figures of this magnitude usually turned into. The bells of Lviv churches were ringing, people "of all social classes from this part of Poland" gathered, the streets along which the procession was going had been cleared of snow, street lamps were covered with black cloths, mourning flags were hung on the houses. In order to emphasize that the deceased politician united the whole of Polish society, newspapers reported about "lots of wreaths carried by people wearing kontuszes, top hats and military uniforms."

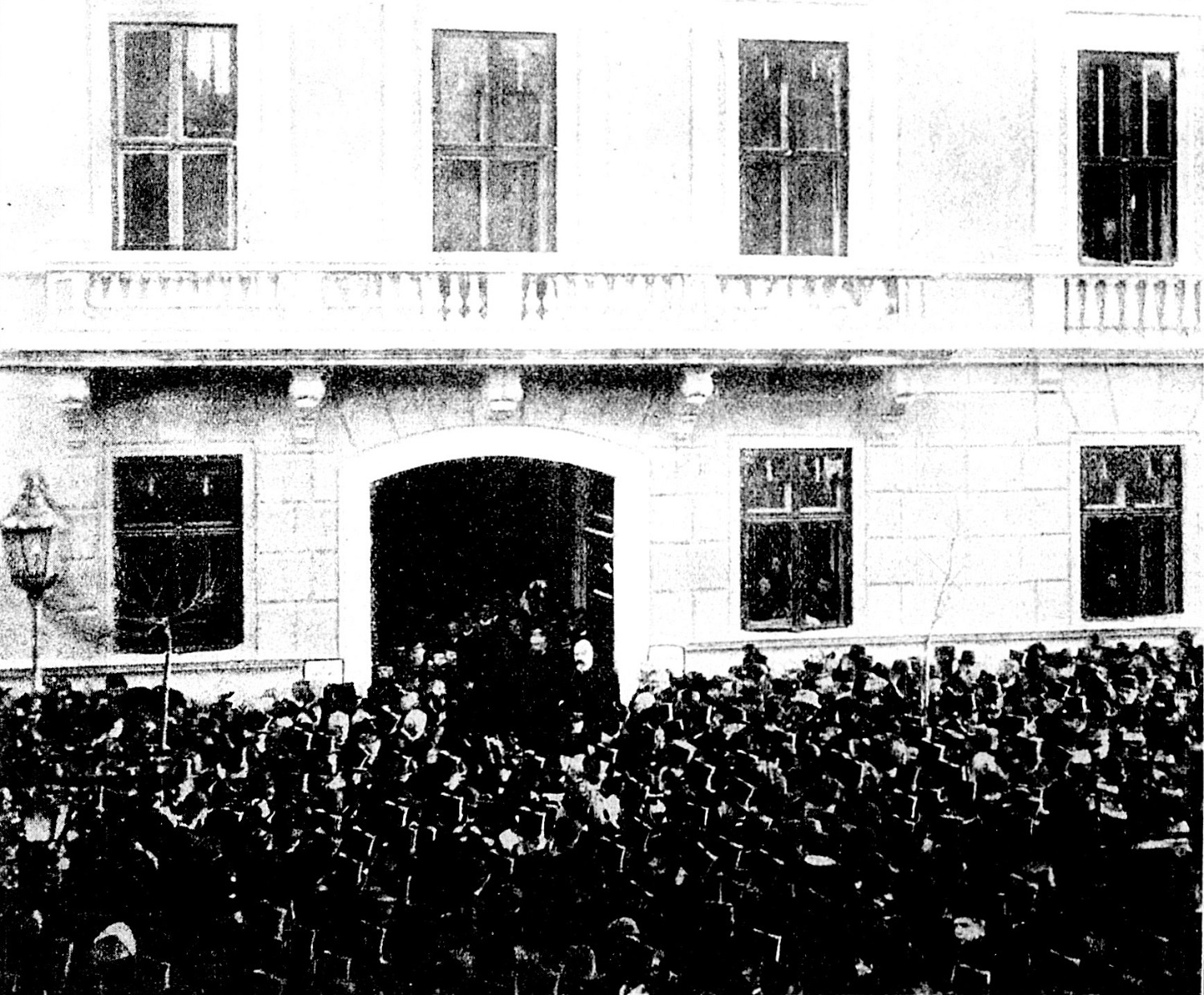

In front of the house where Franciszek Smolka lived, at Słowackiego Street 12, the civil guard was lined up in a square so that numerous delegations could pay their last respects to the deceased in an organized manner. Probably due to the fact that there were many officials and members of parliament, as well as considering the high status of Smolka himself, the cockades of the civil guard volunteers were made in the red and blue colours of the province and not in the Polish national white and red colours.

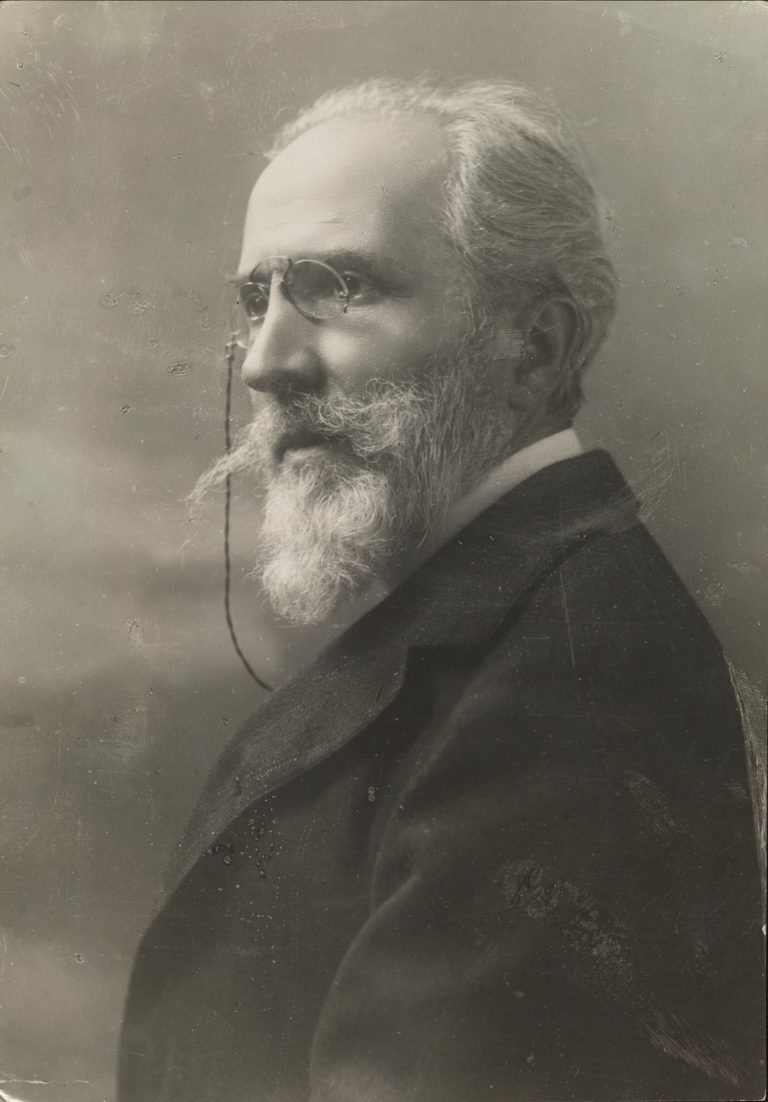

The Greek Catholic, Armenian and Roman Catholic hierarchs alternately held three religious services on Słowackiego Street; the provincial marshal Stanisław Badeni, dressed in a traditional nobleman's kontusz, delivered a speech. Then the march to the cemetery began to line up to the choir singing. Members of the Polish Sokół Association, pupils of orphanages, members of various associations, delegates from cities and municipalities of the province, members of the Austrian parliament took part in the march.

Parliamentarians and the president of Lviv, Godzimir Małachowski, spoke at the Lychakivsky cemetery over Smolka's grave.

100 years anniversary

In honour of Franciszek Smolka's 100th birthday, which fell on Saturday, November 5, 1910, the City Council organized a festive concert in the City Hall. The main "active person" there was the vice president of the city of Lviv, Tadeusz Rutowski, known for his patriotic position. In addition to the cultural programme and numerous speeches, funds for the future monument to Smolka were raised at the concert.

The monument opening

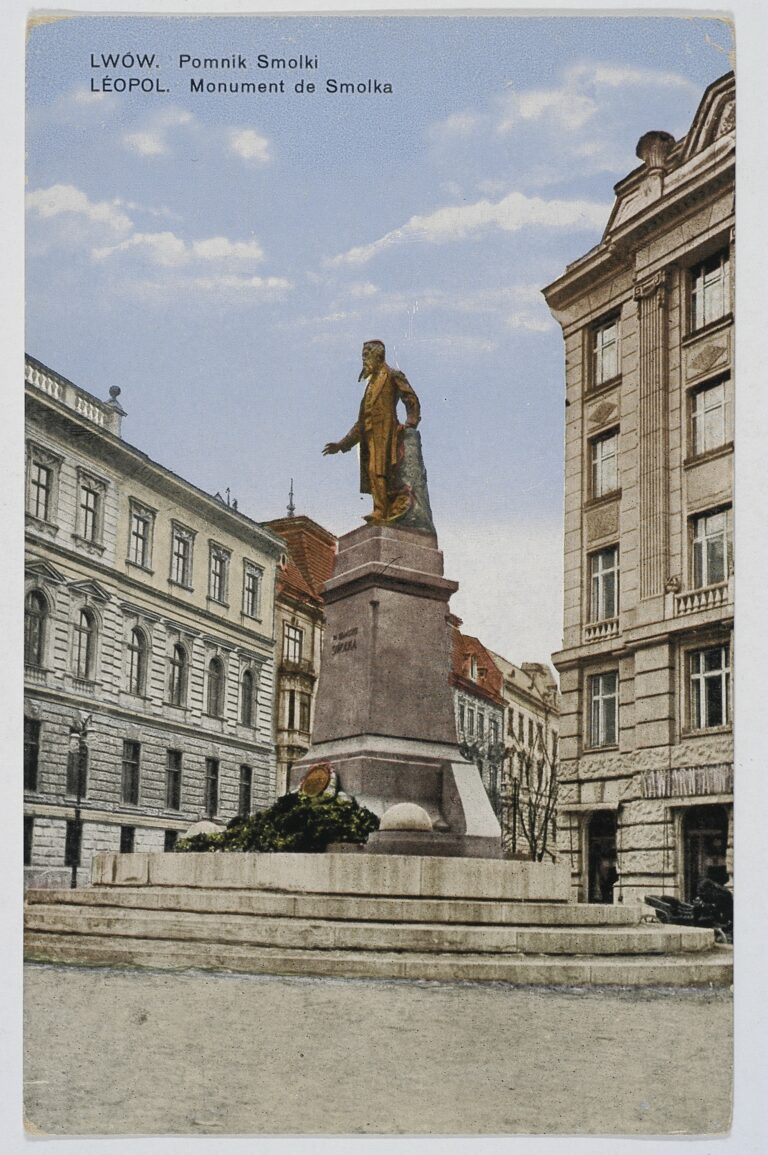

The square where Smolka used to live and where the erection of a monument to him was planned was named after the politician during his lifetime in 1885 (now it is Hryhorenka Square). The idea of the monument was announced in 1899, immediately after his death. A side effect of collecting funds and discussing the project was that the City Council paid attention to the mound of the Union of Lublin, which they consequently decided to put in order after all.

The monument was to be opened the day after the beginning of the Diet (Sejm) session, that is, at a moment when there were more regional politicians in the city than usual. On the day of the monument inauguration, on Monday, December 8, 1913, the police blocked all entrances to the square, only those invited were allowed to enter. Anyway, the balconies and windows of the houses were filled with spectators.

The opening ceremony began at 11:00. The family of Franciszek Smolka, ministers, the speaker and deputies of the Parliament and the House of Lords gathered near the monument. The presence of Czechs and Germans among them was particularly emphasized in the newspapers. There also were the governor, the marshal and deputies of the Galician Diet (Sejm), many of whom were dressed in traditional aristocratic kontuszes. Among the guests were representatives of Bukovina and the Hungarian part of the empire. And, of course, the Lviv elite: the Latin and Armenian archbishops, members of the City Council, representatives of the University, Polytechnic, Veterinary School, Agricultural Academy in Dubliany, senior officers of the regiments quartered in Lviv, as well as the leaders of various associations, organizations, and political parties.

An orchestra played, a choir sang, speeches were made from the podium and telegrams were read. A memorial plaque was built into the wall of the building that stood on the site of the one where Franciszek Smolka lived. In the evening, the guests attended a dinner at the governor's residence, followed by a reception in the City Hall.

Treatment

In the Polish patriotic press, eulogies dedicated to Smolka reached such a level that his role in the history of Austria-Hungary turned out to be almost a key one. Allegedly, he was the one who reformed the empire, and his reform project was even better than the one implemented in Vienna. Also, he served all the peoples of the empire, especially the Hungarians, who benefited the most from the constitutional changes. The Mound of the Union of Lublin was not just a monument on the occasion of a historical anniversary but a symbol of democracy, brotherhood, as well as the monument to Smolka himself.

Instead, government newspapers reacted to the event in a unique way. It was mentioned in two news reports: one was dedicated to the arrival of the Minister of Finance of the Empire in Lviv, while the other told about the visit of the Minister of Internal Affairs. It was only further on in the text that among the reasons of their arrival the opening of the monument was briefly mentioned.

The Ukrainians did not boycott the opening of the monument, it was attended by parliamentarians Kost Levytsky and Kyrylo Tryliovsky. However, the headline in the newspaper "Dilo" reading "An enemy of our nation" clearly hinted at a negative attitude towards both the monument and Smolka himself. The article claimed that the empire's federalization designed by Smolka envisaged absolute Polish power in the province and the assimilation of the Ukrainians. And now, a monument to such a person was being erected "in the old city of the Ruthenian princes." Nevertheless, the Dilo reported, one could not deny him political will and wisdom. He went beyond the borders of his own nation, hence representatives of many peoples of the empire were present at the monument inauguration. The Ukrainians, the article claimed, could only regret that there was no politician among them who would so successfully connect the problems of autonomy and all-imperial issues.

* * *

Consequently, on the images associated with Franciszek Smolka, which marked the public space in Lviv, one can also trace the evolution of the very idea of the Poles in the empire: from nostalgia for the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to an equal subject within Austria-Hungary, on a par with the Germans, Czechs or Hungarians.