Mass events held in Lviv in the first weeks of the war can be considered a continuation of the pre-war story — adjusted, however, to the new circumstances. The same solemn marches, rallies, speeches were held, though, only to demonstrate loyalty, imperial patriotism and support for the army. All other events were either cancelled or postponed indefinitely.

Nevertheless, nationalism found a way to show itself even in these conditions, the war raising hopes for the revival of Poland and Ukraine on the ruins of the Russian Empire.

* * *

On the first day of the war, July 28, 1914, while patriotic rallies were already held in Vienna, and the troops deployed in Krakow were pompously sent to the war, Lviv was still surprisingly calm. Trying to explain this, the government newspaper Gazeta Lwowska claimed that Lviv residents were optimistic about the future and did not succumb to provocations, as was the case in 1912 during the Balkan War, and, in general, life had become better. No one was nervous anymore, because everyone understood that there would be a war. Similar soothing materials appeared later in other newspapers. Thus, the democratic periodical "Kurjer Lwowski" stated that life in the city went on in its usual way, that the demonstrations showed the maturity and balance of the society and that one should not fall into a "political fever" taking away strength and energy.

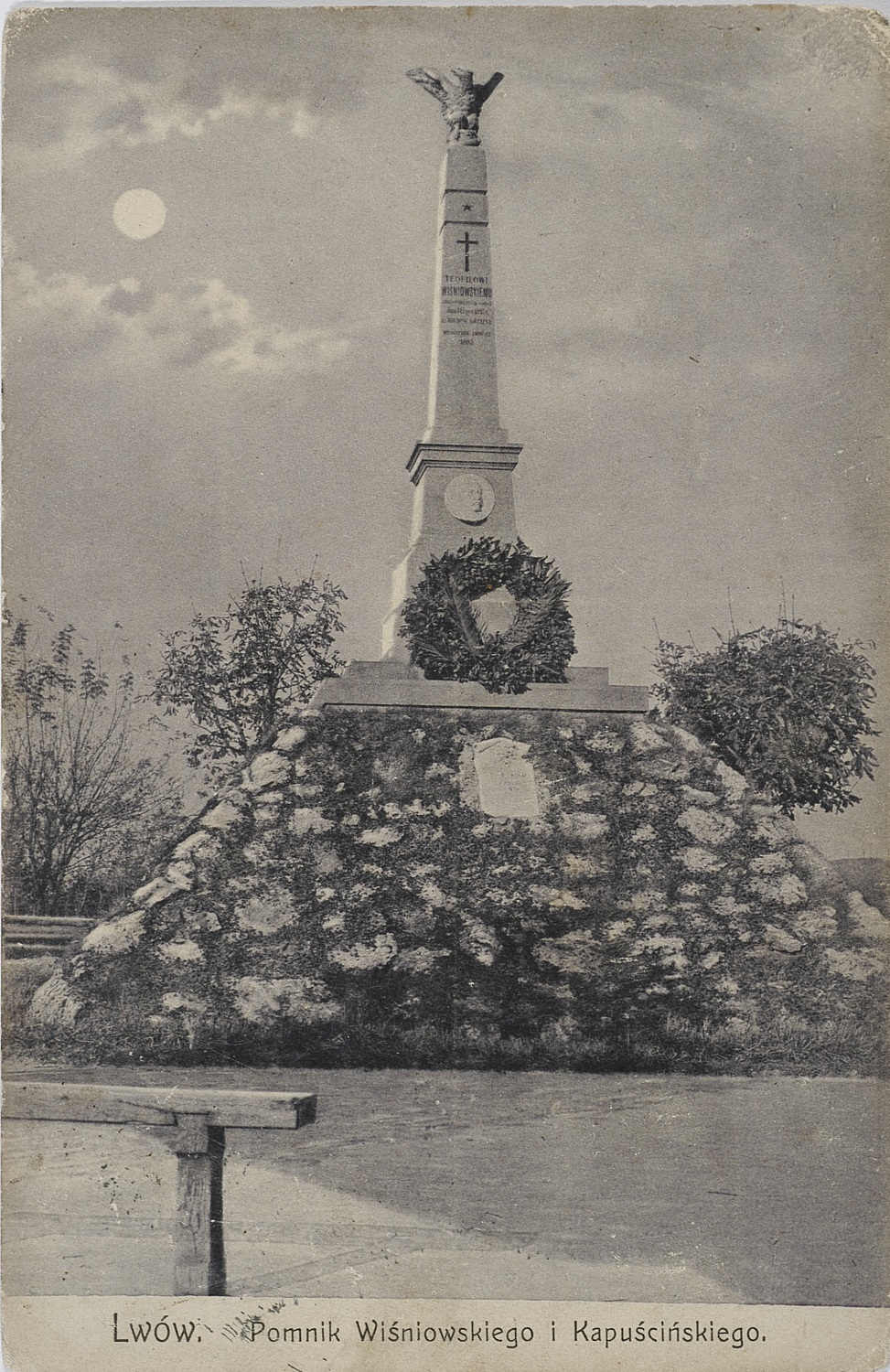

The press explained that it was due to this "calmness" and "moderation" that traditional Polish patriotic manifestations were cancelled in Lviv. For example, the commemoration of the rebels Wiśniowski and Kapuściński, executed by the Austrians, was limited to a mourning mass, and the march to the Mount of Executions was postponed "until more suitable times."

On the second day of the war, Wednesday, July 29, 1914, donations for the families of "Polish soldiers" began to be collected at an assembly of the City Council.

On the same day, the Ukrainians and Poles jointly held a rally in Vynnyky: there were two orchestras, two "civil guards" consisting of paramilitary organizations members, a joint performance of the national anthem, and even a thank you from the police commissioner for the participants' presence and order.

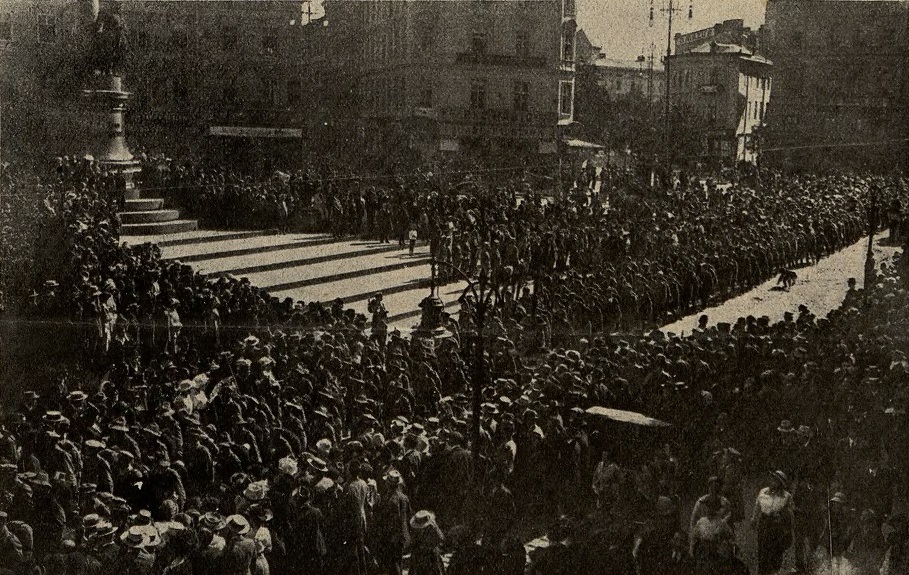

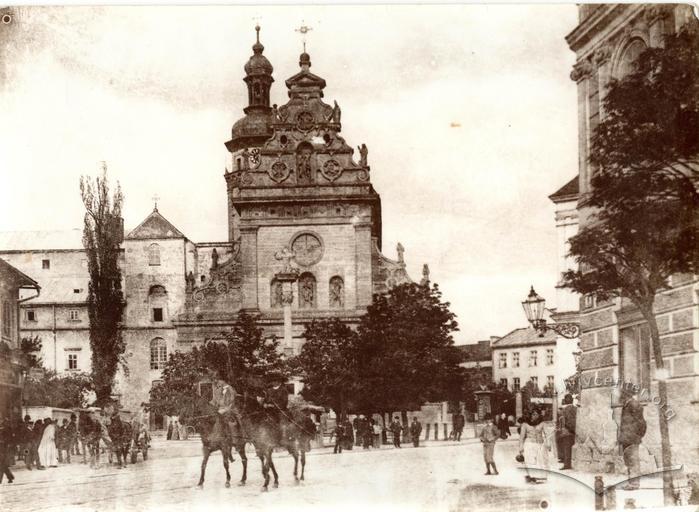

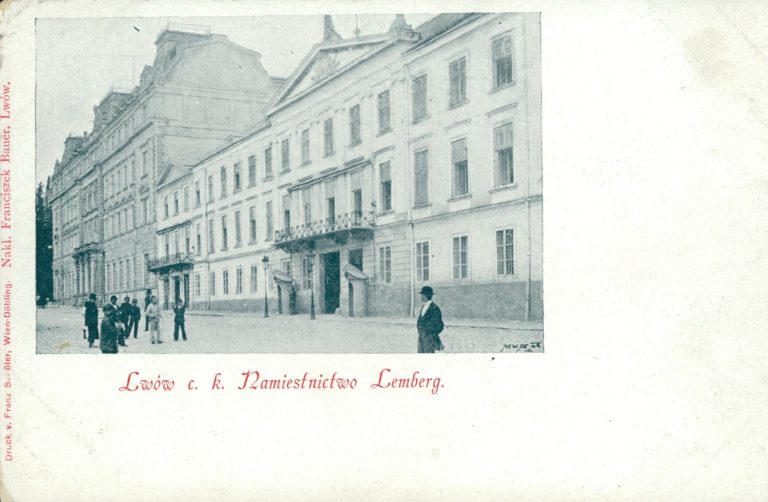

However, the main event on July 29 was a demonstration of several thousand people in the center of Lviv. At 7 p.m. demonstrators began to gather on pl. St. Spirit. Several thousand people (according to the government newspaper) marched with an orchestra to the monument to Mickiewicz and the Governor's palace. Here they sang the imperial anthem, the Radetzky March, folk songs, the Song of the Legions. Governor Witold Korytowski came out onto the balcony and greeted the demonstrators. Then the participants went along ul. Czarneckiego (now vul. Vynnychenka) to the military commandant's office. Here, too, the anthem was sung, the commandant and officers coming out onto the balcony to greet the demonstrators. Moreover, special attention was drawn by the press to the fact that officials and officers addressed the crowd in Polish. Then the programme was repeated near the military casino on ul. Fredra. Everywhere the emperor was praised and Serbia was shamed. Along the way the military were greeted and officers were carried in the arms of the people. The demonstrators' last point was the Galician Sejm (Diet), where they sang folk songs again and left around 10 p.m. However, orchestras played the national anthem, people sang and threatened Serbia in cafés and restaurants until late at night.

As can be seen, due to the beginning of the war, not only the goal and rhetoric of the participants of demonstrations in Lviv changed but also the geography. The participants of the rally visited not only, quite traditionally, governor's office or the monument to Mickiewicz but also the military commandant's office and the military casino.

On Thursday, July 30, the members of the Ukrainian "Sokil" society left their hall at ul. Grodecka 45 (where building 85 is now located) with standards, Austrian and Ukrainian flags, lanterns, an orchestra, as well as banners reading "Long live the Emperor", "Long live Austria", "Long live the army". They marched through the main streets to the governor's office, then to the commandant's office and to the military casino. Kost Levytskyi and Oleksandr Kolessa spoke to the participants. Then the demonstrators also went to the German consulate to express their solidarity with the Allies (the Poles would definitely not have done that, given the history of the consulate in Lviv), where they sang "God help" and "Ukraine is not dead yet." In the process, the Ukrainian sokoly ("falcons") were joined by passers-by, as it usually happened during events in support of the Austrian weapons.

On Friday, July 31, the president of the city of Lviv, Józef Neumann, convened an "extraordinary manifestation meeting" of the City Council in the large assembly room of the City Hall. The president, who, like many deputies, interrupted his summer vacation, talked a lot about "the war imposed on our good emperor." And since the emperor "gave us the opportunity for national development as an autonomy", he deserves the gratitude and support from the townspeople. After this meeting, which was essentially a rally in the city hall's assembly room, the councilors went to the governor. Witold Korytowski accepted them, and they pledged their loyalty to the empire through him. In actual fact, rituals of this kind, as well as greeting the demonstrators from the balcony, repeated the receptions by Francis Joseph of representatives of the province during his visits to Lviv. That is, it was something like showing loyalty to the emperor in the absence of the latter through his official representative, the governor.

In the evening of the same day, the orchestras of the regiments stationed in Lviv and the orchestra of military veterans marched through the streets of the city center. Due to the music and lights, a large crowd gathered; once again the people marched to the governor’s office, again singing the imperial anthem and other songs like "You, my Austria", and again the governor greeted them from the balcony on behalf of the emperor. Similar demonstrations took place simultaneously in front of the commandant's office and the cadet school.

The same thing happened on Saturday and Sunday, August 1-2. Bands of military units and veterans marched, accompanied by people with lanterns; posters with the image of the emperor and banners reading "Long live the army", "Out with Serbia", "Out with the king-killers" were hanging on the windows. The destinations of the rally did not change either: the anthem was sung near the governor's office, the commandant's office, and the military casino. The governor and the officers, respectively, thanked from the balconies.

On Saturday, August 1, cadet school last year students took the oath in the church of Mary Magdalene. On Sunday, August 2, a suspicious individual who had been behaving strangely near the city's water reservoir was detained; accordingly, rumours spread through the city that the water could be poisoned. Again, the city administration had to deny this.

On the night of August 4, it was even possible to observe an "ideal" picture, if, of course, it was not invented by journalists. When one of the infantry units was walking down ul. Piekarska, people began to open windows and applaude and shower the soldiers with flower petals.

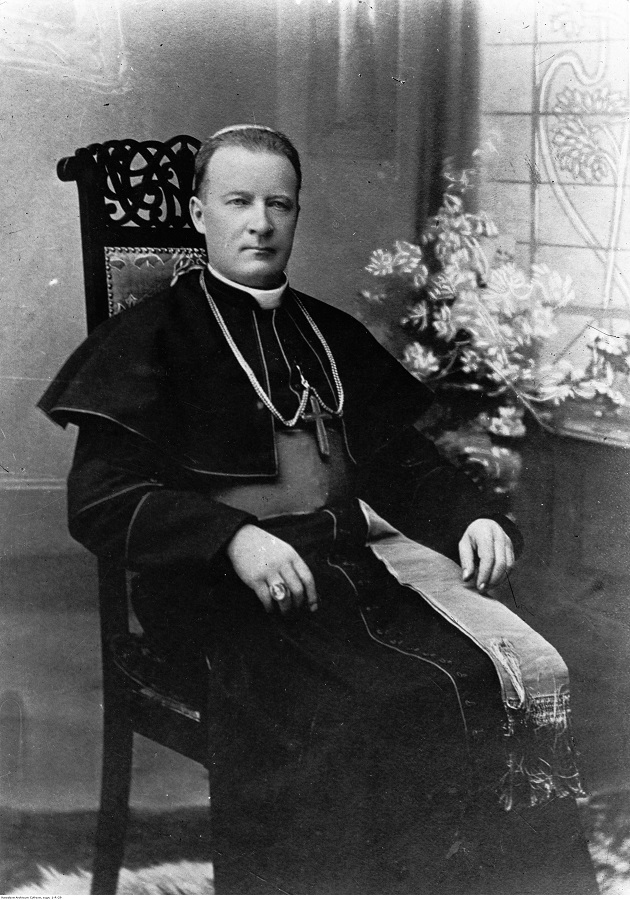

On August 5, on the 50th anniversary of the "execution of the five" in Warsaw (when the Russians hanged the participants of the January Uprising), a mourning service was held in the Latin Cathedral, conducted by bishop Władysław Bandurski, who was known for his patriotism. Considering the "round date" and the importance of the January Uprising for the early 20th-century Lviv residents, this celebration was more than modest.

On Saturday evening, August 8, another demonstration in support of the war took place. This time it was organized by Polish paramilitary organizations. The Sokoł society members and the general public gathered near the monument to Mickiewicz, where they sang the "Song of the Legions" and the "Warshawianka" (which may also indicate a turn to Polish patriotism from pure Austrian loyalty). Then the Hungarian officers, who stayed at the Francuski hotel, were greeted with applause. The latter, in their turn, sang the "Song of the Legions" in Hungarian from their windows. At the end, there was a traditional march through the streets to the governor's and the commandant's offices.

This, however, was only the "official" part described in a government newspaper. "Actually", from the Polish patriots' point of view, the demonstration was dedicated to the "victory of the Polish riflemen" near the town of Miechów in the environs of Krakow. After all, it was just on the previous day that the Austrian army units, staffed with the Poles, occupied this settlement, ousting the Russian army. It was described as "the first victory of Polish weapons on the way to independence", which happened, moreover, on the territory of the Kingdom of Poland. Accordingly, "as many people gathered as never before in the history of national demonstrations held in Lviv." The speakers talked about the "new map of Europe", the "liberation of the motherland with the help of Polish blood and Polish iron" and "free Poland" (Tadeusz Dwernicki), about the first spilled Polish blood, a revenge for past sufferings and readiness to fight; it was also said that the 20-million-strong Polish nation can form an army of 1 million (Michał Sokolnicki) and about the "struggle of peoples and nations" against the tsar's shackles" (Józef Hudec).

The joy caused by the successes of the Polish military units continued on Thursday, August 13, again at the monument to Adam Mickiewicz. Professor Bronisław Pawlewski said that "Polish riflemen" were occupying the territories of the Kingdom of Poland, where "Polish organizations and Polish government" were being formed. The participants congratulated the National Government created in Warsaw; then they went to the commandant's office (bypassing the governor's office), where they chanted slogans in honour of the "Austrian and Polish army".

It is important to remember that all these manifestations took place not only in the light of solemn and patriotic meetings of various societies, but also against the background of mass arrests of Russophiles, first aid courses, the search for workers instead of those who had been sent to the frontline, the "discovery" of Russian spies and campaigning among schoolchildren to take part in harvesting.

In spite of this patriotic exaltation, the situation was far from "victory." For example, a cheap vegetable market was organized on ul. Sykstuska due to the efforts of the Red Cross Women's Society. The profit from it was supposed to go to charity and the "national cause." Besides, due to low prices for foodstuffs, the "social market" had to restrain the growth of prices for products.

In the first weeks of the war, many newspaper reports described the enthusiasm with which soldiers were sent to the frontline or townspeople watching with interest enemy POWs passing through the streets of cities.

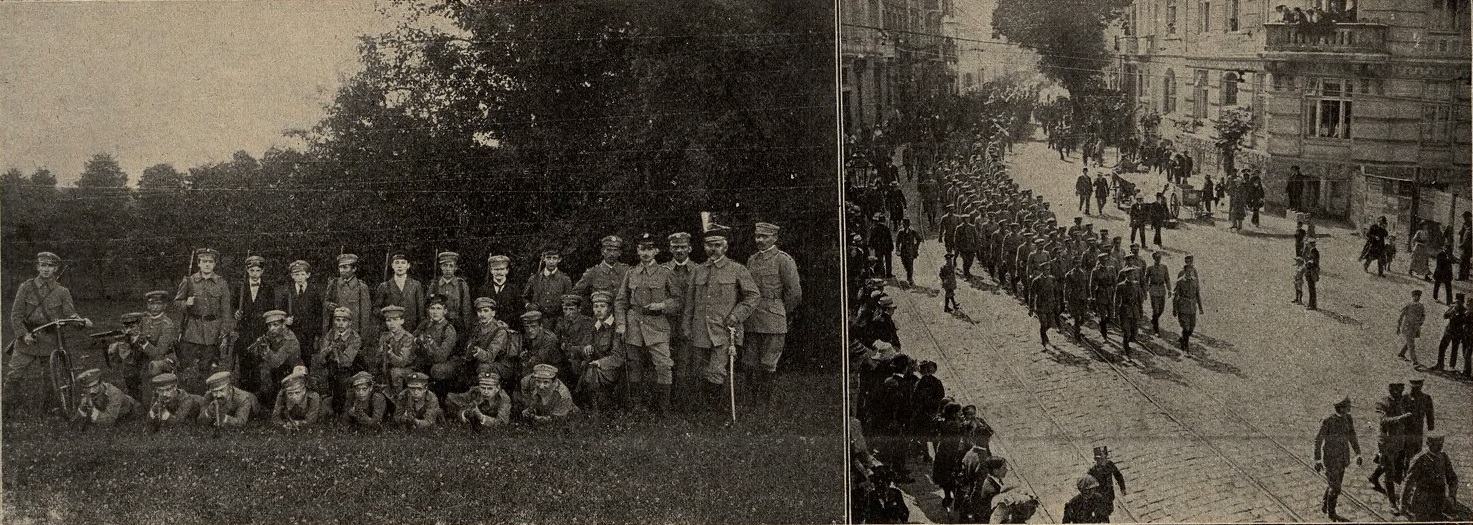

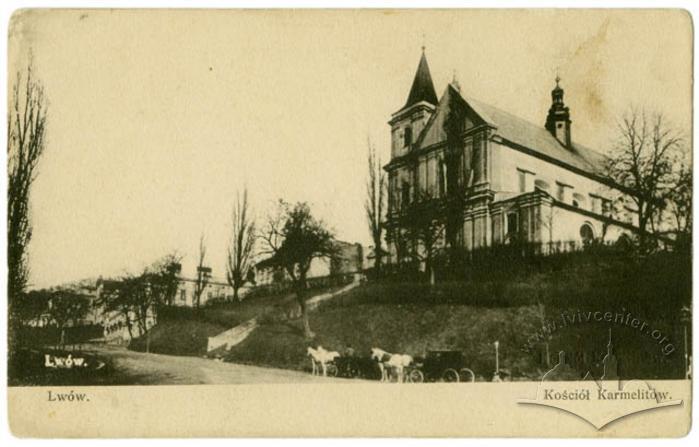

On Saturday, August 15, a solemn mass was held in the Carmelite church for the victory of the Austrian army (in the version of the government newspaper) or a service for the "Polish military" (from the patriotic press' point of view). There were lots of people in the church and around, many members of the Sokoł society in uniforms, the sermon contained appeals to help the army and sign up as a volunteer. After the service, those present sang Polish patriotic anthems "Z dymem pożarów", "Boże Ojcze", "Boże coś Polskę" and the "Song of the Legions", collected donations and went on a march through the city center. The march was led by members of the Polish society Sokoł in uniforms.

Notably, a mourning service for the fallen soldiers held on Tuesday, August 18, in the Bernardine church gathered significantly fewer people and attracted less press attention.

However, the reason may be the emperor's birthday, which, as usual, was celebrated at the state level on the same day, August 18.

On the previous evening, an orchestra of railwaymen marched through the streets of the city. Several thousand people with lanterns and torches once again went to the governor's and the commandant's offices with the usual program and then to the monument to Mickiewicz. There, in addition to the national anthem, they sang the "Song of the Legions", recited traditional slogans for the emperor, Austria and the army and left around 10 p.m.

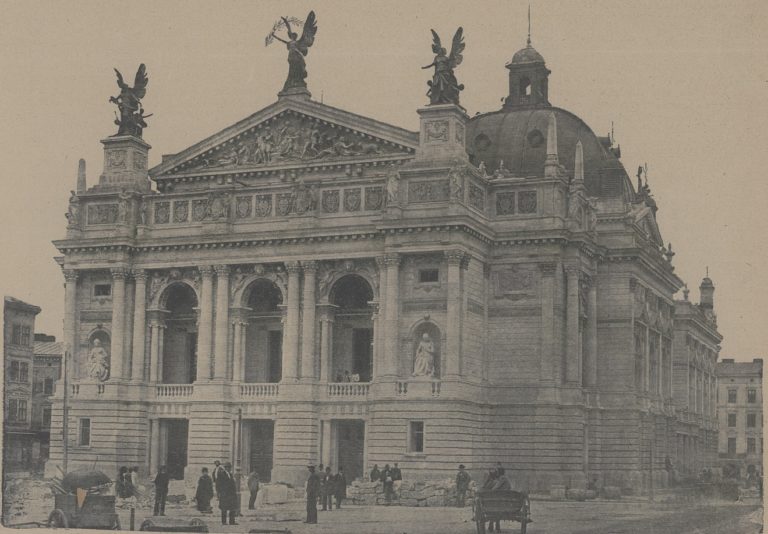

On August 18 massive decorations could be seen on the townhouses, though some windows in the city center had festive illumination on them as early as the previous evening. On all government and many private buildings there were flags of the monarchy and of the province as well as national (mostly Polish) flags, portraits and busts of the emperor could be seen in shop windows. On the City Theater building one could see the emperor's initials formed of small electric lamps. There was a large banner at the 7th gymnasium (now vul. Kovzhuna 8), rearranged into barracks.

At 9 a.m. solemn religious services began in all the churches of the city. Traditionally, most of the representatives of the authorities were present in the Latin Cathedral, less so in the Cathedral of St. George, smaller officials were evenly "delegated" to other churches and synagogues. As usual, representatives of Polish paramilitary organizations gathered in the Bernardine Monastery. After the services, governor Witold Korytowski received visitors: the same people who had attended the services, including Metropolitans Józef Bilczewski and Andrey Sheptytskyi. Meanwhile, a parade of "falcons, scouts and riflemen" was held near the monument to Adam Mickiewicz at which slogans were chanted not only for the emperor's health and the victory of Austrian arms but also for the "restoration of Poland."

This Polish activism eventually led to the fact that Ukrainian politicians complained to the governor about the City Council. The reason was that the Council allocated money for the "Polish legions", thereby underestimating the Ukrainians' contribution to the defence of Austrian interests on the battlefield. They also complained about the idea of forming a local militia, fearing that it would also turn out to be Polish.

Later on, there were fewer manifestations. Officially, it was due to the mourning for the death of the Pope, but objectively the reason must have been the influence of news from the frontline and the worsening of the material situation. If the government press is to be believed, one of the "entertainments" of Lviv residents at that time was viewing captured Russians, seeing-off the victorious Austrian troops to the frontline, welcoming the wounded, and hunting spies. Moreover, all this was done in the evenings, en masse, while during the day everyone conscientiously worked for the defence. For example, many curious people gathered on ul. Kazimierzowska on August 25, when three peasants accused of treason were executed.

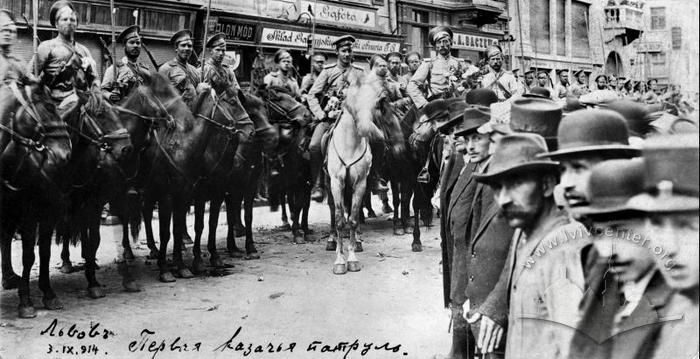

Rumours about the failures of the Austrian army were intensively denied until September 3, when the Russians entered the city.

* * *

Therefore, the mass events held in the first weeks of the war can be considered a continuation of the previous peaceful political process. Although it was allowed to speak exclusively in support of the victory of Austrian arms, calls to revive Poland or Ukraine, as well as to break the workers' shackles (again, in Russia) often slipped through during the demonstrations. The confrontation between the Poles and Ukrainians did not disappear, and even its standard course ("Polish grievances – Ukrainians' complaints") was not changed in essence.

Instead, the war brought "new" locations to the public space, such as the military casino, the commandant's office, and the cadet school.