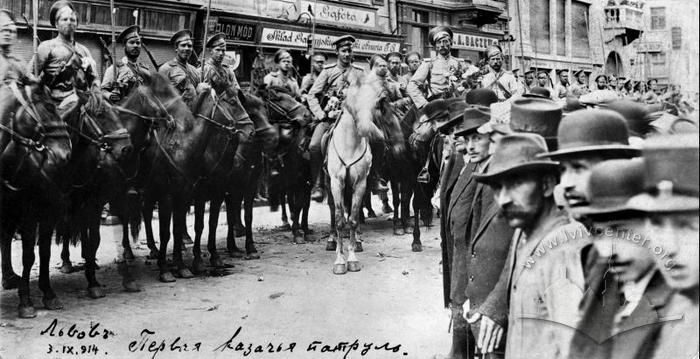

Despite the fact that the situation with food and heating in 1918 was very bad, this did not reduce the fervour of political activists in Lviv — especially in circumstances when, as the newspapers often reported, "the destiny of the future of nations was being decided."

Obviously, it was connected with tectonic political changes on the political map of Europe. The idea that after the end of the Great War Ukraine and Poland would be independent states naturally raised questions about the future of Lviv and Eastern Galicia, where the Ukrainians and Poles had long been competitors. The "winners" were not determined in advance, and no one planned to give up their "right to the ancestral land."

Labour strikes at the beginning of the year

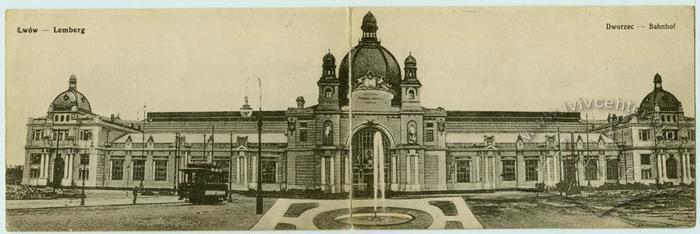

At the beginning of 1918, information about strikes began to appear in the press; in particular, strikes were planned at strategic objects like the railway. Since during the war all protests were severely curtailed, it showed that workers had found themselves in a really difficult situation. It also confirmed the fact that the influence of the revolution in Russia and/or the weakening of the central government was felt in Lviv.

During the workers' protests, national demands came to the fore. On January 21, Ukrainian railway workers in Lviv started a strike and spoke out against the hypothetical annexation of Chełm Land, Podlasie and Eastern Galicia to Poland. Two weeks later, they announced the creation of a trade union independent from the Poles. The government press, in particular the Gazeta Lwowska, did not mention the national demands, citing the difficult financial situation and low wages as the reason for the strike of 1,600 Lviv workers.

On February 18, as the manifestations caused by the Peace of Brest reached their height, Polish tram workers (who were on strike in January as well) gathered and decided to transfer one day's salary to help the Polish legions. Their Ukrainian colleagues were informed about it after the event. The Ukrainians were outraged by this charity on their behalf, since it was aimed at "enemy goals".

In the end, the labour movement in Lviv, which had been divided into Christian and Jewish parts, also divided into Ukrainian and Polish parts: Ukrainian postmen, railway workers, and officials began to announce the creation of their own national labour organizations.

Inter-party competition

In addition to workers' demonstrations, in early 1918 inter-party competition returned to Lviv — in its extreme, conflicting manifestations at once. On February 2, as some newspapers reported, a "convention of national labour" took place in the city: representatives of various economical sectors, as well as local politicians and even the provincial marshal, discussed the future of Eastern Galicia in the City Hall. In other newspapers, there was a talk of a "meeting of the newly formed right wing." Anyway, in the evening, when a banquet was going on in the hotel restaurant on ul. Batorego, about two thousand supporters of the "democratic youth" (sympathizers of the Polish right wing, the so-called endecja) came there to "express their protest." They broke the windows but did not manage to get inside, prevented by security and the police. As a result of the shootout between the police and the demonstrators, two young people were injured. According to one version, these were a gymnasium student and a student, according to another, two gymnasium students. One of them, Maryan Czerkas, died, while the other, Wodzicki, recovered. Eight demonstrators were arrested, seven police officers were injured. Later, rumours spread that the Polish students had been shot by German soldiers from the German field post building on ul. Batorego, but this version was soon denied. Who exactly fired, the demonstrators or the police, was never found out.

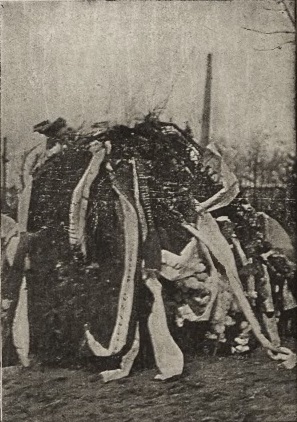

The funeral of Maryan Czerkas, as expected, turned into a demonstration that went from the Boim chapel to the Janowski cemetery. The Krakow magazine Nowości Illustrowane put the number of participants in the funeral at 100,000, but this is very unlikely. Instead, there is no doubt that the participants decorated their clothes and wreaths with white and red symbols, that the coffin was carried by gymnasium and university students, and that a railway band took part in the procession.

The Peace of Brest

It was in these atmosphere of conflict (also social) and international competition that information about the conclusion of peace in Brest appeared; these news caused the Ukrainians to triumph and the Poles to protest. The Brest Peace Agreement of February 9, 1918, according to which the Central Powers signed peace with the Ukrainian People's Republic (and therefore recognized Chełm Land and Pódlasie as Ukrainian), was called the "Fourth Partition of Poland" by the Polish press. Mourning flags were hung in Krakow, newspapers were published with empty columns in black frames, the question of the future of the Poles in Eastern Galicia and Lviv became acute.

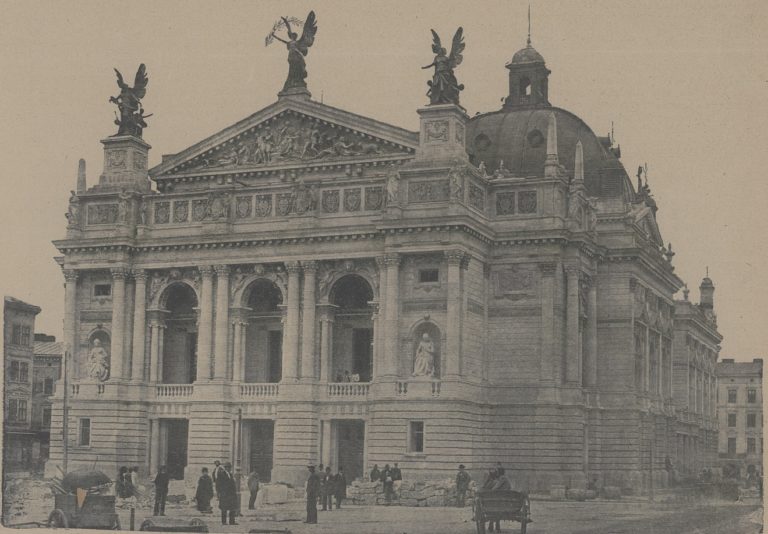

On February 12, 1918, Ukrainian organizations of the city of Lviv held a meeting for approximately 200 people in the hall of the Besida society. Due to the signing of the Brest Peace Treaty, the event program was changed: international news became the main topic. In this context, the destiny of Eastern Galicia and the representation of the Ukrainians in the Lviv City Council was discussed. In this situation, the Ukrainians were completely satisfied with the government's position, while Polish politicians began to appeal directly to the "people", calling the agreements in Brest "paper one" and urging people to take no heed of Vienna's or Berlin's position. On the same February 12, Polish politicians organized a "public meeting" in the city hall; after the meeting, the participants went to the City Theater and disrupted the performance (because it is not good to have fun in times of need). On the following day, again in the city hall, a meeting of "all political parties" was held to discuss the situation, as well as another three meetings, an "academic" one, a "public" one and that of the Sokoł society at which the "loss of lands and 4 million Poles" and the "German intrigue" were discussed.

The following days were dedicated to the general strike announced by the Poles for Monday, February 18. The Ukrainians discussed in the press how to counter it, calling on non-Polish officials not to be afraid of the replacement of the "Kaiser cap with a konfederatka cap", because it would not happen. They also stated that they did not rule out armed confrontation and had "their own military and self-defense." Polish meetings were held at the Strilnytsia, in the city hall's assembly room and courtyard, in various associations's premises. Officials, railway workers, various organizations held their own gatherings.

Polish protests against the Brest Peace

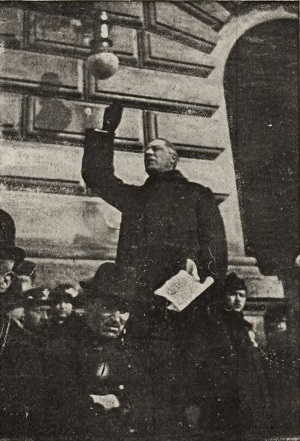

The strike on Monday, February 18 began with services in churches and synagogues at 9 a.m. People started to gather in the city center at 10 a.m.; an hour later people lined up for a march to the Sejm building. It was led by Polish scout paramilitary organizations while the civil guard helped keep order. On their way to the Sejm for the main meeting they stopped at platforms specially arranged along the streets, where speeches were delivered: a total of 36 speakers spoke. In particular, Tadeusz Rutowski, the president of the city of Lviv, Ludomir Benedyktowicz, a representative of the organization for the 1863 rebellion participants, as well as a student on behalf of the Polish students of Lviv spoke at the podium near the city hall. On the eve of the march, the organizers asked shop owners not to open on the day of the strike (Ukrainians interpreted this call as intimidation of "shopkeepers and profiteers"), so most of the establishments in the city center were closed. Restaurants and cafes were open only at lunchtime, tram workers and officials were on strike.

After the rally near the Sejm building, people dispersed to Polish and Jewish associations and held separate meetings and gatherings, where the Peace of Brest was also condemned.

A direct conflict between the Poles and Ukrainians occurred at the University, which was also on strike; the Ukrainian students, though, demanded that the rector conduct studies. Therefore, a fight happened not for the first time at the University between Ukrainian and Polish students who came specifically to "ensure a general strike."

After the Polish rally and strike on February 18, posters appeared on the streets of Lviv through which Polish politicians announced "mobilization." The Ukrainian press reacted with similar calls, describing the state of Ukrainian-Polish relations as "a war." Ukrainian appeals to the "people from the region" (that is, the peasants of Eastern Galicia) who could "oust a handful of Polish administrators" rang out again. This became all the more relevant after the Polish strike, which allegedly demonstrated the "powerlessness of the Austrian state" and the collapse of the Austrian policy of "renting the province out to the Poles."

Another type of posters and booklets that appeared in late February was anti-Jewish. These directly called for pogroms and "cleansing Poland of Jews." Several distributors of such propaganda were arrested by the police; then it was announced in the press that the provocative propaganda leaflets had been printed abroad.

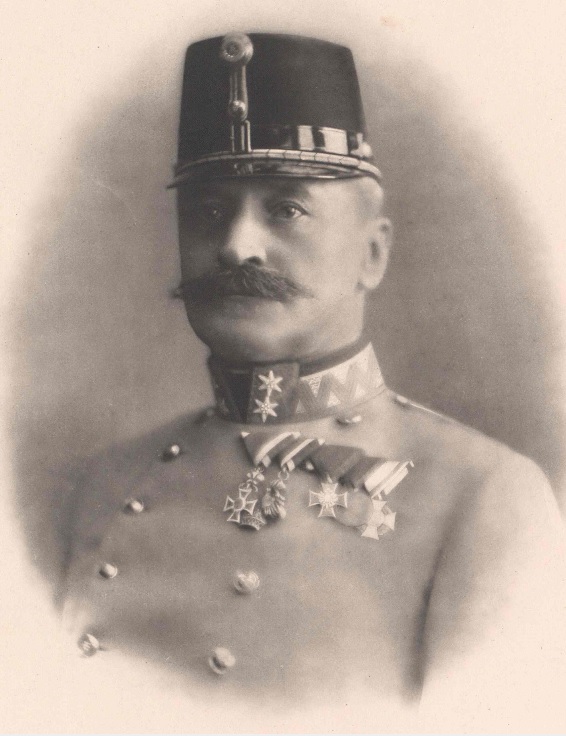

In general, there was nothing special in the fact that the Poles and Ukrainians assessed the strike differently. This happened all the time, but earlier it was possible to keep everything within some limits and not to oppose Vienna. This time, the presence of the Polish Civil Guard (as it had always been) was interpreted by the Ukrainians as a paralysis of the government, they demanded the resignation of Governor Karl von Huyn, and the action itself was called anti-Austrian, anti-German and anti-Ukrainian. After the proclamation of the Peace of Brest, Lviv and Krakow, according to Ukrainian politicians, looked like cities where the revolution won and not as cities loyal to the empire.

The position of Polish politicians cannot really be called loyal to Vienna, indeed. Controlling Lviv, they could not do anything on an international scale. Therefore, for them it remained, for example, not to publish the manifesto of Emperor Charles "To my peoples" in newspapers or to publish posters with the manifesto, but only in late February and only in German and Ukrainian, without a Polish version. What’s more, just the day before, the City Council resumed its work and conflicts immediately broke out over the use of the Ukrainian language there.

The situation was similar in the province. The Ukrainians organized meetings and demonstrations in honour of the Ukrainian statehood in county centers, relying on the rural population. The Poles held their rallies in cities and towns.

Great Ukrainian manifestation

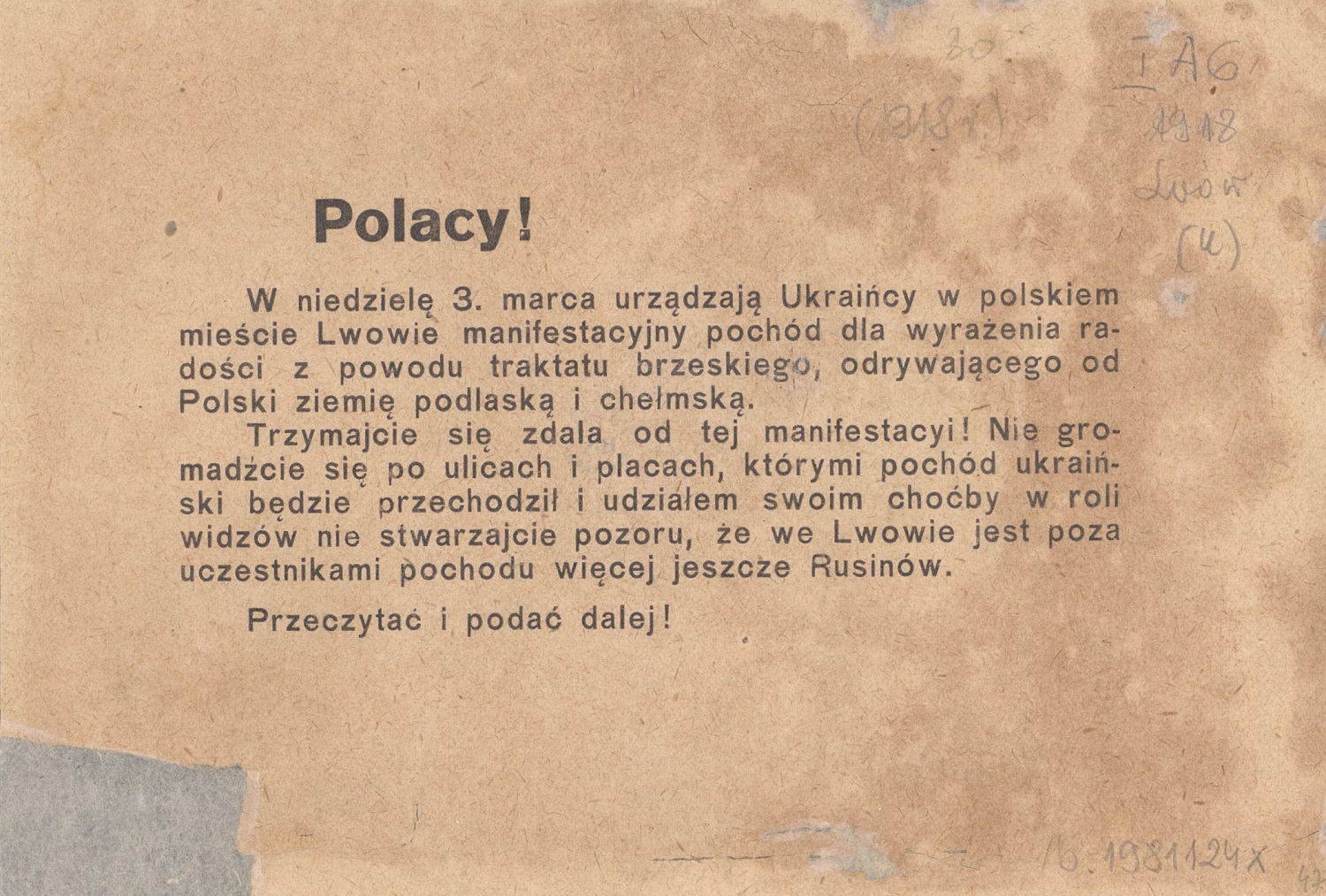

Before the Fourth Universal and the declaration of independence of the Ukrainian People's Republic in January 1918, Dnieper Ukraine was considered part of the hostile Russian Empire; therefore, in the previous months, loyal subjects of Austria could not hold public demonstrations in honour of the Ukrainian autonomy or statehood on the banks of the Dnieper. Ukrainian politicians had been planning the demonstration to be held in early March 1918 since January: it was imagined as a "holiday of the Ukrainian People's Republic" then. However, the signing of the Peace of Brest and the reaction of the Poles to it changed the situation. So, starting from February 18, the Ukrainian press announced the "holiday of peace and Ukrainian statehood" for March 3, 1918.

The plan was to hold mass demonstrations in all county centers of Eastern Galicia on one day and to update the main political issues relevant for the Ukrainians at that time: the peace of the Central Powers with the Ukrainian People's Republic, the recognition of Chełm Land and Podlasie as Ukrainian territories, the fate of the probable "Ukrainian Kingdom of Galicia" as part of the Habsburg Monarchy (that is, the division of Galicia into Eastern Ukrainian and Western Polish parts). The organizers paid special attention not to the mass nature of the events, as usual, but to the formation of the civil guard, "ready at any call" to repel possible provocations from the Poles. After all, it was not only a question of mobilizing "one’s own people", but also a question of scaring the "strangers." The newspaper Dilo reported without unnecessary hints that "the Polish islands in the Ukrainian sea, which dare to deny the Ukrainian people the right to own this land, would see the will and strength of the Ukrainian people."

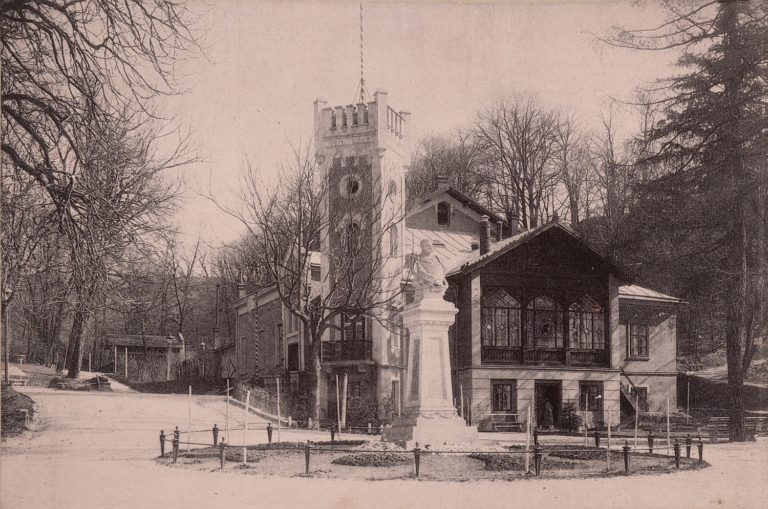

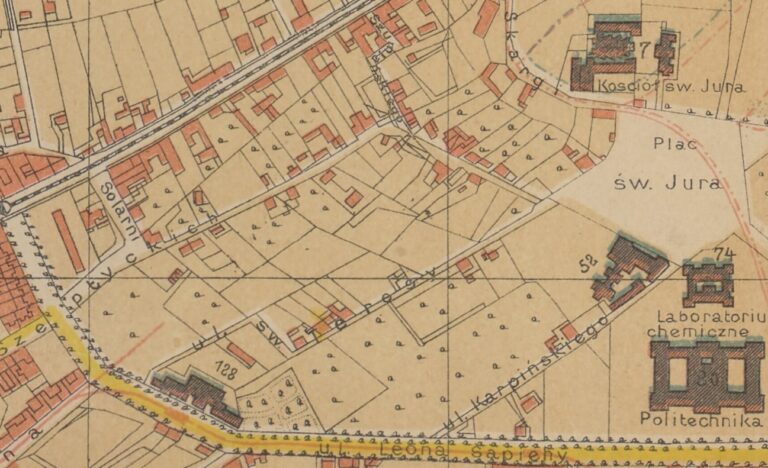

The participants planned to gather on pl. Sv. Yura. They were asked to come in advance, preferably with national symbols. For those residents of the Lviv county who could not come in the morning, an overnight stay was organized in the hall of the Ukrainian Sokil III society and in the Borys Hrinchenko school (at ul. Grodecka 45 and 95, now numbers 85 and X, respectively).

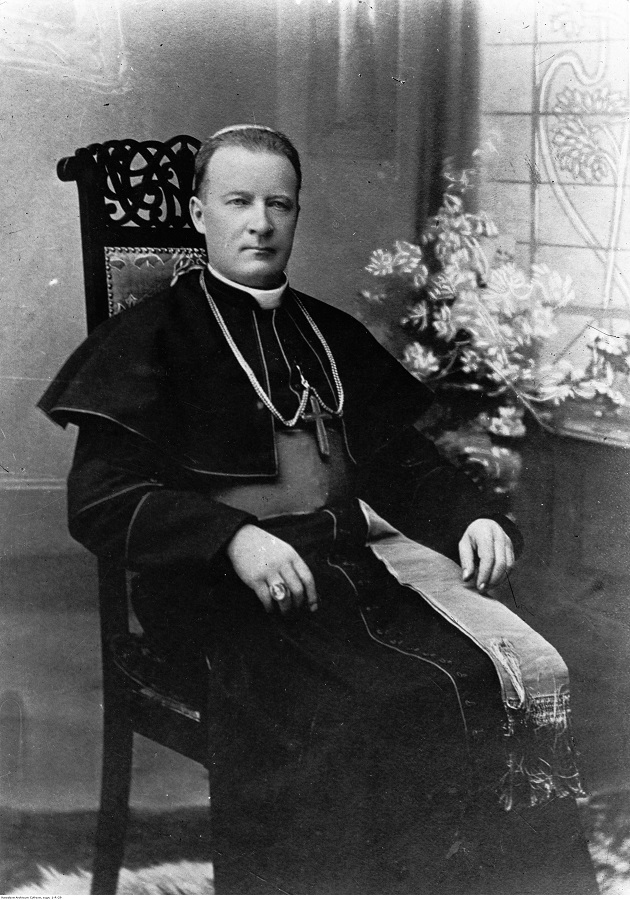

The divine service in St. George's Cathedral, actually as part of the manifestation, started at 9 a.m., in other Greek Catholic churches of the Lviv county earlier, so that the participants could get to the gathering place. The service was led by Metropolitan Andrey Sheptytskyi, who delivered a patriotic sermon.

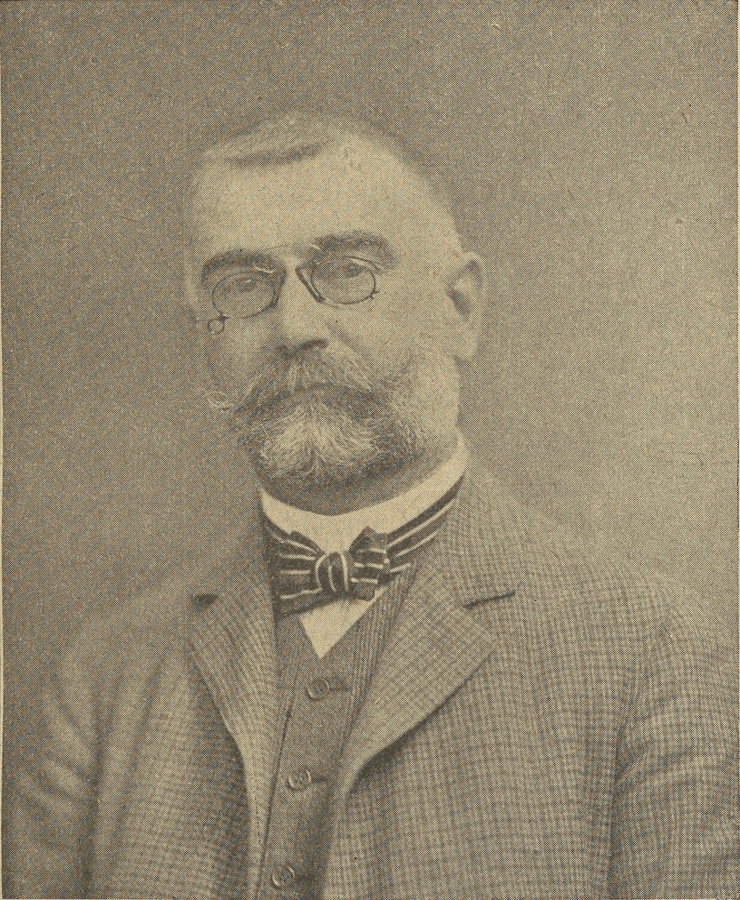

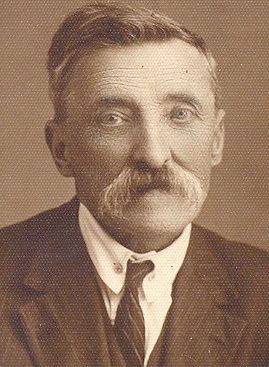

At 11 a.m., the rally began; actually, there were three speeches in different places of the square. The editor of the newspaper Dilo Mykhailo Lozynskyi spoke in front of the St. George's Cathedral's gate to Lviv residents, representatives of Ukrainian associations of Lviv, clergy, and Sich riflemen, who gathered there. From the "terrace of the metropolitan's house" on ul. Mickiewicza (probably where the Novakivskyi Museum is located nowadays), Lonhyn Tsehelskyi, a member of parliament, spoke to villagers, railway and post office workers. The third speech, from the side of ul. St. Therese (now vul. Mytropolyta Andreya), was delivered to the youth by trade unionist Oleksandr Pisetskyi.

After all the speeches, the orchestra of Ukrainian railway workers performed the national anthem, and at 11:45 a.m. the march to the city center began. The participants moved in the following order:

- members of the Sokil society in uniforms, female members of physical culture societies (so-called "rukhovychky"), the railwaymen's orchestra, members of the newly formed Ukrainian railwaymen's society with a flag, Plast scouts (also with a flag);

- schoolchildren from Ukrainian schools with blue-and-yellow flags, gymnasium students, university and Polytechnic students, and seminarians;

- around 80 horsemen from the nearby villages, peasants who carried signs with the names of their villages, a group of former POWs (Ukrainian soldiers of the Russian army), members of the Ukrainian societies from the suburbs (Levandivka, Bohdanivka, Klepariv, etc.) with the corresponding signs, members of Lviv labour and craft organizations. Still, the majority of this peasant group consisted of women (with songbooks);

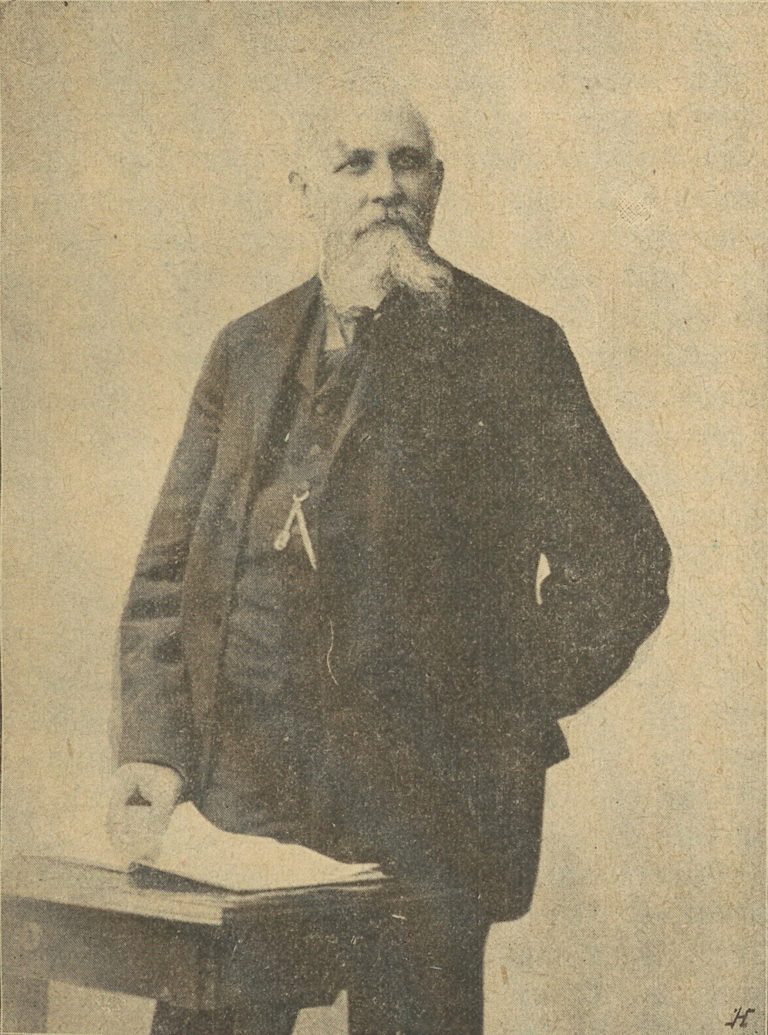

- officials, postal workers, representatives of cultural and economic societies, intelligentsia, Ukrainian officers of the Austrian army, members of parliament led by Yulian Romanchuk, Greek Catholic clergy;

- Sich riflemen, who formed the rear guard of the march.

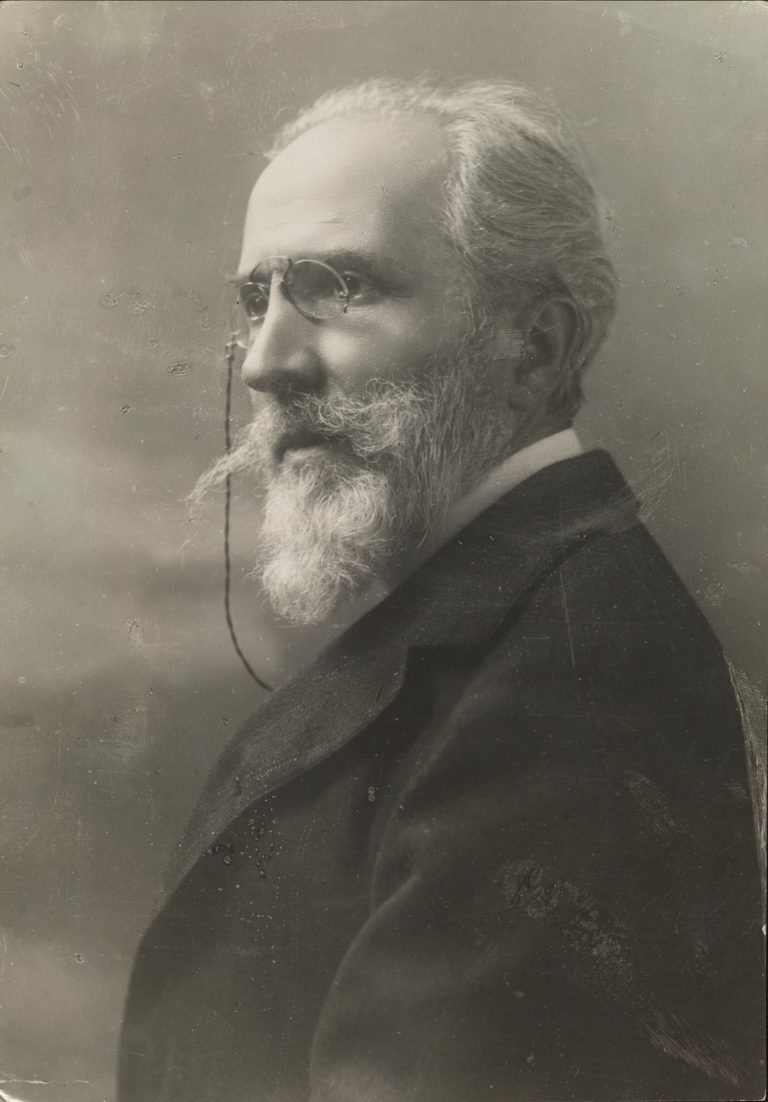

Apart from flags, the participants carried numerous banners with, actually, only two slogans, showing their support for the Ukrainian People's Republic and for "Ukrainian statehood in Austria." On pl. Rynok, member of parliament Kost Levytskyi spoke from the Prosvita building balcony, welcoming the peace treaty, rejoicing at the entry of the Allies into Kyiv, and not forgetting to mention Chełm Land and Podlasie, which "Poland wanted to conquer." He ended his speech with a call to stop "Polish oppression in Galicia due to the formation of a Ukrainian state unit." Besides, those present spoke about the union of Ukraine and Austria and about the role of "one's own" army in the future state. The rally ended with the performance of the Ukrainian national anthem.

In general, Ukrainian newspapers reported on 60,000 participants (which is unlikely), mostly peasant women. However, the massiveness of the event is evidenced by the fact that the column stretched from pl. Sv. Yura to pl. Rynok; when the rally continued there, the participants occupied the entire square. The tram traffic was stopped at that time.

As always, there were conflicts with the Poles. The Dilo reported that gendarmes had detained some villagers travelling to Lviv for the demonstration and that transport conductors also tried to create obstacles. Provocations by Polish youth and Polish teachers were reported on as well. During the march itself on ul. Mickiewicza, some local residents even threw garbage out of the windows on the heads of the demonstrators. One way or another, the manifestation was considered successful by Ukrainian politicians, as were similar events on March 3 in all county centers of Eastern Galicia. In the end, the reaction of the Polish nationalists was indeed very restrained as there were no significant provocations or attempts at use of force. Perhaps this was due to the restrictions of martial law and the fact that Polish nationalists did not dare to fight in the streets against both the Ukrainians and the authorities at the same time.

Attempts at returning to "normal life"

Obviously, against the background of such tectonic shifts in national politics, other obligatory calendar events had faded into the shadows. Like, for example, May 1, when the Ukrainians ("comrades", as the press reported) gathered in the People's House and talked mainly about national problems and not about the solidarity of workers all over the world.

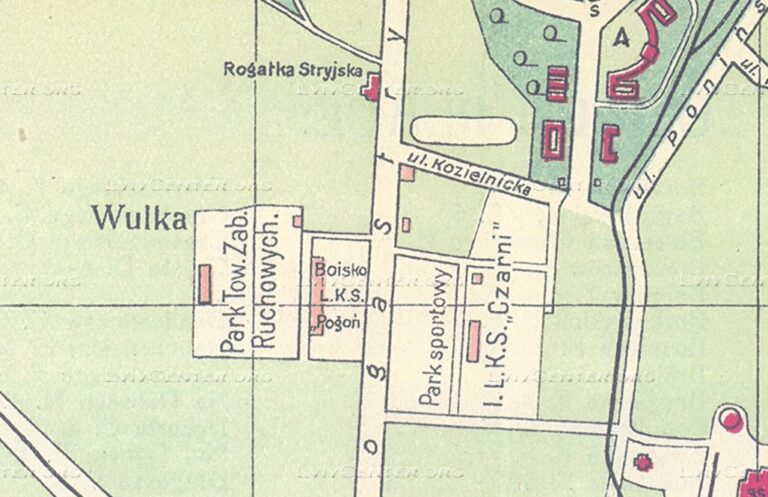

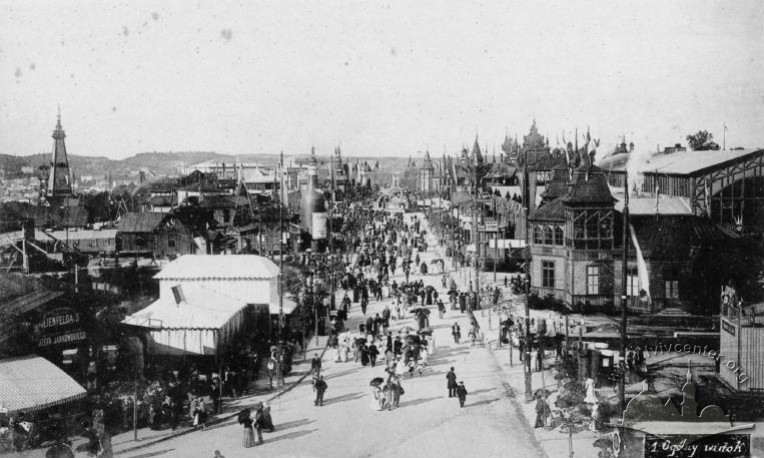

Attempts by the Austrians to return street politics to the direction of loyalty to the empire also looked weak and uncompetitive. In late May and early June, the "Emperor and King Charles Week" was announced in Lviv. It was a series of events to collect charitable donations for widows, orphans and invalids of war: something like the "Iron Knight", but stretched in time and space. Every evening from Wednesday, May 29 to Friday, June 7, Lviv residents were offered some kind of entertainment: performances in theaters, sports entertainment at the Pogon stadium, concerts of military bands, feasts on the post-exhibition square, special programs for exhibitions and cinemas. There were no excesses, but the massive nature typical for similar events after the liberation of Lviv from the Russians was not reached.

In addition, the economic troubles caused by the January railway strikes had not gone away. On June 7, a mob consisting mainly of women, children, and teenagers looted several shops in the city center; near the City Theater, people looted a grocery store belonging to the magistrate. Several people were injured with stones, shops were hastily closed, the police managed to restore order a few hours later. On June 8, there was unrest at the magistrate as people demanded cheaper foodstuffs.

The collapse of Ukrainian illusions in the autumn of 1918

The hopes of Ukrainians for government help, born after the Peace of Brest signed on February 9, 1918, were dashed as soon as the autumn of the same year, when in Vienna there was a government crisis and a change of cabinet, which ended with the rejection of the Peace of Brest policy. To remind the government of their demand for the division of Galicia, Ukrainian politicians decided to repeat a series of "national manifestations" in county centers, as was the case on March 3. They wanted to hold demonstrations during the “manifestation week” of September 15-22, but it was possible not everywhere and not as massively as in the spring. The situation changed clearly not in favour of the Ukrainians; the organizers, however, traditionally blamed only Polish officials for the failure of the action.

The Lviv city manifestation on Sunday, September 22 was actually held in the People's House, not on the square. A qualitative change was that this time the speakers (Kost Levytskyi, Stepan Baran, Modest Levytskyi from Kyiv, Lonhyn Tsehelskyi) clearly articulated the idea of unification with Kyiv, as hopes for the Austrians seemed to have dissipated. On Tuesday, September 24, again in the hall, now that of the Mykola Lysenko Music Society, a county rally took place. It differed from the meeting two days before by a significant number of peasant women and parish priests, who led delegations from the nearby villages.

Meanwhile, Polish politicians in Lviv, on the contrary, felt a surge of enthusiasm, especially after the decision of the Regency Council in Warsaw to declare Poland's independence taken in early October. They quickly organized various meetings at organizations and societies, held meetings in the city hall and an impromptu rally in the City Theater instead of the planned performance. Welcoming 80 legionnaires who were returning home from the frontline turned into a manifestation with a crowd at the railway station, a reception at the residence of Archbishop Józef Bilczewski, celebrations in coffee shops, a march to the city center and a ceremonial assembly in the city hall.

Emperor Charles I's manifesto of October 16, 1918 on the transformation of Austria-Hungary into a federation was met by the Ukrainians and Poles with a clear desire to expel each other from "their legitimate lands."

* * *

The year 1918 showed that the Ukrainians could, in the case of full loyalty on the part of the authorities, mobilize thousands of supporters on the streets of Lviv. At the same time, however, it showed that the Poles were ready to resist, reaching as far as involving public officials in strikes during the war. The main thing, though, was that material difficulties, shortages or poverty were not an obstacle for political activity.