The longer the war lasted, the stronger the conviction was that there would be no return to the pre-war situation. Both the Ukrainians and Poles promoted various options for the future system through the press: they sketched maps, "drew" borders, selected "historical" arguments, and calculated the percentages of the population in individual "lands." As it was aptly stated in the newspaper Dilo in August 1916, the war was not for land, cities and villages but for "the appearance of the national life of the Ukrainian, Polish and Russian peoples."

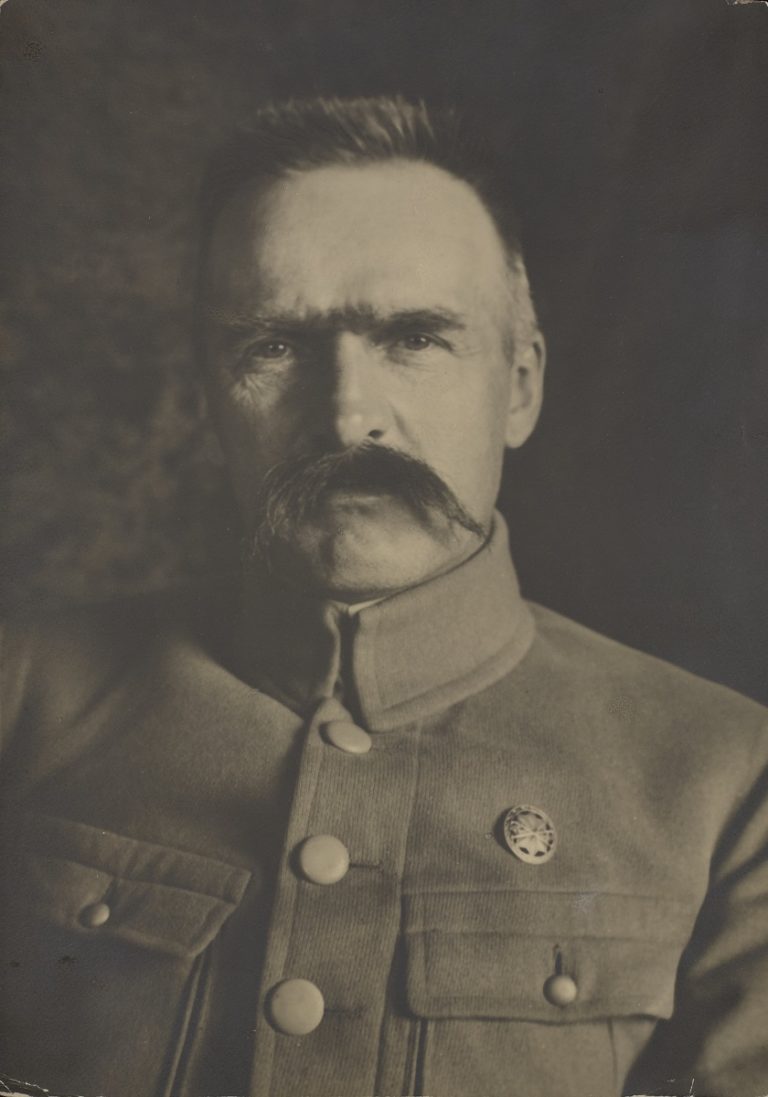

It turned out that the strongest argument in political debates was power, so the rhetoric of the Poles (reinforced by the presence of the Legions) and the rhetoric of the Ukrainians (reinforced by the actions of the Sich Riflemen) became increasingly sharp and uncompromising.

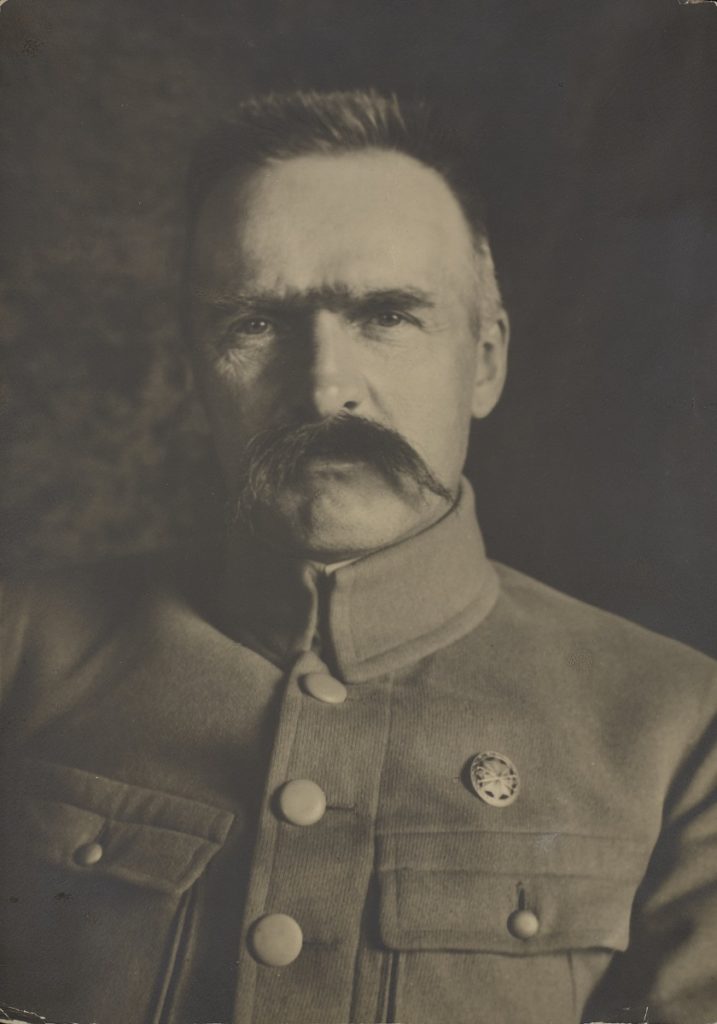

- Польські легіонери, по центру Юзеф Пілсудський / Polish legionnaires, in the center Józef Piłsudski

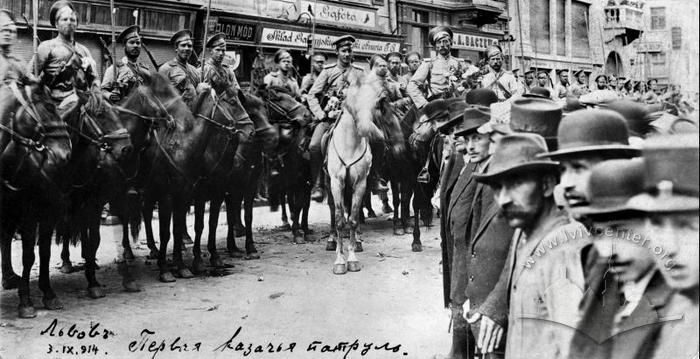

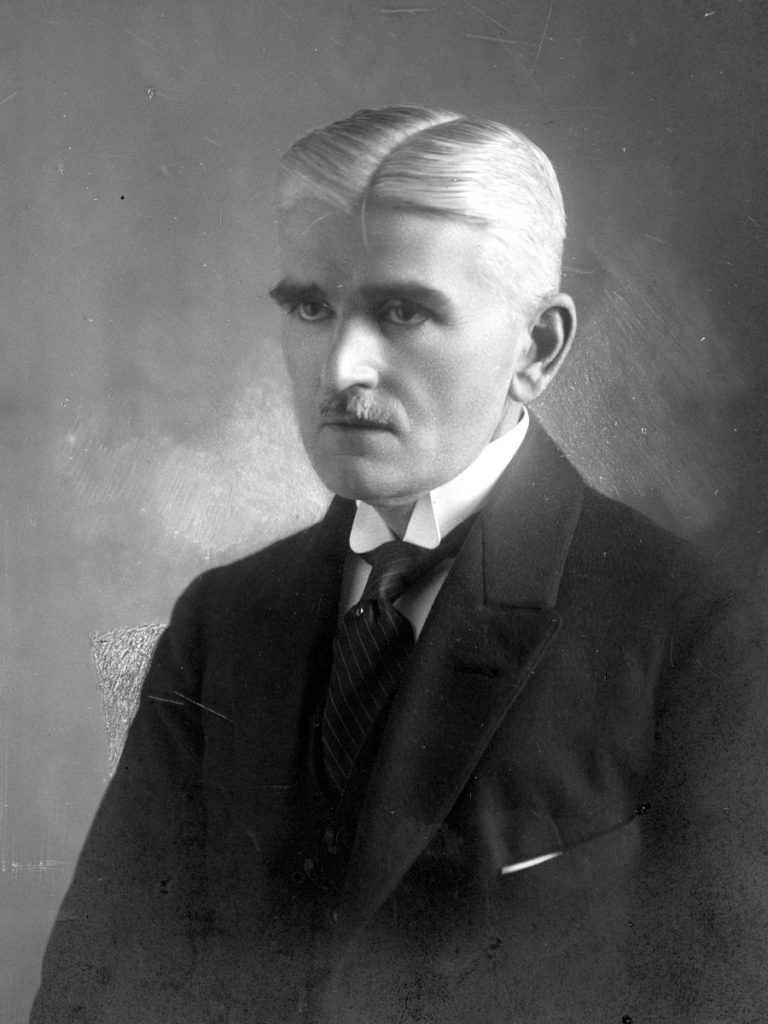

- Українські січові стрільці, по центру командант Антін Варивода / Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, center, commander Antin Varyvoda

Obviously, this state of affairs did not suit the Austrian authorities at all, as for them Galicia still remained a province of the empire and not a part of the future Poland or Ukraine. Vienna tried to limit national activism as much as possible in conditions where the monarchy depended on the favour of "its peoples." At the same time the imperial capital promoted its own ideological agenda, reserving the role of the chief arbiter for itself.

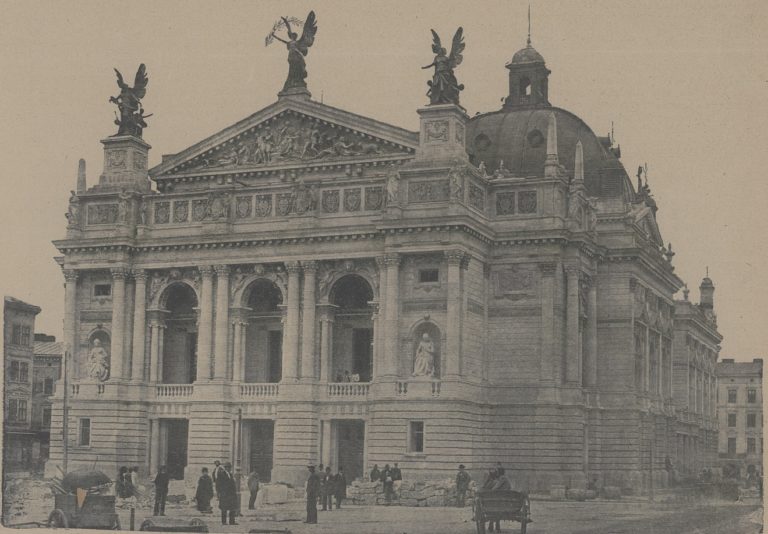

It is worth noting that the role of Lviv as a symbol and the capital of the region greatly diminished: the governor was mostly outside the city, the center of Polish life in Galicia moved to Krakow, everyone understood that the destiny of Poland’s future was being decided on the territory of the Kingdom. Besides, the patriotic events held for the military at the frontlines became more important.

All this took place against a backdrop of a rapid deterioration of the food situation and basic household troubles. Shortages of bread and tobacco, epidemics of smallpox and cholera, requisition of metal and lack of firewood for heating were common reports in the press of that time. It was only natural that the wealthiest Lviv residents were in no hurry to return to the city, while the poorest came first to receive the promised aid.

* * *

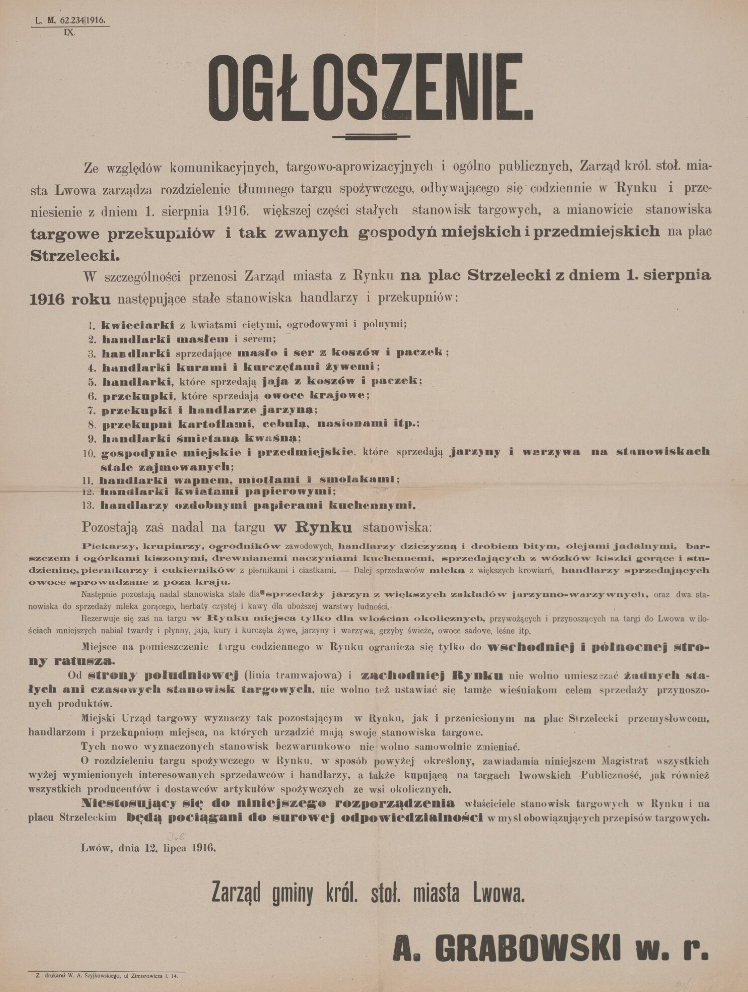

Announcement of the Lviv Mayor Grabowski on the transfer of bargainers from Rynok Square to Striletska Square

The economic life of Lviv in 1916 can be illustrated by the so-called "bargainers' strike" that happened in August. When, on August 1, 1916, the magistrate decided to transfer bargainers from pl. Rynok to pl. Strzelecki, leaving only sellers from the villages on pl. Rynok, part of the bargainers decided to protest. Since the trade on pl. Strzelecki was rather slow, the bargainers accompanied by a lawyer visited the city starosta Kazimierz Grabowski, but anyway they did not receive permission to return to pl. Rynok. In the meantime, vegetables were sold by soldiers and women from villages, and the "bargainers" were threatened with the elimination of places for trade. A week later, the magistrate won and about 150 stalls were put to work on pl. Strzelecki.

Another way to deal with high prices was to hunt profiteers. Both those who sold at an inflated price (that is, at a price higher than that set by the magistrate) and those who bought were punished with arrest for several days.

As a result, the peasants started to sell their products to wholesale buyers beyond the city limits, the queues in front of grocery stores were formed by the townspeople at night, and the police regularly conducted raids confiscating flour, coffee, sugar and other products from the profiteers.

It was against this background that the Ukrainians and Poles tried to manifest their presence as well as new ambitions in the public space of Lviv. Next to the old "national calendar", familiar since the time of autonomy, new dates and reasons related to the war appeared. At the same time, pressure from the central government forced national politicians to turn to the old scheme of using religious holidays for patriotic manifestations. The fallen soldiers of the "national army" were remembered in churches; on St. Andrew's Day, the Metropolitan Sheptytsky Foundation collected funds for orphans and widows of the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen; on Easter, Green Holidays or Corpus Christi, there were prayers for the victory of "our weapons", for the "future state", etc.

Meanwhile, the Austrian administration sought to make its own imperial agenda relevant. In honour of the frontline successes, even if these were achieved by the German army, houses in Lviv were decorated with imperial and national flags.

In early June, on the occasion of the end of the academic year, a new tradition was introduced in Lviv schools: commemoration and posthumous celebration of graduates who died in the war. Mentioning the soldiers' ethniciity or religion was also avoided, while their belonging to the Austrian army was emphasized.

Visits of honoured guests

Visits of dignitaries, organized by local politicians before the war, now became the prerogative of the military as well. On March 1, 1916, on the way from the frontline, a Turkish delegation arrived in Lviv. The guests stayed at the George Hotel, had lunch with Austrian and German officers, toured the city with them, visited the Loziński Palace (now the Lviv National Art Gallery), the so-called Airplane Park, the Vysokyi Zamok (High Castle), and the City Theater. Before the war, it was impossible to imagine a situation where the city of Lviv would be presented by someone except Lviv residents.

On April 12, Archduke Francis Salvator arrived in Lviv to inspect the work of the Red Cross and the system of evacuating the wounded by railway; he also visited a school for the disabled on ul. Kurkowa (now Lysenka). Again, there was no hint of flirting with the national ambitions of the local elite.

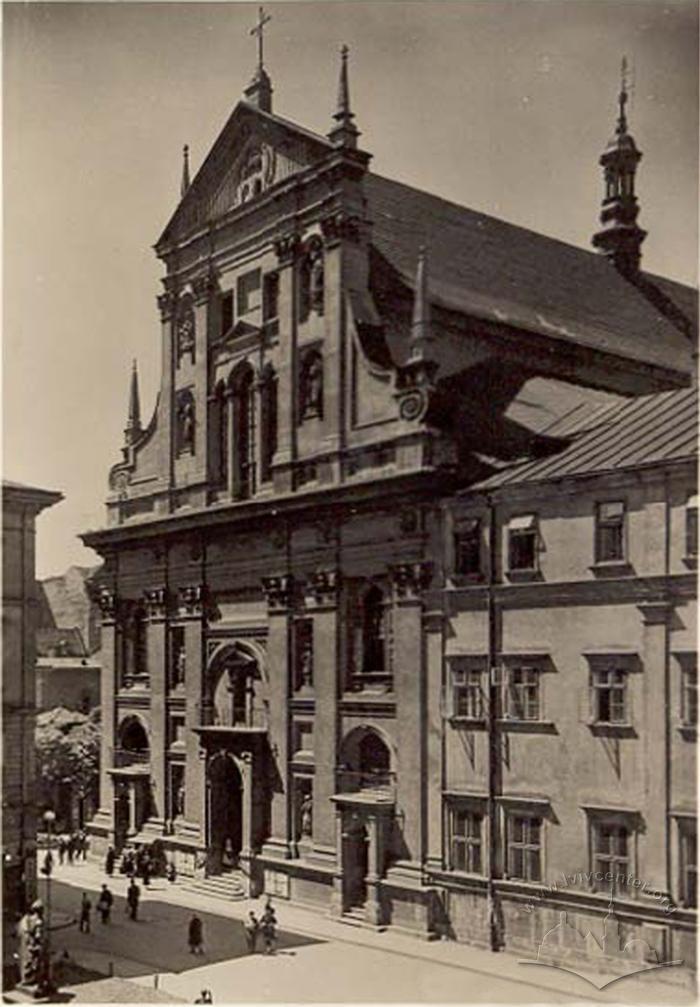

The visit of King Ludwig III of Bavaria took place on November 4, 1916, in a similar manner: in the company of German and Austrian officers, the guest visited the German consulate, the Vysokyi Zamok and the German hospital (in the premises of the governor's office) and had lunch in the chief commandant's office (in the Sejm building). On this occasion, the houses of Lviv were decorated with the flags of Austria-Hungary, Bavaria and Prussia, as well as provincial ones. On the following day, November 5, when it became known that a "free Poland" was declared by the Austrian and German command in the occupied lands of the Russian Empire, the king attended mass in the Jesuit church, visited the Kilińskiego Park and the post-exhibition square and viewed the panorama of Racławice. Before leaving the station, the king congratulated the "restored Poland" on its independence.

King of Bavaria Louis III in Lviv. According to the signature in the newspaper, it is under the German consulate. The photo shows the villa at 5 Franciskanska Street at the time.

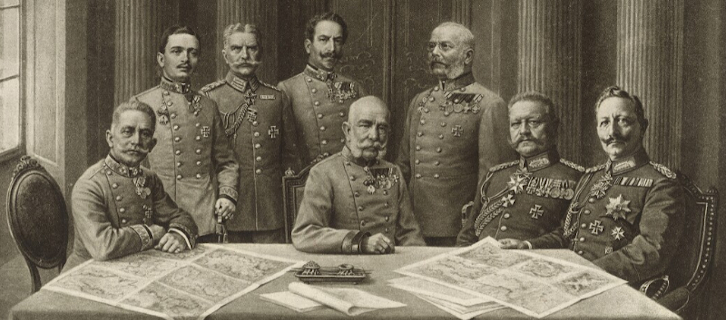

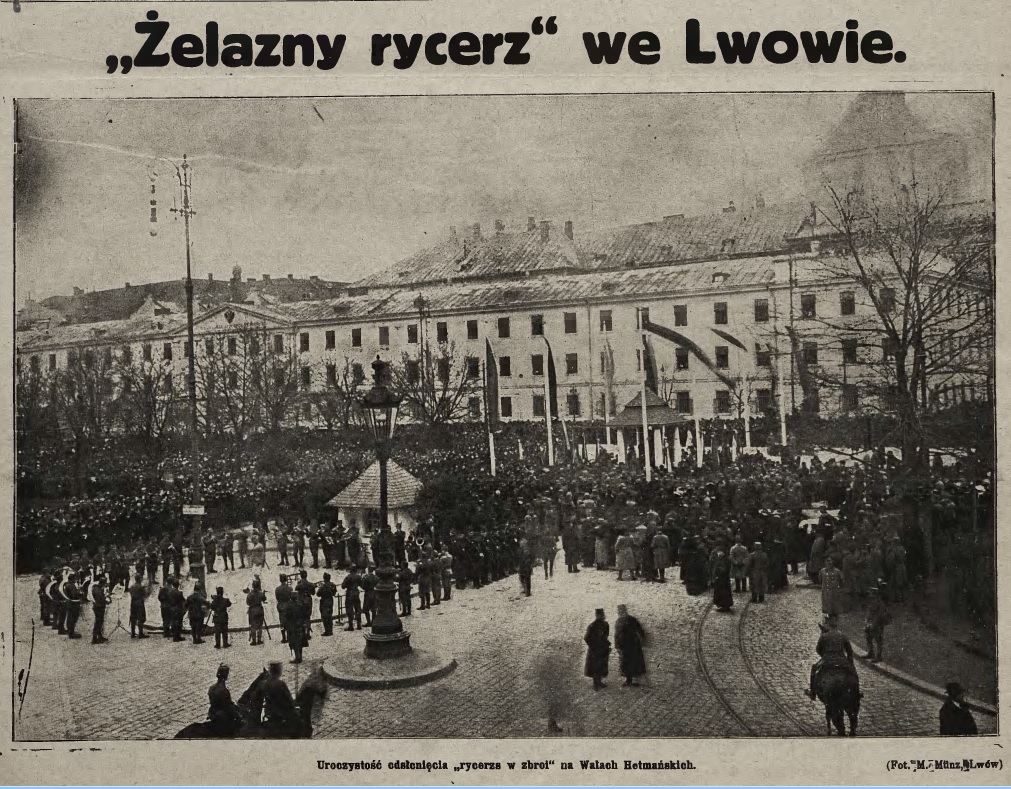

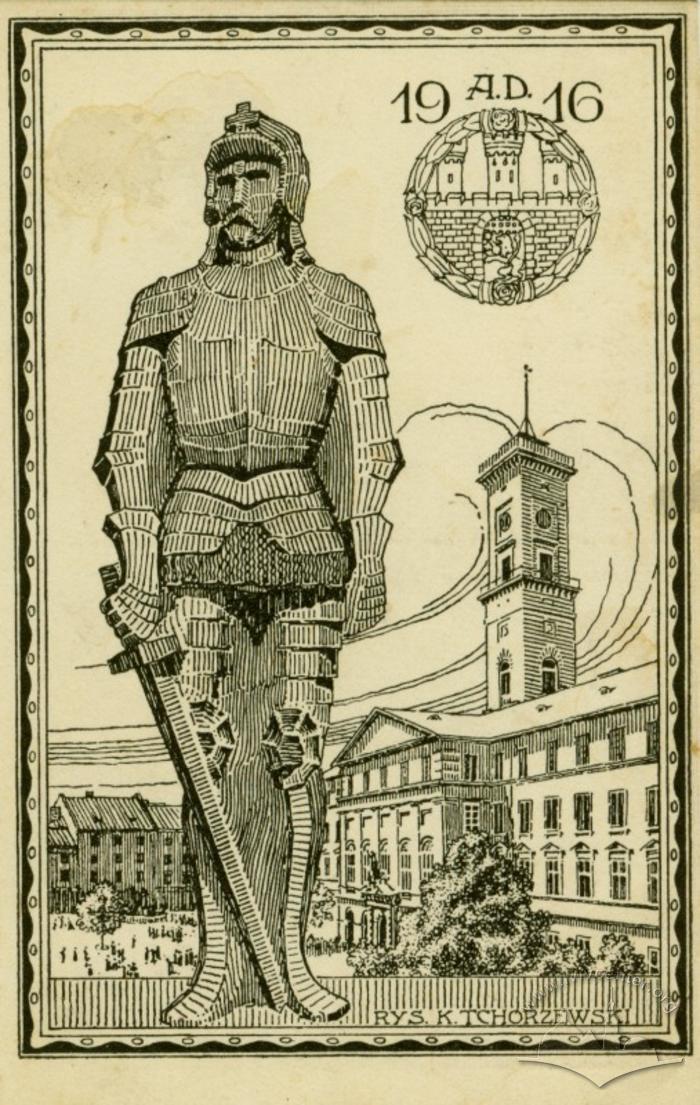

Inauguration of the Iron Knight statue

An important patriotic event organized by the central government was the unveiling of the Iron Knight statue on April 2, 1916. Inspired by the example of Vienna and officially at the initiative of Emperor Francis Joseph, a wooden sculpture was installed, which, due to nails hammered in it, was supposed to become an iron one. Each nail was to be hammered after a charitable donation for the army, soldiers' widows, orphans or military invalids.

Since the initiative had come from the emperor, the main role in the sculpture inauguration was to be played by the governor. However, he fell ill, so the Iron Knight was unveiled on behalf of Francis Joseph by the military commandant of the city of Lviv, Major General Franz Riml.

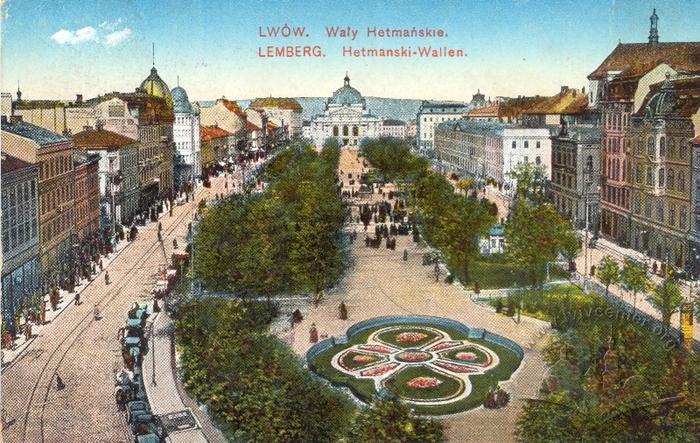

The day before, on Saturday, April 1, when the sculpture, covered with a white cloth, and the pavilion for it had already been mounted on ul. Wały Hetmańskie, a special program, was organized in the City Theater. The opening took place on Sunday, April 2. At that time, houses were decorated, illuminations were prepared, and airplanes were circling over the city. On the day of the opening, crowds filled ul. Hetmańska, pl. St. Spirit, ul. Karola Ludwika, and ul. Wały Hetmańskie. People were on the balconies, looked from the windows and even settled on the roofs of the buildings. The military organized a corridor through which the invited persons approached the statue, decorated with green branches and flags. A separate "walk" was organized for Major General Riml, who represented the monarch. He was met by the members of the committee for installation of the statue, including the starosta Kazimierz Grabowski, the rector of the University Kazimierz Twardowski, the chief of the Lviv police Józef Reinlender and others. At 11 p.m., Franz Riml arrived by car, the military saluted, the orchestra played "God, help." Church dignitaries, professors, members of the Lviv city council, consuls of foreign countries, directors of institutions, representatives of authorities and numerous societies were already waiting by the statue.

In the speeches given by dignitaries, it was emphasized that this initiative was the embodiment of the emperor's concern for the military and their families, that it did not depend on ethnicity or religion, and that what was important now was the loyalty of the city's citizens to the monarchy. At the moment of the statue unveiling, the orchestra played the imperial anthem, and the first nail was hammered by Major General Riml on behalf of the emperor. Next, representatives of the government, churches, consulates, societies, and organizations hammered in their nails, the process lasting for several hours. Then a military parade was held, which was followed by a parade of schoolchildren.

At 5 p.m., a reception was held in the city hall, where about 400 participants were invited.

Using the example of this manifestation, one can imagine how the Ukrainians saw the picture of relations in the triangle "Poles - Ukrainians - Empire". The newspaper Dilo quoted Austrian officials as saying that "Austria is a nation of nations where no nation can be considered superior." The periodical noted that printed products (announcements and invitations) were prepared in different languages, including Ukrainian. In general, the report stated, the inauguration corresponded to "the national composition of the province and its capital, located in the Ukrainian part of the province", because the nails were also driven in on behalf of Ukrainian organizations.

In the future, hammering nails and charitable donations became part of the "mandatory programme" for various societies and organizations; for example, in October, about 1,300 students from schools in the vicinity of Lviv were brought to the city to drive nails in the Iron Knight.

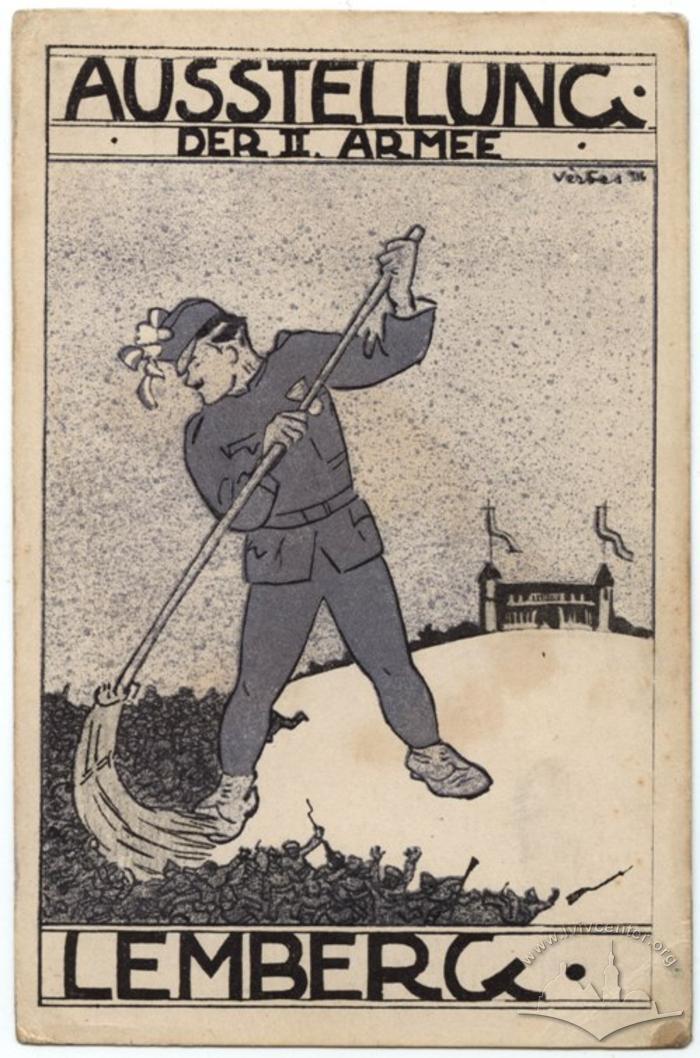

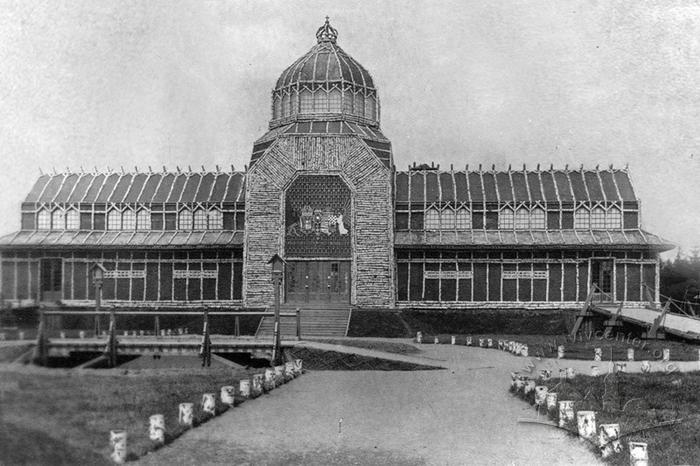

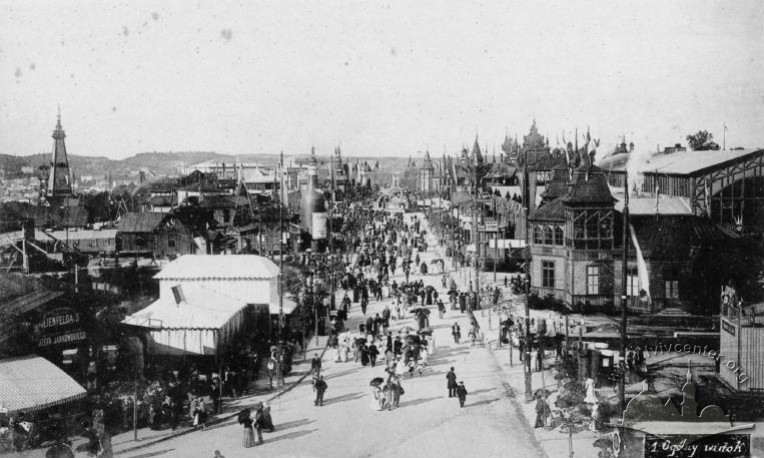

Anniversary of the liberation of Lviv from Russian occupation

Another imperial event was planned for June 21-22, 1916: the first anniversary of the liberation of Lviv from Russian occupation. On these days, there were plans to open a military exhibition organized by the City Archives and the command of the 2nd Army, solemn thanksgiving services and a performance in the theater. In addition, June 22 was the feast of Corpus Christi, which was an important date in the calendar of Lviv, associated with the Rifle Association and the "election" of the "chicken king." For the exhibition, new pavilions were built on the post-exhibition square; military trophies, exhibits telling about life under the occupation, etc. were collected. Residents were also asked to send their own exhibits.

However, as of June 21, heavy fighting continued at the frontline, so the event was limited to a modest Corpus Christi celebration. Official reports persuading that there was no reason to get evacuated from Lviv — reports of this kind had preceded the occupation of 1914 — also hardly added confidence. However, the anniversary of the liberation of Lviv was celebrated in Vienna, in particular by the Ukrainians, who even organized a "Ukrainian demonstration" there.

On the anniversary of the Austrian troops return to Lviv, the Polish press noted that constitutional rights, including those national, had returned with the Austrians, as well as a sense of personal security. At the same time, however, a new Poland would be born out of the current cataclysms. It was a wake-up call for the Austrians and Ukrainians, but the Polish legions were fighting against Russia, so the censors had to connive even at things of this kind.

After all, the exhibition was opened for viewing in the last days of July 1916; as early as August 6 there were reports that "the recently opened exhibition would soon move to Budapest." Nevertheless, the exhibition was visited by a Bavarian prince, the younger brother of King Leopold III, Field Marshal of the German Army Leopold von Wittelsbach in early September. The 2nd Army took away its exhibits, while the part organized by the City Archives remained.

The exhibition consisted of several buildings erected by Russian prisoners of war: barracks for soldiers and officers, a field church, utility premises, a Red Cross hospital, a frontline post office. A trench was dug around them, and trophy Russian weapons and equipment were placed.

The war exhibition, as well as the Iron Knight statue, were not Lviv inventions; a model for these initiatives was Vienna, where a similar exhibition opened on July 1, 1916. While the Ukrainians did not have any complaints about the Iron Knight, there were some comments regarding the exhibition, namely the part from the City Archive. The Ukrainian newspaper reported that the Lviv archivists did not demonstrate a single exhibit in the Ukrainian language.

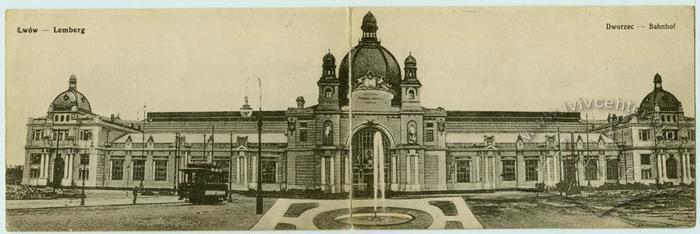

Lviv was also visited by the then commander of the Eastern Front, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg. At 7:20 p.m. on August 3, 1916, he was met at the station by all the senior officers (led by Eduard Böhm-Ermolli), accompanied by a military band and a guard of honour. The orchestra played the German anthem, after which the field marshal was taken by a car to the Sejm building, where the military commandant's office was located. In addition to the commandant's office, where a small reception was arranged, Hindenburg visited the German consul. At 1 p.m., the field marshal left Lviv.

Emperor Francis Joseph's birthday

On August 17-18, 1916, the celebration of the emperor's birthday was under way. This was another example of how imperial celebrations emphasized the army and excluded flirting with national projects. On the evening of August 17, a military band and soldiers of "both armies" (Austro-Hungarian and German) marched with torches through the streets of the city center to the commandant's office on pl. Bernardyński, where the imperial anthem was performed. The city hall and main buildings were decorated and illuminated.

The day of August 18 began with an army wake-up signal, followed by traditional religious services, a field mass and a parade for the garrison at the Citadel, dinners for officers, reception at commandant Franz Riml's office, a performance in the theater. From 8 a.m., several airplanes were flying over the city, launching light and smoke flares. Trams were decorated with flags and greenery.

Ukrainian and Polish manifestations

In spite of this policy adopted by the Austrian authorities, the Ukrainians and Poles anyway had more opportunities for demonstrations than during the Russian occupation. For example, on January 19, 1916, a guard of honour from the 41st infantry regiment was involved in celebration of Epiphany by the Greek Catholics. The procession from pl. Rynok, where the water was consecrated, to the Church of the Transfiguration took place to the sound of military volleys, officers, representatives of the authorities and higher schools taking part in the festivities. Compared to the Epiphany 1915 under the Russian occupation, it was a truly massive celebration. Although in 1915 the Greek Catholics, at the insistence of the city president Tadeusz Rutowski, were allowed to consecrate water on pl. Rynok, the main events were held by the Orthodox bishop Evlogi on pl. Franciszkański (next to the Orthodox church) for Russian soldiers, the police and Russophile groups. The peculiarity of the 1916 Epiphany was that the majority among the faithful present were women and children, while men had been largely sent to the frontline.

During 1916, the Ukrainians also organized evenings on the occasion of the "holiday of freedom." Before the war, it referred to the serfdom abolition; that year, however, it was combined with the commemoration of "liberation from the Russian yoke."

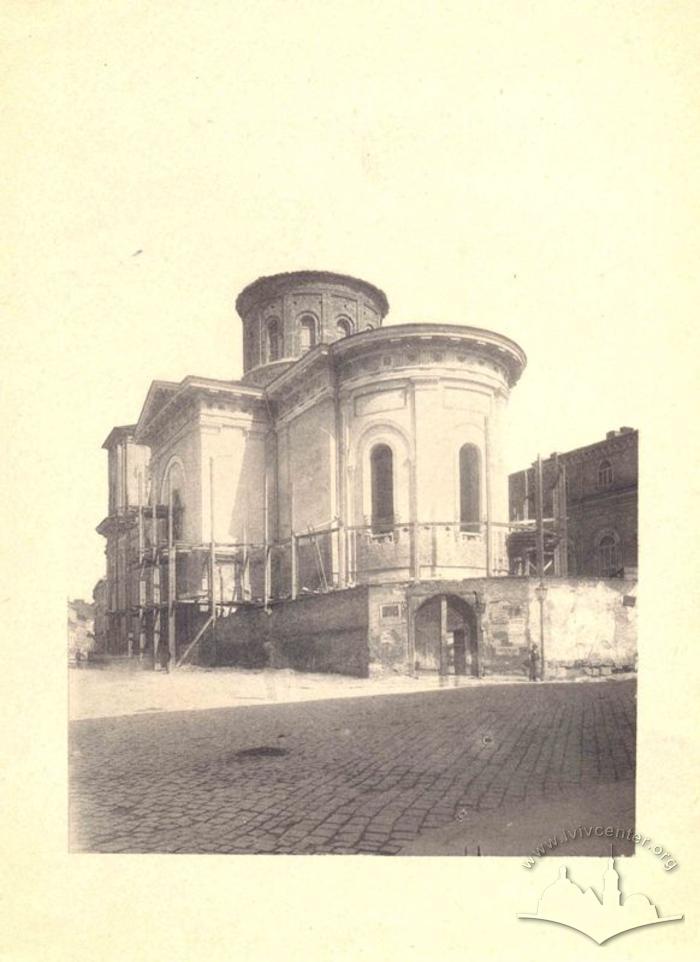

On May 31, the mass funeral of Ivan Franko was held, which was the largest event arranged by the Ukrainians in Lviv in 1916. On June 12-13, the consecration and opening of the Mykola Lysenko Musical Society building was also arranged. The building was interpreted as the main Ukrainian theater scene "in the capital of the province", while there was no Ukrainian theater, in contrast to the City Theater, which was actually Polish.

On July 7, 1916, Ukrainian students organized a prayer service at the grave of Adam Kocko: the student choir sang, and those present spoke about the symbolic role of his "sacrifice" in the conditions when the future of the nation was being decided.

With the return of the Austrian authorities, the traditional Polish patriotic "tours" were also resumed. On January 21-23, the anniversary of the January Uprising was celebrated. To participate in the solemn divine service "for the Polish cause" in the Latin Cathedral, the choir of the City Theater and students, specially exempted from studies for this purpose, were brought in. Solemn services were also held in the Armenian Cathedral and in the synagogue on ul. Żółkiewska. True, though, in the synagogue they officially prayed in memory of the rebels who died in 1863.

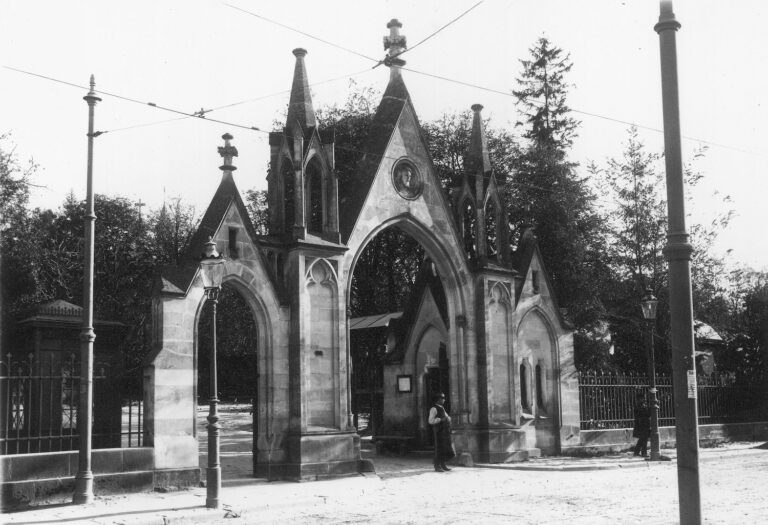

In general, like most events organized by the Ukrainians and Poles during the war, the celebrations dedicated to the January Uprising were aimed at charity. Money was collected during religious services, at a special evening performance by the City Theater and at a charity party at the Krakowski Hotel on the following day. The anniversary commemoration ended on January 23 at the Lychakiv cemetery near the graves of the participants of the January Uprising.

In 1916, despite slight opposition from the Austrian administration, the anniversary of the May 3 constitution was celebrated. There were solemn religious services and a performance in the City Theater; an honour guard of Polish legionnaires marched in front of the Latin Cathedral. Such a modest set of events contrasted sharply with the mass demonstration held in Warsaw. Not only the Ukrainian but also the Polish press wrote about the weak organization and weak involvement of the population, even in decorating houses.

Perhaps the point was not only "provinciality" or proximity to the frontline, but also the fact that new, more urgent reasons for mass mobilization had appeared. Those reasons had to do with "one's own army", that is, soldiers who served in the national units of the Austro-Hungarian army. Józef Piłsudski visited Lviv in March. His two-day stay was a whole "visit" with a program announced in newspapers, with a special poem as a greeting from "Lviv children." All this was reported in the press with no less pathos than the emperor's visit to the city.

On Friday, March 17, 1916, Józef Piłsudski visited the Lviv offices of the Polish Supreme National Committee and the Polish Women's League, a gathering (recruiting) point for legionnaires, a boarding school for children of legionnaires, a shelter for former legionnaires. In the evening, there was a charity performance at the City Theater, the funds from which were once again directed to the widows and orphans of legionnaires. On March 18, Piłsudski attended a charity reception in the City Casino organized by the Women's League. In effect, it looked like a working visit by a staff officer, but no Austrian imperial institution was involved.

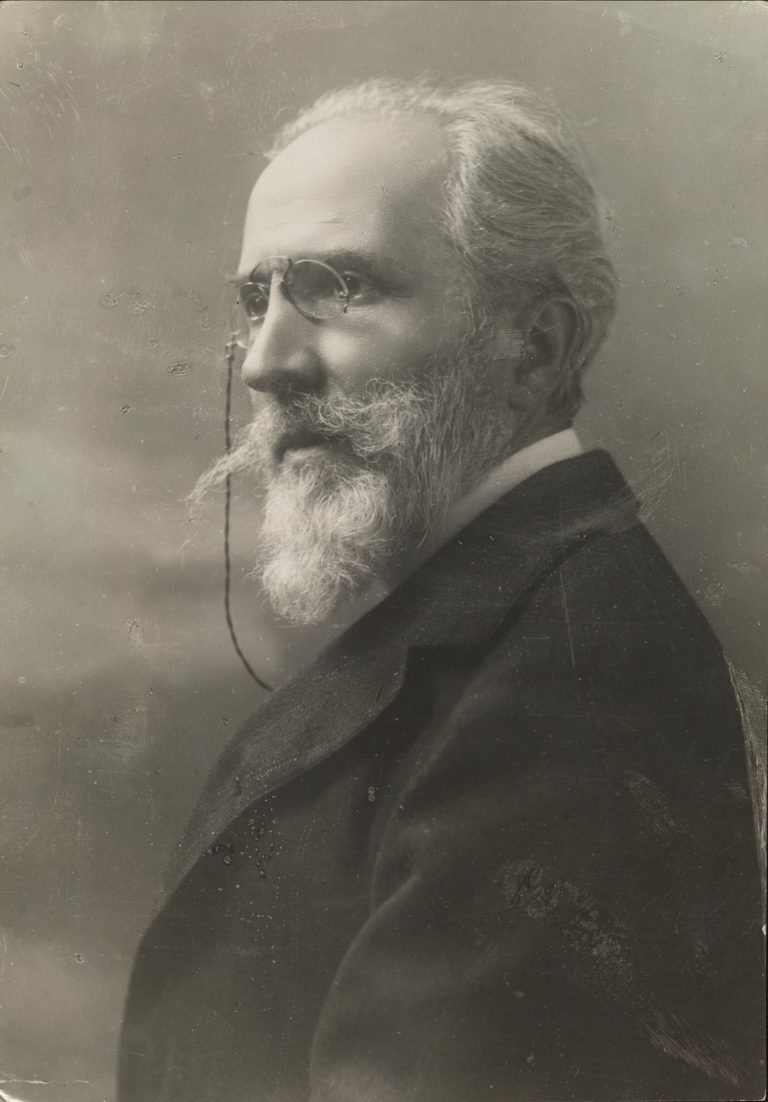

In May, Lviv was visited by the commander of the Legion of Ukrainian Sich Riflemen, Antin Varyvoda. The programme of the visit was more modest, but there also were meetings and a dinner; it all was described in Ukrainian newspapers as well.

- Юзеф Пілсудський / Józef Piłsudski

- Антін Варивода / Antin Varyvoda

Under the influence of the war, All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day (November 1-2) had a military and nationalist character, with mostly "one's own heroes" honoured at cemeteries.

On November 5, the German and Austrian command proclaimed the "free" Kingdom of Poland in the occupied territories of the Russian Empire, which not only caused mass celebrations in Lviv, but also started a new stage in Lviv's public politics. It was a stage when the matter of "Polish Lviv" seemed to be resolved and Ukrainian claims rejected; the only question now was how closely Galicia would "unite" with the Kingdom of Poland and in what status.

* * *

During the period from December 1915, when residents evacuated before the occupation were allowed to return to the city, and until November 1916, when the Austrians and Germans decided to declare the independence of the Polish state, hopes for a return to the old practices of "street politics" did not materialize.

It was clear that there would be no return to the old life as the Poles and Ukrainians were increasingly emphasizing their future statehood. Obviously, the Austrian authorities could not let such trends take their course, so they partially limited the activity of national politicians and also proposed their own agenda.

However, both the Ukrainians and Poles, still enjoying their freedom against the background of what happened during the Russian occupation, returned to the old patriotic calendar. They also supplemented it with new, more relevant and war-related dates and meanings, new heroes and "their own army."